Excerpt

Excerpt

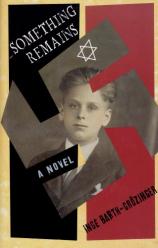

Something Remains

January 1933

The boy opened the small window and leaned out, kneeling on the narrow sill. He drew in deep breaths of cold air. It smelled of the smoke rising thinly from the chimneys of the houses opposite. Above the dirty gray rooftops he saw dark piles of cloud, blown apart now and then by strong gusts of wind. The pale disk of the sun would show as it gradually sank below the irregular zigzag of the roofs. The boy watched the drifting clouds for a while, and when the milky gray sun had finally sunk behind the buildings he sat down, sighing and lost in thought, with his back to the sloping wall as he massaged his aching knees. He felt safe in the dark, low-ceilinged attic room, and the rage that had driven him up here died down, giving way to a vague, muted melancholy. The Sabbath was over now. The boy's thoughts went down to the Levi family's living room. His mother would just have extinguished the candles in the silver candlesticks and put them carefully back in the cupboard inherited from Grandfather Elias, while Fanny cleared away the china. And Father would be sitting in the big, brown leather armchair with a cigarillo in his hand. As a cattle dealer, Julius Levi had to work even on the Sabbath, but he didn't allow himself to read the Saturday paper until evening when the sun had set and Sabbath was over, just as he waited until then to smoke one of the cigarillos he enjoyed so much. Later they'd switch on the radio, and amidst the usual affectionate teasing, the family would argue about which program to listen to. Father preferred light entertainment and Mother liked opera, for instance the works of Richard Wagner, though the rest of the family couldn't stand his music.

So everything was the same as usual, yet there was something different about this Saturday. And he had fled from whatever that "something different" was, running up to the dusty attic because he just couldn't take it in, couldn't understand it, and because it had been hanging over his family like an invisible veil for many days now, subtly changing them. For some time his mother hadn't laughed as often as usual, and his father's mischievous face suddenly looked gaunt, with two deep lines running down from the corners of his mouth.

The boy knew that it was something to do with the newspaper reports. The same names on the front page, in big fat type, had been leaping to the eye again and again these last few days. Those names were back today, and although he had been carefully avoiding the Saturday edition that lay on the chest of drawers in the corridor, the black characters held a magical fascination for him. They said hindenburg, they said schleicher, and over and over again they said hitler. The boy couldn't make much of these names. He did know that Hindenburg was the president of Germany, whose picture hung on the wall at school and in people's offices. He looked kindly, an easygoing old grandpa with a white sea-dog's beard. Schleicher was chancellor of the German Reich, his father had told him. And he'd heard that man Hitler on the radio several times, but only briefly, because when he came on, Father was always quick to switch the set off and silence his screeching, crackling voice.

From where he sat, the boy could see only a small section of the evening sky now. The outlines of the buildings had merged into the darkness. The boy listened. He could hear the clatter of china downstairs; Fanny had begun washing the dishes. Occasional voices, distorted as the wind carried them up and through the attic window, rose from passersby, probably on their way to the Red Ox on the other side of the street for an early evening drink. Only now did the boy notice the keen cold, and he rose and made his way carefully through the attic, which was entirely dark now, to the steep stairs. Down below he heard Mother calling, "Erich!" and then again, more urgently, "Erich, where are you?"

He let a few moments pass before he answered, rather gruffly, "Coming." He wasn't really melancholy after all; he was angry. In fact, furiously angry. Angry with those men. Their names told you nothing about them, but they were the reason for the strange atmosphere these days. Most of all that Hitler. For some reason he didn't understand, his parents seemed to be afraid of Hitler. That made him angry with his parents too. What did all this fuss in Berlin have to do with their family? What did a well-respected man like his father have to fear? Everyone in town raised their hats to him. As for Mother, there was hardly another woman in Ellwangen as pretty as Melanie Levi or as elegantly dressed. Many women were envious --- you could see from the way they looked at her --- and the men bowed a little more deeply than usual when they met Frau Levi in the street. Erich was proud of his parents, and he simply couldn't understand what had changed them so much.

So he made a sulky face when Mother said, sounding a little reproachful, "Where have you been, Erich? I thought we agreed that you and Max were going to help Fanny this evening. You know she has the evening off when she's done the dishes, and she wants to go dancing." She gave him an affectionate tap on the nose and gently stroked his hair. "Goodness, you're cold. And just look at your trousers, all dusty! Wherever have you been? Go on, find Max and off to the kitchen with you."

Max, two years younger than Erich, was lying on his stomach on his bed in their room, reading an adventure story by Karl May. Erich tiptoed up to him, and then suddenly snatched the book away. He studied the title, Through the Wilds of Kurdistan, and with his left hand fended off Max, who was trying to punch him in the ribs and retrieve his book. Finally Erich gave Max a push that sent him tumbling back on the bed. "Come on, we're off to the kitchen to do the dishes!"

Max turned to face the wall. "Don't want to."

Erich opened the wardrobe, found a clothes brush, and went over his trousers with it. Fanny had once told him he was the vainest boy she knew. With a glance at Max, lying there unmoved, he set off for the kitchen himself, sighing. "Was I as idiotic as that when I was ten?"

Fanny, standing at the sink, laughed when Erich posed the same question to her moments later. "Much worse! Do you remember how you wanted to marry me then?"

That made Erich laugh too, for the first time today. He went solemnly up to Fanny and looked her in the eye. "What do you mean, wanted? My heart still beats for you alone!"

Fanny's hand emerged from the soapsuds, and she ran her fingers through his hair until it stood out in all directions, wet and gleaming. "Erich Levi, I swear you're the most impossible boy in the whole world! Oh, the hearts you'll break some day with those big brown eyes of yours! Eyes like a dachshund's, they are! Don't look at me like that, you Casanova --- the tea cloth's over there."

They worked in silence for a while, and then Fanny nodded toward the living room door. Father's voice could be heard on the other side of it. He had started on the newspaper, and was reading the most interesting stories aloud to Mother.

"Bad atmosphere," whispered Fanny.

Erich nodded. "I don't understand why. All because of this Hitler."

"He's going to be chancellor. The election's on Tuesday."

"So?" asked Erich dismissively.

Fanny was whispering again. "He hates your people."

By your people, Fanny meant Jews. Being a Jew was no big deal for Erich. He didn't even know when he'd first realized that he was Jewish, not Catholic or Evangelical like his friends. It was perfectly normal, it was a part of life, like getting up in the morning, washing, eating, drinking. So their special day was Saturday, the Sabbath, not Sunday, but all the same he and Max had to go to school and Father had to see to the cattle and deal with customers. They celebrated Pesach instead of Easter, but Mother still hid eggs and chocolate rabbits for him and Max, and gave the neighboring children a taste of fresh matzo. At Chanukah, the Levi family had a Christmas tree like everyone else.

To Fanny, he said, "That's nonsense! I mean, sure, we were persecuted in the Middle Ages, when a lot of Jewish people dressed differently and had different customs, but it's not like that these days."

Fanny shrugged her shoulders. "I think it's ridiculous too. Still, I've heard that Hitler says the Jews want to destroy the German people."

Erich began to laugh. "Well, so now you see how idiotic it is. I mean, we're Germans ourselves!" He helped Fanny to carry the good china into the living room.

"Off you go, Fanny. I can see your feet itching to start dancing!" said Mother with a smile, and she began putting the glasses and plates away in the sideboard. Max, who had come downstairs after all, helped her.

Erich sat down at the big dining table under the round porcelain lamp that gave a bright, warm light. There was only one plate left on the table, the Sabbath plate. On Friday evenings Mother took the candlesticks and Sabbath plate out of the cupboard and arranged the loaves of challah on it. They lay there under an embroidered white cloth until after prayers, when Father solemnly broke the bread and gave everyone a piece. The Sabbath plate symbolized the festive Sabbath mood; it reminded Erich of good food, of being allowed to stay up late even though there was school the next day, Saturday, and of the warmth and security of the family meal they ate together. Erich carefully picked up the plate.

There were Hebrew letters in a circle around the rim. After two years of studying Hebrew, Erich could decipher them easily. "And the evening and the morning were the sixth day." Beside the Hebrew inscription were small painted symbols, oddly shaped triangles. No one was sure what they meant. Suddenly, however, he remembered how he had thought of those signs when he was a little boy: eyes. The eyes of God looking at us.

Excerpted from SOMETHING REMAINS © Copyright 2011 by Inge Barth-Grözinger. Reprinted with permission by Hyperion Books. All rights reserved

Something Remains

- Genres: Historical Fiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Hyperion Book CH

- ISBN-10: 0786838817

- ISBN-13: 9780786838813