Excerpt

Excerpt

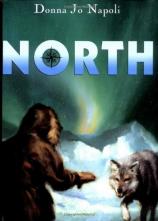

North

Chapter One

Alvin stood at the window and looked through the bars. The sidewalk outside was still empty. If he hurried, he could get to school before everyone else. He wouldn't have to talk to anyone about Christmas.

The steam kettle screeched. Alvin ran into the kitchen and turned it off. He could do without hot chocolate. It was more important to avoid the other kids. And Grandma would use the hot water to make tea anyway, so he hadn't wasted the gas. He grabbed his new backpack with one hand and his jacket with the other and ran for the door.

"Get that coat on, Alvin," his mother called from her bedroom. There was no way she could see him.

"How does she always know?" he muttered.

"The mamma knows," said Grandma. She was sitting on the couch in the dark. "Grandma, what you doing there?"

"Taking a rest. Get your jacket on or your mamma won't be happy."

A rest in the morning? How long had Grandma been up? "I don't care," he said, even as he pulled the jacket on.

"Yes, you do, boy. If the mamma ain't happy, ain't nobody happy." Grandma laughed. She loved that saying: If the mamma ain't happy, ain't nobody happy. She gave Mamma a sweatshirt with that saying on it for the fourth day of Kwanzaa. Mamma didn't love it as much as Grandma did, especially since she hated words like ain't. But she wore it to sleep in, because Grandma had bought it at a store on Mount Pleasant Street that sold only goods made by African-American–owned businesses. So the sweatshirt was a symbol of a Kwanzaa principle -- as Grandma put it, "You buy from me and I'll buy from you." Mamma believed Kwanzaa was one of the good things that had happened to black people in her lifetime. Grandma didn't care one way or the other about Kwanzaa, but she was ready to take advantage of anything that would allow her a belly laugh.

Alvin zipped up his jacket, kissed Grandma quick on the cheek, and left.

It was only a few blocks to Bancroft Elementary. The morning was pretty cold, but not what it should have been for January in Washington, D.C. The gibbons at the zoo, just six blocks away, screamed good morning to one another in high voices that echoed all over Mount Pleasant. He loved the zoo. Someday he'd go to the Asian jungles where the gibbons lived free. And he'd go to the Amazon, and Africa, too.

Yeah, especially Africa. He'd go to Africa first, because the last book he'd read on primates said the gorillas were threatened with extinction. No more gorillas. Intelligent, gentle beasts, gone.

Alvin pulled up the collar of his jacket and jammed his hands into his pockets. He walked with his eyes glued to the sidewalk.

The dog behind the wood fence on Park Road barked wildly. Alvin ran half a block before his heart slowed again. He knew the fence was tall, but it never reassured him enough. He was afraid of dogs. None of his friends owned one.

"That you, Alvin?" called Shastri.

Alvin kept walking without looking around.

"Hey, Dwarf, that you?"

Shastri's footsteps got louder. Alvin stopped and waited.

"What's the rush?" Shastri came up beside him.

Alvin had to make three steps for every two of Shastri's. He looked up at his best friend, the friend he'd been avoiding since Christmas Day. "Hi."

"We'll get there early, going at this hour. I couldn't believe that was you I saw from the window. I had to stuff my toast in my mouth."

"Sorry," Alvin muttered.

"'S Okay. You're not going to believe this. I got it. I got the mountain bike."

Alvin knew Shastri would have gotten it. He tried to smile.

"It's perfect. Cold blue. It can go anywhere. You got to come see it."

"Yeah," said Alvin. They were at the school doors now. Luckily, Alvin and Shastri weren't in the same classes this year; at least he wouldn't have to listen to this all day long. "I got to go," said Alvin, "I got something to do."

"Cool." Shastri gave a quick nod. "After school?"

Alvin waved and went to his classroom, willing himself not to let jealousy get the better of him.

The thing was, Alvin needed a mountain bike, actually needed it. Uncle Pete had promised to take him on a bike trip over spring break if Mamma bought it. A trip through Maryland, past farms, through woods. Camping the whole way. Like pioneers.

Uncle Pete used to take Alvin camping when he lived here. But he'd gotten a job in Philadelphia two years ago and moved away. He came back for a weekend a few times a year. And Alvin had visited him in June. Mamma had ridden up on the train with him, and Uncle Pete had ridden back with him. The whole way they'd talked about plans for the bike trip.

When Alvin told Shastri he was dreaming about a mountain bike, Shastri started dreaming, too. Alvin didn't say anything more about it -- the bike and the trip became Alvin's private hope, sacred almost. But Shastri started wanting that bike so much that he could hardly talk about anything else. And look what happened -- Shastri got the bike and Alvin didn't.

And Shastri didn't even need his. His parents took him to all kinds of new places.

A bike. With a bike, Alvin wouldn't have needed anyone to take him anywhere. He could have gone on his own.

Excerpted from NORTH © Copyright 2004 by Donna Jo Napoli. Reprinted with permission by Greenwillow Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

North

- hardcover: 352 pages

- Publisher: HarperCollins

- ISBN-10: 0060579870

- ISBN-13: 9780060579876