Excerpt

Excerpt

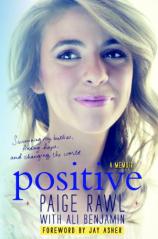

Positive: A Memoir

Preface

Nobody quite prepares you for the moment you see your own name scrawled on a bathroom wall.

To be honest, until I saw my own name, it never really occurred to me that all those names I’d seen before—all those names that appeared on the restroom walls of Dunkin’ Donuts and 7-Elevens, the Castleton Square Mall and the corner gas station—represented actual human beings.

If I ever bothered to wonder about those people, even briefly—Will Jasmyn actually love Shawn 4ever? What happened to Darren that we should never, ever forget him?—the moment surely would have passed long before I washed my hands and placed them beneath the whirring hand dryer.

Then one day, I walked into a bathroom in my middle school, and there was my name in thick black marker. Beneath it, other kids had added their own words in ball-point pen.

I never in a million years expected to see my name on this wall. I’d always considered myself a good girl—more Glee than Kardashians, more Taylor Swift than Miley Cyrus. I was born a joiner, not a fighter.

But I was beginning to realize that sometimes a person doesn’t get to choose whether she joins or fights. Sometimes the joining is impossible, sometimes the fight chooses you. The universe plucks you—you, specifically—out of all those souls out there and hands you something that makes fitting in and going with the flow utterly out of the question.

“I’m sorry,” the universe says. “I’m afraid you’re going to have to fight.”

And when you stare back at the universe, not understanding, it simply shrugs. “You’d better start now. Or this world will destroy you.”

I didn’t have a choice: I had to learn to fight.

As my story unfolded over the next few years, I’d learn some things. I’d learn that you can fight with a smile. That you can fight in a dress, or a cheerleader’s skirt, pom-poms in hand. You can even fight just by wearing a sparkling tiara and a satin sash that says miss indiana high school america.

But I hadn’t figured those things out just yet. All I knew, standing in the girls’ room, was that everything I knew, everything I had planned for myself, was changing.

I stared at the writing and considered my options.

I could scribble it all out, just try to erase the whole thing. Unfortunately, the only writing utensil in my purse was a pen. It might cross out those added comments, but it would never, ever cover that fat black marker.

Besides, crossing out the words wouldn’t stop people from thinking things about me. It wouldn’t change anyone’s mind.

There was nothing to do. Nothing to do but look in the mirror and smooth down my hair, take a deep breath, and push the door open. By the time I stepped into the hallway I was smiling, as if I hadn’t seen a thing, as if all was exactly as it should be. As if that felt-tipped warning to all the other kids, that I didn’t belong—that I was to be shamed and shunned—never existed.

PAIGE HAS AIDS, it read.

Then underneath—Slut. Whore.

And finally, PAIGE=PAIDS.

Actually, I had HIV, not AIDS. They’re related, but they’re not the same thing—not that the facts mattered to the kids at Clarkstown Middle School.

Just like it didn’t matter that I wasn’t contagious, that HIV wasn’t like a cold or flu, that I posed no risk to them whatsoever.

Nor did it matter that there was nothing visible about my virus, that I looked and walked and talked exactly and completely like everyone else. It didn’t even matter that the kids who were giving me the hardest time had been my friends, my good friends, just last year.

You know how it is: I had something that others didn’t have. I was different.

And I was learning that when you live in a suburban neighborhood on the northwest side of Indianapolis, and you are in seventh grade, and all you want is to be surrounded by friends, different is about the very worst thing you can be.

What Was

Today, when I tell people that I took medicine every single day for almost a decade without ever once wondering why, they sometimes look at me like I have three heads. Or maybe like I’m the world’s biggest idiot.

I can see their point.

But from my earliest memories, the medicine has just been a part of my life.

There I am as a very young child, scrambling up onto the kitchen counter, folding my legs crisscross-applesauce, and waiting patiently. And there is my mother, twisting the child safety lid off a white plastic jar, scooping a heap of powder, and stirring it, still lumpy, into a plastic sippy cup filled with milk.

She places the lid on the cup and hands it to me. I make a face and begin to drink. The taste is awful; I call this drink “my yucky.” Still, I’m a dutiful child: I drink it all. I would have, every time, even if my mother hadn’t been watching me closely, her eyes focused on this ritual as if my life depended on it.

It did, of course, although I didn’t know that yet.

Other times, people ask about my hospital visits. There had to have been so many. Did I really think that was normal? The short answer is, yes. I did. Not only that, I liked it.

The Riley Hospital for Children is located in downtown Indianapolis. Its vast modern architecture and the hustle and bustle of the city around it seemed such an exciting contrast to our cozy one-story ranch home with its tidy patch of cut grass. Inside the hospital entrance, I looked up. All around the atrium I would see enormous teddy bears perched on beams high overhead, their legs dangling. I’d pass a shiny carousel

horse surrounded by pennies; each time, my mother and I both made wishes and tossed our own coins toward the animal. I’d wish for dolls and dresses, for trips to the water park, for cupcakes and Christmas. My mother made her wish silently.

When I asked what she wished for, she never told me. Instead, she would simply answer, “Same as last time, pumpkin.” She’d hug me close, then, and finish, “... Same as every time.”

We’d step into the glass elevators, real glass elevators, just like Willy Wonka’s, and rise to the third floor.

Waiting in the doctor’s office, I could never keep myself from touching the medical equipment. I squeezed the rubber blood pressure pump, slipped the plastic caps on and off of the otoscope, pulled down on the rubbery black coils that connected these tools to the wall.

“Stop messing with the doctor’s stuff,” my mom would always try to scold me, unable to completely hide the hint of a smile on her face. “She’s going to get mad at you, Paige!” But when Dr. Cox at last breezed into the room, in her funky shoes and chunky jewelry, she was never angry. Instead, she greeted me cheerfully.

“Paige! It’s good to see you!” Her flowing, loose-fitting clothes peeked out from beneath her lab coat. Her stethoscope hung confidently around her neck.

I loved seeing her. One day, I planned to be her.

“I’m going to have your job when I grow up,” I would announce proudly at my visits.

“I know you will.” Dr. Cox would smile back, brushing a streak of blond hair from her eyes and holding out a tongue depressor. She always took me seriously, not the way some grown-ups treat kids.

She would press the wooden depressor on my tongue. “Now say ahh.”

I told Dr. Cox everything. About school, and sleepovers with my friends, that I swam like a mermaid, which I knew because my mother said it was true. I told her I loved karaoke and that I could jump high as the birds on my trampoline. She listened and laughed, complimented my sparkly nails. She asked about my vacations, teachers, classmates....

I may have been her patient, just a young child, but Dr. Cox treated me like a real person, someone she genuinely liked. She wasn’t the only one. The nurses in the emergency room knew me by name, remembered details about both my health history and my life outside the hospital. They asked me about books I was reading, they cheered when I told them I’d learned to ride a bike. The lab technicians knew me, too—they asked me about school as they pricked my skin, distracting me by allowing me to hold the tubes that were filling up with my blood.

Being at a hospital so regularly, so young, sounds awful to folks who have no experience inside a place like Riley. But the truth is, I can think of far worse fates than to have a group of people this warm, this kind, be a part of your life from the start.

And when these things—the medicine, the hospital visits—become part of your routine before you even form your first memory—before you write your name for the first time, before you can skip, or turn a somersault, or even brush your teeth without assistance, the whole thing becomes a bit like the sun rising. If it somehow didn’t happen—if one morning the darkness never gave way to light, if the stars remained overhead even as the morning school bus lurched up to the corner and opened its doors for its line of bewildered kids—now that would get your attention. But as long as it happens, day after day without ever taking a break, you start to take the whole thing for granted. Your mind wanders to other things, like finishing your homework or an upcoming vocabulary test or last weekend’s sleepover.

Take it from me: the things that keep you alive can be like the hum of the refrigerator, or the television that your mom leaves on all day because she gets nervous when there’s too much quiet.

They’re just there, just a part of your world, barely even worth a mention.

Perhaps you think it would have been different for you—that you would wonder sooner, that you would clue in earlier that something is different here. You would have started asking questions, all those what/why/hows.

I’ll be honest: I’m not so sure about that.

And maybe that was my problem from the start—the fact that those thousands of doses of medicine had been so routine, so humdrum. Bitter-tasting, sure. A bummer, I guess. But still just a backdrop to the parts of my life that felt like they really mattered. Perhaps that was the reason everything that happened later was such a surprise to me. Maybe, in the end, it was the very regularity of it that left me so unprepared when it all went so badly.

And that’s how it was, year after year. My friend Azra went to her grandmother’s to swim in her pool. My friend Jasmine went to her brother’s baseball games. I went to see Dr. Cox. I took medicine and played soccer and dressed my Barbies and sang country songs with my mother and watched my crimson blood f low into clear plastic tubes.

It was just what I did. Nothing more.

I had plenty of friends, and it was, to be honest, a pretty good life.

Positive: A Memoir

- Genres: Nonfiction, Young Adult 14+

- hardcover: 288 pages

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- ISBN-10: 0062342517

- ISBN-13: 9780062342515