Excerpt

Excerpt

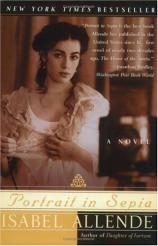

Portrait in Sepia

Chapter One

I came into the world one Tuesday in the autumn of 1880, in San

Francisco, in the home of my maternal grandparents. While inside

that labyrinthine wood house my mother panted and pushed, her

valiant heart and desperate bones laboring to open a way out to me,

the savage life of the Chinese quarter was seething outside, with

its unforgettable aroma of exotic food, its deafening torrent of

shouted dialects, its inexhaustible swarms of human bees hurrying

back and forth. I was born in the early morning, but in Chinatown

the clocks obey no rules, and at that hour the market, the cart

traffic, the woeful barking of caged dogs awaiting the butcher's

cleaver, were beginning to heat up. I have come to know the details

of my birth rather late in life, but it would have been worse not

to discover them at all, they could have been lost forever in the

cracks and crannies of oblivion. There are so many secrets in my

family that I may never have time to unveil them all: truth is

short-lived, watered down by torrents of rain. My maternal

grandparents welcomed me with emotion -- even though according to

several witnesses I was ugly as sin -- and placed me at my mother's

breast, where I lay cuddled for a few minutes, the only ones I was

to have with her. Afterward my uncle Lucky blew his breath in my

face to pass his good luck on to me. His intention was generous and

the method infallible, because at least for these first thirty

years of my life, things have gone well. But careful! I don't want

to get ahead of myself. This is a long story, and it begins before

my birth; it requires patience in the telling and even more in the

listening. If I lose the thread along the way, don't despair,

because you can count on picking it up a few pages further on.

Since we have to begin at some date, let's make it 1862, and let's

say, to choose something at random, that the story begins with a

piece of furniture of unlikely proportions.

Paulina del Valle's bed was ordered from Florence the year

following the coronation of Victor Emmanuel, when in the new

kingdom of Italy the echoes of Garibaldi's cannon shots were still

reverberating. It crossed the ocean, dismantled, in a Genoese

vessel, was unloaded in New York in the midst of a bloody strike,

and was transferred to one of the steamships of the shipping line

of my paternal grandparents, the Rodriguez de Santa Cruzes,

Chileans residing in the United States. It was the task of Captain

John Sommers to receive the crates marked in Italian with a single

word: naiads. That robust English seaman, of whom all that

remains is a faded portrait and a leather trunk badly scuffed from

infinite sea journeys and filled with strange manuscripts, was my

great-grandfather, as I found out recently when my past finally

began to come clear after many years of mystery. I never met

Captain John Sommers, the father of Eliza Sommers, my maternal

grandmother, but from him I inherited a certain bent for wandering.

To that man of the sea, pure horizon and salt, fell the task of

transporting the Florentine bed in the hold of his ship to the

other side of the American continent. He had to make his way

through the Yankee blockade and Confederate attacks, sail to the

southern limits of the Atlantic, pass through the treacherous

waters of the Strait of Magellan, sail into the Pacific Ocean, and

then, after putting in briefly at several South American ports,

point the bow of his ship toward northern California, that

venerable land of gold. He had precise orders to open the crates on

the pier in San Francisco, supervise the ship's carpenter while he

assembled the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle, taking care not to nick

the carvings, install the mattress and ruby-colored canopy, set the

whole construction on a cart, and dispatch it at a leisurely pace

to the heart of the city. The coachman was to make two complete

turns around Union Square, and another two -- while jingling a

little bell -- before the balcony of my grandfather's concubine,

before depositing it at its final destination, the home of Paulina

del Valle. This fanfaronade was to be performed in the midst of the

Civil War, when Yankee and Confederate armies were massacring each

other in the South and no one was in any mood for jokes or little

bells. John Sommers fulfilled the instructions cursing, because

during months of sailing that bed had come to symbolize what he

most detested about his job: the whims of his employer, Paulina del

Valle. When he saw the bed displayed on the cart, he sighed and

decided that that would be the last thing he would ever do for her.

He had spent twelve years following her orders and had reached the

limits of his patience. That bed still exists, intact. It is a

weighty dinosaur of polychrome wood; the headboard is presided over

by the god Neptune surrounded by foaming waves and undersea

creatures in bas-relief, and the foot, frolicking dolphins and

cavorting sirens. Within a few hours, half of San Francisco had the

opportunity to appreciate that Olympian bed. My grandfather's

amour, however, the one to whom the spectacle was dedicated, hid as

the cart went by, and then went by a second time with its little

bell.

"My triumph lasted about a minute," Paulina confessed to me many

years later, when I insisted on photographing the bed and knowing

all the details. "The joke backfired on me. I thought everyone

would make fun of Feliciano, but they turned it on me. I misjudged.

Who would have imagined such hypocrisy? In those days San Francisco

was a hornet's nest of corrupt politicians, bandits, and loose

women."...

Excerpted from PORTRAIT IN SEPIA © Copyright 2005 by

Isabel Allende. Reprinted with permission by Perennial, an imprint

of HarperCollins. All rights reserved.

Portrait in Sepia

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Harper Perennial

- ISBN-10: 0060936363

- ISBN-13: 9780060936365