Excerpt

Excerpt

Robin

PUNKY AND LORD POSH

The house, on the northeast corner of Opdyke Road and Woodward Avenue, was unlike any other. The giant old mansion, nearly seventy years old, stood lovely and lopsided in its asymmetrical design, with its roofs and lofts of varying heights and chimneys that reached into the sky. Here in Bloomfield Hills, a wealthy northern suburb of Detroit where top executives of the automobile industry spent their evenings and weekends in rustic comfort with their wives, children, and servants, the unusual dwelling was more home than a family needed. It sat on a country estate that spanned some thirty acres of former farmland, with a gatehouse, gardens, barns, and a spacious garage that could hold more than two dozen cars. It even had its own name, Stonycroft, a harsh and daunting moniker for a tranquil, out-of-the-way setting. There were few neighbors for miles around and no distractions to disturb its residents from their serenity, aside from the occasional slicing at golf balls that could be heard from a nearby country club. More often, the chilly residence echoed with its own emptiness while its current tenants left many of its forty rooms mostly unoccupied, unheated, and unused. But on its highest floor, spanning the vast width of the house, was an attic. And in the attic there was a boy.

The sprawling manor was one of several places where Robin Williams had lived before he became a teenager, just the latest stop in an itinerant childhood spent shuttled between Michigan and Illinois as his father worked his way up the corporate ladder at the Ford Motor Company, and there would be more destinations on this lifelong tour, each of which would be his home for a time, but never for good. He and his parents would leave Stonycroft after a few years, but in a sense Robin would never leave its attic. It was his exclusive domain, where he was left by himself for hours at a time. Given this freedom, he shared the space with fictional friends he created in his mind; he made it the staging ground for the massive battles he would wage with his collection of toy soldiers, a battalion that ran thousands of men deep and for each of whom he had created a unique personality and voice. He used it as his private rehearsal space, where he taught himself to masterfully mimic the routines of favorite stand-up comedians he had preserved by holding a tape recorder up to his television set.

The attic was the playground of his mind, where he could stretch his imagination to its maximum dimensions. It was his sanctuary from the world and his vantage point above it—a place where he could observe and absorb it all, at a height where nobody could touch him. It was also a terribly lonely refuge, and its sense of solitude followed him beyond its walls. He emerged from the room with a sense of himself that, to outsiders, could seem inscrutable and upside down. In a room full of strangers, it compelled him to keep everyone entertained and happy, and it left him feeling utterly deserted in the company of the people who loved him most.

These fundamental attributes had been handed down to Robin by his parents long before the Williams family arrived at Stonycroft. His father, Rob, was a fastidious, plainspoken, and practical Midwesterner, a war hero who believed in the value of a hard day’s work. His approval, awarded fitfully and begrudgingly, would elude Robin well into his adulthood. His mother, Laurie, was in many ways her husband’s opposite: she was a lighthearted, fanciful, and free-spirited Southerner, adoring of Robin and attentive to him. But with her frivolity came unpredictability, and her affirmation, which was just as vital to Robin, could prove just as hard to come by.

On some level, Robin understood that he was the perfect blend of his parents, two drastically different people who, after earlier missteps, had found their lifelong matches in each another. As he later acknowledged, “The craziness comes from my mother. The discipline comes from my dad.”

But in the melding of their traits, behaviors, quirks, and shortcomings, they laid the foundation for a son whose life was filled with paradoxes and incongruities. As an adult, Robin would describe himself as having been an overweight child, only to have Laurie knock down this disparaging self-analysis, sometimes straight to his face and with photographic evidence to the contrary. He grew up aware of the luxury he was raised in, and even made humorous grist of it—“Daddy, Daddy, come upstairs,” he would later joke, “Biffy and Muffy aren’t happy. We have only seven servants. All the other families have ten”—yet when pressed on the subject, he could not always bring himself to admit his family was wealthy. He would describe himself as an only child, yet he had two half brothers, both of whom he loved and received as full siblings. He would call himself isolated, even though he had friends at every school he attended and in every city where he was raised.

For all the loneliness he experienced as a child, and the unsettled emotions that came from a youth spent in a state of perpetual transition—in an eight-year span, he attended six different schools—Robin concluded that his upbringing had been blithely uncomplicated. “It’s the contradiction of what people say about comedy and pain,” he would say many years later. “My childhood was really nice.” As he had spent his whole life learning, he could define himself however he wanted, picking and choosing the pieces of his history that he found useful while discarding the rest. Not all contradictions had to be detrimental. Some of them could even be productive.

In a portrait photograph of Rob and Laurie Williams taken early in their relationship, the two make for a deeply contrasting pair: “Picture George Burns and Gracie Allen looking like Alastair Cooke and Audrey Hepburn and that’s what my parents are like,” Robin later said. His father’s facial features are handsome but sharp, severe, and angular; he is clean-shaven and his dark hair is close-cropped and precisely set in place. His mother’s face is round, warm, and inviting, and even in this black-and-white image, the soft sparkle of her blue eyes is unmistakable. Her dimpled smile reveals a gleaming top row of teeth; his pleasant expression is thin and tight-lipped, giving away nothing. They are clasping each other, his arm wrapped around hers just below the lower border of the image, and for all that sets them apart, there is also plainly love between them.

Robert Fitz-Gerrell Williams, who was known as Rob, came from a background of privilege and had been taught the repeated lesson that adversity could be overcome through labor and perseverance. He was born in 1906 into a well-to-do family in Evansville, Indiana, where his father, Robert Ross Williams, owned strip mines and lumber companies. The younger Rob had a covert streak of playfulness, and he sometimes teasingly told people that his mother was an Indian princess. While he studied at prep school, his father would go on what Laurie would later describe as “periodic toots,” taking a suite at the Blackstone Hotel in Chicago where he’d grab a chorus girl or two and “just whoop it up.” Sometimes it fell to Rob, when he was as young as twelve, to travel the three hundred miles north to Chicago with the family’s black servant, get his father sober, and bring him home. Rob later enrolled at Kenyon College in Ohio, but when a stock market crash in 1926 nearly wiped out the Williams family business, he had to quit school, come back to Evansville, and take a job as a junior engineer in the mines. A few years later, when Robert Ross became gravely ill, Rob unquestioningly offered his blood for transfusions, until his father finally pulled the needle out of his own arm and told his son, “I don’t want you to do this anymore—you’ve done enough.” Robert Ross died a short time later.

Rob and his first wife, Susan Todd Laurent, had a son in 1938; they named him Robert Todd Williams, and he would be known as Todd. But by 1941, Rob and Susan had separated, and Susan took Todd to live with her in Kentucky. Rob was working for Ford as a plant manager when the United States entered into World War II, and he enlisted in the navy, eventually becoming a lieutenant commander on the USS Ticonderoga, an aircraft carrier in the Pacific. On January 21, 1945, while at sea near the Philippines, the Ticonderoga came under attack from Japanese kamikaze pilots, one of whom crashed through the carrier’s flight deck and managed to detonate a bomb in its hangar, destroying several stowed planes. More than one hundred sailors were killed or injured in the attack, and Rob was wounded when he leapt in front of his captain to protect him from an explosion, taking shrapnel in his back, legs, and arm.

Rob could not be redeployed in combat because of his injuries, so he reluctantly took a government desk job in Washington. But he soon returned to work at Ford, gaining a management position and eventually ascending to national sales for the company’s Lincoln Mercury division in Chicago. It was there in 1949 that Rob met an effervescent young divorcée named Laurie McLaurin Janin on a blind double date at an upscale restaurant. Laurie arrived with Rob’s receptionist while Rob showed up with the man who was supposed to be Laurie’s date, but it was very quickly clear that Rob and Laurie had eyes for each other. Rob told his receptionist to take some wild duck from the restaurant’s freezer and go home, while Laurie similarly dispatched her intended suitor. “I figured, hey, let the fun begin,” she said.

Laurie was attracted to Rob physically, drawn in by his confidence and captivated by his intense, understated charisma. As she described him:

He could walk in a room, anywhere, and the minute he walked in, people were at attention. We could go to any restaurant, anywhere, the finest. The maître d’ would come and up and say, “Sir, do you have a reservation?”

He would say very politely, “No, I don’t.”

“Right this way.”

“He definitely had ‘IT,’” Laurie said of Rob. “With a capital I and a capital T.” He also had a darker side that was activated by alcohol. When the couple miscommunicated over a canceled date and Rob thought he had been stood up, he was devastated. He told Laurie, “I went out and got so drunk.” She responded, “What are you talking about? You had drinks every night.” Perhaps the biggest fight they had, Laurie said, occurred when they were drinking at a restaurant and Rob leaned across the table to tell her: “You know what? My imagination is better than yours.”

“Oh man,” Laurie recalled. “The stuff hit the fan.”

Laurie was born in 1922 in Jackson, Mississippi, and raised in New Orleans, where she was immersed in the city’s epicurean culture and the lively parties thrown by her parents. Her parents’ marriage was mildly scandalous in the largely Catholic Crescent City: her father, Robert Armistead Janin, was Catholic, but her mother, Laura McLaurin, was Protestant. The couple had separated by the time their daughter was five years old and divorced soon after, leaving Laurie to live with her even more ostracized mother.

The McLaurin family was descended from the MacLaren clan of Scotland, and Laurie’s great-grandfather Anselm Joseph McLaurin had served as a captain in the Confederate army during the Civil War and was later elected a US senator and governor of Mississippi. But Laurie was essentially cut off from this aristocratic heritage when her mother remarried in 1929; her new husband, Robert Forest Smith, adopted Laurie and nicknamed her “Punky,” to her dismay. “Doors that would have been open to Laurie McLaurin Janin were slammed shut to Punky Smith,” said Laurie, who would nevertheless take ownership of the nickname and ask friends to call her Punky in her adult years.

Looking back on her childhood, she would recognize a strain of alcoholism that ran through her family, which made her mother volatile and her own life unstable. “Growing up,” Laurie said, “I never knew when I woke up each day whether I was going to be Queen of the May or Little Orphan Annie.” Her natural father, too, had a drinking problem: “It made me realize that we cannot drink,” she said. “There were people in the family who rose to great heights and then BOOM! just like that, and it was from alcohol. If you can’t handle it, just stay away from it.… It’s poison for our family.”

When the Great Depression nearly wiped out Robert Smith, it led to more than a decade of wandering for Laurie’s family, a time they spent shifting back and forth between New Orleans and Crowley, Louisiana. At one point, her stepfather considered running an ice-cream business, and, “for the first time in my life,” she said, “we didn’t have a colored servant. I thought that was the end.” In her late teens, she moved to Pass Christian, Mississippi, then back again to New Orleans, and in 1941 Laurie took up residence in a boarding house there while her parents went on to Mobile, Alabama. For a time she performed as an actress in the French Quarter. At the start of World War II, she was working for the Weather Bureau in New Orleans when the Pentagon inquired if she spoke French. “Fluently,” she lied, and she was transferred to an office in Georgetown. There in Washington she met a young naval officer named William Musgrave, and the two were married shortly before he shipped out to the South Pacific.

Now known as Laurie McLaurin Musgrave, she spent part of the war living in San Francisco, taking lithography classes and crossing paths (by her account) with the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright and Henry Miller. When the war ended and William Musgrave returned home, the couple lived briefly in San Diego and then moved to Chicago, where he found work as an electrical engineer. In 1947, Laurie gave birth to their son, Laurin McLaurin Musgrave, who would later be known as McLaurin. In his infancy, he developed pneumonia, and Laurie was fearful of the effects that a worsening Chicago winter might have on the child. So she sent the baby McLaurin to live with her mother and stepfather in Mobile. Laurie and William separated and divorced soon after. She was on her own, but she was unbowed and excited for all that lay ahead of her. “I just married too young,” Laurie would later explain. “I just thought I wanted to go out and try my wings.”

Two years later, Laurie was working as a model for the Marshall Field’s department store when she met Rob Williams, who touched her nonconformist’s heart to such a degree that she bought him an engagement ring and proposed that they get married. On June 3, 1950, they were wed by a justice of the peace in Omaha, Nebraska, and they took their honeymoon at a fishing lodge in Hayward, Wisconsin. Afterward, Laurie told Rob, “That was the lousiest honeymoon I ever had.”

The newlyweds moved into an apartment on Chicago’s north side, and on July 21, 1951, Laurie delivered their son, Robin McLaurin Williams, at Wesley Memorial Hospital. Though Robin would later joke that his mother’s concept of natural childbirth was “giving birth without makeup,” Laurie recalled his arrival as an easy one, nearly occurring in the hospital’s lobby. While the medical staff there peppered her with questions and requests for personal information, Rob scolded them: “Get this woman to a room. She’s going to have the baby right here.” As Laurie told the story, “They finally got me up to the room, gave me a shot, and, when I woke up, they said, ‘You have a wonderful baby boy.’ That was it.”

Unlike the difficulty Laurie had experienced following the birth of her son McLaurin, she had no such trouble with Robin, who was joyous and healthy, and who was raised principally by a black nurse named Susie. (Decades later, Laurie would still unhesitatingly describe Susie as “colored.”) “She wouldn’t put up with anything—wouldn’t take it,” Robin later said of Susie. “If you try and go, ‘I won’t do that.’ ‘Mm-hmm, I think you will. I think you’ll get your sweet self UPSTAIRS!’ She was a very strong force.”

Shortly after Robin’s birth, the family moved from Chicago to a rented house in Lake Forest, a suburb about thirty miles north of the city, beginning a migratory pattern for the Williamses that would persist for many years. Rob, an astute negotiator, would usually find the family’s homes, while Laurie was responsible for decorating and entertaining; these were crucial skills while Rob worked for Ford, which still considered itself a family business whose executives expected to be invited to frequent dinner parties.

After spending her days shopping and attending society luncheons, Laurie approached these formal, sit-down dinners as exciting opportunities to exercise her creativity. They required the careful planning of menus and seating charts, and the hiring of large numbers of household staff, including a seamstress who would sew fresh napkins and tablecloths for each gathering. Laurie was immersed in these events while Rob was consumed by his work; the family almost never took vacations, and the only indulgences Rob permitted himself were an occasional round of golf or a fishing trip. It seemed not to leave them very much time for child rearing at all.

Still, Robin grew up enthralled with his parents, captivated by their moods and desirous of their attention. In many family photographs from this period, his gentleness and humility radiate right off the page; he was a small boy, often with a crew cut, a ruddy complexion, his father’s pointed facial features and his mother’s iridescent blue eyes. (Aptly, one of his childhood nicknames was “Leprechaun.”) If Laurie is in the picture with him, she is usually beaming at her baby boy, mirroring his ear-to-ear smile as they share an embrace or, in at least one such photo, she faces off against him in a mock-combative pose while Robin, in a martial arts outfit, appears ready to deliver a devastating finishing move.

Robin was deeply enamored of Laurie, with her picaresque tales from New Orleans and unsqueamish sense of humor, exemplified by a beloved sight gag for which she would cut apart a rubber band, wad it up inside her nose, pretend to sneeze, and let it dangle flagrantly from her nostril. She also delighted in telling her son of a book, supposedly written by an English princess of the nineteenth century, about the many parties she had organized, titled Balls I Have Held. And she shared with Robin her affinity for strange poems that did not quite rhyme and which were not quite jokes, but which dared him to figure out the mystery of why they were funny. As one ran:

Spider crawling on the wall,

Ain’t you got no sense at all?

Don’t you know that wall’s been plastered?

Get off the wall, you little spider.

Another one went:

I love you in blue,

I love you in red,

But most of all,

I love you in blue.

Wherever their power came from, Robin understood that these verses could make his mother laugh, and he became determined to do the same. “At that point, I went, okay,” he said. “And then I tried to find things to make her laugh, doing voices or anything that would get a response out of her.”

“What drives you to perform is the need for that primal connection,” he later explained. “My mother was funny with me, and I started to be charming and funny for her, and I learned that by being entertaining, you make a connection with another person.”

But where Robin saw Laurie as a convivial and essentially optimistic figure—“my mother has never met a stranger,” he would later say—Rob was enigmatic and impenetrable. He regarded his father as ethical but stern, and the nicknames he had for Rob, like “Lord Stokesbury, Viceroy to India,” “Lord Posh,” or simply “the Pasha,” reflected his respect for his father and the authority he wielded, his aura of infallibility and the distance between them. Needless to say, Robin did not call his father these names to his face.

In one emblematic story from his upbringing, Robin recalled returning home from school with an envelope that he presented to his father. “What’s that, my boy?” Rob asked.

“My report card, sir,” Robin answered.

Rob opened the envelope and ran his eyes down a list of As, smiling as he reviewed the grades. “Well done, son,” he said. “Now let’s get ready for dinner.” Robin was eight years old.

As Todd, Rob’s older son, later described his father, Rob’s reticence obscured an ability to quietly scan a room, observe the people around him, and retain everything he heard them say. “It all went in and stayed there,” Todd said. “He never forgot anything anybody told him, unless, selectively, he did so.” Todd knew of one other person who shared this apparent modesty and also possessed this faculty: his half brother Robin. He “can be in a room full of people where there are ten conversations going on,” Todd said. “He will be talking to you and focused on you, but everything around him goes into that file.” It was a trait that Todd said Robin took with him into adulthood: “He’s very shy, very quiet. A lot of folks can’t believe that, but you have to recharge those batteries or you’re going to wind up in the loony bin.”

At a very early age, Robin noticed that alcohol could get his father to lower his protective shell. After “a couple of cocktails,” he later said of Rob, “he got very happy. He would just get very much, ‘What do you want, a car?’ I’m five.”

There was at least one other activity that could pierce Rob’s defenses and reach him at his soul, and one that he allowed Robin to share in. On those late weekday nights when Rob was looking for a way to unwind, he turned on Jack Paar’s Tonight Show. And when the droll, sophisticated host was joined by Jonathan Winters, the chubby-cheeked, rubber-faced deadpan comedian, Robin was allowed to stay up past his bedtime, join his father in the consoling glow of their black-and-white TV set, and watch Winters’s latest unpredictable routine.

In the first such appearance that Robin could remember, Winters came strolling onto Paar’s stage dressed in a pith helmet and declared himself a great white hunter. “I hunt mostly squirrels,” he said.

“How do you do that?” Paar asked.

Winters replied, “I aim for their little nuts.”

In a rare moment of father-and-son synchronicity, Rob and Robin burst out laughing. The effect on the child was galvanic: “My dad was a sweet man, but not an easy laugh,” Robin explained. “Seeing my father laugh like that made me think, ‘Who is this guy and what’s he on?’”

Robin said he was also watching Paar some months later when Winters gave his legendary performance in which the host offered him a stick (after slapping him on his shin with it) and Winters proceeded to fill the next four minutes relying solely on his improvisational instincts, metamorphosing from a fly fisherman to a circus animal trainer to an Austrian violinist; the stick became an oar in the grip of a chanting native canoeist, a spear in the chest of an unfortunate United Nations parliamentarian, and a golf club in the hands of Bing Crosby, whose trademark croon the showboating Winters could reproduce flawlessly.

Other TV comedians thrilled Robin, like Danny Kaye, the maestro of seemingly a million nonsense songs and a million more invented foreign accents. But no one lit him up quite like Winters, who concealed an impish sensibility in a seemingly button-down package. Winters did not apologize for his squareness, and instead made it a part of his stage persona. (“I like to fish, that’s one of my hobbies,” he joked. “The rest of them I can’t discuss.”) Also, like Rob, he had served in the Pacific during World War II. When Winters, a US Marine, returned from combat, he discovered his mother had given away his prized collection of toy trucks. “I didn’t think you were coming back,” she told him.

Unlike most stand-up comics, who wanted to stand out for having a particular persona, routine, or shtick, Winters was the rare performer who didn’t play by those rules. In Robin’s eyes, he was a master comedian who could make any stage his canvas, needing nothing more than a microphone and his boundless ingenuity. “He was performing comedic alchemy,” Robin said later. “The world was his laboratory.”

Before Bloomfield Hills and Stonycroft, the Williams family lived on Washington Road in Lake Forest, not far from Lake Michigan, in “a big house, in a neighborhood of fairly big houses,” said Jeff Hodgen, one of Robin’s school friends. “The house was set back, off a shared driveway from another road, so it was almost mysterious. You would walk through the trees and get to his house and go, ‘Wow—you live here?’”

Robin had the usual penchants for mischief. He became known around the neighborhood for possessing an enviable collection of toy soldiers—not the cheap plastic type, but the costlier kind made from metal—and for delighting in their destruction. “We’d go up on the garage roof with a book of matches and hold these soldiers over a match, and the lead would melt and drop off,” said Jon Welsh, a classmate. “I am amazed that neither one of us fell off the garage roof and broke an arm or a leg, or set the garage on fire.”

Other real-life implements of combat, like a silk parachute that his father had brought home as a war souvenir, became toys in Robin’s hands. “We’d take it out on the lawn and tunnel under it,” Welsh said. “And being silk, it would collapse around you. We would get in at opposite sides of the parachute and try to find each other, play games of tag or hide-and-seek. You couldn’t see underneath it, so you would be completely isolated. Anybody with claustrophobia would just freak out.”

In the presence of his parents, however, Robin suppressed his rebelliousness. “He always had an almost artificial, squared-up, shoulders-back thing” when Rob and Laurie were in the house, Welsh said. “It was ‘Yes, sir,’ and ‘Yes, ma’am.’ They weren’t martinets, as far as I saw. They were always very pleasant and social. But their rules in the house were, you call us sir and ma’am. And he was like, ‘Yes, sir,’ and ‘Yes, ma’am.’ Straight spine and shoulders back, son.”

Around the age of ten, Robin was introduced to his half brothers. Both had very different upbringings from his, and though their lives would intersect only intermittently, they would have a profound impact on Robin’s understanding of what constitutes a family. Todd, who was Rob’s older son, was now twenty-three years old and living in the Chicago area. He had grown up with his mother in Versailles, Kentucky, then ran away from home at the age of fifteen, making his way through Florida and working as a busboy in Naples. (“I was a dumb kid,” he later explained.) Todd’s rowdy streak did not dissipate after he returned to Versailles to finish high school, so he moved to Chicago to be nearer to his father and attend college at Lake Forest. It did not stick. “I played too much,” Todd said. “So much for higher education.”

Todd may have had a strained relationship with Rob, but he enjoyed an unexpected kinship with Laurie, his father’s new wife. “I was determined not to like her out of loyalty to my mom,” Todd said. “Laurie had married my dad and who did she think she was? But in a short period of time we became pretty good buddies.” When Todd misbehaved—which was often—Laurie looked after him. “I’d do something bad, Pop would be mad, and she would always manage to get in the middle and keep me out of too much trouble,” Todd said.

Todd believed he was held up to Robin as a living illustration of how he should not want to grow up. “He was reserved,” Todd said. “I was the other way and just full of hell. My father raised Robin saying, ‘Don’t do that. Your brother did that. See what happened to him?’”

But Todd became for Robin a model older sibling that he’d lacked until now, a rowdy harbinger of what adulthood might look like, as well as an occasional tormentor. As Robin recalled, “Todd always extorted all my money. He’d come into my room and say he needed some beer money, and I’d say, ‘Oh, gosh, yes, take it all.’ My mother would get furious, because Todd would get into my piggy bank and walk out with $40 worth of pennies.”

Meanwhile, McLaurin, who was Laurie’s older son, had been living in Alabama with Laurie’s mother and father, believing that they were his own parents. When Laurie would visit from time to time, they let him think that she was his cousin. However, when McLaurin was around thirteen or fourteen, they shared a startling truth with him: “They tell me that my very beautiful and drop-dead gorgeous cousin, Punky, is not my cousin,” he said. “She’s their daughter and my mother.” McLaurin could now decide whether he wished to live up north with Laurie, Rob, and Robin or to stay in Alabama and let his grandparents adopt him. Rob invited him to spend time with the Williams family while he weighed these options.

The discovery that he now had Robin in his life was one that McLaurin had longed for and welcomed wholeheartedly. Before this point, McLaurin said that he had been “growing up as a quote-unquote only child, and always hoping to have a brother. And then, all of a sudden—oh, boy, I do! I do have brothers, that’s wonderful. All our personalities seemed to blend very nicely together.”

McLaurin identified with Robin in a particular and meaningful way. “We were both very private, solitary-type individuals,” he said. “Both of us had this thing where we sometimes just liked to be in our own heads. And he was very much that way. He was a wonderfully kind, gentle, sweet soul.” He was also impressed with Robin’s vivid imagination, and how he expressed it through his collection of toy soldiers.

McLaurin admitted to some tensions with his mother, having been brought up by the same people who had raised her. But he was fascinated with Rob, who regaled him with stories about the reputed Chicago mobsters who would come to his old Lincoln dealership to buy their cars entirely in cash. “Two weeks later, they’d fish the car out of the river full of bullet holes,” Rob would claim. Where others regarded Rob as cold and uncommunicative, McLaurin was impressed with the tough but fair way he meted out his discipline. “He had a very strong personality and he would have his own way,” McLaurin said. “But if you messed up, the next day, you’d hear, ‘Well, bub.’ Uh-oh—okay, what did I do? And then he’d always explain the reason to you why this or that should have been done differently. He was a wonderful, wonderful gentleman.” In the end, McLaurin chose to remain in Alabama with his grandparents, who then legally adopted him. “It was kind of the devil you know versus the devil you don’t, as far as my decision to stay,” he explained. “But I deeply, deeply loved Rob.”

Todd and McLaurin met each other, too, and they and Robin all accepted one another as brothers. “It used to amaze Rob,” McLaurin recalled. “He said, ‘They all get along so well. I don’t understand it.’ I’d say, ‘Well, we didn’t grow up together—that’s why.’”

Yet it remained something of a bewilderment that, throughout his life, Robin seemed to acknowledge the existence of his siblings inconsistently. As Todd’s wife, Frankie Williams, said many years later, “Robin would say, occasionally, that he was brought up as an only child. And then, of course, we would have to deal with somebody saying, ‘Well, Todd, we heard that Robin’s an only child.’ And it’s like, no, he has two half brothers. And Todd would spend time with him and his dad and his stepmom, for holidays, summer vacations, that kind of thing.”

As an adolescent, Robin had little difficulty expressing his interest in girls—one that was happily matched by their interest in him—though his earliest relationships were largely chaste affairs. Christie Platt, a neighbor of his in Lake Forest, became one of his first girlfriends, when she was thirteen and he was twelve, and she remembered him as a conspicuously handsome boy. “I always thought he looked a little British,” she said. “He had that thatch of thick hair, and long legs and a husky little body.”

Their affection at this age was expressed by trading dog tags, “which was the thing to do,” Platt said with a laugh, “or you wrote the other person’s name all over your notebook. I’m pretty sure we never kissed each other or did anything like that. I think we just stood and talked shyly to each other and then went home.” On nights and weekends, they might ride their bikes together through the woods, or engage in Kick the Can or Capture the Flag with other friends. Occasionally she would see Robin playing with his toy soldiers with other boys, but she stayed out of such pastimes. “Those looked like very serious games,” she said. “They looked extremely boring to me.”

And then their brief entanglement unwound: Robin was a sixth grader at the Gorton School, but Christie, a year older, was a seventh grader at the Deer Path School, and knew she, a junior high student, risked social oblivion if she admitted to dating a younger, elementary school admirer. “I was kind of shy about it,” she said. “You’ve got people going, ‘I don’t know him. Does he go to Deer Path?’ And I’d go, ‘Welllll, he goes to Gorton.’ Try to make it sound cool. But it was completely uncool. There was nothing cool about that.”

While Robin was still in the fifth grade, his classmates started becoming targets for bullies, usually older children they encountered on the playground, although Robin himself proved more adept at escaping their attacks. His friend Jeff Hodgen recalled that “the bullies wanted to put me in my place, because I was as big as the sixth graders if not bigger, a lot of them. So they would actually hold me and hit me in the stomach, to knock the breath out of me. Robin was the one saying, ‘When the whistle blows, get back in the classroom.’ I think he was just being smart. ‘You want to avoid this pain? Get in quicker.’”

Between the fifth and sixth grades, friends saw a subtle difference in Robin. Hodgen said he noticed “just a year later, just the change in him, the maturity and the look on his face. He went from smiling and kind of shy in fifth grade, to almost—not a sneer, exactly. Almost like he’s ready to say something.”

As a seventh grader at Deer Path Middle School, Robin found it necessary to speak up, if only to save his own skin. “I started telling jokes in the seventh grade as a way to keep from getting the shit kicked out of me,” he said. By now, at school, many kids there “were bigger than me and wanted to prove they were bigger by throwing me into walls. There were a lot of burly farm kids and sons of auto-plant workers there, and I’d come to school looking for new entrances and thinking, if only I could come in through the roof. They’d nail me as soon as I got through the door.” Robin dismissed the notion that he might have been singled out because his family was wealthy. “How could they know I was rich?” he said. “Just because I’d say, ‘Hi, guys, any of you play lacrosse?’ They thought lacrosse was what you find in la church.”

But Robin did not have much time to hone his social skills. A few months into the school year, the Williams family was gone, having moved from Lake Forest to Bloomfield Hills. As best as Robin’s friends could tell, there was no forewarning that he was about to leave; one day, Jon Welsh said, “He just wasn’t in school. ‘Where’s Robin?’ ‘Oh, his family moved.’ He was just gone. You get used to it, because in that time, people did come and go, just like anyplace else.”

“He left without much of a ripple,” Christie Platt said.

Perhaps, wondered Welsh, the children of executives learn to be resigned about their transient way of life and avoid getting attached to their surroundings, just like army brats—“the kids who’ve been moved from one military post to another,” he said. “It’s sort of like an early intimation of death. Here today and gone tomorrow. We all internalize it, one way or another.”

In fact, Robin had been hurt by his family’s relocations, and had to train himself to be ready for whenever the next move might come. Each time he arrived in a new city or a new school, he felt awkwardly on display. “I was always the new boy,” he once said. “This makes you different.”

This latest move to Bloomfield Hills, and to the peculiar and secluded Stonycroft mansion, was particularly tough on Robin. It ushered in the beginning of a strange period spent partly in freedom and partly in banishment in the third-floor attic, searching for ways to stimulate his ravenous imagination. It wasn’t that he was unpopular with other kids in the neighborhood—“there were no other kids in the neighborhood,” he said. “I made up my own little friends. ‘Can I come out and play?’ ‘I don’t know; I’ll have to ask myself.’” He spent his time with Susie, the nurse and maid who had helped raise him as a baby back in Chicago and who continued to work for the Williams family at Stonycroft; with John and Johnnie Etchen, a black husband and wife who also worked as servants on the estate; and with their son Alfred, who was a few years older than Robin and would sometimes play with him there.

Robin endured long periods of heartache while Rob traveled for business or relaxation, and Laurie went with him, not appreciating how this detachment was affecting their son. “I didn’t realize how lonely Robin had been,” Laurie said many years later. “But I had to be with Rob. I didn’t trust him. Come on, don’t be stupid. But Robin suffered and I didn’t realize that. He had some very lonely years. You think you’re being a wonderful mother, but maybe you aren’t.”

Robin was not entirely alone in his upstairs exile. His inexhaustible collection of toy soldiers had made the move to Stonycroft with him, and now that he had vast new amounts of space in which to deploy them, and no one else to judge or dictate how they were to be used, his fantasy battles became more byzantine and ornate. In his third-floor hideaway, Confederate generals could take on GIs armed with automatic weapons, and knights on horseback could do battle with Nazis. “My world,” he said, “was bounded by thousands of toy soldiers with whom I would play out World War II battles. I had a whole panzer division, 150 tanks, and a board, 10 feet by 3 feet, that I covered with sand for Guadalcanal.”

He also found refuge in the routines of his favorite late-night comedians, which had become much more than a shared source of entertainment between his father and him. By holding a cassette recorder up to the television set, Robin had hit upon a rudimentary method to preserve these performances and make them portable. He diligently listened to these tapes, teaching himself to imitate the stand-up sets, paying close attention not only to their content but also to tone and tempo, to cadence and inflection. Comedy was a science to be studied, like chemistry; from some calculable combination of language and technique, an audience’s explosion into laughter could be guaranteed. If Robin had no one else to share these pleasures and insights with, he didn’t need them. “My imagination was my friend, my companion,” he said.

By day, Robin was enrolled in the Detroit Country Day School, an elite multicampus institution that had been founded in 1914. It was the most rigorous school he had attended to this point, with a dress code that required its students to wear sports coats, sweaters, ties, and slacks in the school’s navy and gold colors; it had an austere Latin motto, mens sana in corpore sano, meaning “a sound mind in a sound body.”

The school allowed only male pupils in its upper grades, which created some tensions for the postpubescent boys who roamed its halls. To placate the surging tides of testosterone, Robin said, “They’d bring in a busload from an all-girls’ school and dangle them in front of us at a dance. Then, just when you were asking, ‘Was that your tongue?,’ they’d pack the girls back up on the bus. I’d be chasing it, shouting, ‘Wait, come back—what are those things? What do you use them for?”

The school was engineered to groom its students for prestigious colleges and future leadership roles, and Robin thrived on the rigor. He even started carrying a briefcase to class. His grades were good and he blossomed as an athlete, trying his hand at football for about a week before turning to soccer and wrestling. With his dense, compact, and hairy body, Robin proved an especially proficient wrestler and went undefeated in his freshman year—until, by his own account, he reached Michigan’s state finals and was pitted against “some kid from upstate who looked like he was twenty-three and balding.”

A dislocated shoulder eventually required Robin to withdraw from the squad, but he came away transformed by the overall experience, having finally been allowed, as he put it, “the chance to take out your aggressions on somebody your own size.” He was also grateful for his interactions with the team’s coach, John Campbell, an outspoken iconoclast at Detroit Country Day who was also the chairman of its history department and adviser to its Model United Nations and Political Simulation teams. As his daughter Sue described him, John Campbell was an unapologetic liberal—“really idealistic, really left-leaning, really believed in democracy”—who loved to tangle with his students and force them to scrutinize their unexamined beliefs.

“Republicans especially,” Sue Campbell said. “A lot of his students were coming from families that were super-conservative and he just loved to needle them and challenge them. ‘Are those your views or your parents’ views?’” Though they might not manifest themselves in Robin right away, the values that Campbell espoused—and the confrontational manner in which he taught them—would reveal their impact in time.

At Detroit Country Day, Robin continued to slip one-liners into the otherwise sober speeches that students were required to give at lunchtime, a strategy that worked until he added a Polish joke into one such oration, to the displeasure of the school’s Polish American assistant headmaster. And it was where he—a not-especially-observant member of an Episcopalian family—attended as many as fourteen bar mitzvahs a year and made some of his first Jewish friends, whose funny customs and fatalistic attitudes would imprint themselves on his mind, and whose crackling, phlegm-filled Yiddish words, instantly hilarious in their enunciation, would live forever on his tongue. “My friends made me an honorary Jew,” he said later, “and used to tell people I went to services at Temple Beth Dublin.”

As he approached the end of his junior year at Detroit Country Day in the spring of 1968, Robin was flourishing. He was a member of the school’s honor roll; he had served on its Prefect Board, an elected student council; and he had been voted class president for the following senior year. “I was looking forward to a very straight existence and was planning to attend either a small college in the Midwest or, if I was lucky, an Ivy League school,” he recalled. But none of this would come to pass.

For many years, Rob Williams had prospered at Ford. He was a military veteran with a high school diploma who relished the chance to go toe-to-toe with a management staff that was increasingly younger, more educated, and less experienced than he was. As he once told his son Todd, “When I pull up to that building in the eastern suburbs and drive into the parking lot, I look up and I know there are fifteen young hotshot kids in there, all with MBAs, and they want my job. I’m the big boss. They know I don’t have a college degree and they really want to show me up. When I walk in the door, I take a big, deep breath of fresh air and it’s just like stepping into the Coliseum.”

But by the late 1960s, Rob could no longer fight this generational change in the company’s operations. As he saw it, Ford was ignoring his recommendations on its most prominent product lines, and it was time for him to leave. He parted ways with the company in 1967 at the age of sixty-one and took a pension; though Robin would later characterize his father’s departure from Ford as an early retirement, the arrangement, according to Laurie, did not allow her husband to collect the full benefits he would have received if he’d stayed on a few years longer. Rob wanted to move to Florida, but Laurie said she had no wish to live in “an elephants’ graveyard” with “a lot of old rich people.” Instead, she steered the family to California, and the town of Tiburon, on the San Francisco Bay. Rob accepted a job at First National Bank, a Detroit bank for which he was named western region representative.

Once more, Rob’s career choice was going to uproot the Williams family, and his decision would require that Robin leave behind the home and the school he had gotten to know, the friends he had made and the identity he had created for himself, to live in another part of the country that was thousands of miles away and utterly unknown to him. The relationships that Robin had started to develop here, the achievements he had earned, the coping mechanisms he had pieced together, and the sense of self-worth that had taken years to accumulate—all of that was gone, and he would have to rebuild them from scratch, as he’d done before, when they arrived on the West Coast. It was time to start all over again.

Copyright © 2018 by Dave Itzkoff

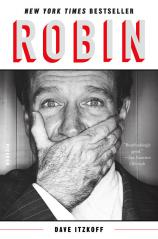

Robin

- Genres: Biography, Entertainment, Nonfiction

- paperback: 560 pages

- Publisher: Picador

- ISBN-10: 1250214815

- ISBN-13: 9781250214812