Excerpt

Excerpt

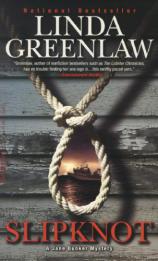

Slipknot

Chapter 1

“Why did you move the body?”

“The tide was coming in.”

I was relieved that my now seemingly stupid question was not flagged as such by either tone or content of reply. The man I was soon to know as Cal Dunham spoke in an oddly pleasant, nicotine-stained voice. His reply revealed no inflections of “dumb broad,” nor did he voice any of the questions that I assumed he might have liked to ask me. Why and how had I appeared, notebook and pen in hand and camera slung on shoulder, at the crack of dawn in the seaweed-strewn and barnacled ledges below the west side of the pier at Turners’ Fish Plant in Green Haven, Maine, just as the body of Nick Dow was discovered washed up on the beach? Cal hadn’t asked. So I assumed there was no need to tell him that I was a rookie marine consultant on my first assignment. I also needn’t tell him that I was a freakishly early riser and had wanted to flounder through this initial survey of Turners’ Fish Plant and property without witnesses to my newly embraced learn-as-you-go style.

“Jane Bunker,” I said, leaning forward and offering a hand.

Although his hand was rough and calloused, his grip was as light as that of any man who’s uncomfortable shaking hands with a woman. “Cal Dunham,” he said hesitantly, as if unsettled by the normalcy of introductions in this extraordinary scene starring the dead body. Then -- out of politeness, I supposed -- Cal motioned at the body with an open palm and said, “Nick Dow.”

Nick Dow -- wasn’t that the name of the man who had caused such a scene at last night’s town meeting? It was impossible to make a positive ID while seeing only the back of a head, and a badly smashed one at that. Someone had hit him with something heavy to crush the back of his skull so thoroughly. The dark hooded sweatshirt was similar to what half of this town’s population wore, so that was not a defining detail. The rope used as a belt was probably a staple in the Maine fashion scene, I thought as I snapped some pictures. Was this the same guy? I would have to check with my favorite chatterbox waitress at the coffee shop. Lucky for me that the first and only friend I’d made since moving here three days ago was the girl serving coffee. Audrey knew all and told all.

Once I’d established for Cal that I was not a reporter for theMorning Sentinel, and that I was a marine investigator employed by Eastern Marine Safety Consultants, and that I was indeed not “like the fireman who played with matches,” my acquaintance of only five minutes was somewhat more forthcoming with information. He politely addressed me as Ms. Bunker, even after I insisted he call me Jane. He relaxed a bit and straightened from his crouch over the body, but for the large mass above his shoulder blades. Cool, an authentic hunchback, I thought. They’ve got one of everything in this tiny town.

Although my first instinct was to bombard Cal with questions to satisfy my growing curiosity about the dead man, and to note any theories he might have as to the whys, whos, and hows, I remained quiet, with my eyes riveted on the badly fractured skull. I didn’t ask Cal a thing; I vainly believed I had somehow subliminally compelled him to share all he knew with me. But as disillusioned with my own extrasensory powers as I was, I must admit that Cal Dunham was simply presenting me with his alibi. The covering of one’s own butt is powerful incentive while standing over a dead body.

This June twelfth had begun just like every other day in the past six years since Cal Dunham’s retirement from offshore fishing, or so he told me as we conversed over the waterlogged corpse. He had risen with the sun, sipped a cup of Red Rose tea, and enjoyed a Chesterfield cigarette before slipping out the door without waking Betty, his wife of nearly fifty years. He had driven his Ford pickup the potholed three miles to Turners’ Fish Plant -- his place of employment, along with nearly everyone else in Green Haven who didn’t go to sea. He had arrived one hour before the plant was officially open, sometime after the owner and bookkeeper, Ginny Turner. “The owner of the plant is your boss, and she’s at work before you?” I asked, thinking about my experience with bosses and not recalling any who were on the job prior to me. Suspicious, I thought.

“She’s part fish,” Cal said in defense of his boss. “Certain types of fish surface at night. She spends the wee hours accounting bait, fish, lobsters, and clams bought and sold the previous day, settling up with the fishermen and diggers, and taking phone orders from customers down the coast to be packed and delivered each day. Everyone else in Green Haven is tucked into bed when Ginny is most productive. Everything was as usual until I got out of my truck and saw Ginny at the end of the wharf. She’s always up there” -- Cal pointed to a second-story window overlooking the harbor -- “hovering over the company checkbook like a gull on a mussel.”

“What was she doing on the dock?” I asked impatiently. “And what were you doing here?”

I didn’t bother explaining to Cal that I was not here to investigate a murder, as old habits are hard to break. I listened intently as he continued to fill in some blanks. “I guess I’m what you’d call the foreman around here. I take orders from the queen and give them to the worker bees. I always come to work early, just habit,” Cal explained. “Anyway, when I looked to see what she was gawking at, there was ol’ Nick, facedown.”

Cal said that he and Ginny quickly agreed she should call someone while he pulled the cold and partially rigor-mortised body out of the incoming tide. “I figured she’d dial up the sheriff or the county coroner. Never thought the insurance company would get here first. Ain’t that just like people, though? Worried about their pocketbooks, with poor Nick here as dead as he can be.”

Oh, how I was enjoying the flow of information I was not really privy to. And the unsolicited editorializing absent any intimidation from me was a gift. If I had stumbled upon a similar scene back in Miami, there wouldn’t have been a drop of information that didn’t first come through the filter of an attorney.

Cal appeared ill at ease in the presence of a female he assumed was here to question him regarding the body. From what he said, it seemed that his boss feared a wrongful-death suit, since the body had washed up below her dock. Again, Cal hadn’t asked. So I would not confess that I was actually here to do a routine safety examination and survey of the fish plant and surrounding properties for insurance purposes. Coincidentally, this body had washed ashore. I’ve always been lucky that way.

I shrugged at Cal’s disgust that I had arrived on-scene before the law enforcement officials. Accustomed to even less enthusiastic greetings, I began pacing off the piece of jagged shoreline between two rickety, slime-covered ladders secured to the west face of Turners’ dock. “Well, if you ask me, which you have not,” Cal continued, “you might want to do some moonlighting here at the plant. I think you’ll find there ain’t a lot to investigate in Green Haven -- not like Florida. Dead bodies on the beach don’t occur too much here.”

Ah, there it was. A bit of my past had arrived in Green Haven. I snapped a few photos and jotted something in my notebook, but my mind was now occupied with questions unrelated to the scene. I wondered how much this stranger knew about my circumstances other than that I had come to Maine from Florida. Did he know that I had willfully given up a position as chief detective in Dade County to take this entry-level job? Did he know why I had chosen Down East Maine and the Outer Islands as my coverage territory? I checked my paranoia. Of course Cal couldn’t know any of this. It was all very complicated. Hell, these were things I didn’t fully understand myself. Without realizing it, I was staring at Cal as if trying to see into his head. He stood over the body, his well-toned, muscular arms across his chest. His full head of perfectly white hair was cocked to one side as he inspected my every move while guarding his fallen comrade. His countenance was grave but for a playful spark in his blue eyes. He had a calm about him that I found comforting. I liked Cal. He looked exactly the way I had imagined a seventy-year-old New Englander. Except for the hump, he looked like Robert Frost. Perhaps apprehensive with what may have been misunderstood as an admiring gaze from a much younger woman, Cal asked, “Why did you decide to come back to Maine after all this time?”

So, Cal knew more of my past than I had hoped. I gave him the short, rehearsed, and totally believable response: “Just tired of drug runners with fast boats and Haitians on inner tubes.” I had no desire to confide in Cal the more personal reasons for my move. The fact that a relationship gone bad had resulted in my mentor’s imprisonment was something I might never reveal. I grinned as I measured the gap between the lowest two rungs above my head. I released the bitter end of the metal tape, letting it recoil freely into the plastic housing with a sharp snap that punctuated the end of this topic of conversation. The gene responsible for the gift of gab had skipped a generation in my case, which was an obstacle I overcame on a daily basis. In the absence of anything worthy to say, I always bailed out of meaningful conversation or uncomfortable topics with sarcasm. In the most extreme situations, my responses were suitable for print on bumper stickers. Nervousness clipped my half of a dialogue to what I was once told could be read on any of the triangular wisdoms espoused by a Magic 8-Ball. Cal did not make me nervous, but his question had.

“Why not change careers?” Cal asked. “Seems easier than uprooting and moving all the way to Green Haven, Maine. Did you ever consider going back to school for something . . . well, something more appropriate, like nursing or hairdressing?”

Twenty years ago I would have jumped on Cal for his male chauvinism. At the age of forty-two, I didn’t jump much anymore. Besides, I knew he meant no offense. I would have to get to know him a lot better before filling him in on the real reasons for my move north.

Apparently keen to my consternation, Cal politely took his cue to change the subject. “I don’t suppose the ladder was the problem. Nick was a good enough guy, even though he did irritate folks. He has a knack for pissing people off, but not to the point of homicide. Has a long history of getting liquored up at night when he’s not offshore.” The level of intoxication might account for the number of belt loops he missed while threading the old piece of rope around his waist, I thought. Perhaps threading a belt should be part of roadside sobriety tests. Cal went on, “He must have come here with a skinful and walked right off the dock. He doesn’t have any family that I know of, so I wonder why Ginny would worry about getting sued. It’s not that I don’t like your company, but you are wasting your time here.” So, I thought, human nature held its ground even this far north of the Mason-Dixon Line. My best friend and mentor had taught me this lesson long ago. Disinterest was the best lure for information. The less attention I paid to the corpse, the more I learned about Nick Dow. My mentor’s wisdom hadn’t been enough to keep him out of prison, but that’s another story.

I repositioned myself to photograph the entire wharf, stepping over the body as comfortably as if I were straddling a length of driftwood left by the last ebbing tide. Cal spoke softly and fondly of Nick, clearly having trouble referring to him in the past tense. As I jotted a few notes and numbers on the first page of a fresh legal pad, I heard hurried footsteps thunking along the weathered planks of the dock above: at first faint, then close until stopping.

“Is everything all right down there?” The voice was as nervous as the approaching treads had been. I held the legal pad in a salute, shading the rising sun, and took a long look at Ginny Turner while waiting for Cal to answer the query I supposed was meant for him. Clearly not the most complimentary angle for a woman of such girth, I thought as I silently counted the rolls of lard like the rungs of the ladder. Ginny Turner was immense -- even her forehead was fat. It was impossible to discern where the chins stopped and the chest began. My mental tally was interrupted at seven when Ginny announced in exasperation, “Oh, Gawd! Here comes Clydie! Of all people . . . Where is the fire department? I called 911 twenty minutes ago. Glad my house isn’t on fire. Did you have to leave him right there, Cal? Can’t you tuck his arm in? It looks like he died reaching for the ladder. Why did he have to die here?” Off she went, quicker and more gracefully than her aerodynamics suggested, presumably to make another call for help.

“Who’s Clydie?” I asked Cal before the man now clambering over the ledges toward us could hear.

“Clyde Leeman, otherwise known as the harbormaster, is the town busybody. He ain’t quite right in the head -- a simpleton. He’s harmless. Loves to complain and gossip, like a woman. No offense intended.”

“None taken. In my experience, all harbormasters are simple.” I was delighted to think this absence of intellect was a prerequisite for the position I had tangled with in every major port south of Charleston, South Carolina.

“He ain’t really the harbormaster, although he acts like it. Clydie lives on top of the hill overlooking the whole harbor and a good part of the town. He likes to talk, and loves to put the stick in the hornets’ nest.”

I could think of several people fitting that same description, and knowing it was best to avoid one whose life’s ambition was to cause trouble, I made my way under the pier, over a ledge, and up a ladder on the opposite side before Clyde reached the beach now below me.

“Well, well, well, what have we here? I came down as soon as I heared the report on my police scanner. Oh, no. Oh, dear. Poor Nick Dow. I knowed it was him by that purple sweatshirt. Did you find him, Cal?” Clyde asked from under a chocolate-brown cowboy hat that looked more out of place than the body in the kelp.

“No. Ginny did. Speaking of Ginny, you know she don’t want you on her property,” Cal said as nicely as he could, considering the message was “no trespassing.”

Clyde pushed black-rimmed glasses up the bridge of his nose and took a deep breath. Bouncing slightly on the balls of his feet, agitated, he exhaled. “I come all the way around the fence! I’m below the high-water mark! This ain’t her property. The old bitch! She had no reason to fire me. I got a lawyer. He says I got a case. The money don’t mean nothing to me. I don’t care, but, but, but . . .” Clyde was sputtering like an outboard motor with water in the gas. I thought I saw him wipe a tear from under his glasses. Clyde continued a bit louder and faster. “I wouldn’t work here again if they begged me. They said my eyesight was bad. Didn’t trust me with the forklift no more. Well, I had my eyes checked and got a certificate says I’m fine. My lawyer says I got a good case to sue her ass. I don’t want no money. It don’t mean nothing to me. It’s just the principle of the thing, Cal.”

Before Clyde could draw another breath and resume the verbal pounding of his former employer, a siren could be heard coming from the direction of the center of the village. The siren served as fodder for Clyde’s next thought, which he was quick to share. “Here come the Cellar Savers! Green Haven’s finest! I ran for fire chief last election, and would have won, too, if that bitch hadn’t turned the whole plant against me. If I was chief, I would have been down here today before me!”

Clenching my teeth to contain a chuckle, I inspected the plank decking on the top of the wharf. Clyde turned up the volume another notch to be heard over the nearing siren. “Who’s that girl?” he asked. Cal explained that I was a marine investigator doing some work for an insurance company, to which Clyde gleefully exclaimed, “Oh, yes indeedy! She’s going to sue Turners’, too! Wrongful death due to negligence and lack of maintenance around this dump. Hey, girlie, look at them spikes, heads all stuck up proud like that. Anybody could trip on one and fall down here and smash his foolish head wide open. No railings! Did you get pictures of this ladder? How do you expect a man to climb out of the water with his head all stove in when he can’t even reach the bottom rung?”

I did my best to ignore Clyde. Cal didn’t bother explaining to Clyde that the “girlie” was ultimately on the side of Turners’, whose insurance company would be on the defense in any lawsuit, should there ever be one, which, if Cal was right about the possible scenario, would never be filed. I was only doing my job, just in case.

Forgetting or ignoring the fact that he was no longer welcome on the premises, Clyde diligently made his way to the top of the dock, where he became busy shouting directions at the man behind the wheel of the ambulance. With the way his shouted instructions and hand signals diametrically opposed each other, it was purely coincidental that the converted bakery delivery van negotiated the tight three-point turn without meeting the demise suffered by Nick Dow. The makeshift ambulance came to a stop, followed closely by a police car sporting bold lettering -- HANCOCK COUNTY SHERIFF. Two teenagers, one in fisherman’s boots and the other in stylish athletic shoes, stepped out of either side of the ersatz ambulance. Cal said hello to them, calling them by the names Eddie and Alex. Eddie, in the boots, had frizzy blond hair and eyes that had that puffy pot smoker’s look; Alex was clean and alert, with black hair and eyes that flashed with what I discerned as sheer irritation. I was certain Alex was the young man who had been humiliated in front of the entire town last night.

Visibly uncomfortable with the task at hand, Eddie and Alex stood waiting for someone, anyone, to tell them what to do next. A uniformed officer emerged from the police vehicle. He stood erect and ceremoniously placed a wide-brimmed hat identical to the one worn by Clydie upon his flat-topped head, prompting the first greeting. “Howdy, partner.” Clyde swaggered closer. “I’ll bet you wish you’d deputized me when you had the chance. Could have saved you a trip today.”

The sheriff dismissed the overzealous Clyde with what could have been interpreted as a nod but could as easily have been a nervous twitch with no intended significance. Clyde shadowed the sheriff as he conducted a thoughtful and methodical surveillance of the area, looking everywhere but at the body by Cal’s feet. The two ambulance attendants, still awkwardly awaiting instruction, stood dumbfounded, with their hands shoved deep into their dungaree pockets. Eddie’s jeans were well worn and ragged at the cuffs, which dragged on the ground. Alex’s Levi’s appeared to be new and had crisp creases that ran the length of his lanky legs. Amused and intrigued, I found their unfamiliarity with this scene of death strangely refreshing.

My presence was so conspicuous that the newcomers on the dock must have assumed I had a very good reason for being there -- although all three waited for a clue to my identity rather than risk a question they figured even Clydie knew the answer to. I began double-checking all measurements and digital images I had captured thus far. The sheriff donned mirrored trooper glasses so that he could more discreetly watch my actions. Clydie patted his own breast pockets for sunglasses and disappointedly came up empty. “Will you gentlemen please help me with Nick before the tide reclaims him?” Cal sternly yet politely interjected into the confused silence.

“Sorry it took us so long to get here, Cal,” said Eddie, who, on closer inspection, indeed appeared to be stoned. He opened the back door of the van. “We were about to leave the dock at the sound of the cannon when Ginny called on the VHF and asked if we could help out by driving the bakery truck -- um, ambulance. I was hoping we could get an EMT to come over, but I guess they’re both racing to get offshore for the new season, too.” Alex remained silent as he shot Eddie a look of disgust that I assumed was prompted by impatience with his partner’s apologies and explanations to the group of adults with whom Alex clearly had zero interest. The young men worked mostly against each other but finally managed to wrestle the stretcher from the back of the ambulance while Cal explained that it was too late for an EMT and that they needed only to deliver Nick to Boyce’s funeral parlor.

“Twenty minutes till the shot of the cannon!” Clydie enthusiastically announced, holding his wristwatch a mere inch from his face. “Eleven boats all fighting for next year’s quota. The newspaper says it will be like Survivor, The Amazing Race, andDeadliest Catch all rolled into one. The government’s really gone and done it this time. A lot of folks will be pretty upset about Nick’s pool, too. Hell, I put a ten-spot on the Sea Hunter myself. Guess I can kiss that farewell, to judge by the status of my bookie.” On and on Clydie rattled. The men, accustomed to his prattle, paid little attention while I discreetly took a few more notes. “Hey, his back pocket looks empty! Cal, did you take his black book? I sure would like to have my ten bucks back. Maybe the book and all of that money is drifting around the harbor!”

The parking lot adjacent to Turners’ Fish Plant was quickly filling with cars and pickup trucks and a steady stream of employees. Women in hairnets, and men in the rubber boots that I had just now overheard referred to as Green Haven wing tips, trickled down the wharf and formed human puddles around the van they had come to know as the ambulance. Shallow gasps of scared surprise and sighs of sadness escaped the growing crowd of townspeople and plant workers as they realized the source of this highly unusual activity involving the county sheriff. The sheriff, clearly appreciating an audience, had scrambled down the ledge to join Cal, who had remained stoically by the body. With Clyde Leeman by his side, the sheriff tried in vain to appear at ease this close to a dead body in a town where, I couldn’t help but notice, the law was unwelcome. Except for Clyde, the Green Haveners moved away from the sheriff as he passed. Some shot dirty looks in his direction. In an attempt to justify his badge, the sheriff began directing the young men carrying the stretcher. “Lug that thing down here. Give them some room, folks. That’s it.”

Amazed and intrigued with the notion that perhaps nobody at the location -- with the exception of me -- had ever seen a corpse outside a silk-lined casket, I tucked my notebook into my messenger bag and closed my jacket over my camera. With hair that was neither long nor short, not really dark or light, and a build that could best be described as average, I had always been good at disappearing in a crowd. I wondered as I glanced offshore at the island that loomed in the distance, interrupting an otherwise pristine horizon, how my life would have been different had my mother not plucked me away from my island birthplace and planted me in South Florida. Yes, I thought, that must be the Acadia Island I had wondered and fantasized about. If I had been raised there, I wondered, would I be here now as a real member of this assembly? I must still have family there.

Florida had been the most exotic and faraway place my mother could imagine when she decided to escape Maine with her two children; my brother, Wally, was just an infant. I thought the three of us were moving to another country by the time the Ford LTD station wagon rattled over the border of Georgia and into the state that would become our new home. Nearly thirty-eight years later, I could still hear the whoop my mother let out when she read the sign welcoming us to Jacksonville, as clearly as I had from my cozy nest of blankets in the backseat of that old car. As if we had been chased the length of the eastern seaboard by something that couldn’t penetrate the northern border of the Sunshine State, my mother declared us free. So at the age of four, I decided that my mother was different from other mothers.

My familiar stroll down this well-worn path of imaginative memory was cut short by a high-pitched screech and a flood of tears from a woman right beside me. Too well dressed to belong in the scene, I thought, the screamer stood out in the sea of long white lab coats -- the plant’s traditional uniform. This woman’s reaction to the sight of Nick Dow’s lifeless body was telling. Perhaps they had been lovers. Except for this one outburst of emotion and a few gasps that had slipped from behind hands trying to contain them, this body had been viewed nearly as casually as an abandoned shell that once housed a hermit crab. I was struck by how different this scene was from the many I had witnessed in Dade County. Maybe this coolness was the Yankee way. Or maybe no one had liked Dow much. Ginny Turner’s reaction was significantly different. Ginny was quite dismayed at her own misfortune of a delayed start to this morning’s schedule. If this had occurred on one of Florida’s beaches, a southern Ginny would have closed up shop for the week and been home baking for the funeral festivities. There would be a lot of crying and carrying on. Someone would have thrown him- or herself on top of the body by now. These northerners were quite different. My mother had never meshed with Floridians. I was beginning to understand that the difference was ingrained. Although I had never known exactly what my mother had fled, I understood that my retreat north was every bit as calculated as hers had been.

As I brushed by the sobbing, overdressed woman whose face was buried in the neck of a consoling bystander, I heard single chopped syllables staggering through all her gulps and sniffles. From what I could piece together of the almost unintelligible hysteria, I knew that, at least in the mind of one woman, this death was not a simple drunken misstep off a dock. Something had “gone . . . too . . . far.”

Alex and Eddie, I learned from Cal, were high school students fulfilling their civic requirements for graduation; they were also sons of two of Green Haven’s most prominent cod fishermen. The sobbing woman was Alex’s mother. The boys were working as a team to maneuver a backboard type of stretcher alongside the corpse. Cal joined the two in rolling Nick Dow onto the clean white sheet covering the thin mattress on the board while the sheriff and Clyde held the opposite side of the stretcher, keeping it from sliding away on the slippery rocks. The body slowly shifted from stomach to side and flopped bluntly onto its back in the middle of the mattress, giving me my first formal introduction to the face belonging to the man I was struggling to remain disinterested in. The air was still -- even the gulls went mute. The five men surrounding the stretcher stiffened and immediately backed away. Spooked, Clyde Leeman stumbled and fell on his rear end, then crawled quickly away like a crab, his eyes fixed on what looked like a blood-filled hole in the middle of the deceased’s otherwise stark white forehead. “He -- he -- he’s been sh -- sh -- shot!” Clyde stuttered.

As naturally as the men had scrambled to distance themselves from the horror of murder, I moved in close with my camera clicking. The sheriff was on his radio, calling for assistance from the state police, as Ginny Turner tried unsuccessfully to pry her employees away from the scene and to their various jobs in and around the plant. A mixture of relief and disappointment was shared as I flicked the limpet from the deceased’s forehead. “Relax, folks. It’s just a seashell,” I said, impressed with my authoritative tone. The entire crowd let out a sigh. I zoomed in on the green campaign-style button pinned to the victim’s chest. I pulled out my notebook and sketched the pin with the same block letters: YES!; the “Y” was artfully drawn windmill blades. Just as I added a dot to complete a question mark, a shot rang out that momentarily stifled the chaotic motion and buzz surrounding the onlookers, now speculators and surmisers. I instinctively hit the deck by diving onto the beach. I rolled for cover behind a large rock and reached for the gun that I no longer carried. All jaws dropped, and eyes were on this strange woman lying in the seaweed.

Stunned and confused, I remained behind the shelter of the boulder, gathering my wits. Cal approached slowly with both palms up, as if to say, “I’m unarmed.” He offered me his large hand, which I gratefully accepted. He helped me to my feet and said, “That was the cannon shot signaling the start of the codfish season.” I tugged my jacket back into place and pulled a tendril of hair from my eyes, tucking it neatly behind an ear. After making certain that the only damage I had sustained was to my ego, Cal added, “You ain’t in Florida anymore, girlie.”

I paced around the square cloth until seven o’clock. Lincoln would be here any second, I thought. Not wanting to appear as nervous as I was, I decided to sit down and wait. Should I face the path? No, that would only make me look anxious. I spun around, putting my back to where Lincoln would soon appear. No, maybe side to was best. After all, I was expecting him, so shouldn’t it look like I was eager for him to arrive? Cross-legged Indian-style wasn’t much of a suggestive pose. Perhaps crossed at the ankles, legs stretched straight. No, too stiff. Not comfortable. Not relaxed. How about lying partway down, propping my top half up on an elbow behind me? That was comfortable. My tummy appeared nice and flat this way, too. What a perfect spot to see the stars, I thought as I looked straight up at the sky. The tops of the circle of giant spruce trees formed a crown through which I watched a blue sky dim in the fading light.

At seven-fifteen I reassured myself that all was well and that my watch was actually a few minutes fast. The sun was well below the tree line, and the air was cooling quickly. Seven-thirty had me wondering if I’d read Lincoln’s card correctly. But this had to be the only clearing, and I was certain the invitation had read seven. Maybe I had the wrong night. No, he was probably running a little late and would burst through the opening in the spruce any minute now, full of apologies and armed with a picnic he’d put together himself. My anticipation had surged from a pleasant tingle to a nauseating burn. At eight, I faced the sad reality that I had been stood up. I hadn’t thought it would matter this much. Feeling thoroughly defeated, I was angry not with Lincoln but with myself.

Well, no sense hanging around any longer. The mosquitoes had found me. I was cold and hungry. Standing up, I grabbed an edge of the tablecloth and gave it a good shake to rid it of any spruce needles or bugs. Just as the far end of the cloth fluttered to the ground, something tugged it, and a loud blast pierced the otherwise silent dusk. After two decades in law enforcement, I knew a gunshot when I heard one. Dropping to my belly and covering my head with both arms, I felt and heard another near-miss. This time I gasped. I had been set up to be killed—led like a lamb to the perfect spot. My life would end wrapped in a plastic checkered tablecloth.

The next slap on the stern was more severe and made me quite nervous. A stream of cold water blasted me in the face, awakening my worst nightmare. The ocean was surging over the stern and had forced its way into the engine room, flowing down through the spaces between the steel plates above me. The water must be rising quickly in the bilge below me, I thought. Although it was pitch dark, my sensation of partial submersion illuminated the horror. Pushing on the plate above me was useless. The weight of the water coming down was too great for me to overcome. Remain calm, remain calm, I thought as my steel casket continued to fill.

The Sea Hunter rolled to starboard. The volume of water yet to seep into the bilge sloshed and held the boat in an extreme starboard list, not allowing her to right herself. Bracing against the port side of the steel plate with the back of my neck and shoulders, I pushed hard with my legs from a deep squat to a low crouch and managed to move the plate aside, leaving an access just wide enough to squeeze through. A murky halo of light dawdling at the top of the ladder on the opposite end of the engine room was my catalyst for action. I needed to reach the doorway through which the rogue waves had flooded the engine compartment before the crew was able to latch it closed in a somewhat belated attempt to keep what remained of the airspace below them watertight.

Creeping along the low side of the engine room, I leaned against the port fuel tank, knowing that if the Sea Hunter suddenly listed the other way, I could be catapulted into one of the moving parts of the engine, which was, miraculously, still running. I waded through knee-deep water to the bottom of the ladder and held on tight as another wave broke over the stern and rushed the length of the deck. A mass of green water darkened the doorway above me. Gripping the sides of the steel ladder, I ducked my head and held my breath. A deluge of salt water sluiced down through the open door and onto my back, buckling my legs. When the water stopped, I raised my head to a shower of sparks on my immediate right. I scrambled up the ladder and onto the deck, where the water that hadn’t found the engine room door was rushing in retreat out the stern ramp. The noise from the engine room fell silent to the peal of raging wind and sea as both engines were snuffed out.

Excerpted from SLIPKNOT © Copyright 2011 by Linda Greenlaw. Reprinted with permission by Hyperion. All rights reserved.