Excerpt

Excerpt

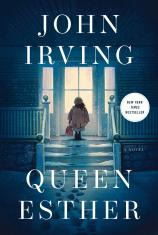

Queen Esther

1. The Townspeople of Pennacook

A Josiah Winslow was born in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1629—his father, Edward Winslow, was a Separatist Puritan who’d traveled on the Mayflower in 1620. Edward’s younger brother John sailed on the Fortune, arriving in Plymouth in 1621. Beginning in Puritan times, more Winslows kept coming.

The present-day James Winslow, who was called Jimmy as a child, was unimpressed by his Winslow ancestry—he’d learned not to care who his ancestors were. “When it comes to your forebears, you deserve no credit, you should take no blame—you don’t get to pick your parents, do you?” Jimmy’s grandfather, an English teacher, had told him.

James Winslow would be a student abroad for only one year, yet what happened to him in a foreign country confirmed his belief in his intrinsic foreignness. It seemed a contradiction that Jimmy Winslow would always say he was just a New Hampshire boy. He wasn’t New Hampshire enough for the townspeople of Pennacook; the townsfolk had made it their business to know where the Winslows came from.

If you grew up in Pennacook, in southeastern New Hampshire, in the 1940s and 1950s, where you came from mattered. You knew there was a class system in America; you were aware of a ruling class, and you sensed your place in society. The town is situated around the falls where the freshwater Pennacook River meets the tidal, saltwater Squamscott—once the land of the Squamscott Native Americans, a subtribe of the Pennacook Nation. The name Pennacook comes from the Abenaki word penakuk, meaning “at the bottom of the hill.” The town’s founder had left England to escape religious persecution; he’d also been exiled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for sharing his sister-in-law’s dissident religious views. The English Puritans bought the land from a Squamscott sagamore. There were similar small towns throughout New England—factory towns or mill towns, where your social standing was clear. Class consciousness wasn’t unique to Pennacook, where there was a textile mill (as long ago as 1830) and a shoe factory (since 1884). What set Pennacook apart, and gave the town an acute class consciousness, was a private school for boys.

Established in 1781, Pennacook Academy was an independent school for boarding and day students, ninth grade to twelfth. The academy was one of the oldest secondary schools in the United States. In the 1950s and 1960s, when James Winslow was a student there, he was aware that his social standing at the academy wasn’t evaluated by his fellow students in the same way it was by the town.

In the 1950s and 1960s, unlike the town, Pennacook Academy was a meritocracy; the school cared if you were good in the classroom. To the academy, your grades mattered—to the boys, not so much. Your wit was what mattered to the boys; they cared if you could entertain them. You were forgiven for not being entertaining only if you were a jock. To Jimmy Winslow, the way he was evaluated at school made more sense than the scrutiny he withstood in town.

What did the Mayflower matter to those Pennacook Academy boys? Their class consciousness wasn’t aroused by America’s first settlers—least of all, by the ship they sailed on. The day boys distrusted the boarders and vice versa. In an international school, nothing is universally true, but the boarding students were generally more worldly; in comparison, the townies seemed unsophisticated.

James Winslow was distrusted by both the day boys and the boarders, because he was in a subclass of townies. Faculty children were in a difficult position, but Jimmy Winslow was an unusual faculty brat. He was the grandson of the most revered member of Pennacook’s English Department. Thomas Winslow was the most popular teacher at the academy; his students adored him. You might suppose, then, that James Winslow would have been trusted by his fellow students and welcomed by the faculty, above all the other boys—but he wasn’t a real Winslow. Jimmy was a nobody’s boy. This much was understood: his mother had adopted him; his father was an unknown. As for the boy’s birth mother, she put no one at ease. For starters, she was an orphan.

To the townspeople of Pennacook, James Winslow was (and would always be) the orphan’s kid. The academy was kinder. To the students and faculty alike, maybe Jimmy wasn’t a real Winslow, but there were a whole lot of Winslows and they all loved and looked after that boy. (Well, no wonder, the townspeople of Pennacook pointed out—Jimmy was the only Winslow boy.)

Years later, whenever James Winslow was being modest, or he was otherwise at a loss for words—and he always spoke excruciatingly slowly—he would repeat he was just a New Hampshire boy. Naturally, the townspeople of Pennacook thought they knew better; the Winslows weren’t like the rest of the locals, the orphan’s kid included. For all their meddlesomeness, what the townspeople of Pennacook actually knew amounted to only this. The circumstances of James Winslow’s birth were fraught with irregularities. When babies are born and transferred in such a way that you don’t even know whose babies they are—not exactly—aren’t things bound to go off the rails in a family? The townspeople of Pennacook were poised for things to go awry with the Winslows—with that adopted boy, especially. Maybe then those Winslows wouldn’t seem so proud. The townspeople of Pennacook were sick and tired of the respect shown those Winslows as a model family, even when it came to their adopting an orphan’s child.

Queen Esther

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 432 pages

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- ISBN-10: 1501189441

- ISBN-13: 9781501189449