Excerpt

Excerpt

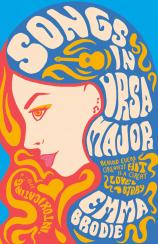

Songs in Ursa Major

1

Island Folk Fest

Saturday, July 26, 1969

As a stagehand cleared the dismantled pieces of Flower Moon’s drum set, the last shred of daylight formed a golden curve around the cymbal. It winked at the crowd; then the red sun slipped into the sea. In the gathering dusk, the platform shimmered like an enamel shell, reverberating with the audience’s anticipation.

Any minute now, Jesse Reid would go on.

Curtis Wilks stood about thirty feet from the platform with the rest of the press. There was Billboard’s Zeke Felton, sharing a joint with a Flower Moon groupie in a beaded kaftan; Ted Munz from NME, reading over his notes under the nearest floodlight; Lee Harmon of Creem, trading stories with Time’s Jim Faust.

The Flower Moon groupie approached Curtis with the joint between her lips, eyeing the pass around his neck. It showed a picture of Curtis’s face—which Keith Moon had once compared to “a homeless man’s Paddington Bear”—printed above his name and the words Rolling Stone. The groupie offered Curtis the joint. He accepted it.

His exhale became a brushstroke inside an Impressionist painting; swirls of smoke rose in the salty air, tanned limbs and youthful faces interweaving like daisy chains across the meadow. He handed the joint back to the girl and watched her skip into a ring of hippies. Someone had a conga; thrift-store nymphs began dancing to an asynchronous rhythm.

Curtis had cut his teeth as a correspondent on the festival circuit. Berkeley, Philly, Big Sur, Newport—none of them could touch Bayleen Island for atmosphere: the hike up the red clay cliffs, the wildflower meadow, the view of the Atlantic Ocean. There was something magical about having to take a ferry to get to a show.

As he watched the girls dance, Curtis felt a wave of premature nostalgia. There was a sense in the industry that folk was on its way out; the Vietnam War had been dragging on so long, the protest songs that had made Dylan and Baez what they were now felt empty and tired.

Curtis had come to see what they’d all come to see: Jesse Reid ushering in a new epoch for the dying genre. As if on cue, the dancing girls began to sing Reid’s breakout single, their voices tremulous with excitement.

“My girl’s got beads of red and yellow,

Her eyes are starry bright.”

Their feverish giggles recalled Curtis to the time a young Elvis Presley had played his high school in Gladewater, Texas, back in ’55. Eighteen-year-old Buddy Holly–obsessed Curtis had watched girls he’d known since kindergarten openly weep, swept away by the fantasy that Elvis might choose them. The full Bye Bye Birdie. That was the power of a true rock star.

Soft-spoken Jesse Reid’s persona couldn’t have been more different from Elvis’s, but Reid seemed to inspire the same devotion in his fans. He had the cowboy baritone of Kris Kristofferson (but Reid’s sounded effortless), and the lyrical guitar skills of Paul Simon—plus, he was taller than both, with blue eyes that, according to Curtis’s guilty pleasure Snitch Magazine, were “the color of medium stonewash Levi’s.”

“She makes me feel so sweet and mellow,

She makes me feel all right.”

“Sweet and Mellow” was a Snickers bar of a song; to hear it was to crave it. Hands down the hit of the summer, it had been holding in Billboard’s top ten for eighteen weeks. Curtis had been tracking Reid since he opened for Fair Play at Wembley Stadium the previous year—but this single from Reid’s self-titled album had turned him from fringe hero to mainstream sensation overnight.

And tonight, Reid would take his place as the heir apparent to folk rock.

The crowd broke into applause as a bald man with a gray beard shuffled onstage—Joe Maynard, the Festival Committee chair. The longer the audience clapped, the more pained Maynard looked. Curtis’s news radar bristled.

“Yes, hello, my beautiful friends,” he said. Maynard quieted the cheering with his hands.

“Well, there’s no easy way to say this, so I’m just going to say it,” he said. “I’m afraid Jesse Reid won’t be performing tonight.”

Curtis felt a stab of disappointment as his mental list of feature headlines turned to ash. A visceral shock wave passed through the crowd. One by one, dreamy expressions began to wilt, a field of dandelions turning white with anger, ready to blow.

And then they did. Cries of outrage rang the twilight like a bell. The girls who had been singing and dancing a moment before collapsed into sobs. Maynard shrank behind the mic.

“But we’ve got a great act for you up next—it’ll just be a few minutes now,” he said, sweat gleaming at his temples. A second roar from the crowd buffeted him into the wings.

Curtis edged toward the platform. Something must have just happened—he’d seen Reid’s A&R man backstage after Curtis had interviewed Flower Moon. Maybe Reid had gotten too drunk to go on. Maybe he’d lost it backstage. The festival tonight was performance number thirty-six in a sixty-arena global tour. Sometimes artists just cracked; Curtis had seen it before.

He spied Mark Edison passing from the backstage area into the audience and caught his eye. Edison was a reporter for The Island Gazette, a local independent daily. Most of the Fest’s press corps found his snide antics insufferable, but he had always been useful to Curtis.

The audience’s initial dismay had given way to movement. Amidst cries from the most stalwart Reid fanatics, lines had begun to form through the crowd, pushing toward the exits.

Edison reached Curtis. He offered Curtis his flask—warm gin. They both drank deeply.

“What’s happening back there?” said Curtis. “Where’s Reid?”

Edison shook his head. They stepped aside as two girls thundered by, ripping up the peace love jesse sign they carried like a banner. Curtis did not envy the band about to perform to this mob.

“Who’s going on?” said Curtis. “Someone from tomorrow’s lineup?” Mark shook his head.

“It’s a local band—the Breakers,” said Mark.

“I don’t know them,” said Curtis. “What’s their label?”

“Label?” said Mark. “They don’t have one. They’re just a bunch of kids. They were scheduled to play at the amateur stage down the hill, and the committee just scooped them up. The biggest show they’ve ever played is forty, fifty people.”

“Holy shit,” said Curtis. This was going to be a train wreck.

As he spoke, three young men began to set up onstage. They couldn’t have been more than twenty. The drummer looked the most filled out, with a chiseled jaw, shoulder-length black hair, and almond-toned skin. He and the bassist were clearly related; the bassist looked younger, hair shorn around his chin, a red bandanna tied across his brow. The guitarist was paler, with boyish features and a somber manner. His sandy hair flopped in front of his eyes as he tuned.

“We want Jesse!” a girl shrieked from over Curtis’s shoulder.

Curtis began to wonder if it wasn’t better just to head back to town. The Elektra producers had rented a yacht and were hosting an after-party for industry folk. Bayleen Island was only five miles from international waters, which meant good drugs; he could be flying within the hour.

“Jesse Reid, Jesse Reid,” a chant rose up in the crowd among the faithful.

As the boys checked their equipment, Curtis noticed a figure plugging in to the amplifier behind the drum set. As she straightened up, the spotlight caught her yellow hair, which hung down to her waist in a bolt of golden silk. Her clothing was simple: jean cutoffs and a white peasant shirt, an acoustic guitar strapped across her back. Her tanned legs looked girlish as she strode center stage, but she had a woman’s features: full lips, hollow cheekbones.

She glowed.

“Who is that?” said Curtis.

“Jane Quinn,” said Mark. “Lead vocals and guitar.”

As she got into position, the boys instinctively inched toward her. Their feet pawed the ground, like horses anxious at the starting gate.

“We want Jesse!” a hysterical girl cried out.

Jane Quinn stepped up to the mic. Curtis saw then that her feet were bare.

“Wow,” she said, flushed with excitement. “Quite a view from up here.”

The crowd ignored her. Those headed toward the exits continued walking, as if she wasn’t there. A small contingent of Reid fans chanted his name like a descant over the din.

“Jesse Reid, Jesse Reid.”

Jane Quinn tried again.

“Hi, everyone,” said Jane. “We’re the Breakers.”

This had no impact; the crowd continued to chatter as though they were in a parking lot rather than at a concert. Onstage, the boys fidgeted in place. Jane exchanged a look with the guitarist.

“Get off the stage,” a shrill voice cried above the chaos.

Jane glanced toward the drummer as though about to count off. She faltered. Curtis felt a wave of pity. How was this slip of a girl supposed to compete with one of the world’s biggest stars?

“Jesse Reid, Jesse Reid.”

Then Jane Quinn turned toward the crowd, squaring her shoulders. Her movements were slow and deliberate. She took a deep breath and placed a hand on the mic stand, closing her eyes. She stood perfectly still, listening. The crowd quieted half a decibel.

When she opened her eyes, there was flint in her stare. She leaned toward the mic.

“My girl’s got beads of red and yellow.”

Curtis’s heart skipped a beat as the chorus from “Sweet and Mellow” arched over the meadow like a silver comet. Jane’s bandmates exchanged mystified looks. The crowd gasped.

Had she really just done that?

“Her eyes are starry bright.”

Jane Quinn surveyed the audience with self-assurance, as though to say, I know you think you want Jesse Reid, but I’m about to show you something so much better. It was like watching someone hold a lighter up to a monsoon. The girl was bold as fuck.

“She makes me feel so sweet and mellow.”

What a range—a soprano, in the school of Joan Baez and Judy Collins, though not nearly as patrician-sounding as Collins, or as embattled as Baez. There was an untrained edge in her voice, an almost Appalachian coarseness, that raised the hair on Curtis’s neck. Just gorgeous.

“She makes me feel all right.”

Jane glanced at her guitarist. He gave her a nod—she had taken a leap, and they were right behind her. The root chords of the song were a simple A-major progression any practiced group could pick up. The drummer counted them in, and the Breakers began to play.

Time slowed.

“My girl makes every day a hello.”

When Jesse Reid sang “Sweet and Mellow,” his voice intoned the melody: no ornamentation, just his pure baritone and his guitar. As Jane Quinn sang, she cast off any memory of Reid’s rendition, adding runs and grace notes as she went, as though composing the song in real time. Curtis was astounded. She made choices no other musician would have—or could have—made.

“Her eyes light up the night.”

The crowd couldn’t help themselves—they began to sing along. They had all come to witness a legend being born, and now they were: it just wasn’t Jesse Reid.

“She makes me feel so sweet and mellow.”

Curtis had been at Newport when Bob Dylan had walked onstage with his electric Fender Stratocaster. He’d been in Monterey two years later when Jimi Hendrix had lit his guitar on fire during “Wild Thing.” Neither compared to this. An unknown taking over the headlining spot—a girl. They’d be talking about Island Folk Fest ’69 forever.

“She makes me feel all right.”

Those who had been walking away turned back. Those who had been crying smiled. They whooped and cheered and kissed and hugged. When the song finished, they lost their minds.

“Janie Q!” shouted Edison, applauding beside Curtis.

Janie Q.

“It really is a beautiful night,” said Jane, as though continuing a conversation from earlier.

With that, she counted the Breakers into their next song—an up-tempo original called “Indigo” that brought to mind “White Rabbit.” Curtis couldn’t catch the words, but the music was hot. The Breakers had a great sound—a mix of art and psychedelic rock, all twisting notes and braying chords.

Even so, Jane’s voice stole the show. Her loveliness felt personal—it was impossible to look at her and not take flight in some small part of you. As she sang, Curtis felt that true rock-star feeling—he wanted her to see him. She gave her shoulders a small shimmy, light refracting off the silken strands of her hair. Then it happened. Jane Quinn grinned right at him. He just knew it.

Songs in Ursa Major

- Genres: Fiction, Women's Fiction

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Vintage

- ISBN-10: 0593312376

- ISBN-13: 9780593312377