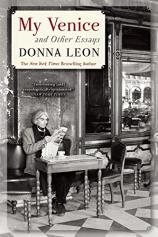

My Venice and Other Essays

Review

My Venice and Other Essays

I haven’t read a volume of essays in quite some time, and with this one, I am reminded that they are less about the virtues or deficits of any particular piece and more about whether you want to spend time in the author’s company. Donna Leon, I’m delighted to say, is literate, witty and contentious, with a ready sense of humor and an eye for the absurd. I’d love to have a cappuccino with her.

When I say “have a cappuccino,” I mean it literally, as I read the book while staying in Venice and am still there as I write. This happy coincidence makes it possible to test Leon’s observations on the spot, as it were. In the title essay, “My Venice” --- the best in the book --- she has some splendid insights about the implications of the absence of motorized vehicles in this city. The need to walk so much (the only “buses” and “taxis” are waterborne, no door-to-door anything) automatically puts you into direct contact with your neighbors, encouraging a sense of community as well as a taste for gossip (with only 60,000 residents when Leon wrote this --- it’s closer to 40,000 now, a restaurant owner told me last week --- La Serenissima really is a provincial town). It also “forces upon us a daily confrontation with the limits of our physical being,” Leon writes. “If we want to have it, we have to be able to carry it home or find someone willing to do that for us. Because of this, age is harder to ignore or deny….” Venice, in other words, offers a healthy counterweight to the modern tendency to pursue eternal youth and cleave to the impersonal individualism of car or Internet.

"Donna Leon, I’m delighted to say, is literate, witty and contentious, with a ready sense of humor and an eye for the absurd. I’d love to have a cappuccino with her."

Although this 30-year resident loves Italy’s “disorderly, humane beauty,” she does not romanticize Venetians. Yet she doesn’t stereotype them, either. Both their foibles and their allure are subtly and deftly described in essays about bureaucracy, neighbors, immigrants, food, trash, organized panhandling, and irresponsible dog owners (the last two regularly bedevil my life and besmirch the streets). Most of these essays are agreeably pithy, as Leon knows how to move seamlessly and swiftly from a specific incident to a larger, deeper point.

When MY VENICE leaves Venice proper, it becomes a bit more uneven (one reason I haven’t read an essay collection in a while is that they often consist of a few outstanding pieces surrounded by lesser efforts). Her second section, “Music,” is a case in point. Leon is an aficionado of baroque opera, and I share that arcane passion (and I cheer, too, her rage at talkers in theaters), but I think these fairly specialized essays would hold little appeal for a reader who is not already hooked on Handel (the longish profile of Anne Sofie von Otter seems to have emigrated from some other book).

Leon’s essays about animals (“On Mankind and Animals”) are better --- charming, really --- as they lay bare the tension between her affection for Gladys, the endearing chicken, or Gastone, the raffish cat; and the killing rage that overtakes her when other creatures (mice, dormice, moles, and the like) threaten to destroy her summer house in the mountains (every Venetian of means seems to have one, I guess to escape the tourists and the heat). I would say only that too many of the essays in this section strike the same “they’re ruining my 16th-century beams” note.

In “On Men,” Leon is most effective when she is most particular. “The Italian Man,” for example, is a sharp yet sympathetic look at the species; the horrifying “Saudi Arabia,” a condemnation of the misogynistic nation where she spent nine ghastly months teaching. I was less thrilled with her attacks on such legitimate but predictable targets as foot-binding, rationalizations for rape and other forms of sexual abuse, eroticized album covers, and “personals” ads. Although I share her feminist outrage, these essays have a slightly dated feel, perhaps because she wrote them some time ago (computer matchmaking, for example, having replaced “personals”).

Similarly, in Leon’s “On America” section, her critiques of CNN reporters as “pornographers of pain” or of American obesity and prudishness seem to me to lack freshness. Far more engaging (under the heading of “Books”) is a short, sardonic report on a lunch with Barbara Vine (aka Ruth Rendell, one of my favorite mystery writers and apparently Leon’s friend and cohort) and the terrific “Suggestions on Writing the Crime Novel,” which expresses some of her frustrations as a teacher and hints at her own creative process.

One more thing: I said at the beginning of this review that I would love to have a coffee with Leon (and it’s true, I would), but I think I’d find her friendly yet remote. Her voice in MY VENICE, while dagger-smart and often flat-out funny, is not really personal, certainly not confessional (no self-indulgent outpourings here). Although she includes three brief, poignant pieces about her family, they don’t reveal much.

Leon, in other words, remains an enigma --- which, for a writer of mysteries, could be a very good thing.

Reviewed by Kathy Weissman on January 8, 2014

My Venice and Other Essays

- Publication Date: November 11, 2014

- Genres: Essays, Nonfiction

- Paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Grove Press

- ISBN-10: 0802122809

- ISBN-13: 9780802122803