Excerpt

Excerpt

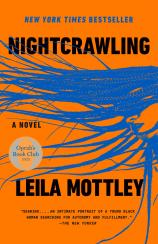

Nightcrawling

The swimming pool is filled with dog shit and Dee’s laughter mocks us at dawn. I’ve been telling her all week that she’s looking like the crackhead she is, laughing at the same joke like it’s gonna change. Dee didn’t seem to mind that her boyfriend left her, didn’t even seem to care when he showed up poolside after making his rounds to every dumpster in the neighborhood last Tuesday, finding feces wrapped up in plastic bags. We heard the splashes at three a.m., followed by his shouts about Dee’s unfaithful ass. But mostly we heard Dee’s cackles, reminding us how hard it is to sleep when you can’t distinguish your own footsteps from your neighbor’s.

None of us have ever set foot in the pool for as long as I’ve been here; maybe because Vernon, the landlord, has never once cleaned it, but mostly because nobody ever taught none of us how to delight in the water, how to swim without gasping for breath, how to love our hair when it is matted and chlorine-soaked. The idea of drowning doesn’t bother me, though, since we’re made of water anyway. It’s kind of like your body overflowing with itself. I think I’d rather go that way than in some haze on the floor of a crusty apartment, my heart out-pumping itself and then stopping.

This morning is different. The way Dee’s laugh swirls upward into a high-pitched sort of scream before it wanders into her bellow. When I open the door, she’s standing there, by the railing, like always. Except today she faces toward the apartment door and the pool keeps her backlit so I can’t see her face, can only see the way her cheekbones bob like apples in her hollow skin. I close the door before she sees me.

Some mornings I peek my head into Dee’s unlocked door just to make sure she’s still breathing, writhing in her sleep. In some ways I don’t mind her neurotic laughing fits because they tell me she’s alive, her lungs haven’t quit on her yet. If Dee’s still laughing, not everything has gone to shit.

The knock on our apartment is two fists, four pounds, and I should have known it was coming, but it still makes me jump back from the door. It ain’t that I didn’t see Vernon making his rounds or the flyer flipping up and drifting back into place on Dee’s door as she stared at it, still cackling. I turn and look at my brother, Marcus, on the couch snoring, his nose squirming up to meet his brows.

He sleeps like a newborn, always making faces, his head tilting so I can see his profile, where the tattoo remains taut and smooth. Marcus has a tattoo of my fingerprint just below his left ear and, when he smiles, I find myself drawn right to it, like another eye. Not that either of us has been smiling lately, but the image of it—the memory of the freshly rippling ink below his grin—keeps me coming back to him. Keeps me hoping. Marcus’s arms are lined in tattoos, but my fingerprint is the only one on his neck. He told me it was the most painful one he’d ever gotten.

He got the tattoo when I turned seventeen and it was the first day I ever thought he might just love me more than anything, more than his own skin. But now, three months from my eighteenth birthday, when I look at my quivering fingerprint on the edge of his jaw, I feel naked, known. If Marcus ended up bloodied in the street, it wouldn’t take much to identify him by the traces of me on his body.

I reach for the doorknob, mumbling, “I got it,” as if Marcus was ever actually gonna put feet to floor this early. On the other side of the wall, Dee’s laughter seeps into my gums like salt water, absorbed right into the fleshy part of my mouth. I shake my head and turn back to the door, to my own slip of paper taped to the orange paint. You don’t have to read one of these papers to know what they say. Everyone been getting them, tossing them into the road as if they can nah, nigga themselves out of the harshness of it. The font is unrelenting, numbers frozen on the flyer, lingering in the scent of industrial printer ink, where it was inevitably pulled from a pile of papers just as toxic and slanted as this one and placed on the door of the studio apartment that’s been in my family for decades. We all known Vernon was a sellout, wasn’t gonna keep this place any longer than he had to when the pockets are roaming around Oakland, looking for the next lot of us to scrape out from the city’s insides.

The number itself wouldn’t seem so daunting if Dee wasn’t cracking herself up over it, curling into a whole fit, cementing each zero into the pit of my belly. I whip my head toward her, shout out over the wind and the morning trucks, “Quit laughing or go back inside, Dee. Shit.” She turns her head an inch or two to stare at me and smiles wide, opens her mouth until it’s a complete oval, and continues her cackle. I rip the rent increase notice from the door and return to our apartment, where Marcus is serene and snoring on the couch.

He’s lying there sleeping while this whole apartment collapses around me. We’re barely getting by as is, a couple months behind in rent, and Marcus has no money coming in. I’m begging for shifts at the liquor store and counting the number of crackers left in the cupboard. We don’t even own wallets, and looking at him, at the haze of his face, I know we won’t make it out of this one like we did the last time our world fractured, with an empty photo frame where Mama used to be.

I shake my head at his figure, long and taking over the room, then place the rent increase notice in the center of his chest so it breathes with him. Up and down.

I don’t hear Dee no more, so I pull on my jacket and slip outside, leaving Marcus to eventually wake to a crumpled paper and more worries than he’ll try to handle. I walk along the railing lined in apartments and open Dee’s door. She’s there, somehow asleep and twitching on the mattress when just a few minutes ago she was roaring. Her son, Trevor, sits on a stool in the small kitchen eating off-brand Cheerios out of their box. He’s ten and I’ve known him since he was born, watched him shoot up into the lanky boy he is now. He’s munching on the cereal and waiting for his mother to wake up, even though it’ll probably be hours before her eyes open and see him as more than a blur.

I step inside, quietly walking up to him, grabbing his backpack from the floor and handing it to him. He smiles at me, the gaps in his teeth filled in with soggy Cheerio bits.

“Boy, you gotta be getting to school. Don’t worry ’bout your mama, c’mon, I’ll take you.”

Trevor and I emerge from the apartment, his hand in mine. His palms feel like butter, smooth and ready to melt in the heat of my hand. We walk together toward the metal stairwell, painted lime green and chipped, all the way down to the ground floor, past the shit pool, and through the metal gate that spits us right out onto High Street.

High Street is an illusion of cigarette butts and liquor stores, a winding trail to and from drugstores and adult playgrounds masquerading as street corners. It has a childlike kind of flair, like the perfect landscape for a scavenger hunt. Nobody ever knows when the hoods switch over, all the way up to the bridge, but I’ve never been up there so I can’t tell you if it makes you want to skip like it does on our side. It is everything and nothing you’d expect with its funeral homes and gas stations, the street sprinkled in houses with yellow shining out the windows.

“Mama say Ricky don’t come around no more, so I got the cereal all to myself.”

Trevor lets go of my hand, slippery, sauntering ahead, his steps buoyant. Watching him, I don’t think anybody but Trevor and me understand what it’s like to feel ourselves moving, like really notice it. Sometimes I think this little kid might just save me from the swallow of our gray sky, but then I remember that Marcus used to be that small, too, and we’re all outgrowing ourselves.

We take a left coming out of the Regal-Hi Apartments and keep walking. I follow Trevor, crossing behind him as he ignores the light and the rush of cars because he knows anyone would stop for him, for those glossy eyes and that sprint. His bus stop is on the side of the street we just crossed from, but he likes to walk on the side where our park is, the one where teenagers shoot hoops without nets every morning, colliding with each other on the court and falling into fits of coughs. Trevor slows, his eyes fixated on this morning’s game. It looks like girls on boys and nobody is winning.

I grab Trevor’s hand, pulling him forward. “You not gonna catch the bus if you don’t move those feet.”

Trevor drags, his head twisting to follow the ball spin up, down, squeaking between hands and hoops.

“Think they’d let me play?” Trevor’s face wobbles as he sucks on the insides of his cheeks in awe.

“Not today. See, they don’t got a bus to catch and your mama sure won’t want you out here getting all cold missing school like that.”

January in Oakland is a funny kind of cold. It’s got a chill, but it really ain’t no different from any other month, clouds covering all the blue, not cold enough to warrant a heavy jacket, but too cold to show much skin. Trevor’s arms are bare, so I shrug off my jacket, wrapping it around his shoulders. I grab his other hand and we continue to walk, beside each other now.

We hear the bus before we see it, coming around the corner, and I whip my head quick, see the number, the bulk of this big green thing rumbling toward us.

“Let’s cross, come on, move those feet.”

Ignoring the open road and the cars, we run across the street, the bus hurtling toward us and then pulling over to the bus stop. I nudge Trevor forward, into the line shuffling off the curb and into the mouth of the bus.

“You go on and read a book today, huh?” I call out to him as he climbs on.

He looks back at me, his small hand raising up just enough that it could be called a wave goodbye or a salute or a boy getting ready to wipe his nose. I watch him disappear, watch the bus tilt back up onto its feet, groan, and pull away.

A couple minutes later, my own bus creaks to a stop in front of me. A man standing near me wears sunglasses he doesn’t need in this gloom, and I let him climb on first, then join, looking around and finding no seats because this is a Thursday morning and we all got places to be. I squeeze between bodies and find a pocket of space toward the back, standing and holding on to the metal pole as I wait for the vehicle to thrust me forward.

In the ten minutes it takes to get to the other side of East Oakland, I slip into the lull of the bus, the way it rocks me back and forth like I imagine a mother rocks a child when she is still patient enough to not start shaking. I wonder how many of these other people, their hair shoved into hats, with lines moving in all directions tracing their faces like a train station map, woke up this morning to a lurching world and a slip of paper that shouldn’t mean more than a tree got cut down somewhere too far to give a shit about. I almost miss the moment to pull the wire and push open the doors to fresh Oakland air and the faint scent of oil and machinery from the construction site across the street from La Casa Taquería.

I get off the bus and approach the building, the blackout windows obscuring the inside from sight and its blue awning familiar. I grab the handle to the restaurant door, open it, and immediately smell something thundering and loud in the darkness of the shop. The chairs are turned over on the tables, but the place is alive.

“You don’t turn the lights on for me no more?” I call out, knowing Alé is only a few feet away but she feels farther in the dark. She steps out from a doorway, her shadow groping for the light switch, and we are illuminated.

Alejandra’s hair is silky and black, spilling from the bun on top of her head. Her skin is oily, slick with the sweat of the kitchen she has spent the past twenty minutes in. Her white T-shirt competes with Marcus’s shirts for most oversized and inconspicuous, making her look boyish and cool in a way that I never could. Her tattoos peek out from all parts of her and sometimes I think she is art, but then she starts to move and I remember how bulky and awkward she is, her feet stepping big.

“You know I could kick you outta here real quick.” Alé strides closer, looks like she’s about to perform the black man’s handshake, until she realizes I am not my brother and instead opens her arms. I am mesmerized by her, the way she fills up space in the room like she fills up that drooping shirt. Here, I settle into the most familiar place that I have ever lived, her chest against my ear, warm and thumping.

“You best have some food in there,” I tell her, pulling away and turning to strut into the kitchen. I like to swing my hips when I walk around Alé, makes her call me her chava.

Alé watches me move and her eyes dart. She starts to run toward the kitchen door just as I rush there, racing, pushing each other to squeeze inside the doorway, laughing until we cry, spreading out on the floor as we step on each other’s limbs and don’t care about the bruises that’ll paint us blue tomorrow. Alé beats me and stands at the stove scooping food into bowls while I’m on my knees heaving. She chuckles slyly as I get up and then hands me a bowl and spoon.

“Huevos rancheros,” she says, sweat drip-dripping down her nose.

It is hot and fuming, deep red with eggs on top.

Nightcrawling

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 288 pages

- Publisher: Vintage

- ISBN-10: 0593312600

- ISBN-13: 9780593312605