Excerpt

Excerpt

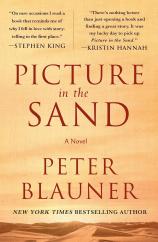

Picture in the Sand

1

As I start to write this story, you, my grandson, are thirteen years old and upstairs in your bedroom with the door closed, not speaking to your parents. I hear the distant percussion of booms and gunshots through the ceiling. You are playing one of your video games. I am in the den, watching an old movie and making a few random notes to myself.

The film is about a silent movie actress trying to be remembered in a world that has forgotten her. I’m afraid you would not like it or understand it. It’s in black-and-white, and it’s narrated by a dead man. But I wish you would come in and watch a few minutes. Because it would help me begin to explain myself. There is a scene coming up in which the actress goes to see the director who long before made her a star. His name is Cecil B. DeMille. I knew him in real life. He was one of the idols of my youth. And after all these years, it’s still hard for me to believe that I spent such a large part of my life behind bars for the crime of trying to destroy him.

But let me come back to that.

I was born in Egypt, between two wars and two worlds. I grew up just down the street from the pyramids, at the foot of the Giza Plateau. The Sphinx was only a short stroll from our front door. But the magnificent absurdity of my life, which led to all my misadventures and blessings, is that I preferred to go to the movies.

Our family lived in a mud brick house directly across the road from the Mena House Hotel, where all the celebrities of the day stayed. My mother was a chambermaid and my father was a golf caddy for the guests. He was a most excellent golfer himself. He liked to joke that he was the one who broke the Sphinx’s nose with a drive from the eighteenth hole.

I was a happy child, and why not? Every morning I would walk to school with my cousin and best friend, Sherif, past wandering chickens and quail in the road; tin roof shacks and smoldering village blacksmith forges; fragrant bakers’ ovens in the open air; and the souvenir shop where Sherif’s father sold Aladdin slippers, miniature mummies, and crocodile-head backscratchers to the tourists. Every afternoon I would come home to a house full of women: my mother and three older sisters talking gaily to nieces and cousins, conjuring splendid amalgams from room service leftovers, adding spaghetti marinara to traditional kushari, Carr’s water biscuits to mish and bissara, London broil to ful mudammas while songs like “Begin the Beguine” and “Moonlight Serenade” played on the radio.

I knew we were not rich, but my family treated me like a little prince of Egypt, because I was the only son. My mother brought home silk sheets from the guest rooms for me to sleep on and tailored clothes accidentally left in the hampers. My father let me ride in his golf cart and introduced me proudly to his favorite customers. In the spring, I competed in the pyramid races, somehow beating Sherif to the highest peak, even though he was as lean as a jackal and twice as fierce when he competed. My rewards were the shower of kisses and candies I received from my mother and sisters, and my first Yankee dollars from the tourists who cheered us on.

Sometimes I glimpsed famous guests like Mr. Churchill and Mr. Roosevelt on the hotel veranda. But I was aware of an older, more uncanny world on our side of the road. In those days, before the Aswan High Dam was built, the floodwaters of the Nile would come right up to the paws of the Sphinx. My classroom would be so drenched that I’d have to leap from desk to desk to keep my feet dry and avoid stepping on frogs.

Perhaps you think I exaggerate? Well, I come by it honestly. My neighbors passed down the old legends that had been around since the time of the pharaohs. Well into the middle of the twentieth century, they still believed that the course of daily life was afflicted by jinn and afreet and other invisible spirits in the air, that the evil eye could kill you, that raving unwashed madmen could cure rickets and bilharzia, and that the black cat around the village well transformed into an old crone at midnight who would curse your family if you tried to draw water after sundown. But again, none of those myths stirred me as much as what I saw when my mother started taking me to the movies.

I can still remember settling into the plush velvet seats and looking up at the red damask curtains of the Metro Cinema before the house lights slowly went down, ushering us into the mysteries of the darkness. This was long before TV was common in any Egyptian home, Alex. A celestial white beam shot through a tiny square in the wall behind us, as dragons of cigarette smoke from the orchestra section curled up toward the balcony where I sat with my mother, my two older sisters, and Sherif. That first film was Fantasia and, oh, I was overwhelmed, my grandson. It was like watching images from my own unconsciousness being projected onto that giant screen. The wild and florid colors, the cartoon mouse in the wizard’s robes, the marching broomsticks, the silhouette of the conductor, the “Rites of Spring” and the dinosaurs, the rising of the dead and the “Ave Maria.” I forgot the fact that my mother could only afford one small tub of popcorn for the five of us to share. I wanted to stay for the next showing, and the one after that, so we didn’t have to go back to our house, which had no toilet at the time and only intermittent electricity. But Sherif was tugging at her arm and my father was waiting for dinner, so she had to promise we would come back another time.

The next week was even better. We went to a theater called the Avalon. They were showing a British movie called The Thief of Bagdad. It was not a cartoon. It had real people in it, doing utterly impossible things. Flying through the air and coaxing genies from bottles. Even more amazing, one of those real people was a brown boy named Sabu, who was even darker than I was! And he wasn’t just a silent servant in a scene or two but one of the stars of the picture. When he rode the magic carpet at the end to save the sultan and the princess from the wicked vizier who’d imprisoned them, I was carried away with him, imagining I, Ali Hassan, could be the hero rising up from lowly origins to save the day.

After that, I made my mother take me back every week, so we could hold hands and dream together in the dark. Sometimes we would take my cousin and my sisters. Sometimes it would be just the two of us. We saw everything: Egyptian films, French ones, Italian, English, and Spanish. We saw comedies and musicals, romantic melodramas and gangster pictures. But my favorites were American movies. Especially the Westerns with heroic cowboys and black-hatted outlaws having blazing shoot-outs in deserts that vaguely resembled the one we lived in but somehow seemed to be on another planet. Just the names bring me back to those exquisite days of my childhood. Stagecoach, They Died with Their Boots On, The Plainsman. The directors’ names would appear big as the columns of the Luxor temples before the action, monuments to be worshipped. Mr. John Ford, Mr. Raoul Walsh, and the most monumental name of them all, Mr. Cecil B. DeMille.

I began to think of how I might rise above my circumstances like Sabu on his magic carpet and eventually become one of them.

But then the houselights would come on and real life would interrupt my dreams.

My village, my city, my country had been spared the worst effects of the war, until after the battles of El Alamein. Then there was an outbreak of typhus. My aunt Amina, Sherif’s mother, fell ill with the fever first. She sweated and could not get out of bed. She complained of horrible pains in her abdomen. Then she shook and closed her eyes, and never opened them again. His father, Hamid, the shop owner, died a few hours after her. The very next day, my sisters, Mariam and Rana, fell into a swoon and passed within hours of each other. Then my dear stalwart mother, who’d been running around trying to take care of them all, and of our neighbors as well, got a raging fever. She curled up and cried out like she was being stabbed by a hundred invisible knives. I stood by helpless, clutching a damp washcloth. The hotel doctor could not help her, nor could the village medicine man. I went with my father to the Al-Hussein Mosque and prayed as hard as I could, promising Allah I would give anything if he would spare her.

She died anyway.

My world went from color to black-and-white. More than a dozen in our village died. My father and other men retreated into drinking and mournful silences at home. I became withdrawn as well, barely able to pay attention in school. It was Sherif who saved me. My cousin, only six months older, had always been more like a big brother to me. He insisted the problem was not that God had failed us but that we had failed him, by not being devout enough. He started dragging me to our local mosque every day, showing me where to find solace and explanation in the Holy Koran and the hadith. Faith lightened my burden in those places, especially when I saw older men who’d suffered in the plague, praying alongside me.

But that was not enough for Sherif. He always had a talent for pushing things. He declared he was forming a junior promotion of virtue society in our village and appointed me as his vice president. We would spend hours designing handbills with sayings of the Prophet Muhammad and then running around like a couple of mischief-makers slipping papers of hadith under the doors of hotel guests and lecturing our neighbors about the sins of drinking and lasciviousness. To tell you the truth, I rather liked it, because most people received us with tolerant good humor, giving us tea and not reminding Sherif that his father had run a side business selling pornography in the back room of his shop. But then one day, a widow with five children turned on us and started yelling that my mother was to blame for bringing the plague to our village because she supposedly consorted with foreigners as a maid and took us to the movies instead of religious school.

I was hurt and deeply offended, of course. But Sherif actually attacked the widow physically—to the point that I had to hold him back. After that, he became more remote and turned inward. He claimed he was taking private lessons from a local imam, but I suspect that he was just smoking a lot of hashish. He began talking a lot about the need to “do something” to change our country and put us “back on the path toward the one true God”—though I pointed out that our country used to believe in many gods. I was secretly relieved when he went off to join a teenage volunteer brigade fighting alongside the Egyptian Army against the common enemy of the Arab world—the newly declared State of Israel. I paid little attention to the fact that the brigade was organized by the Ikhwan, a religious group that was also known as the Muslim Brotherhood. Many people in our country belonged to that movement and shared its objectives. I thought if they could find some use for Sherif’s restless urges, it was all to the good.

In his absence, I started working as a busboy at the hotel, using my meager wages to help my father pay bills and occasionally take refuge at the Metro or the Avalon movie theater where I’d spent so many Saturday matinees. Except now that I was older, the cinema became not just my sanctuary but my classroom. I learned about love and courage and success. And it was where I found my own path forward. After seeing Mr. David Lean’s adaptation of Great Expectations, I was inspired to put pen to paper to write a review. On a whim, I sent it to Professor Ibrahim Farid, one of the great literary critics of Egypt, whose name I had seen in culture stories in the newspapers. For reasons known only to God, he read it and became convinced that I had insight and promise. He persuaded the admissions office to accept my application into the King Fuad I University in Cairo.

Copyright © 2023 by Peter Blauner