Excerpt

Excerpt

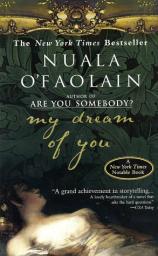

My Dream of You

Chapter 1

By the time I was middle-aged I was well defended against crisis, if it came from outside. I had kept my life even and dry for a long time. I'd been the tenant of a dim basement, half-buried at the back of the Euston Road, for more than twenty years. I didn't like London particularly, except for the TravelWrite office, but I didn't see much of it. Jimmy and I, who were the main writers for the travel section of the NewsWrite syndicate, were on the move all the time. We were never what you'd call explorers; we never went anywhere near war or hunger or even discomfort. And we wrote about every place we went to in a cheerful way: that was the house rule. But we had a good boss. Even if it was the fifth "Paris in Springtime" or the third "Sri Lanka: Isle of Spices," Alex wouldn't let us get away with tired writing. Sometimes Jimmy accused him of foolish perfectionism, because every TravelWrite piece was bought immediately anyway. But having to please Alex was good for us. And then, people do read travel material in a cheerful frame of mind, imagining themselves at leisure and the world at its best. It's an intrinsically optimistic thing, travel. Partly because of that, but mostly because Alex went on caring, I liked my work.

I even liked the basement, in a way, in the end. I don't suppose more than a handful of people ever visited it, in all the time I was there. Jimmy was my close friend and since he'd come to TravelWrite from America he'd lived twenty minutes away, in Soho, but we'd never been inside each other's places. It was understood that if one of us said they were going home, the other didn't ask any questions. Once, early on, he said he was going home, and I happened to see, from the top of the bus, that he had stopped a taxi and was in fact going in the opposite direction. After that, I deliberately didn't look around when we parted. Anyway, my silent rooms were never sweetened by the babble the two of us had perfected over the years. And for a long time, there hadn't been anyone there in the morning when I woke up. Sex was a hotel thing. I don't think I'd have liked to disturb the perfect nothingness of where I lived.

Then a time came when I began to lose control of the evenness and the dryness.

I was waiting for my bag in the arrivals hall at Harare airport when I fell into conversation with the businessman in the exquisite suit who was waiting beside me. Favorite airlines, we were chatting about.

Royal Thai executive class is first-rate, he said.

Ah, don't tell me you fall for all that I-am-your-dusky-handmaiden stuff, I laughed at him.

Those girls really know how to please, he went on earnestly, as if I hadn't spoken at all. And there was a porter with gnarled bare feet asleep on the baggage belt, and when it started with a jolt the poor old man fell off in front of us, and all the businessman did was step back in distaste and then take out a handkerchief and flick it across the glossy toe caps of his shoes as if they'd been polluted. But I accepted his offer of a lift into town, all the same. We were stopped for a moment at a traffic light beside a bar that was rocking with laughter and drumming.

They're very musical, the Africans, he said. Great sense of rhythm.

Just what are you doing, I asked myself, with Mr. Dull here?

I half-knew: no, quarter-knew. But if nothing more had happened I would never have given it a conscious thought.

Men can't allow themselves that vagueness. At his hotel he said, Would you like to come in for a drink? Or would you like to come up to the room while I freshen up? I've rather a good single malt in my bag.

I propped myself against the headrest of his big bed and sipped the Scotch and watched him deploy his neat things-his papers, his radio, his toiletries. When he came out of the bathroom with his shirt off and the top of his trousers open, I was perfectly ready to kiss and embrace. I was dead tired. I'd had a drink. I was completely alone in a foreign country. I was more than willing to hand myself over to someone else.

But very soon I was frowning behind his corpse-white back.

If only I knew how to take charge of this myself, I thought. If I could be the real thing myself, I could bring him with me. . . .

I honestly don't know how any person could make as little of the living body as that man did. Even the best I could do hardly made him exclaim. But he seemed to be delighted with the two of us, afterwards. At least I thought he was. He invited me to have dinner with him the next night, and I accepted, though I didn't much want to struggle through hours of trying to make conversation. I was in a great humor when he saw me into a taxi. It had been human contact, hadn't it? I was a generous woman, wasn't I, if I was nothing else? I hummed as I hung my clothes in the wardrobe of my mock-Tudor guesthouse, under huge jacaranda trees that in the streetlights looked as if their swathes of blossom were black. My favorite thing: a hotel bedroom in a new place.

The phone rang. It was Alex to say that he needed Zimbabwe wildlife copy within forty-eight hours.

I suppose you think that elephants and giraffes just walk around downtown Harare like people do in London? I shouted sarcastically down the phone. I suppose you think they have a game park in this guesthouse where I have just arrived. Then I hung up.

When the phone rang again I picked up, ready to do a deal about the deadline. But it was the businessman.

How are you, my little Irish kitten? he said. I am thinking of you.

Oh, really? I said, embarrassed. Kitten. I was forty-nine.

Unfortunately, he said, I must go out of town.

One hour after I'd been with him! He hadn't even waited till the next day.

And that's what I learned from him-that my heart was still ridiculously alive. I was sincerely hurt. What had I done wrong? I actually swallowed back tears.

And then, he continued, I must go directly back to my office.

There was nothing between the man and me-nothing, not even liking. But because of the memory of some wholeness, or the hope of some regeneration, I would have dropped whatever I'd planned, just to go back to scratching around on his bed.

I cannot go on like this, I said to myself. Tears!

I went on to the east a few days later to do a quick piece about a hot springs resort in the Philippines. I went straight to the famous waterfall, and though the humid, grayish air smelled like weeds rotting in mud and there were boys everywhere along the paths between the flowering trees, begging, or offering themselves as guides, it was possible to see that this was a marvelous spot, with hummingbirds sipping from the green pools that trembled under each fall before silently overflowing and sliding down the smooth rock to the next terrace. It was going to be easy to put a positive spin on the place. I made notes and took photos of the birds for identification, and then I got a bus to Manila. It arrived in the sweltering heat and dust of the evening rush. My hotel was on the far side of a busy dual carriageway. I started across the road, and reached the road divider where there was a bit of a dust-covered low hedge. A small hand came out of the hedge. I bent down. Two dirty-faced girls of seven or eight had a box under the hedge with an infant sleeping in it.

Dollar! the girl said. Then she stood on the road divider with the traffic going past on both sides and lifted the skirt of her ragged frock and pushed her delicate pelvis in threadbare panties forward. I didn't know what she meant, and maybe she didn't, either.

What money I had in my pockets I gave her, and then, instead of checking in to the hotel I got a taxi to the airport, looking neither left nor right.

There are children living in the middle of the road, I said.

Yes, the driver said. The country people come to town and they live in the street.

There was silence. He flicked on a Petula Clark tape.

After he took my money, outside departures, he said, We don't need no fuckin' grief from some old bitch.

The flight back to Europe was very long. I sat in the dark with my eyes open and grainy while the other passengers slept. The man beside me had slumped to one side, the napkin from the meal still tucked into his collar, like a baby's bib.

I was ashamed of myself at first for the egotistic way I reacted to the children in the middle of the road. They made me think about myself-me, me, me as usual-instead of the injustice of the world. But then I thought, Isn't it some kind of good, that a person can be shocked into truthfulness, even if it's only for a few hours and only with herself? I sat in the thick night air of the plane and I thought, If anyone had said to you, all these years, are you interested in sex? you'd have said, haughtily, No. I'm interested in passion. Passion. I murmured the word half out loud. What passion? It was never real excitement that got you into bed; it was hope, like some stubborn underground weed. Look at the way you've believed every time, at the first brush of a hand across a breast, that the roof over your life was sliding back and a dazzling, starry firmament was just coming into view. When it never happened. When a one-night stand has never, in all the years, done what you wanted it to do. What's more, the whole thing is getting more and more pathetic. The truth is, I said to myself, that the older you get, the more grateful you are for being wanted on any terms, by anybody.

But if I stopped all that, how would I ever meet anyone? If I didn't have this kind of sex life, I'd have none! Then I thought, But should it even be called sex? Look at the businessman in Harare. You're not even giving them any pleasure anymore, never mind getting any for yourself.

Then I started to smile, remembering Harare, at something else that had happened there. I'd got talking to a big, warm woman who was hanging out the guesthouse laundry while I was sitting on a back porch, working at my laptop. I helped her with the flapping sheets. Later I walked across town with her to see the room in a township that she'd raised her family in. We sat on the bed telling each other our life stories while she leaned across to the cooking ledge and made a stew. She took down a plastic carrier bag from a nail on the wall and showed me her treasures. Her radio that got two stations. Her conical pink bra, for best occasions. I went with her when she poured the stew into a bucket to sell around the big, bare beer halls. She made a wonderful sexy comedy out of offering it, and after a while I stopped being shy and joined in the spree. The men laughed their heads off at the sight of us two women and scooped the stew into tin bowls beside their bottles of beer. We danced around and shrugged and rubbed ourselves in a parody of excitement, and wiggled our bosoms at the fellas. By the time the whole pot of stew was sold we had a band of children following us and we were weak with laughter.

I do still know how to live, I said to myself.

On the plane the man who was asleep in the seat beside me had let his head somehow fall onto his plump fists-a wide band on one finger gleaming in the dark-and he was making grumbling noises in his sleep at the discomfort. I eased him into a better position as carefully as I could. In the end, I slept, too.

In London I tried to raise Jimmy on his mobile. We'll have to face up someday to all the awful things in the world, I wanted to say to him. If he'd allow me. He hated me getting serious.

Jimmy sure wants things kept cool, I once said to Roxy, the office secretary.Well, you're a bit too emotional by any standards, she said to me.

Roxy was so exceptionally stolid that I didn't have to take this remark very seriously. But I had squirreled it away to examine it. No one in my life told me anything about myself except Roxy and Jimmy and, occasionally, usually crossly, Alex. In that way the three people I worked with were my family.

Jimmy wasn't answering his mobile. It occurred to me that he was in New York. I sent him an e-mail.

I need to talk to you, Jimmy, it said. I think I've had it with TravelWrite. I'm getting old, sweetheart. The good has gone out of the job.

I sent another one half a minute later.

Not just out of the job, Jimmy-the good has gone out of me.

Jimmy had been at the Mercer but he'd checked out. When I finally got to talk to him he said the place was so fashionably young that it made him feel old. He was coming back a roundabout route via Miami but we arranged to get together after work a few days later in a winebar near the office-a place that had once been a cavernous Victorian pub and now had a split personality, with mean little chrome chairs that looked all wrong in the heavy pitch-pine booths. I thought, watching Jimmy go up to the bar, about him saying that he felt old. When he was so slender and vivid! Had I ever really tried to understand the ways in which a gay man's ageing might hurt differently from my own? The boy in fake Prada behind the counter was laughing up at him. Everyone liked Jim because he had an open face and a quiff of straw-colored hair, just like Tintin's. Of course, he didn't want to look like Tintin-he wanted to look like James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause.

I think you are looking a bit Dean-ish this evening, I said to him when we were settled. Those narrow, hot eyes, you know? Eyelids bruised from nights of excess?

Jet lag, he said. And what has you being so nice to me, Dame Freya darling? If this is a symptom of your midlife crisis, I hope you're going to go on having it.

What were you doing in Miami, dearest Mr. Chatwin? I said. You were hardly there for the fine wines.

You can't get a decent bottle of Sancerre south of the Mason-Dixon line, Jimmy said. Or even a good Chinese meal.

The best Chinese food in the world is in Seattle, I said, where the Chinese draughtsmen from Boeing open restaurants with their severance pay. They've got American raw materials there. That's what Chinese food needs.

You know the problem with Seattle? Jimmy said. It's too far away.

It's only too far away if you start from here.I disagree, he said seriously. There are some places that are too far away, even when you're in them. Seattle is one.

We talked this kind of nonsense a lot of the time. Roxy said it drove her crazy. But after twenty years together, Jimmy and I didn't listen to ourselves. We told each other everything through smiles or frowns or whether we cut a date short or lingered, or whether we looked down at the table or into each other's eyes, or whether we took a sip of the wine with gusto or flatly. Once, when I was upset at a meeting, Jimmy said, What's up, love? and Alex got really cross.

How do you know there's something up with her? he said, frustrated. How? The two of you always seem much the same to me.

There were ways in which we did acknowledge, in the winebar, that something was happening but that we had confidence in each other and would deal with it in time. That Jim ordered a bottle of wine, for example, instead of starting with a glass each, said to me that if I insisted on having a serious talk, he was there for me. And my mock-petulance when we were hugging goodbye told him that I wasn't going to be difficult about whatever he was up to in Miami.

Why can't I have a rendezvous with you? I said. Why can't I lie on a mattress in the pool of the Delano while a hunky waiter brings me a Cuba Libre and a slice of key lime pie?

Later, sweetie, Jimmy said. When we're old we'll move to South Beach for our arthritis.

I'll be jealous of all your geriatric rough trade, I said, rubbing his springy hair. That was the last time I ever touched him.

There'll be no rough trade left, he said. The boys will all be dead.

I had a funny story to tell him the next morning when I went in to work. Well, not all that funny, maybe. I'd been coming out of Euston Road station, going home from the winebar, when a pair of feet seemed to run towards me across the dirty pavement and stop, and a girl's voice said, Hi! I looked up and saw that behind her madly smiling face a video camera was pointed into mine. Fashion Channel Plus! the girl caroled, coming around shoulder-to-shoulder with me and beaming into the camera. It's the Vox Pop Shop! Hi! We're coming to you live from the streets of London to tell you what the happening people are wearing!

The camera with a man's legs walked backward and framed me. I'd looked to see what I was wearing. It was a charcoal wool trouser suit that had fitted when I was still smoking, but the pounds I'd put on since I quit poked out between the edges of the jacket now. I'd remembered that when I put it on, but I'd said to myself, Sure what of it, I'm only going to the office. Then I'd thought, That's a depressed woman's way of thinking. I am seriously depressed.

I don't know why you're asking me, I said to the camera, smiling pleasantly and pulling my stomach in. I'm afraid I don't know the first thing about fashion.

I expected to be contradicted, of course.

Leave it! the girl stunned me by shouting at the cameraman. This one's a no-no. She turned back to me for a moment. Sorry about that, she said over her shoulder. We're only talking to people who live here. Londoners.

That was all. No big deal. But I'd gone back to the basement stinging with chagrin. I live here! I protested in my head. I've lived in London since I was twenty years old! And that's a designer trouser suit-that cost a lot of money, so it did!

And there and then I'd picked a psychiatrist from the Yellow Pages and left a request for an appointment on his answering machine.

I was going to tell Jim all that.

It was the monthly planning meeting that morning. Alex and Roxy and I waited and waited. The phone rang. Alex put the phone down and said to us from lips gone chalk-white: Jimmy is dead. He had died, during the night, of a heart attack.

I never cried. My sister, Nora, who has managed to misunderstand me consistently from the hour I was born, rang me not long afterwards and said, You're getting over Jimmy very quickly, aren't you? I thought he was your big pal.

She'd taken against him, early on, because once when we stayed at her apartment, he thanked her by giving her a subscription to a Beethoven sonata cycle at Carnegie Hall with a little joke about showing the world she was not just a moneyed Mick. Nora is a big-deal personal assistant and earns a fortune and she's confident to a fault, but even she couldn't say what she wanted to, which was, What's wrong with being a moneyed Mick?

But the reason I did not cry was that I dared not.

I didn't know what to do. The first three or four days after he was dead I spent in the basement. I heard Alex calling down through the letterbox in the hall door and I heard my friend Caroline a couple of days later. But I shouted up to her that I was busy-that I was reading. I didn't come out till I had nothing left to read. I read all the paperbacks on the top shelf of the bookcase, from left to right, and then I read the whole of the Talbot Judgment because it was on the next shelf and then I read the guidebooks on the bottom shelves. After the funeral, I stopped reading and instead I wrote as much as I could. I wrote the pieces Jimmy had been scheduled to do as well as my own. I didn't stop moving and writing until I realized, in a crumbling spa in the Tatras foothills, that nothing was helping. Not the oxen dragging the old ploughs up to the small fields that survived on the hillsides, or the smell of woodsmoke and stabled animals along the muddy roads of the low villages as the cold evenings came down. It was no good being there without Jimmy to call to say that I had yet to see a vegetable or that I was reading the new Theroux and I disliked the man more than ever. Hello, it's only me. Hello, Only You. Where are you? I'm waiting outside the Minister's private office in a gilded villa. I'm having breakfast in a milkbar in a place I can't pronounce. Are you well? Do you have anyone there to talk to? I went to a god-awful folk-dance thing last night. The tourism bloke kept the penthouses for our group. How's Alex looking? The plane was diverted. I forgot to pack shades. Did you have the duck with red currants? The maize crop has failed and they're trying to get a World Bank loan. I have a toothache.

But back in London, I did not say that I was finished with the job. I didn't want to disturb the quiet we had pulled around ourselves. Alex sat in his boss's cubicle, and Roxy sat at her secretary's desk, and Betty the administration lady sat down the corridor in her room. I made as little noise as possible, working in the corner. We were gentle with one another. We tried not to mention Jimmy. One of his gym shoes lay on the floor under his desk. None of us put it away.

De Burca, I said to the psychiatrist's receptionist, when the day of my appointment came around. Kathleen de Burca.

She looked at me as if me not being called Smith or Jones was the very last straw, and put down her pen. Then she picked it up again, wearily.

Could you spell that? she said, as if it were entirely possible that I couldn't.

And what did I do? I said, That's Burke, in English, if that would be easier for you.

Then I complimented her on the New Age flower arrangement on her desk-fawning on her, because I was so afraid. The flesh on my cheeks was actually quivering with fear. By the time I went in to the psychiatrist's office with its antique furniture gleaming in the low light, I was not so much crying as sniveling. I thought everything might unravel then and there and I wouldn't be able to go on. I had let things be. I did my work, and let the rest pile up behind me. I was afraid he would move one little thing in my head, and the whole lot would crash.

There are tissues just beside the chair, he murmured.

I tried to tell him how desolate the nights had been for as long as I could remember. Yes, he murmured. Yes. I told him my best friend was a gay American man and he dropped dead and now I have nobody. Yes. My body slackened with the force of my crying. I howled. I'm getting old! I have made nothing out of my life! Yes, he said. Siblings? he said. A brother at home, and his wife and child, I said. And Nora in New York, the eldest. And my little brother Sean died when he was six and a half and if I'd stayed at home I might have been able to save him! More howling. And there were three or four babies who died around when they were born. Why do you mention them? he said. I don't know, I said. Except-my poor mother! I moaned and hiccuped, but then the storm of crying began to pass. I tried to explain to him: I'm too depressed to even dress properly. I was wearing a jacket the other day that doesn't even fit me! Units of alcohol? he was saying. I luxuriated in the safety of the exquisite room and his hands lying quietly on the desk, reflected in the polished surface. I did not pull myself up and sit properly, though now only the occasional sob shook me. If you could get it down on paper, he was saying, just the general picture, ages of the children at your mother's death, that kind of thing. Next time we meet I'll ask you-

And then I heard it. I wouldn't have, but that I had stopped crying.Someone made a furtive movement behind a screen in the dim corner behind him.

I sprang upright like a hare in the grass, and searched his face.

It is quite common! he said. Our trainees are allowed to monitor first consultations on exactly the same basis of absolute confidentiality as the primary relationship.

My legs were shaky as I walked to the door.

They do it in your country, too! he called after me. I can assure you!

That's how I know, I said to Nora when I phoned her, that he took the chance because I was Irish.

Nora was silent. She passionately believed in her own shrink. She'd been trying to get me to go into therapy for years. She'd even sent me a blank check once.

Maybe they do it to everybody, she began.

They don't, I said. You know they don't. If that was one of his own kind-if I'd been a university lecturer from Hampstead . . .

Come to me! she said. Come here! Or go home! I don't know how you stuck snobby old England all these years.

But I'd tried that before. The last time there'd been an upheaval in my life, I went to New York to stay with Nora, with the idea of maybe settling down near her. It lasted a week. And Ireland-well, I certainly wasn't going to live in Ireland. Though Ireland was on my mind, in a way it had never been before. Maybe going to the psychiatrist had stirred up the murk in my memory. Or maybe it was reading the Talbot Judgment again, though I hadn't realized at the time-so soon after Jimmy died-that I was taking it in.

Something had started moving inside me. I realized it standing in a private zoo near London, taking notes for a piece Alex wanted on animals as tourist attractions. It wasn't a zoo, exactly, as much as a species rescue place where they were running a breeding program to save the miniature lion tamarin monkey. The reddish-gold color of spaniels, the monkeys were, with ruffs like the MGM lion around each tiny, melancholy face. I leaned my forehead against the glass to watch them go about their business. I loved looking at them. They hung from branches by one arm, swinging slightly to and fro, pensive, or they crouched under the big fleshy leaves of the habitat, or they scratched their heads, completely indifferent to scrutiny. I followed the busy little doings of a lion-headed monkey about the size of my hand with an even smaller one clinging to its stomach. Mother and baby. Poignant little eyes, they had.

It struck me suddenly: I have never looked at my family the way I look at animals. I have never taken an unhurried look at the people by whom I was formed, wanting nothing but to see clearly, the way I look at animals or birds-appreciating them, without having any designs on them. My family has been the same size and shape in my head since I ran out of Ireland. Mother? Victim. Nora and me and Danny and poor little Sean? Neglected victims of her victimhood. Villain? Father. Old-style Irish Catholic patriarch; unkind to wife, unloving to children, harsh to young Kathleen when she tried to talk to him.

Then I lifted my head as if I could smell something odd.

What was I being bitter about, nearly thirty years after I'd seen my father last, and when he'd been dead five or six years? I couldn't not have changed. I could not be the same person now that I was when I left home. It just wasn't possible. Although I had lived for a long time, during the basement years, in a state of suspended animation, I had been alive. And everything that is alive changes all the time.

The mother and baby monkeys had disappeared. I think they'd gone in behind the big leaves of a tropical tree.

Where are you? I whispered. I tapped lightly on the glass.

The lines of a poem we learned at school came into my head and they pulled at me as I walked back to the car.

"Is there anybody there?" said the Traveller, knocking on the moonlit door-

There was a man knocking on the door of a deserted house deep in a forest. And there were ghosts inside on the stairs, weren't there? Listening to him.

"Tell them I came and no one answered-that I kept my word," he said....

I tried to remember it properly.

"Is there anybody there?" said the Traveller, knocking on the moonlit door, And his horse in the silence of the-something-champed the grasses of the forest's ferny floor, And a bird flew up out of a turret above the Traveller's head, And he smote upon the door again a second time. "Is there anybody there?" he said.

A picture formed at the back of my mind, of silent ghosts waiting and listening, and me, the Traveller, riding up and calling to them. Whether these were the ghosts of Marianne Talbot and William Mullan, watching each other on the lamplit stairs of Mount Talbot, or of my father and mother-his watch chain gleaming, her face a pale patch over his shoulder-I didn't bother to decide. It wasn't people I was thinking of. It was a shape, a blurred image-me outside somewhere, calling, and tragic ghosts listening to me and waiting for me to free them-that settled inside me.

Excerped from MY DREAM OF YOU © Copyright 2001 by Nuala O'Faolain. Reprinted with permission by Riverhead, an imprint of Penguin Putnam. All rights reserved.

My Dream of You

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 529 pages

- Publisher: Riverhead Trade

- ISBN-10: 1573229083

- ISBN-13: 9781573229081