Excerpt

Excerpt

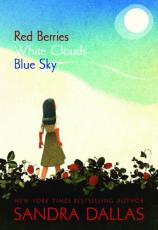

Red Berries, White Clouds, Blue Sky

1942 | CHAPTER ONE

THE SIGN ON THE DOOR

Tomistopped just outside the grocery store where her mother always shopped and peered through the glass in the door’s window. She loved the smells inside, of sawdust on the floor and of the bread that came in bright wrappers. Just beyond the door, she knew, were orderly displays of fresh fruit and vegetables—fat strawberries in green baskets, rows of corn covered by papery husks, cabbages as big as a baby’s head.

Most of all, Tomi loved the candy displayed in the big glass case. With a penny in her hand, she would choose from among the jumble of Tootsie Rolls, inky black licorice, and other sweets. Today, she thought, looking through the glass, she would pick two jawbreakers from a glass bowl. The jawbreakers were two for a penny, which meant she and her brother Hiro could each have one.

She pushed the door open and heard the jingle of the bell that announced customers entering the store. But just before she stepped onto the old wooden floor, she spotted a sign taped to the window. Her mouth dropped open, and she stopped so abruptly that Hiro ran into her.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

Tomi turned around. “I left the penny at school,” she said.

“It’s in your hand,” he told her.

Tomi looked down at her fingers, which clutched the coin. “We’re not going in there.”

“Why not?” Hiro asked.

Tomi took her brother’s hand and tried to pull him away, but Hiro refused to move. Then he spied the sign on the door. “What’s that sign say?” he asked.

“I can’t read it,” Tomi said quickly.

“You’re twelve, and you can so read it. I’m seven, and I can read, too.” He squinted as he sounded out the words. Then he looked up at his sister. “It says ‘No Japs.’ That’s not a very nice word, is it?”

Tomi shook her head and tugged at her brother.

“Mom says the word is ‘Japanese.’ ‘Jap’ is a mean word,” Hiro said. He read the sign again, then grinned. “It’s okay, Tomi. We’re not Japanese. We’re Americans. We can go in.”

Just then, a man in a white apron came to the door and stared at Tomi and Hiro.

“Hi, Mr. Akron,” Hiro said. He and Tomi had bought candy from Mr. Akron ever since they could remember.

Mr. Akron looked uncomfortable. He made a shooing motion with his hand. “Go on, kids. Scram. Can’t you read the sign?” He wiped his hands on his apron.

Tomi stared at him a moment, then said, “Come on, Hiro. Let’s go. They don’t want us here. Besides, who cares about that old candy anyway?” She looked at the ground instead of at her brother or the grocer. Her face was red as she stared at the sidewalk, wishing her mother had never given her the penny. She wanted to be anywhere but in front of the store where the man thought she was a Jap.

“How come we can’t come in?” Hiro asked.

The grocer ran his finger around the inside of his collar. “You Japs bombed Pearl Harbor,” he said, then turned and went inside, closing the door.

“Me and Tomi didn’t bomb anybody,” Hiro called through the glass, but Mr. Akron ignored him.

“Come on, Hiro!” Tomi yanked her brother along the sidewalk. She walked with her head down. Her hair hid her face; she hoped nobody would recognize her. She had never been so embarrassed in her life.

“I don’t understand. What’s Pearl Harbor?” Hiro asked, stumbling along beside his sister. “Why won’t he sell us candy?”

Tomi turned the corner and headed toward a park. It was the long way home, but they weren’t likely to run into any kids they knew, and that was good. She didn’t want anyone to find out what had just happened.

They reached a bench, and Tomi sat down, Hiro next to her.

“What’s Pearl Harbor?” Hiro asked again.

Tomi took a deep breath. “It’s a place in Hawaii. The Japanese bombed our American ships there, and lots of sailors were killed.”

“Jeepers!” Hiro tried to whistle through his teeth, but his front teeth were missing, so the sound came out like a rush of wind. “How come they did that?”

Tomi shook her head. “I don’t know. I heard it on the radio, and I heard Mom and Pop talk about it, but they stopped when they found out I was listening. So I don’t understand everything. I just know President Roosevelt declared war on Japan.”

“But why won’t Mr. Akron let us into his store?”

“I guess he thinks we’re spies or something, you know, like they talk about on the radio.”

Hiro thought that over, then asked, “Spies? Who are we supposed to spy for?”

“Japan,” Tomi answered.

“But we’ve never been there. Heck, Tomi, we don’t even speak Japanese.”

“Mom and Pop both came from Japan, and our grandparents Jiji and Baba still live there.”

“We don’t even know them,” Hiro said.

Tomi shrugged. “I don’t understand it, either. We say the Pledge of Allegiance every day in school, and we salute the flag. Pop always told us he and Mom were the best Americans because they chose to live in this country; they chose for you and me and Roy to be born here.” Roy, their older brother, was almost sixteen.

“Are we going to tell Mom about the sign?” Hiro asked.

Tomi looked down at Hiro. “I don’t know. Maybe we should so that she doesn’t shop there.” Tomi didn’t like the idea that Mr. Akron might be rude to her mother.

The two of them sat on the bench, not talking for a few minutes. It was winter, and although snow didn’t fall in their southern California town not far from the ocean, the weather was cold. Tomi felt the chill and shivered. She started to tuck her hands into the sleeves of her sweater, then realized she was still holding the penny. “Those jawbreakers would probably break our teeth. I don’t want one anyway,” she told her brother.

“Me neither,” Hiro said. He grinned, and Tomi punched his arm.

“Besides, you don’t have enough teeth to chew one,” she said.

1942 | CHAPTER TWO

POP AND THE FBI

Tomi loved their little farmhouse. It was painted yellow, the color of the sun, Tomi’s favorite color. An American flag hung from a pole in the yard. Pop raised it every day, while Tomi, Hiro, and Roy stood beside him. Then he lowered it at night, choosing one of the children to help him fold it. The flag was kept in a carved box next to the front door. Tomi was proud when she saw the red, white, and blue flag flying from its pole in front of the house.

Pop grew strawberries that were even bigger and redder than the ones in Mr. Akron’s store. Pop didn’t own the farm. He had come to America from Japan when he was younger. He told his children since he was born in Japan, he was an Issei, or first-generation American. The law said Issei couldn’t own land in America. Pop’s real name was Osamu, but everybody called him Sam. Mom, whose name was Sumiko, was an Issei, too. Tomi and her brothers, Hiro and Roy, were born in America. Pop explained that they were Nisei, or second-generation Americans.

It didn’t matter that Pop just rented the farm, however. He had worked it since before Tomi was born, and the farm was the only home she’d ever known. Pop rented the land from Mr. Lawrence, who lived a mile away in a big house with white pillars in front. His daughter, Martha, was Tomi’s best friend. They played together all the time in Martha’s big house or in Tomi’s tiny yellow cottage.

Mr. Lawrence’s brand new Ford motor car was parked in front of the Itano house along with a car Tomi didn’t recognize. Mr. Lawrence believed in Ford cars and bought one every two years. He’d encouraged Pop to buy a used Ford truck the year before. Pop had never owned a truck, and he was proud of it. He and Roy washed it every Saturday.

Mr. Lawrence stood on the porch with a man in a suit and hat. The two of them were hidden behind a trumpet vine and didn’t see Tomi and Hiro as they came down the road.

“Sam Itano’s as good an American as I am,” Tomi heard Mr. Lawrence say. His voice was loud and angry.

“Then why did he buy so much fertilizer? And gasoline, too? I’m betting it’s for the Japanese submarines. They’ve been spotted off the coast.” The second man didn’t look much older than Roy.

“Look around you. This is a farm. You need gasoline to run the equipment. Sam’s a smart farmer. He’s stocking up on gas before it gets scarce. Besides, submarines don’t run on gasoline,” Mr. Lawrence told him.

“That’s beside the point,” the man wearing the suit said.

“Then what is the point?” Mr. Lawrence asked.

“Sam Itano’s a Jap.”

“Around here, we call him a Japanese,” Mr. Lawrence said.

A third man came out of the house. He had Pop’s newspaper in his hand and held it high so the others could see. “Look at this. It’s in Japanese.”

“That’s Sam’s newspaper. Are you saying it’s illegal to read a newspaper written in another language?” Mr. Lawrence asked.

“It is if it’s subversive.”

“What’s subversive?” Hiro asked. His voice carried. Tomi whispered, “I think it means ‘doing something against the government.’ ”

The men on the porch hadn’t noticed the two children until now. One asked if they were the Itano kids. When Tomi nodded, he asked, “Your dad have a radio?”

Tomi didn’t like the way the man sounded. Is there something wrong with having a radio? she wondered. She was about to tell them she didn’t know. But Hiro belted out, “You bet! It’s a Philco, brand-new. We got it for Christmas. It’s swell.”

The two men looked at each other. “And he listens to it, does he? What does he listen to?”

“Oh, everything,” Hiro said, before Tomi could stop him. “He listens to Blondie and Fibber McGee and Molly. And when he’s not home, Mom listens to Backstage Wife and Our Gal Sunday. Pop says they’re dumb.”

“They’re soap operas,” Tomi explained.

“I bet he listens to Japanese programs, too, doesn’t he?” one of the men asked.

“There aren’t any Japanese programs on the radio,” Tomi told him.

The two men looked at each other, while Mr. Lawrence muttered, “Ha!” Pop came out of the house then and motioned for Tomi and Hiro to go to him. Tomi wondered where Mom was; probably working in the strawberry fields. Pop was sweating, and he had a worried look on his face. He jingled the coins in his pocket. He did that when he was nervous. The day Pop arrived in America, he found a silver dollar on the street. It was his lucky coin, and he always carried it. Now he thumped the small coins in his pocket against the big silver dollar.

Tomi asked Pop about the two men, and he whispered, “They’re from the FBI.”

“Wow! The FBI, like in the movies!” Hiro said. “Are you going to help them capture some bad guys, Pop?”

Tomi knew the FBI agents weren’t there to ask for Pop’s help.

One of the men asked Tomi, “Does your father use the radio late at night?”

“Sure, he listens to One Man’s Family,” Tomi said.

The agent looked annoyed. “Does he use it to talk to the Japs?”

“Japanese.” Mr. Lawrence reminded him.

Hiro laughed. “Boy, is he dumb. You don’t talk to a radio,” he whispered. “Keep still, boy,” the agent who’d come out of the house said. He turned to the other man. “You should see what he’s got in there—Japanese books, letters, even a picture of the Emperor. We better take him in.”

Mr. Lawrence stepped between Pop and the men. “On what grounds?” he asked.

“Espionage,” the FBI man said.

“That’s spying,” Tomi told Hiro before he could ask.

Pop glanced from the two agents to Mr. Lawrence. “How can that be? I’m an American.”

“You’re not a citizen, are you?”

“I can’t be. The law doesn’t let Issei become citizens,” Pop explained.

“You had a camera. What were you taking pictures of?” The agent was holding Pop’s camera in his hand, the back of it open.

“My strawberry plants. And my children. You’d see if you hadn’t exposed the film.”

“Oh yeah?” The man took out a pair of handcuffs and motioned for Pop to put his wrists together in front of his waist. As the men led him to their car, Pop wouldn’t look back at Tomi and Hiro. It was hard for Tomi to look at him, too. “You kids tell your mother I’ll be back later to explain what’s going on,” Mr. Lawrence said. Then he turned to Pop. “Don’t worry, Sam. This isn’t right. I’ll get a lawyer for you. He’ll prove you’re a good American and shouldn’t be arrested.”

“Don’t bother,” one of the FBI men said. “It won’t do him any good.” Then he turned to Tomi and Hiro and said, “You kids, you tell your mother you’re not to go more than five miles from here. And there’s a curfew. That means you’re not to be out after dark.”

★

Mom had been working with the strawberry plants and hadn’t known what had just happened. After all, people were always stopping by to buy strawberries. Pop always talked to them, because Mom was shy around strangers. As soon as Mr. Lawrence drove off, Tomi and Hiro ran to her, careful not to step on the strawberry plants.

“The FBI took Pop away. They put handcuffs on him,” Hiro called to her.

“What?” Mom had been stooped over the plants, and she looked up, then rose slowly. “They called him un-American,” Tomi said. “I’m scared, but Mr. Lawrence said not to worry, that he’d get a lawyer to help Pop.”

Mom put her hands over her face and stood that way for a long time. “I told him to get rid of those letters, those newspapers,” she said to herself. She took her children’s hands, and they walked back to the house.

When they went inside, Mom gasped at the mess the FBI agents had left. She always kept the house tidy. But now, drawers were pulled out in the bedroom and clothes dumped onto the floor. Dishes and canned goods had been taken from kitchen shelves and set on the table. The back of the radio had been pried off. Pop’s letters from Jiji and Baba in Japan were scattered about. “Oh,” Mom said, and sat down in a chair.

Tomi offered to put things away, but her mother said no. “We’ll burn all this. I told your father to do that, but he said that everything would be all right.”

Tomi and Hiro gathered up the papers that had been thrown onto the floor and put them into the stove. Mom picked up the picture of the Japanese emperor and placed it on top of the papers. Then she went into her bedroom and took down a wall scroll with a picture of a Japanese mountain on it and added it. Finally, she went to the closet for her best kimono. It was a beautiful turquoise silk dress she wore on special occasions. She shoved it into the stove. She cried when she lit a match and watched the silk catch fire. “We have to get rid of everything Japanese so that we can show we aren’t aiding the enemy,” she said.

“What about my doll?” Tomi asked. Her grandparents had sent her a Japanese doll with long black hair and bangs just like Tomi’s. Her name was Janice. Tomi was too old to play with dolls, but she loved Janice too much to give her up.

Mom shook her head. “Surely, they can’t object to a doll.”

Tomi and Hiro sat beside their mother and watched as the fire burned. “I don’t understand,” Hiro said at last. “What did Pop do?”

“Nothing,” Mom replied. “He didn’t do anything. It’s because he’s Japanese.”

“No he’s not. He’s an American,” Hiro insisted.

Mom nodded, and then she asked Tomi to fix tea.

Tomi filled the kettle with water and placed it on the stove. She let the water boil, then set it aside a minute to cool before she poured it over the tea leaves in the teapot. The finest tea, Tomi knew, required hot, not boiling, water. After letting the tea steep, she poured it into blue-and-white china cups, each with a different design. Tomi picked up her mother’s cup and handed it to her, wondering if they would have to get rid of the tea set.

Mom carried the tea to the table, and Tomi and Hiro sat down on either side of her. Hiro gulped his drink, but Tomi held her cup in her hand, letting the warmth rise and fill her nose with the sweet smell of tea.

“As you know, your father came to America from Japan when he was eighteen years old,” Mom began. Tomi and Hiro had heard that story many times, but Mom always started at the beginning, and so she repeated how Pop had come to the United States because he thought there were more opportunities here for a boy like him. Pop got a job on a farm, laboring long hours at back-breaking work. He believed that was the way to get ahead. He saved his money and rented a few acres of farmland, where he grew strawberries.

The farm was successful. So he sent to Japan for a “picture bride.” Picture brides were Japanese girls who wanted to marry Japanese men living in America. They sent their photographs to what was called a marriage broker. Pop chose Sumiko. She wasn’t the prettiest of the girls whose pictures he studied, but she looked like the sweetest. Sam thought she would be a worker, too. So he paid her way to America, and they were married.

They were a good match. Sam and Sumiko cared about each other just as much as any American couple who had married for love. Many times, Tomi had seen her father take the picture bride photograph out of his wallet and smile at it.

“Your pop wanted us all to be Americans. That’s why we speak English at home and wear American clothes. America’s made up of people from all over the world,” Mom said. She reminded Tomi and Hiro that the immigrants were Americans now, but they hadn’t forgotten their foreign cultures. That was why the Mexicans in California ate tortillas and chili and sang beautiful songs in Spanish and the Germans held a harvest festival where they served beer and bratwurst. The Japanese weren’t any different. Mom fixed spaghetti and tuna fish casseroles along with Japanese food and dressed just like other women in California, wearing a kimono only on special occasions.

Tomi knew all that, and she squiggled in her chair, wishing her mother would get on with it.

Finally, Mom did. “Everything was all right until Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor last December and America declared war on Japan. Some Caucasians—white people—think we’re spies just because we came from Japan. They believe we’ll help the Japanese invade America.”

“Invade means land here,” Tomi explained to Hiro.

“I already know that,” he said.

“These people think we’re loyal to Japan instead of America,” Mom continued.

“But can’t they see our flag?” Hiro asked. “And don’t they know we say the Pledge of Allegiance and Pop decorated his truck with red, white, and blue crepe paper for the Fourth of July parade?”

Mom looked down. “They say it doesn’t matter, that we’re only trying to trick them into believing we’re loyal.”

“Why would they take Pop?” Hiro asked.

Mom shook her head. “This is war. People are scared.”

“They’re scared of us?” Tomi looked at her brother, then at her mother, who wasn’t much taller than Hiro. Tomi glanced at her reflection in the mirror across from the table. How could anyone be afraid of her? “Shikata ga nai,” Mom said. That was her favorite expression. Of course, it was a Japanese expression, but there was no reason it couldn’t be used in America. It meant “It cannot be helped.”

1942 | CHAPTER THREE

THE END OFSCOUTING

Roy burst through the door and threw his clarinet case onto a chair. Tomi’s brother was in the school orchestra, and he and four other boys had their own band called the Jivin’ Five. They played at school and church dances. “I ran into Mr. Lawrence down the road. He told me the FBI arrested Pop. What happened?”

“They think he’s a spy,” Hiro replied.

“They think we’re all spies,” Tomi added.

“For growing strawberries?”

“For being Japanese,” Mom said.

Roy sat down and put his head in his hands. “I guess I shouldn’t be surprised,” he said. “Last week, a woman asked about hiring the Jivin’ Five to play for a party, but she said she didn’t want me there.” The other members of the band were Caucasians.

“Jivin’ Four doesn’t sound like much,” Tomi said.

“I guess we just have to wait until people figure out we’re not the enemy.”

★

But some people insisted the Itanos were the enemy.

A few days later, Tomi went to her friend Mary Jane Malkin’s house for her weekly Girl Scout meeting. Tomi loved scouting. The members of her troop were her best friends. They had come to the Itano place in the fall to work on their merit badges for gardening. Pop had showed them how he planted the strawberries and cared for them. He’d let the scouts have a piece of land for their own garden. All the girls had gotten their gardening badges. Tomi had been the first. She worked hard to earn badges and had more than anyone else in her troop. And she’d sold more Girl Scout Cookies than any of the other scouts, too. Tomi liked to think up projects for her troop, and when war was declared, she’d suggested they learn to knit and make socks for the soldiers. All the girls went to the Itano house to learn knitting from Mom, who was good at knitting and sewing. Tomi wanted Mom to be a scout leader, but Mom was too shy.

Tomi was proud of her green uniform and yellow scarf. She ironed it every week so that it was fresh for the after-school meeting. She and Martha always walked to the Malkin house together on Girl Scout days.

As they reached the porch, Mrs. Malkin came outside and stood in front of the screen door, blocking their way. Mary Jane was beside her. “Go on in, Martha,” she said.

Martha paused a moment, looking at Tomi, but Mrs. Malkin opened the door. “I told you to go inside, Martha.”

Martha glanced at Tomi and did as she was told, but she stood just inside the screen. Tomi started to follow, but Mrs. Malkin put her hand on the door and held it closed. “I’m sorry, Tomi, but you’re not welcome here anymore.”

Tomi didn’t understand. She tried to recall if she had done something wrong. Maybe she’d forgotten to wear her uniform or she’d failed to complete the work for a merit badge, but those things wouldn’t have kept her from attending a meeting. She turned to Mary Jane, who was standing next to her mother, but her friend wouldn’t look at her. Instead, Mary Jane rubbed the toe of her shoe back and forth on the porch floor. “Why? What did I do?” Tomi asked.

Mrs. Malkin looked uncomfortable then. “It’s best that you not be a scout anymore. I’m sorry.” She didn’t sound sorry to Tomi.

“Why? Why can’t I be a scout anymore?”

“This is an American troop.”

Tomi looked at Mrs. Malkin. “I’m an American. I was born right here in California, before you moved here from Ohio.”

“We don’t allow Japs in this house,” Tomi heard Mr. Malkin say. She’d never liked him much. He expected Pop to give him a discount on strawberries, and whenever the scouts had a family potluck, he took more than his share of Mom’s Japanese food.

“Don’t be difficult, Tomi. That’s the way things are,” Mrs. Malkin told her.

“That’s not fair,” Martha said through the screen. “Tomi can’t help who she is. She’s the best scout in the whole troop. You can’t ask her to leave.”

Mrs. Malkin looked back at Martha. “Be still. This does not concern you, Martha. You’re too young to understand.”

“I do so understand. Maybe I don’t want to be a scout if Tomi can’t. Come on, Tomi, let’s go home.”

Tomi shook her head. If Martha quit, that would only make things worse. Tomi heard the other scouts whispering behind the door and knew they would blame Tomi. They would tell everyone at school that Martha’s leaving was Tomi’s fault. “No, you stay,” Tomi whispered. She turned quickly, so that no one would see the tears in her eyes. She wished she were so small she could disappear. She wouldn’t run, though. Instead, she forced herself to walk at a normal pace until she turned the corner and was out of sight. Then when no one could see her, Tomi broke into a run and didn’t stop until she reached home. There she ripped off her yellow Girl Scout scarf and threw it into the stove.

The next week on Girl Scout day, Tomi wore a regular dress. Mom didn’t ask why. She knew.

★

Although Mr. Lawrence talked to a lawyer, there wasn’t anything that could be done about Pop. The lawyer explained that the government had passed wartime laws that allowed it to keep men in prison when they were only suspected of being spies. There didn’t have to be proof.

A few weeks after Pop was taken away, Mom received a letter from him, saying he had been sent to New Mexico. There were no details, because most of the letter was blacked out. There wasn’t even a return address, so Mom couldn’t write him—or visit him. But they couldn’t have done that anyway, because they had been told they couldn’t go more than five miles from their home. And they weren’t allowed to be out after dark, either.

By then, the government was asking all Japanese living on the West Coast to move away from the ocean—to Montana and Colorado and Kansas, where they would be too far away to contact the Japanese enemy. Mom refused. How would Pop ever find them if they left California? she asked. Besides, they couldn’t just walk away from the farm Pop had worked so hard to make successful. Roy volunteered to quit school so that he could take Pop’s place with the strawberries, but Mom wouldn’t let him. “Pop wants you to finish high school, because he didn’t have that opportunity in Japan,” she told him.

Even if Roy had quit school, it wouldn’t have made a difference, because in February, just two months after Pearl Harbor was bombed, the government issued Executive Order 9066. The order allowed the government to round up all Japanese people living on the West Coast and send them to ten “relocation camps” in California, the mountain states, and Arkansas. Roy scoffed at that. “Relocation, heck! They’re sending us to prison.”

Red Berries, White Clouds, Blue Sky

- Genres: Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 216 pages

- Publisher: Sleeping Bear Press

- ISBN-10: 1585369063

- ISBN-13: 9781585369065