Excerpt

Excerpt

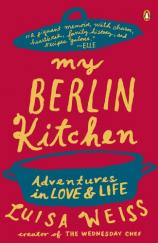

My Berlin Kitchen

Chapter 1: Never Want to Leave

I AM THREE YEARS OLD, SITTING ON A LITTLE WOODEN STOOL WORN BY years of use, right by the door to the kitchen. In front of me, on a small table that fits only three people, are a stack of newspapers, cookie tins, a woven basket full of cloth napkins, and a little ceramic dish, no more than an inch in diameter, filled with salt. My legs dangle from the stool and I face the stove.

Joanie, my Tagesmutter, as nannies are called in Germany, stands at the stove, melting butter in a pan. Joanie’s long curly hair is gathered up in a bun at the top of her head. Wispy curls frame her face and the heat from the stove gives her ruddy cheeks. Her kitchen smells, as it always does, of lemon peel and damp wood, of warmed cinnamon and aniseed and something crisping nuttily at the edges. Blue and white crockery lines the kitchen walls, while jugs and bowls and teapots are clustered on top of cabinets and ledges.

On the bulletin board above my head are photographs of Joanie’s three children, Nina, Nikolas, and Kim, and of me. In one picture, I am sitting under a tent made of bedsheets in Kim and Nikolas’s bedroom wearing pointed fur-lined slippers that are a hand-me-down from the older kids. Kim, just outside the frame of the camera, has me laughing so hard I can hardly breathe. He is six years my senior and the closest I’ll ever come to having a big brother.

Technically, I’m old enough to feed myself, but Kim still indulges me at lunchtime when he comes back from school, making elaborate takeoff, flight, and landing noises with each forkful he puts into my mouth. After lunch, we construct landscapes in his bedroom out of bedsheets and pillows and I submit happily to extended tickle sessions that always leave me gasping for air.

Joanie grew up in Washington, D.C., and in a sprawling apartment on Riverside Drive before moving to Berlin to study art as a young woman, which is where she fell in love with and eventually married a bearded young sculptor named Dietrich. She loves children and knows just how to talk to them, how to get them to fall in love with her, hook, line, and sinker. And in my eyes, Joanie is a goddess. She can do anything.

She sculpts busts of the maid she grew up with, her head thrown back in laughter, of her East German mother-in-law, of me, solemn-faced with a part down the middle of my head, and casts the busts in bronze that glows softly in candlelight. She makes dolls with long braids, soft limbs, and embroidered features. She sews tiny doll skirts and shirts and dresses out of fabric scraps and ribbon. She can bake bread and make flaky apple strudel. She knows all the words to beautiful folk and protest songs and when she sings, her high, clear voice always thrills me to the core. Joanie is pure love. She is love, safety, and comfort; sometimes it feels like my whole world revolves around her.

As the butter melts in Joanie’s little pan, I knock my feet together expectantly. A frothy swirl of beaten egg goes into the pan and as the sides begin to set, Joanie chatters away to me. “Om-lett-uh con-fee-tuuu-ruh!” she trills and I repeat after her, “con-fee-TUUU-ruh!” The beaten egg, palest yellow and airy, puffs up like a small cloud. Joanie flips it deftly and when it’s cooked through and light as air, she slides it onto a plate, dabs a stripe of raspberry jam down the middle, rolls it up, and dusts the top with a little powdered sugar. I love the way the cool, tart jam feels in my mouth as I eat the hot omelette.

After lunch it’s time for a nap in Joanie and Dietrich’s bedroom at the back of the apartment, down a long, book-lined hallway lit by a lamp in the shape of an enormous light bulb. The sounds of traffic on Hindenburgdamm mingle with birdsong and the voices of neighbors in the courtyard below. The alarm clocks on each side of the bed tick so loudly that I fall asleep with my heart beating like a metronome.

At the end of the workday, my mother, pixie-haired and smelling of lemony Eau Sauvage, will show up at the front door of Joanie’s apartment. She’ll come in, maybe stay for a cup of tea, but then she’ll tell me in Italian to put my shoes on and Joanie will laugh every time, sounding out my mother’s command. My mother and I speak Italian together, but Joanie and I speak English. These are the two languages of home for me: my mother and my father tongue. And in the world outside, there’s German.

I am old enough to know that I’m not supposed to show disappointment when my mother tells me it’s time to go home, but I never want to leave Joanie’s apartment, where it always smells of something good and there are promises of tickle sessions and pillow forts, where we listen to The Jungle Book on the record player and Joanie reads us Rudyard Kipling stories and when I do something to make her laugh, her laughter peals through the apartment. At home, life is quieter and more solitary. There’s a sadness in the air that I can’t yet understand.

But my mother says it’s time to go and I am nothing if not an obedient child. So I put on my shoes, say goodbye to Joanie, and walk down the two flights of stairs where a sign always affixed to one of the steps warns “Vorsicht! Frisch gebohnert,” though I’ve never seen anyone ever wax the floors, and my mother and I drive home.

It is the beginning of the 1980s. Reagan is president of the United States, the Red Brigades are terrorizing Italy, and a Wall encircles the former capital of Germany, built under the guise of keeping East Germans safe from the insidious force of capitalism, though it’s really meant to keep its people from hemorrhaging out into the world. And in West Berlin, in a third- floor apartment of an old building in a quiet leafy neighborhood rebuilt after large- scale destruction by Allied bombings in the waning months of World War II, I lie awake in my too-big bedroom, missing Joanie’s cozy, fragrant kitchen.

Omelette Confiture

SERVES 1

It may seem odd to pair eggs with jam, but the combination of sweet-tart

fruit with the moussey fluff of the omelette is delicious. It makes for a

comforting snack for a small child or a light breakfast for a sweet-toothed

adult. The best jams to use are ones with a tart bite: I’m partial to black or

red currant. And don’t skip the powdered sugar on top. The little explosions

of sugar on the tongue are what make this omelette special.

1 large egg

1 tablespoon milk

Small pinch of salt

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

1 to 2 tablespoons black or red currant jam

1⁄2 tablespoon powdered sugar, for garnish

1. Separate the egg white from the egg yolk. Beat the egg yolk with the milk in a small bowl until well combined. Beat the egg white with a pinch of salt in a spotlessly clean bowl until it just holds soft peaks. Fold the beaten egg white into the egg yolk mixture.

2. Melt the butter in a small nonstick skillet over medium heat. Pour the egg mixture into the pan and let cook for 3 minutes, until the edges have set, making sure the heat of the stove is not so high that the omelette browns or burns. Shaking the pan gently, flip the omelette and cook the other side for an additional 3 minutes. This takes some practice, but there’s no shame in using a plate over the pan to invert the omelette instead of flipping it.

3. When the omelette is set and cooked through, slide it onto a plate. Dab the jam along the center of the omelette and then roll up the omelette --- using a plastic spatula should help. Shake the powdered sugar through a sifter over the omelette and serve immediately.

My Berlin Kitchen

- Genres: Cooking

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- ISBN-10: 0147509742

- ISBN-13: 9780147509741