Excerpt

Excerpt

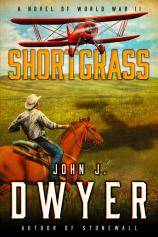

Shortgrass: A Novel of World War II

Thanksgiving day, 1934 Marlow, Oklahoma

The first time Lance saw Sadie, he had just taken a pre-game practice pitch from McClanahan, the Duncan High quarterback. He heard an odd buzz and saw something up in the air shining in the sun and coming toward the Mar- low fairgrounds football field from the east. It gleamed like a ruby against the cobalt blue sky. Everyone stopped what they were doing and watched, some applauding, as it motored right over the field, maybe fifty feet off the ground.

It was the last game of his high school career and the biggest, against Duncan’s close neighbor and biggest rival, the Marlow Outlaws, named for a proud tradition of outlawry commencing with the Marlow Brothers, who fought off an entire town that tried to lynch them down in Texas after they’d been crookedly arrested for cattle rustling. The two towns lay ten miles apart across the open prairie alongside the old Chisholm Trail. If Dun- can won the annual Thanksgiving Day rumble, the Demons would win the Southern Conference championship for the first time.

“There she comes,” someone in the near stands said.

The monoplane featured “MARLOW” in blue on the bottom of one scar- let wing and “OUTLAWS” on the bottom of the other. Lance had never seen anything like it.

Lookee at that girl flyin it, beautiful and bronzed, sportin a leather aviator’s helmet and a blue scarf the colors o Marlow. An flashin down a gleamin white smile and wavin. Wavin at me.

A wave of heat rolled across his face. Sullivan, Duncan’s other halfback, stood a few feet away.

Did Sully see me blush at that?

Handsome Sully’s daddy was county attorney and went after the gangsters when they robbed the bank in downtown Duncan or kidnapped the oilman out by Empire City or shot up the Marlow police force.

“If we the buckle o the Bible Belt like everbody tells us,” Sully had told Lance after one such encounter, “I hate to live somewheres else.”

Watching the plane circle over the field, Lance didn’t see how the pilot was old enough to fly it.

“It’s that Chickasaw girl flies,” Sully said as she set down in the pasture other side of Wildhorse Creek—named for a legendary Quahadi Comanche chief—beyond the south end zone.

“I think she smiled at me.”

Sully laughed. “Guess you ain’t heard about her out there on your farm? Wiley Post taught her. His brother lives crost the road from her.” He fielded a toss from McClanahan and trotted off, saying over his shoulder, “Think he picked out her plane.”

Lance stared toward the aircraft as the Chickasaw girl slowed it to a stop and clouds of reddish dust enveloped it.

Next to Lindbergh, Wiley Post the most famous aviator in the world. An’ he grew up around here. Dang! Then a football bounced off his ear, which rang and throbbed with pain from the force of it. Mad as hops, he turned to see Quanah “Chief” Bailey, Duncan’s full-blood Comanche nose guard, as tough a player as there was on the team, and Lance’s best buddy, lessen you counted Jeb his mustang.

“Leave the Indian girl alone,” Chief said with his own brand of smile that you never saw, but Lance knew was laughing somewhere inside him.

“Right,” Lance said, with a quick nod.

“Better getcher eyes off’n that girl and yer head outa yer tailpipe boy if ye wanna make it off that field in one piece today!” some Marlow fan hollered.

Lance chuckled.

They been revved up since we got here. Folks yellin thangs at McClanahan an’ me by name since we started warm-ups. That don’t hurt nobody, though. Heard as bad when we played Comanche an’ Lawton. Got em extree bleachers round the field, too, and I ain’t never seen more people show up fer a game. Looks like most o Stephens County’s here, and we got bout as many folks packin our side o the field as Marlow does theirs. Even a group from our church, and it’s a hour northwest o here.

Leader of that group was Lance’s Grandpa Schroeder—his mama’s daddy—who still preached at Lance’s Corning Mennonite Brethren Church and would be back in the pulpit Sunday to talk about his mission trip to Africa.

Marlow fought the Demons like the farmers fought the dust and drought and weevils, and like the ranchers fought parched pastures and sinking cattle prices. There was slugging and biting and cussing and slugging and fingers in eyes and neck-twisting and taunting and slugging and cleats stepping on hands and heads and slugging that cold sunny Thanksgiving Day. And wet little clumps of sod garnished it all from the heavy downpour two days be- fore, the first such on the hard ground in three years.

He had never before been called an “Amish traitor” guilty of, in some- what cruder terms, sodomy and cowardice, nor admonished to “git back to Germany” and perform more unnatural acts with the Kaiser. He figured they might have had the wrong guy, since he was Irish. They mobbed McClanahan so hard he had to leave the game for a series in the first half, but he came back, fire in his eyes.

“Time we kicked us some butt,” the quarterback said, eyeing Sully, whose broken nose bled crimson all over his white jersey. That caught Lance and the rest of the huddle up short, because none of them could remember if they had ever heard McClanahan say more than boo and the number of the play in the huddle.

Maybe I misheard him, though. My other ear from the one Quanah thumped is still ringin from one o them boys kickin it fore I could git up from the bottom of a pile.

Duncan moved the ball right down the field, Lance and McClanahan taking turns, McClanahan keeping to the left, then handing or pitching to Lance to the right. It was early in the second quarter and the game was scoreless, but Lance was determined to fix that. Duncan’s mascot, a shapely female student wearing a red get-up with horns and tail, waved a mock pitchfork in the air to rally the Duncan fans. Sometimes she led the students during school assemblies in reciting the school creed that hung on the wall of the gym. It exhorted them to become good Christian citizens. When Coach McAlister saw how hard they were coming for Lance and McClanahan, he called time out and rigged a bootleg play where McClanahan faked to Sully up the middle, then rolled out to his left. Coach knew Mar- low wouldn’t give his quarterback any daylight out there, so he told Lance to block for a count on the right side, then release downfield. That’s what he did as McClanahan hoofed it to the other side, half the Outlaw team lighting out after him. Just as they got there snarling and grunting to clobber him, he cocked and fired the ball back across the field, a perfect spiral that all Lance had to do was reach out his arms and pull in, running full stride and wide open. He made it all the way to the five-yard line before the Marlow safety, who had the angle on him, dove at his ankles and tripped him. A couple other Outlaws decided to make for sure he was down, plus crush his lungs out of his chest. That didn’t feel any good, but when he climbed to his feet after the referee didn’t throw a penalty flag, the Chickasaw girl stood a few feet away on the sideline looking real sad like she felt sorry for him, especially when he spit out part of a tooth. She was a Marlow cheerleader and had on a lamb-white wool sweater and long dress with a big blue M on her chest. Her thick, shimmering, black hair flew all over, and a luminous brown face and black eyes more lassoed than looked at him.

He stared back at her, then as the Marlow fans screamed as though they didn’t feel sorry for him at all, gave her an extra little limp as he turned and hobbled back to the huddle. He even glanced back at her and could have sworn she was still staring at him because she hadn’t moved a lick, but her pretty face had turned the direction he was going, and she bit her bottom lip.

Why she bitin her lip lik ‘at?

Duncan got inside the Marlow one-yard line and ran right at them, but couldn’t get the ball into the end zone. With the whole place screaming and both bands playing loud as they could, McClanahan faked the pitch to Lance, then ran the keeper off right tackle. Just after he crossed the goal line—the hometown referees said it was just before—one of the Marlow boys slugged the ball out from under his arm and it went squirting through the end zone and out toward Wildhorse Creek. Lance and a slew of Out- laws chased after it, forgetting about that new “touchback” rule they put in before the season.

The ball bounced up into a tall, lanky cowboy’s arms, but he couldn’t hang onto it, and it bounded into the creek. The cowboy stuck out a booted foot to trip Lance, but he got past him and jumped into the rare three-foot- deep current after the ball.

Dang ‘at water’s cold, but gotta git that ball!

Just when he reached for it, someone grabbed his ankle under the water and yanked him back. He half-turned and watched Sully stuff the grabber’s head down into the icy creek. He lunged free, snared the ball, sloshed to the opposite bank, and rammed it up onto the ground. A melee had en- sued among the players in the creek behind him, and several fans from both towns milled around nearby, shouting and cussing.

One fellow leaned toward him and hollered, “You’ll burn in Sheol, Hun!” When the Roarks’ Duncan farrier jerked the man around and slung him to the ground, Sully leaned over to Lance and said, his breath coming in gusts, “That guy jist cussed you? My daddy helped him with a land dispute. He’s a deacon at one o the Marlow churches!”

Then the refs blew their whistles and waved their arms and pushed everyone back and called that new touchback rule.

Shucks, we got snookered out of a touchdown twice. Dang. All right, Lord, You in control o all thangs, Sir. Reckon that must include even football.

That was the end of the first half, leastways the referees said it was, but he suspected they stopped it early to simmer down the adults.

During halftime, he tried various methods to get his mind off shivering in the Thanksgiving breeze on the Duncan bench.

Wonder whuther that Chickasaw girl seen me dive into the crick and git the ball?

Then Coach McAlister was hollering at them because they’d outgained Marlow three to one and not allowed them a first down, yet the score was 0-0. “And you do remember they ain’t won a blasted game all blasted year!” he hollered. Lance smiled to himself. “Blasted.” Yeah, Coach might get hisself fired if he didn’t win enough games, but he’ll sure get fired if he cusses at us.

“How we gonna be able to show our faces back in Duncan, we don’t beat these no-counts!” Coach McAlister concluded, kicking over the team’s met- al water cooler, which splatted top-down into the muddy goo around the Duncan bench.

So Duncan came out dominating in the third quarter, but every time they’d get down close, Marlow would keep them out.

It’s almost like God’s put a shield up around their end zone to keep us out, cuz they couldn’t do it on their own. That can’t be true, though, cuz He’s on our side, not Marlow’s. After all, the Bible never said God’s on everbody’s side, right?

Chief kicked loose a chunk of moist sod in anger a couple minutes into the fourth quarter with the sun dropping low behind the west grandstands and Marlow having just stopped the Demons again at the Outlaw twelve.

Could be trouble comin. Football field the only place he don’t feel like he has to watch his step real close around white folks in this country, only place where he can kick ever-lovin tail and not only get away with it, but get respect.

Chief had been yammering at the Outlaw line and quarterback now and again throughout the afternoon, but this time, when Marlow took possession of the ball, he commenced to unload on them.

“You bozos can’t get across midfield, much less into our end zone, even if we play till Christmas,” he said from down in the muddy trenches, loud as he could without the referees hearing it clearly. Then he barked out his own set of play signals, mimicking the Marlow quarterback.

On third down, Chief leaned across to Martin, the biggest and toughest Marlow lineman and the team’s captain.

“Tried to make sure I didn’t git your gnarly blonde nympho Sally Anne pregnant last night,” he said, mentioning some of her supposedly distinguishing features, “because I knew what folks’d call that half breed baby, but I can’t be sure.”

A couple of the Marlow boys tried to hold Martin back as the ball snapped, but he got loose and piled into Chief while Lance got his twentieth tackle of the day red-dogging the Outlaw quarterback from his linebacker spot for a ten-yard loss.

While Chief and Martin rolled around on the worsening ground, grunting and cussing and slugging, one of the other Marlow players aimed a few stomps at Chief’s back with his cleats. Before anyone else could jump in, the officials kicked all three boys out of the game. By then, everyone on both teams was pretty riled, so Lance put his energy into blocking the Marlow punt on the next play. He caught the fluttering ball on the fly and commenced to set sail for the winning touchdown, only to get hauled down on the ten-yard line by several Outlaws—none of whom happened to be in the game at the time. Just as he was thinking he had won the game for Duncan, because the refs would surely call this a touchdown, a little episode unfolded a few yards away, near the Marlow locker room building. His teammate Bobby Diggs Brown, one of Duncan’s lesser football players but one of its better bull riders, let Martin know as he was leaving the field how that blonde girl was too skanky to go getting his tail kicked for in front of the hometown crowd on a holiday.

Martin took serious exception to that. He hauled off and cold-cocked the perceived offender from his blind side, knocking him flat and knocking him out. As tends to happen in such matters, however, he didn’t even hit the young man who made the comment, but by mistake, one of the nicest fellows on the Duncan team, and one of the few Baptist preachers’ boys in the area who was a true Christian and not a whoremongering drunkard.

Chief thereupon convened a war party of Demons who decided they had had enough Marlow hospitality. They piled into Martin and the cleat stomper like a swarm of chinch bugs hanging around and lighting into a winter wheat crop after a warm fall.

A few of the Marlow townsfolk noticed Martin had at last got himself in over his head and decided to help. They stampeded down onto the field and tore into Chief and company. The Duncan fans couldn’t believe their good fortune at this turn of events, because it gave them the perfect excuse to finally get down and conduct some business of their own with their Marlow friends and neighbors.

Lance stood amazed at the sight of both grandstands emptying onto the field and into each other. Folks wailed away, kicking, gouging, stomping, swinging anything they could get their hands on. One big Marlow fellow in overalls lifted one of the Duncan benches into the air. Lance wasn’t sure what he intended to do with it, and the cluster of Duncan folks that flattened him and the bench didn’t seem interested in waiting to find out.

Mama and Daddy and a few of their Mennonite family and friends were about the only people still sitting in their section of the stands, and Mama looked toward him, fretting.

Hey, where’s that black-haired Chickasaw girl?

He looked around, but didn’t see her anywhere. He saw plenty else.

None o this should surprise anybody.

After all, not only a bunch of former Duncan and Marlow football players came down out of those stands, but men who fought the Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne during the Plains Indian Wars, some who rode in the Oklahoma Land Runs, others that rode up San Juan Hill with Teddy Roosevelt, still others who fought Germans hand-to-hand in World War I trenches, and oil field roughnecks, sharecroppers, and ranch hands from all those groups and none of them. You might even say it was surprising that bunch sat still long as they did.

Lance had no time to ponder such matters. He sidestepped a Marlow player running at him like one of those Rock Island freight trains whistling its horn whilst churning through Duncan a few miles east of the Roark farm in the quiet nights of the shortgrass country.

Crud, two more comin at me!

And behind them, a posse of Marlow town fathers and flotsam and jetsam alike, apparently aiming to lay hands on him of the nonspiritual sort. I never run this fast before. Shucks, maybe I can make the OU football team.

Tearing across a pasture adjacent to the fairgrounds, still holding the game ball, he decided he would not settle for playing at Oklahoma A&M, Tulsa, West Texas, or any of the smaller state colleges that had offered him college football scholarships.

By gobs, I am gunna play for the Big Red, and I’m gunna run this fast ever’ day in practice and in ever’ game.

And he ran dang fast because he was dang scared.

He was pulling away from the Marlow folks, though a shiny metal high school band tuba sailed past his ear. Then he leaped over a narrow section of Wildhorse Creek and into another pasture.

Think I’m in the clear, but my lungs’re bout to bust. Wait, what’s ‘at?

He turned. The lanky cowboy who tried to trip him across the field be- fore halftime broke ahead of the “posse,” riding hell for leather on horseback and headed right for him, reins in one hand and a rifle in the other.

I know I can git that cowboy off ‘im, even with ‘im gallopin at me, but it might take hurtin the horse. Aw, I’ll keep runnin.

Then the horse was nearly on him.

Dang, ‘at horse’s fast!

Something strange stirred to his other side. The most surprising sight of his seventeen-year-young life. The Chickasaw girl’s bright red monoplane, motoring along the ground.

Lord, it looks heck of a lot bigger from ten feet away! If they can’t run me down with a horse, they gunna run me over with a dang airplane!

He had no idea how to deal with an oncoming airplane, even a slow-moving one like this, other than just to try and dive away from it, but then he’d be right in the path of that cowboy and his horse. Then a high screech sounded over the rumble of the plane engine. The Chickasaw girl, screaming at him.

Goodness gracious, these folks take their football serious!

Panic was finally setting in as she waved her hand and the shadow of the cowboy raising his rifle to clobber Lance over the head fell between him and the sun. But the girl was pointing at a second seat, behind her and empty. He bruised a rib and knee reaching high and pulling himself up by ladder rungs attached to the moving plane, then landing head first in the little compartment. The horseman knocked off one of his cleats as he did. Then his body lay stuffed head-first into the second seat. The girl laughed over all the noise and the plane lifted.

Grunting, he turned over and pulled himself upright as they rose from the moist but hard ground. Down below, as Duncan and Marlow enjoyed their brawl in the distance, the cowboy shook his rifle and shouted things Lance doubted his mama taught him to say. When the Chickasaw girl leaned around, her face glowing in the setting harvest sun as it lit the sky behind her all amber and shimmery and unforgettable, he did something his own mama sure didn’t teach him. As the girl banked the plane back around, he reared back and fired the game ball he still held down at the angry horseman.

He so busy gyratin and puttin on, last thing he’s expectin’s a football to come hummin down at him from forty feet in the air.

Maybe that’s why when it hit him square in the forehead, it knocked him off both his horse and his high horse and flat onto his back on the red Oklahoma clay.

Horror flickered across Sadie’s face, then she glanced back at Lance. Something in his expression must have caused her to lose concern, because she burst out laughing and so did he as she lifted the red plane into the gathering autumnal dusk.

“Who is that crazy galoot?” he called to her. “What?” “That guy with the rifle!” “Oh, him? He’s my fiancé!”

Shortgrass: A Novel of World War II

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 350 pages

- Publisher: Oghma Creative Media

- ISBN-10: 1633732037

- ISBN-13: 9781633732032