Excerpt

Excerpt

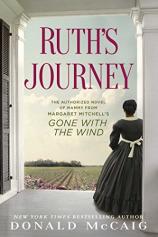

Ruth's Journey: The Authorized Novel of Mammy from Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind

Refugees

WHEN AUGUSTIN PRESENTED the solemn, beautiful child to his wife, the angels held their breath until Solange smiled.

Such a smile! Augustin would have given his life for that smile.

“You are perfect,” Solange said. “Aren’t you.”

The child nodded gravely.

After due consideration Solange said, “We shall name you Ruth.”

Solange had never wanted a baby. She accepted her duty to bear children (as it was Augustin’s failed duty to initiate them), and with enough wet nurses and servants to cope with infant disagreeableness, Solange would rear the heirs the Forniers and Escarlettes expected.

But as a child, while her sisters happily advised, reproved, and dressed blank-eyed porcelain dolls, Solange dressed and advised only herself. She thought her sisters too willingly accepted Eve’s portion of that primordial curse.

Ruth was perfect: old enough to care for herself and appreciate her betters without asking too much of them. Malleable and willing, Ruth brightened Solange’s days. She wasn’t the precious, awful burden an Escarlette baby would be. If Ruth disappointed, there were buyers.

Solange dressed Ruth as her sisters had dressed their dolls. Although lace was scarce, Ruth’s hems were fringed with Antwerp’s finest. Ruth’s pretty silk cap was as lustrous brown as the child’s eyes.

Since Ruth spoke French, Solange supposed her family had included house servants. Solange never asked: her Ruth was born, as if in her own bed, the day Solange named her.

One quiet evening, before Solange closed the shutters against the night air, a pensive Ruth sat at the window overlooking the city. In that dim, forgiving light, she was a small black African as mysterious as that savage continent and just as assured as one of its queens.

“Ruth, chérie!”

“Oui, madame!”

Instantly so agreeable, so grateful to be Solange’s companion. Ruth admired those characteristics Solange most admired in herself. Ruth accompanied her mistress to the balls and theater, curling up somewhere until Solange was ready to go home.

Assuaging Solange’s grave loneliness, Ruth sat silently on the floor pressed against her mistress’s legs. Sometimes Solange thought the child could see through her heart to the Saint-Malo seashore she loved: the rocky beaches and impregnable seawall protecting its citizens from winter storms.

With Ruth, Solange could drop her guard. She could be afraid. She could weep. She could even indulge the weak woman’s prayer that somehow, no matter what, everything would turn out all right.

She read fashionable novels. Like the sensitive young novelists, Solange understood what had been lost in this modern 19th century was more precious than what remained, that human civilization had passed its high point, that today was no different from yesterday, that her soul was scuffed and diminished by banal people, banal conversation, and the myriad offenses of life. The daily privations of a besieged city were no less banal for being fatal.

Captain Fornier was stationed at Fort Vilier, the largest of the forts ringing the city. The insurgents often tried and as often, with terrible losses, failed to penetrate the French forts’ interlocking cannon fire. Sometimes Captain Fornier stayed at the fort, sometimes at home. The flavor of his bitterness lingered after he departed. Solange would have comforted Augustin if she could without surrendering anything important.

Nothing in Saint-Domingue was solid. Everything teetered on its last legs or was already half swallowed by the island’s dusty vines.

There’d be no French fleet fighting their way through the British squadron. No reinforcements, no more cannon or muskets or rations or powder or ball. Without a murmur the Pearl of the Antilles faded into myth. Patriotic dodderers urged uncompromising warfare while Napoleon’s soldiers deserted to the rebels or tried to survive another day.

As their dominion shrank, the French declared carnival: a spate of balls, theatrical performances, concerts, and assignations defied the rebels at the gate. Military bands serenaded General Rochambeau’s Creole mistresses, and a popular ballad celebrated his ability to drink lesser men under the table.

American ships that slipped through the blockade sold cargoes of cigars and champagne and departed with desperate military dispatches and Rochambeau’s booty. Smoke rolled in from the countryside to choke the city until dusk, when it was dispersed by the sea breeze and the hum of clouds of mosquitoes. It rained. Great crashing rains overflowed gutters and drove humans and dogs to shelter.

Solange forbade Ruth to speak Creole. “We must cling to what civilization we can, yes?” When their cook ran off and Augustin could not secure another, Ruth made fish soups and fried plantain, while Solange perched on a tall stool, reading to her.

High officers sent officers on desperate missions in order to comfort their widows.

In Saint-Louis Square, General Rochambeau burned three Negroes alive. In an ironical moment he crucified others on the beach at Monticristi Bay.

Every morning, Solange and Ruth strolled the oceanfront. One morning, the quay was packed with chained Negroes. “Madame, we are loyal French colonial troops,” one black man shouted. Why tell her?

Ruth wanted to speak, so Solange hurried her along.

Two frigates sailed out into a beautiful day on the bay, and at low tide, three mornings later, the wide white beach was littered with drowned Negroes. The flat, metallic smell of death set Solange to gasping. When Solange complained to Captain Fornier, his weary, tolerant smile was a stranger’s. “What else would you have us do with them, madame?”

For the first time, Solange was afraid of her husband.

The morning everything changed, Solange awoke to Ruth humming and the piquant odor of coffee.

Solange pushed the shutters open on a dejected straggle of soldiers below. What day was it? Would Augustin come home today? Would the rebels mount their final attack?

Ruth said, “What does Madame wish?”

What indeed? How could she be so discontented without intending anything?

Solange touched the gold rim of her cobalt blue cup. These walls, the walls of her home, were brute unplastered stone. Shutters of some native wood were unpainted. Ruth’s eyes, like the delicate cup, were rich, complex, and beautiful. Solange said, “I have done nothing.”

Ruth might have said, “What ought you have done?” but she didn’t.

“Like a silly amateur sailor I have drifted into very deep water.”

Ruth might have corrected this self-appraisal but didn’t.

“We are in grave danger.”

Ruth smiled. The morning sun haloed her head. Ruth said, “Madame will attend General Rochambeau’s ball?”

Solange Fornier was Charles Escarlette’s daughter, redoubtable and shrewd. Why was she reading sentimental novels?

Ruth said, “The general’s ball will be held on a ship.”

“Does he mean to drown his guests?”

Ruth’s face went blank. Had she known one of those doomed prisoners? Solange sipped her coffee. At her impatient gesture, Ruth added sugar.

A cobalt blue teacup on a rude plank table. Sugar. Coffee. La Sucarie du Jardin. The Pearl of the Antilles. The air was clear and cool. Had the insurgents burned everything flammable? Solange could smell the faintest hint of the island’s beguiling florescence. How beautiful it all might have been!

“Yes,” Solange said. “What will I wear?”

“Perhaps the green voile?”

Solange put her finger to her chin. “Ruth, will you accompany me?”

She curtsied. “As you wish.”

Solange frowned. “But what do you wish?”

“I wish whatever Madame wishes.”

“Then tonight, you shall be my shield.”

“Madame?”

“Yes, chérie. The green voile would be best.”

When Augustin came home that afternoon, she surprised him with a kiss. He unbuckled his sword belt and sat heavily on the bed stretching his legs so Ruth could pull his boots off. “Poor dear Augustin . . .”

His puzzled frown.

“You aren’t cut out to be a soldier. I should have known . . .”

“I am a soldier, an officer . . .”

“Yes, Augustin, I know. Your frock coat. It is in our sea trunk?”

He shrugged. “I suppose. I haven’t seen it in months.”

“Make it presentable.”

“Are we going somewhere? The theater? Some ball or another? You know I detest these amusements.”

She touched his lips. “We are leaving Saint-Domingue, dear husband.”

“I am a captain,” he repeated stupidly.

“Yes, my captain. Your honor is safe with me.”

Perhaps Augustin should have asked what and when and why, but he was exhausted and this was too complicated. He pulled off his uniform jacket. In socks and pantaloons he flopped back, grunted, and began snoring.

He has aged, Solange thought—surprised by her husband’s lined, weary countenance. She fled this too tender mood with self-reproach: why have I abdicated my responsibility? Why should a Fornier determine the future of an Escarlette? “Rest, my brave captain. Soon, our troubles will be over.”

No, Solange didn’t know what she would do She had no words for the bright life flooding through her, that something that set her eyes and feet and fingertips tingling. She was certain of only one thing: they must escape the small island. They had nothing here, neither plantation nor rank, nor the false assurance that today would be the same as yesterday. If they stayed they would be killed.

Solange would know what to do after she’d done it.

———

It was pure Gallic genius to transform the poor old barnacle-encrusted, blockaded Herminie from a cannon-puffing, shot-hurling French flagship into an Arabian seraglio, with red and blue and green and gold scrims fluttering from yards and braces, potted palms stationed on the gun deck, and lamps and candles positioned to imperfectly illuminate nooks as lovers’ havens. A military band tooted gallantly, and officers in plumed silver helmets toasted Creole mistresses while Negroes in red and blue turbans slipped among them recharging glasses. In a palm grove on the quarterdeck, Major General Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, Vicomte de Rochambeau, greeted his guests. General Rochambeau was explaining the American Revolution (where he’d been his father’s aide-de-camp) to an American merchant captain. “Captain Caldwell, do you really believe that General Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington at Yorktown, ending the war and ensuring American independence? You do? Ah, Mrs. Fornier. You have neglected us of late. When was the last time we had the pleasure . . . the theater was it? That miscast Molière?”

The patch on the general’s powdered cheek may have covered a chancre, and when he pressed his lips to her hand, Solange repressed an urge to wipe it. “My dear general. In your company I had begun to fear for my virtue.”

Rochambeau chuckled. “Dear Mrs. Fornier, how you flatter me. Allow me to introduce Captain Caldwell. Captain Caldwell is Bostonian. The captain may be the only incorruptible man in Cap-Français. Certainly his is the only neutral ship.”

The general’s smile, like the man himself, was fleshy. “I don’t ask how many of my bravest officers have offered Captain Caldwell bribes—‘just a small cabin, monsieur’ . . . ‘a place in the sail locker’ . . . ‘deck passage’ . . . Captain, no names, please. I need my illusions intact.”

The American shrugged. “Money’s no good if you aren’t alive to spend it.”

Rochambeau had taken Captain Caldwell to Monticristi Bay, where skeletal remains testified as only they could. Rochambeau beamed. “How true. How very true.” He patted Ruth on the head. “Charming child . . . charming . . .”

As Solange withdrew, the general resumed his history lesson. “Lord Cornwallis was so chagrined at his defeat he wouldn’t attend the surrender ceremony, so, at the appropriate moment Cornwallis’s aide offered his sword to my father, the Comte de Rochambeau. The British surrendered to us French . . .”

The American guffawed. “That makes your father our first president. Anybody tell George Washington ’bout that?”

Solange whispered, “Discover. Learn everything you can,” and Ruth vanished like smoke.

The island’s passionate, primitive girls had rather disappointed Napoleon’s officers. Sad experience had proven that every alluring Creole girl had a brother in jail or a sister with a sick baby or an aged parent who couldn’t pay his rent. These dark-skinned succubi brought as many complications as satisfactions into their beds.

Solange’s usual escort, Major Brissot, was drunk, sprawled against the mainmast and barely able to raise his polished cuirassier’s helmet. She flirted dutifully with admirers, but what these gallants took for vivacity (some thought desire) was impatience. She knew what she wanted but not how.

Blackmail? On Saint-Domingue, who wasn’t corrupt? Who cared how many Negroes Colonel X had tortured and killed? General Y’s betrayal of French plans to the insurgents? Pish! Major D’s sale of French cannon to the enemy marked a new low, but, given the opportunity, what practical man wouldn’t have done the same?

In the end, Solange’s suitors sought easier conquests, and, beside her untouched champagne glass, she perched on the capstan waiting for Ruth and the child’s espionage. The moon marched across the sky, the military band grew discordant and put their instruments down. Laughter, glassware clinking, a curse, a shriek, more laughter. The American captain had gone off with a Creole girl. General Rochambeau had disappeared into the admiral’s cabin.

Chewing a heel of bread, Ruth perched on the capstan beside her mistress. She belched, covered her mouth, and apologized.

“Well?”

Whenever the wind changed and blew the British blockaders off station, Captain Caldwell would sail with many heavy chests (thought to contain treasure) consigned by General Rochambeau and an official pouch with military reports and favored officers’ requests for transfer carried by the general’s personal courier, Major Alexandre Brissot, Rochambeau’s sister’s son.

Alexandre had been shipped to the colony for conduct which, while not absolutely unknown was best practiced in a small—a very small—circle of peers. Alexandre had been indiscreet. Here, on the small island where murder, torture, and rape were commonplace, he’d been indiscreet again.

“He is a pede.” Ruth finished her bread and licked her fingers.

“Of course he is. Major Brissot is the only French officer who always treats ladies courteously.”

“Alexandre disgrace General Rochambeau.”

Solange blinked. “How could anything disgrace . . .”

“Alexandre and that boy, Joli. He loves him. Give him so many gifts other officers laughin’. When Alexandre uncle find out, he want kill Joli, so Joli run off. Joli ain’t come back neither. Best not.”

“Joli . . .”

“Alexandre warn Joli to run. General want hang Alexandre but can’t ’count he sister son.”

———

Many of the general’s guests had attained that plateau where they stayed erect by leaning against something and conversing with simple repetitions they needn’t recall in the morning. Servants had appropriated the wine, and the party was well beyond that point that cues the prudent lady’s departure. Sober soldiers guarded the admiral’s cabin. “Two,” Ruth informed Solange. “The general layin’ with two tonight.” Ruth grimaced. “Womens,” she specified.

Hope surged through Solange—not an idea nor yet a plan . . . “Ruth, back to the house. In my trunk with my other fabrics, you’ll find a red silk liberty cap. Bring it to me. Hurry.”

A discordant trio of junior officers bellowed a bawdy song: “Il eut au moins dix véroles . . .” A disheveled colonel and his Creole girl exited their candlelit privacy, clinging to each other. When one of Rochambeau’s guards winked, Solange pretended she didn’t see.

Hope waned, and Solange had almost abandoned her mad scheme when Ruth reappeared and draped the soft silk fabric over her hand. “Madame?”

Ruth’s presence firmed Solange. “Over there. That officer with his helmet in his lap. Wake him. Give the bonnet to Major Brissot and say ‘Joli.’ Solange carefully—oh so carefully!—told the child everything she had to say and do. “Ah, Ruth,” Solange said. “I trust you with our lives.”

With a downturned hand, the child dismissed her fears. “Little by little, the bird makes his nest.”

Solange set her trap in a cabin on the port side, where one small tin lantern illuminated empty champagne glasses and a rumpled coverlet on the narrow bed. She turned the coverlet over and fluffed it. For no particular reason, she stuffed the champagne glasses into a drawer.

When she extinguished the candles, beeswax sweetened the smell of recent sex. Solange removed all of her clothing, closed the lantern, and waited. Once her eyes adjusted, enough moonlight came through the porthole to illumine her trembling, very naked arms.

She heard a stumble outside the door. A clunk. A breathless male whisper. “Joli . . .”

The latch turned, and, naked, she enfolded her prey.

Seconds or several lifetimes later, the general burst in behind his nephew, bellowing, “Mon Dieu, Alexandre! You and Joli will shake hands with the hangman!”

Flaring lanterns. Other officers pressed into the cabin behind their general. Solange gasped and covered her nakedness like Eve in the garden. “Alexandre!” the general gasped. “You? This woman?”

The general’s round face leered over his nephew’s shoulder. “Dear boy! Dear boy! I didn’t . . . Don’t let me ruin your, your tête-à-tête.”

The general’s entourage matched his leer.

Solange scooped her gown, clutching it against her nakedness. “Alexandre is my . . . my escort. Please, sir. My husband must not know.”

He put a finger to his grinning lips. “Silent as the grave. He shan’t hear a word from us, yes, gentlemen?”

Murmurs and muted guffaws.

The general closed the door firmly behind him.

Solange took a deep breath and opened the tin lantern. Humming, and in no particular hurry, she dressed.

Alexandre slumped on the bed, his hands clamping his skull. He vomited between his knees and stared at the mess. Solange opened the porthole, wishing the general had left the door ajar. She buttoned her collar and fluffed her hair. “Pardon me for remarking, Major. But you are ridiculous.”

His eyes were so confused and sad, Solange couldn’t meet them. “Joli? I thought you were . . . His cap, I gave him that cap. Joli . . .”

“Doubtless your Joli is safe with the rebels. Perhaps he fights against us French. Monsieur, don’t try to understand all this. You will understand everything in the morning. May I suggest that tonight this bed is as good as any?”

“I love him.” He sobbed a racking, choking sob.

“Ah, monsieur. You were always kind to me.”

Ruth appeared in the doorway, looking her question. Solange said “Oui,” and the child smiled.

On deck, the stars had faded and the moon hung over Morne Jean. Here and there officers in elaborate filthy uniforms lay like battle casualties. A whore picking a fat captain’s pockets glared at the pair.

As she and Ruth made their way home, dawn lightened the ocean and gentle waves gurgled against the seawall. Solange took Ruth’s small hand in hers and squeezed it.

Later that same day, while Augustin and Ruth packed, Solange presented herself at General Rochambeau’s headquarters. No, she would not discuss her business. Madame’s business was of an urgent and familial nature.

After Solange got past his adjutant and shut the door, General Rochambeau greeted her with the smile crocodiles reserve for well-rotted corpses. “Ah, madame. So good to see you. Less of you perhaps, still . . . Tell me, Mrs. Fornier, my nephew is your escort?”

“Very often.” Solange blushed prettily. “The theater. He’s a marvelous dancer.”

“Just so. He . . .”

With some effort, Solange deepened her blush and said, shyly, “It is dear Alexandre I have come about . . .”

“Ah yes. Indeed. Madame, some wine?” He went to his sideboard. “Something stronger?”

“Oh no, my general. Last night . . .” (She touched her temple and winced.) “Ah, a married woman must not mix love with wine.”

“Madame Fornier, we neither create nor vanquish our desires. Until last night, if you’ll permit me, I thought Alexandre . . . Spirited young men . . . young men will . . . experiment. To find their true selves, is it not so?”

She smiled sweetly. “General, I must have your counsel. I am a married woman. But it is another I cannot get out of my head . . . his hair, his tender lips, his sensitive eyes . . .”

Had not his blushes been abolished years ago, perhaps the general would have found one now. Instead, he coughed. “As you say, madame. As you say.”

“We are destined to be one.” Groping for the appropriate sentiment, Solange cribbed from her sentimental novels. “Our love is meant to be. Alexandre and Solange. Our destiny is writ in the stars!”

Rochambeau poured a glass of something stronger. “No doubt.”

“General, my marriage . . . a Fornier is not an Escarlette, much less a Rochambeau!”

His nod acknowledged this self-evident truth.

“I accept Alexandre’s offer. But he is so . . . unworldly.”

“Alexandre’s . . .”

“We’ll need passports. After we reach France, Alexandre and I will seek our destiny!”

“Madame, I give passports only to the old and the ugly.”

“General, you are so, so gallant.”

“And Captain Fornier?”

“My husband accepts what he cannot change.”

“Very well. As you may have heard, my nephew is escorting dispatches to Paris. Major Brissot will need an aide. Does that satisfy you, madame?”

Solange clapped her hands together so smartly, the general winced. “Madame, if you please.” He drained his glass, hacked, and swallowed hard.

“I’m so sorry, General. Alexandre respects you above all men, and he is so hurt by those vicious calumnies. If my public embarrassment has refuted those lies, I am satisfied.”

Rochambeau rubbed his temples and turned hot eyes on her. “You have attained your goal, madame. Would you hazard it?”

“General, I do not take your meaning.”

“Madame, of course you do.” He rubbed his temples. “I had thought you . . . unexceptional. Now, I regret I shan’t get to know you better. I shall amuse myself, however, imagining you and Alexandre, as you put it, ‘writ in the stars.’”

“General, are you mocking me?”

He bowed deeply. “Dear, dear Mrs. Fornier, I would be afraid to.”

Three nights later high winds forced the British squadron into desperate tacks to hold their position. Although Captain Caldwell had assured Solange he’d notify her when he was ready to sail, Solange and her family boarded immediately. Solange feared one of those last-minute so regrettable mistakes. When Major Brissot and his improved reputation departed Saint-Domingue, the Forniers would depart too. A single portmanteau held their belongings, softer fabrics cushioning the blue and gold Sevres tea set. Jewelry, a few gold louis, and a charged four-barrel pepperbox pistol were stowed in Solange’s reticule. She had sewn her precious dower agreement and letter of credit into Ruth’s petticoat.

By morning, the British blockaders were blown out to sea and the horizon was empty of their sails, but Major Brissot didn’t appear until ten o’clock. Soldiers carried the general’s precious trunks aboard and then had to be mustered and counted and two deserter-stowaways plucked from hidey-holes before they cast off. Captain Caldwell was anxious; though officially neutral, American ships carrying French booty were legitimate prizes.

It was brisk and sunny, and the air was brilliantly clean. Beside Captain Caldwell, Major Brissot winced at two shots from the quay. “There but for the grace of God,” he murmured.

The captain urged his quartermaster to crack on more sail before turning to his important passenger. “A fine day, monsieur. Excellent. If the winds hold, we’ll make swift passage.”

Alexandre smiled sadly. “Good-bye, Saint-Domingue, accursed island. Your voudou men have cursed us. All of us.”

The captain sniffed. “I am a Christian, sir.”

“Yes. As are they.”

As the island sank to the horizon, a thin column of smoke lingered above what might have been a plantation, or a town, or perhaps a crossroads where men were squabbling, fighting, and dying.

Alexandre shuddered. “The Negroes . . . They love us, but they hate us too. I shall never understand . . .”

“You are well out of it.”

“I have left too much behind.”

Captain Caldwell grinned. “You have left less than you think. Have you inspected your accommodations?”

“Sir?”

When Alexandre stepped into his cabin, he was startled to find a small girl serving breakfast to a fellow he may have met somewhere, sometime, and a woman he remembered too vividly. “Madame!”

“Ah. Look, Augustin, it is my lover, Alexandre. Isn’t he handsome?”

The husband so addressed set his fork down to examine his rival equably. “Good day, Major Brissot.”

Solange said, “Alexandre, your uncle holds violent opinions about whom one may or may not love. My subterfuge spared you and restored your—and your family’s—reputation.”

Alexandre stuttered his outrage. Why, why had Madame Fornier involved herself in his affairs?

“Sir”—Solange smiled too triumphantly—“I have repaired your reputation at some cost to my own. Don’t I deserve your thanks?”

Apparently not. Despite steady winds and exceptionally fine weather, their voyage was awkward and unpleasant. Alexandre sulked. Augustin was depressed. Solange, who had spent her childhood on small boats, was intensely seasick. Ruth was the sailors’ favorite. They spoiled her mercilessly with sweets and taught her “American” English. A burly seaman carried her to the tip-top of the mainmast.

“I swayed out over the water,” she told Solange. “I could see all the world.”

When they landed in Freeport, a fast schooner was waiting for Alexandre and his uncle’s booty. Alexandre made an effort. “Madame, you are a formidable woman.”

“No, sir. I am ‘redoubtable.’ Your Joli is lost. Surely there are other Jolis?”

Alexandre examined Solange until her gaze faltered. “Ignorance is always cruel.”

Although he was sailing for Boston, Captain Caldwell would call at Savannah, Georgia, a city he assured the Forniers was prosperous, cosmopolitan, and where (nodding at Ruth), unlike Boston, slavery was legal. Solange had made all the decisions she could bear to make and Augustin couldn’t help. Savannah would have to do.

And, for just two louis, the Forniers could retain their cabin. A bargain, Caldwell assured them. The Irish immigrants he took aboard would have paid more.

Solange and Ruth took the air on the quarterdeck, ignoring the stares and just audible remarks of less fortunate fellow passengers. Solange did wonder if Augustin had left something very important on the island, but she didn’t ask. Her husband rarely left the cabin.

In shallow waters off Florida, the weather deteriorated, and the leadsman chanted night and day. Driving rain flogged the deck and the huddled Irish passengers. Two unfortunate infants died and were consigned to the deep.

As they pelted northeast, the rain relented but the wind was biting.

The captain reduced sail as they approached the delta where the Savannah River emptied into the Atlantic. “Mistress, mistress, come look!” Ruth pulled Solange to the rail and clambered up to see better.

“The New World.” A burly Irishman betrayed no enthusiasm.

Solange, fresh from quarreling with Augustin, did not need a new friend. “Oui!”

The man’s thick dirty hair was brushed back, and he smelled powerfully of the bay rum he’d applied in lieu of soap and water. “You’d be one of them Frenchies the niggers chased off?”

“My husband was a planter.”

“Terrible hard work, all that stoopin’ and hoein’.”

“Captain Fornier was a planter. Not a field hand.”

“Betimes rebellions overturns masters and betimes they overturns field hands. Turnabout bein’ fair play and all.”

“You, monsieur; are you too the debris of rebellion?”

“We are. Me brother and me, the both of us.” He smiled. Some of his teeth had been broken, all were stained. “Do you reckon it matters if the hand that fastens your noose is white or black?”

“Sir, don’t distress the child,” Solange said. “She knows nothing about such matters.”

The Irishman studied Ruth. “Nay, ma’am, I reckon this child knows a muchness.”

A pilot boat battered over the bar; a seaman in oilskins climbed the rope ladder and had a word with Captain Caldwell before taking his place beside the helmsman, hands clasped behind his back.

The ship eased up a channel through an estuary pocked with brushy islands and pale sandbars. It looked nothing like Saint-Malo. Ruth took Solange’s cold hand in her warmer one.

Reluctantly the tide loosed them to slip inland between a wall of gray-green trees dripping with ghostly moss and a vivid yellow-green salt marsh. Directly, this wilderness gave way to a port where big and little ships docked and anchored, beneath an American city on the bluff above their mastheads.

Augustin came on deck blinking in the sunlight.

Savannah’s bluff was faced with five-story warehouses, and staircases wriggled back and forth as if embarrassed by what space they required. The docks were frantic with carts and wagons while spindly cranes delivered cargo from ship to shore and reverse.

The pilot eased them alongside this confusion and scurried down his rope ladder indifferent to the shouted promises of New World hucksters: “I want your silks and by Jehoshaphat I’ll pay for them!” “British and French banknotes discounted! I have U.S. and Georgia banknotes in hand.”

After the gangplank was lowered, their meager possessions clasped fast, the immigrants hurried into their future. A small man in a white waistcoat and top hat confronted Solange’s Irishman. “Work for the willing. Stevedores, draymen, drovers, wherrymen, laborers. Irish and free coloreds treated same as white.”

As Solange came up the burly Irishman set his bundle down and inclined his ear. He shook his head no, but the small man clutched his sleeve, whereupon, pursued by his top hat, he was flung into the river. “And a Killarney greeting to you, my man. Selling work is a shabby business.”

“Silks, jewelry, gold or silver, gewgaws? Madame? You won’t find fairer prices in all Georgia.”

Solange brushed by with “Invariably, sir, those most eager to help strangers offer the least.”

The little family humped their portmanteau up three landings to Bay Street, a broad boulevard where coloreds unloaded cotton bales and rough-cut lumber into warehouses.

Solange rested on a wooden bench wiping her brow. Among the mercantile bustle, gentlefolk exchanged gay greetings, promenading through Negroes and Irish as if they didn’t exist. Solange felt poor.

Some shops facing the boulevard were busy, others silent as rejection. A six-horse lumber wagon rumbled by, off wheel squealing. Some coloreds were respectably dressed, others wore rags that scarcely observed the conventions of decency. River breezes refreshed the promenade. Solange dabbed perspiration from her brow. Augustin was pale, silent, and diminished. Augustin could not be sick. That would be too much! Solange elbowed her husband and was relieved by his querulous protest.

She sent Ruth to inquire for a moneylender. The coloreds would know who offered fair value. She told Augustin to remove his outer coat. Did he wish to poach like an egg?

Her husband’s smile begged for tenderness, an emotion Solange had less of. In this hard, uncouth new country, tenderness would impede her progress.

A dray braked as its driver berated another. They concluded their loud confrontation by leaning from their perches for vigorous, mutual backslapping.

Solange was so very alone. “Augustin?”

“Yes, my dear.” His too familiar, too flat voice. His damnable despair!

“Nothing. Never mind.”

Augustin did try. “Dear Solange. Thanks to your cleverness, we have escaped Hell!” His pale lips and jacked-up eyebrows seemed to believe it too. “Le Bon Dieu . . . ah, He has been so merciful.”

Was this the man she’d married? What had the island done to him?

Ruth returned with an elderly Negro in tow. “Mister Minnis, he fine honest Jewish gentleman, ma’am,” the Negro informed her. “He bein’ glad buy or loan ’gainst your jewels and gold.”

“Jewels and gold?”

“Oh, yes, ma’am. You pickaninny, she say how much you bringin’. King’s ransom. My, my.”

Before Solange could correct his misapprehension, Ruth dragged Augustin to his feet. “Come along, Master Augustin,” she cried. “Soon you be joyful again.”

At Mister Solomon Minnis’s residence on Reynolds Square, the servant left them on the piazza, assuring them that “Mr. Minnis be seein’ you straightaway, yes, sir: straightaway.”

At ten o’clock on a winter morning, Mr. Minnis was unshaven in nightshirt, slippers, and robe, but he bought their silks—including Solange’s green voile ball dress—and loaned against her jewelry and cobalt blue tea set. She could have payment in coin or scrip.

“At what discount?”

“Ah, no, no. No discount, madame. The notes are redeemable today, in this city in silver. A branch of the Bank of the United States is established in Savannah, and there’s to be a substantial bank building erected come spring. The cotton trade requires such.”

Each of Solange’s notes assured that the “President and Directors of the Bank of the United States promise to pay twenty dollars at their offices of Discount and Deposit at Savannah to F. A. Pickens, the President thereof, or to BEARER.”

“Satisfactory,” the bearer said, stowing her notes with the three silver Spanish reals that completed Mr. Minnis’s purchase and pawn.

As his Negro servant discreetly removed Solange’s valuables, Mr. Minnis asked about Saint-Domingue: Were the Negro rebels as brutal as reported? Were white women subjected to . . .

Solange said rebel atrocities were too harsh and too numerous to relate, but that was then and this was now and her family required accommodations during their stay in Savannah.

Although refugees and immigrants had strained Savannah’s modest housing stock and not a few families camped in the squares, Mr. Minnis knew a widow who might rent the coachman’s apartment over her carriage house.

They moved into two bare rooms that afternoon and Solange engaged a cook.

Impoverished immigrants competed for laboring jobs with colored servants, like Solange’s cook, who’d been rented out “on the town” by her master.

Since Augustin Fornier couldn’t “do” anything, he must “be” someone. Solange told her husband he was “a prominent colonial planter: one of Napoleon’s bravest field officers.”

After lifting her husband’s spirits, Solange made love to him. In the afterglow, Augustin fell into deep, satisfied slumber while the sweaty, discontented Solange lay stiffly at his side. Although Ruth’s regular breathing rose from the straw pallet at the foot of their bed, Solange didn’t think the child was asleep.

If necessary, a pretty maidservant would fetch a good price. Yes, Ruth adored her, and, yes, she was fond of the child, but one does what one must. What had Alexandre meant when he called her “ignorant”? Of what was Solange Escarlette Fornier ignorant?

Augustin snored his unimaginative drone and wasn’t up the next morning when Solange dispatched Ruth and Cook to the market and sat down to write Dear Papa! So Far Away! So Desperately Missed!

How Papa’s favorite daughter had suffered. Sucarie du Jardin had been a Fornier fraud! Her husband was useless. Had it not been for Escarlette wit, they’d be trapped on Saint-Domingue at the mercy of rebellious savages! Thanks to Le Bon Dieu they were safe in Savannah. If Papa’s favorite daughter had known then what she now knew, she would never have left Saint-Malo!

Solange didn’t promise Dear Papa a new grandchild, not in so many words. She only suggested that Dear Papa might soon have a happy surprise! She grieved over her pawned jewelry and cobalt blue teacups but scratched that sentence out. Dear Papa would have starved before he pawned one Escarlette treasure!

There was nothing for civilized French people in this hemisphere. Might she come home?

She wiped her pen and capped the inkwell. Morning sun poured through her window. Savannah birds haggled, and camellias flaunted fat, bawdy flowers. As she sanded and folded her letter, Solange felt a little less certain of what she had written. Perhaps . . .

Troubles had come so fast and in such bewildering profusion!

A not unpleasant lassitude crept into her bones; she was safe this morning, and American songbirds were auditioning for her approval.

Solange crushed coffee beans into a muslin bag and poured boiling water through it into her cup. The rich aroma tickled her nostrils.

She reappraised matters. They were in America; she, her husband, and the child who was almost more than a servant. If they returned to France, what were their realistic prospects? Poor Augustin would always be a second son, but in Saint-Malo he’d be the second son complicit in the loss of the Sucarie du Jardin, which Solange understood would grow more valuable in everyone’s mind the longer it was lost.

Negroes lived in Africa. What would happen to Ruth in Saint-Malo? When Solange’s ebony companion grew into womanhood (Solange shuddered to think), what would Solange do? In France, she couldn’t sell her.

Solange’s eldest sister had married a legislator and produced a healthy Escarlette grandson. Her second sister was affianced to a cavalryman and would, in due course, produce satisfactory offspring.

While Solange Fornier was the failed second son’s childless wife with an unusual very dark-skinned handmaiden.

She drank her coffee, waked Augustin, fed him a roll and an orange, and brushed flecks from his coat. She inflated his pride, insisting her hero was her Hero. “Brave men do what must be done.” She kissed him on the cheek and sent him forth into the world.

When Ruth and Cook returned, they were chattering in some heathen tongue, but when Solange evinced displeasure, Ruth begged pardon very prettily.

That afternoon, Solange walked to Mr. Haversham’s home, whose drawing room served (until the permanent structure could be built) as the Savannah branch of the Bank of the United States. The cherry wainscoting, florid wallpaper, and elegant ceiling medallion contrasted with the great iron safe crammed into the narrow doorway of what had been Haversham’s butler’s pantry.

Mr. Haversham studied Solange’s impressively sealed and notarized letter of credit. “Very good, madame. Please ask your husband to come by to open an account.”

Whereupon Solange laid her dower agreement beside the letter of credit.

Mr. Haversham ignored it while he explained, as if to a child, that, under Georgia law, Solange was a Fem Covert, and as a married woman could hold no property in her own name. He smiled agreeably. “Some liberal husbands accommodate their wives. Why, my own dear wife has full authority over our household accounts . . .”

Impatiently Solange unfolded and tapped the agreement. “You do read French?”

“Madame . . .”

“This attests to my right to hold property under my own name under the régime de In fiparatum de bient. Since this agreement preceded my marriage and was freely entered into by my husband, I am, under French law or the laws of any civilized country, a Fem Sole—exactly as if I were an unmarried female heir or widow. Should you require a translation, I can arrange one.”

The banker raised a mildly surprised but not disapproving eyebrow. “Madame, not every American is a provincial. I am conversant with French legal instruments.” He pushed his glasses back on his nose, and under a very large magnifying glass he scrutinized the document, its seals, signatures, and notarization. His chair squeaked when he leaned back. “Your documents are in order. Naturally I must have verification of your French balance before I advance your funds.” He plucked a Georgia Gazette from a wicker basket at his feet and opened to the shipping register. “L’Herminie sails this afternoon for Amsterdam, and she’s a fast sailor. We might have verification in . . . say . . . nine weeks?” He rose and bowed. “Your obedient servant, ma’am. Welcome to Savannah. I trust you will prosper here.”

While Solange would have welcomed advice on how that desirable outcome might be realized, she didn’t press the banker. As she strolled the broad, tree-lined, sand street in the pale November sunshine, Solange’s relief that her precious letter of credit was protected in Mr. Haversham’s sturdy iron safe was mixed with the apprehension a mother feels when her toddler is out of her sight.

Savannah’s French communities were two, not one. The French “émigrés” who’d come to Georgia after the 1789 French Revolution brought wealth with them, while most “refugees” were paupers who’d fled Saint-Domingue with little more than the clothes on their backs.

In December exiles and refugees got news which was no less distressing for being expected. The news flew from the docks to the lonely settler’s lean-to in the deep shadows of Georgia pines as fast as the fastest horse could deliver it. Saint-Domingue was lost! Henceforth the Pearl of the Antilles was a Black Pearl! Despite determined French resistance and terrible losses, the insurgents broke through the ring forts protecting Cap-Français and forced General Rochambeau to surrender. French officers and soldiers who could cram aboard rotting transports sailed only to become British prisoners of war; the wounded and sick left behind on the quay suffered for days before they were drowned. Triumphant insurgents renamed their nation Haiti.

That blow to French pride proved a blessing for one refugee family when Savannah’s second richest Frenchman, Pierre Robillard, showed his patriotism by hiring one of the defeated army’s gallant officers, Captain Fornier, as his clerk. Although Augustin’s salary wasn’t large, severe household economies and what remained of Mister Minnis’s loan would keep the Forniers until Solange’s letter of credit turned into cash.

Pierre Robillard had established himself in Georgia as an importer of French wines and those silks, voiles, and perfumes whose possession distinguished the newly rich Low Country gentlewoman from the rough-handed rustic her pioneer mother had been.

Pierre’s richer, younger cousin, Philippe Robillard, spoke the Edisto and Muscogee Indian languages and assisted the Georgia legislature during Indian land negotiations—an honor Philippe mentioned too often. The cousins Robillard dominated Savannah’s social season, and invitations to their annual ball were much sought after.

Georgia natives admired French urbanity but thought the new citizens too urbane, a little too French. The French lady’s shape, so clearly discernible beneath the shimmering fabric of her diaphanous gown, may have been unexceptionable in Paris or Cap-Français, but in Georgia, where backcountry travelers sometimes encountered hostile Indians and the Great Awakening had prompted many to reexamine their (and others’) sinful natures, those garments’ beguiling fragility seemed foolhardy and immoral.

Despite these mild adversions, Georgians were sympathetic to the refugees’ plight, and relief subscriptions were distributed by St. John the Baptist Catholic Church.

Low Country planters had vigorous, if differing opinions about the Saint-Domingue rebellion. Some claimed the slaves had been treated too harshly, others that they hadn’t been disciplined enough. Although every white Savannahian saluted Mr. Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death,” regarding Saint-Domingue, they believed the Jacobin passion for liberty had overreached by a country mile. Savannahians viewed the French Negroes with suspicion. Mightn’t they be contaminated by rebellion? Their flamboyant dress was provocative, and some French Negroes emulated white men, even flaunting watch fobs and chains! That spring, when news came of cruel massacres of whites who hadn’t escaped Saint-Domingue, many Masses were offered for their souls, and, for a time, French Negroes only appeared in their sober Sunday clothing.

Solange Fornier missed the sea. She missed Saint-Malo’s promenade, where salt rime damped her cheeks and her nostrils widened to seaweed’s astringent tang. Saint-Malo’s cobbled streets had known the footfalls of Romans, medieval monks, and bold corsairs. Savannah was so young, not much older than the revolution of which Americans were so inordinately proud. A few offered faint praise for General Lafayette, but of the French fleet that had denied reinforcements to the besieged British at Yorktown and the French troops who’d stormed the British redoubts, Savannahians apparently knew nothing. “You were our allies, weren’t you, when we freed our nation from the British yoke?”

Solange’s “yessss” was remarkably like a hisss.

France had bankrupted herself supporting these ungrateful backwoodsmen, and, because of that, the spendthrift King Louis had been beheaded. But that was then. Unlike some refugees, Solange wasted no energy regretting that French help for ungrateful Americans hadn’t been directed to its own rebellious colonies: Saint-Domingue in particular.

Solange exchanged her last two gold louis with Mr. Haversham. Though convinced that the Banque de France’s confirmation would arrive any day—“We must be patient, madame”—he could not, in his position of trust, advance money against it. Surely the charming madame would understand his position. He deplored the turbulent Atlantic. Several vessels, including a British mail packet, had failed to arrive when expected and were feared lost. Solange’s confirmation would not have been aboard a British vessel. Absolutely not! Non!

When Solange accompanied Cook and Ruth to the torchlit market building, she was overwhelmed by the number and force of so many blacks chattering away in their heathen tongues. Speak English! she wanted to shout. Or, if you must, speak French! Servants had no right to have conversations their masters couldn’t understand.

And the market women deferred to Ruth, a deference that annoyed Solange. White admiration for Ruth flattered the child’s owner as he who admires a Thoroughbred compliments the horse’s owner. But the market women’s strange deference conferred no benefits on Solange; the owner felt invisible!

Solange spoke English, but Augustin wouldn’t learn the language and dismissed American ways. After his workday, he lingered with other bitter refugees in a drinking house where French was spoken, Napoleon’s campaigns dissected, and the First Consul’s failure to save Saint-Domingue deplored endlessly. Solange nicknamed her husband’s new friends “Les Amis du France.”

Although Augustin had never set a sugarcane cutting nor, indeed, ever seen cane planted, he expertly debated colonial agriculture as if his brief visit to la Sucarie du Jardin had produced bumper crops.

Augustin insisted the new Haitian government would recompense him for the sucarie. (“They stole it from us, did they not? They must pay”) and to that end initiated a correspondence with the French consul in New Orleans.

Although Ruth’s English was the English of the market and servants’ quarters, the child was soon chattering away. While Augustin attended Pierre Robillard’s customers and gloried in Napoleon’s victories, Solange and Ruth explored the new world. Many mornings, just as cook fires discharged their first pungent smoke, Solange and Ruth strolled Savannah’s fine French squares, discovering which elegant homes belonged to which prominent families. (Ruth, who could go anywhere and ask anything, was a fine spy.) The French woman and her Negro maid visited neighborhoods where artificers worked, animals were sold, and lumber and bricks warehoused. The rude Irishman and his brother had acquired an oxcart and an emaciated, rib-sprung ox and set up as draymen. Though the Irishman invariably tipped his hat, Solange as invariably snubbed him.

Solange and Ruth often concluded their amble at the riverfront, below the deserted promenade on the cluttered, hectic docks, where Gaelic, Ibo, and Creole dialects loaded cotton bales and indigo barrels onto big and little ships and unloaded fine goods and furnishings off them.

Without Ruth, Solange might have been mistaken for one of the painted Cyprians soliciting dockworkers and sailors. Although some of these creatures tried to strike up an acquaintance, Solange spurned them.

Later, when there were more white faces about, the pair dallied at a small café for coffee and biscuits slathered with tupelo honey while Ruth chattered with everybody and anybody.

When they returned home, breakfast dishes and the lingering smell of tabac were her husband’s remnants. Solange changed from her walking garb and dressed the child for Mass. One time she’d attended the 6:30 Mass, which served Savannah’s draymen, stevedores, and laundrywomen. That Irishman approached without so much as a by-your-leave wondering how she was “faring” in the “New World” and had the effrontery to introduce “my brother Andrew O’Hara and Martha, my missus.” Despite Solange’s frosty silence, the man would presume on their brief shipboard acquaintance. Thereafter Mrs. Fornier and her maid attended the 10:30. If the 6:30 was the Irish Mass, the 10:30 was the Society. Solange didn’t repeat O’Hara’s mistake, nodding politely if and only if another nodded, and, in the vestibule after the service, she attended to her missal or rosary while familiars greeted each other with the ebullient chirps Savannah ladies preferred. When fine ladies remarked favorably, Ruth responded with a curtsy and “Thank you, mistress,” while Solange smiled distantly.

After the 10:30, gentlefolk boarded carriages for the quarter mile to Bay Street. Solange and Ruth walked and upon arrival promenaded quietly among their social betters. Were it not for the racial strictures, Solange might have been Ruth’s governess, instructing her and noting this subject of interest and that.

Those ladies Solange ignored in turn ignored her in favor of last night’s scandals and the all-too-delicious anticipation of scandals to come. They were particularly interested in matters that magnified their virtues.

After their promenade, Savannahians drove home, where supper and a nap fortified them for evening soirées.

Solange and Ruth went home and stayed there. Solange would not abandon herself to anxiety. (What would they do if the Banque de France failed her? What if her precious document drowned in the turbulent Atlantic?) Although she never priced Ruth, Solange knew the girl would bring more than Augustin could earn in months. Dull anxiety thudded against an anxiety backdrop. Solange was waiting for her life to happen.

She lost patience with the sensitive novelists who had been such good company in Cap-Français. To improve her English, she read Mr. Wordsworth aloud until she hit upon “Fill your paper with the breathings of your heart,” which reduced Solange and Ruth to giggling.

One overcast April afternoon when no ships made port and the day promised more hours than she could bear, Solange visited her husband’s place of business.

Most Bay Street establishments were brick, but some ramshackle one- and two-story board houses had survived the city’s fires and hurricanes. On one weathered veranda, a gray-haired ancient in frock coat and revolutionary three-cornered hat nodded at every passerby.

L’Ancien Régime, Monsieur Robillard’s emporium, was tucked between a chandlery and an apothecary. When she’d passed the place, Solange had always offered a cheery wave in case someone inside were looking, but she’d never crossed the doorstep.

On this occasion, Solange wore the dull clothing appropriate to a clerk’s wife, modified by Escarlette hauteur.

Ruth could wait outside. Solange was in no mood for complicated explanations, which, as a clerk’s wife, she would be obliged to provide.

She paused to admire L’Ancien Régime’s window: jacquard silks were draped over a gilt chair; the gold head of the cane propped against the chair was retracted an inch, revealing a bright lethal sword. Shapely crocks of emollients, unguents, and potions surrounded bottles of Veuve Cliquot against a broad fan of red, white, and blue bunting.

A bell jingled when Solange stepped into the dim interior, where a voice inquired if Madame had come for the new perfumes, which had been unpacked only yesterday and were, she was assured, the same scents favored by Empress Josephine when she and her ladies promenaded in the Tuileries.

At an altar of minuscule glass bottles, Solange presented her inner wrist to the clerk, who deposited a precious drop thereon. “The scent is inconspicuous, but, like the tuberose for which it is named, it blooms late.”

When Solange raised her wrist to her nose, it was the florescence of a May morning.

The clerk was tall, balding, and wore a ruffled linen shirt and navy blue cravat. Also, he was black; more precisely, he was gray-black, as if his blackness had been bleached by too much sun. His French was the French Solange’s Parisian cousins spoke when they condescended to visit delightfully quaint Saint-Malo. Solange introduced herself.

He bowed deeply. “Master Augustin has been keeping you from your admirers. I am Nehemiah, madame, your humble and most obedient servant.” His second bow was deeper and more presumptuous than his first.

“My husband . . .”

“Captain Fornier attends Master Robillard, madame. They read the newspapers. All the newspapers.” His head shake admired this unlikely accomplishment.

The man guided her down narrow passages between fabric trees, gold and white furniture, and artfully arranged cases of wine, to a door he opened without knocking. “Madame Fornier has this day, April the fourteenth, honored us with her gracious presence.”

Solange was issued into a narrow room, whose high ceiling was somewhere above the billowing cigar smoke.

How dare this Negro take charge of her! In icy tones, in English, Solange dismissed him.

As if she hadn’t spoken, Nehemiah lingered, to say in the same language, “Mistress Fornier, she like that tuberose. ’Deed she do.”

“That’ll be all, Nehemiah.” Augustin found his tongue.

Pierre Robillard came to his feet, ruddy face beaming. “So good of you to grace us with your presence . . . so good.” In the old-fashioned manner, he kissed Solange’s hand.

The office almost had room for two disreputable armchairs, the proprietor’s overflowing desk, unpacked cases, and a newspaper rack like one might expect to find in a café or coffeehouse. Intercepting her glance, Robillard chuckled. “Some men act, others think they could have done better than those who act. Though I am fascinated by mankind’s wicked ways, I am too fastidious to intervene. But”—he paused dramatically—“I forget my manners.” He tsked at himself. “Won’t you take a chair? I understand why Captain Fornier hides you from us, but I shan’t forgive him.”

Robillard’s excellent French explained his articulate servant but didn’t entirely restore Solange’s sense of order. She sank into his deep, too plush, too worn-out armchair.

When she declined a restorative, Monsieur Robillard said Nehemiah could brew tea, which she accepted, and Augustin left to set in motion.

Robillard fluttered his hands, mock ruefully. “Oh my, won’t Madame berate me for this!”

“For this, monsieur?”

“’Tis true. ’Tis true. Madame greatly overestimates my concupiscence. Madame has convinced herself no beautiful woman’s virtue is safe with me. And, madame, you would tempt a saint.”

These alarming words, uttered from such beaming complacency, made Solange smile. “I understand your wife’s concern, sir.”

“You do?”

“Were I not a wedded woman . . .”

He sighed. “Alas, so many women are. Or they are maids with fathers devoted to the Code Duello, or their brothers can shoot the pip out of a playing card, or those ladies have lovers, or are contemplating the wimple and habit; in Savannah society, madame, the aspiring rake is utterly hobbled and nobbled. The perfidious British understand these matters so much better than we French. Fais ce que tu voudras—Do what you will—and that sort of thing.”

“Shouldn’t my husband be in the room?” Solange said, feeling not the slightest concern.

Robillard took her hand. His palm was damp and earnest. “Oh, my dear, I am quite harmless. Though,” he added ruefully, “my Louisa doesn’t think so.” He clapped his hands. “That’s quite enough of me. In his absence—for he rejects every compliment—let me tell you how fortunate I am Captain Fornier has entered my service.”

He then offered the appraisal of her husband Solange had so hoped to create. Augustin was “Napoleon’s brave captain,” a “Hero of the Saint-Domingue Rebellion,” and “a true gentleman”—Solange’s smile faltered—“wise in the ways of the world.” Monsieur Robillard noted that he himself had had the very great honor of serving under the Emperor when he was merely Lieutenant Bonaparte many, many years ago. “We saw no fighting, alas.” His eyebrows climbed his forehead. “There was no fighting anywhere. Can you imagine?”

Ruth's Journey: The Authorized Novel of Mammy from Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Atria Books

- ISBN-10: 1451643543

- ISBN-13: 9781451643541