Excerpt

Excerpt

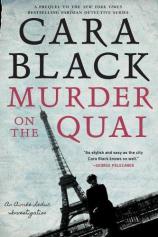

Murder on the Quai: An Aimée Leduc Investigation

Paris · November 9, 1989 · Thursday Night

Standing outside the Michelin-starred restaurant, a stone’s throw from the Champs-Élysées, the old man patted his stomach. The dark glass dome of the Grand Palais loomed ahead over the bare-branched trees. To his right, the circular nineteenth-century Théâtre Marigny.

“Non, non, if I don’t walk home I’ll regret it tomorrow.” He waved off his two drunken friends, men he’d known since his childhood in the village, as they laughingly fell into a taxi. Course had followed course; remembering the caviar-dotted lobster in a rich velouté sauce topped off by Courvoisier brandy, he rubbed his stomach again as he waved goodnight to the departing taxi. His belly was taut with discomfort; he needed to stretch it out before bed. Besides, he always enjoyed the walk home to his place on Place François Premier. Even now, after all these years, pride swelled in his chest that he had secured himself an address in le triangle d’or, the golden triangle, the most exclusive quartier in Paris. The thrill of living among the mansions and hôtels de luxe between avenues Montaigne, George V, and the Champs-Élysées never got old to him.

He looped his silk scarf tight, took a deep breath of the piercing chill November night. Belched. The born farmer in him sensed tonight would bring frost—a crinkled frost that would melt on the grey cobbles like tears. In the village, it would have been a hoarfrost blanketing the earth like lace.

He looked over his shoulder—force of habit—with vigilance that hadn’t diminished in forty years. They were always so careful, so scrupulous about the details, took pre-cautions—yet Bruno’s murder had scared them all. Made them wonder at the implications. Could it be...? But a month passed and nothing. Were they safe?

Not totally safe, not until the final trust document was rubber-stamped tomorrow. But that was only a formality. Nothing would go wrong this late in the game. He knew that—they all did.

Yet why had he woken up shouting in his sleep last night? Why did Philbert’s dentures grind so at dinner, and why did Alain drink a whole bottle of wine himself?

Brown leaves gusted against his ankles. On his right a blurred Arc de Triomphe glowed like a painting on a postage stamp farther down the Champs-Élysées. He kept a brisk pace, got his blood flowing, warmed up. He was fit as a fiddle, his doctor said, his heart like that of a man twenty years younger. A couple passed, huddling together in the cold.

Walking under the barren trees by the Grand Palais, he became aware of footsteps behind him. The footsteps stopped when he did. But as he turned at the intersection in front of the zebra crossing, he saw no one.

Nerves. The light turned green. He crossed. Midway down the next block he heard the footsteps again. Turned.

“Who’s there?”

Only a dark hedgerow, shadows cast from trees. Unease prickled the hairs on his neck. He walked faster now, looking for a taxi. Silly, he lived two blocks away, but he never ignored a feeling like this. Each taxi passed with a red light crowning the roof: occupied.

Stupid—why hadn’t he taken the taxi with the others? Kept to their protocol of precautions? His meal, rich in cream, sat in his stomach like a dead weight. Every time he heard the footsteps, he turned and saw no one. Paranoid, or was he losing his mind? Or was the brandy heightening sensations and dulling his reflexes?

Then a taxi with a green light slowed. He waved it down.

Thank God.

“Merci,” he said, shutting the taxi’s door, breathing heavily.

“I’m only supposed to stop at the taxi stand, monsieur.” “Then I’ll make it worth your while in appreciation.” He gave the address.

“But that’s only two blocks from here.” “Consider your fare doubled, monsieur.”

The taxi pulled away from the curb. He asked the driver to close his window.

But the driver ignored him. And turned toward the river.

Not the way home at all.

Ahead, streetlamps rimmed the quai, their globes of light reflecting yellow shimmers on the moving Seine. His heavy insides curdled.

“You’re going the wrong way.” The taxi accelerated, throwing him against the back of the seat. “Stop.” He tried the handle. Locked.

Afraid now, he pounded the plastic partition and tried reaching for the driver’s shoulder. The wheels rumbled down a cobblestoned ramp.

“Let me out.”

He didn’t even realize where they were until the taxi stopped. The taxi had lurched to a halt below the Pont des Invalides, nestled in the shadow of its arch support. Mist floated over the Seine, the gurgling water swollen by early November rain.

And then the door opened and before he could defend himself, his arms were pulled behind him. “Take my money, just take what you want.”

“You know what’s going to happen, don’t you?” said a voice.

He gasped. “Please, let me go.” “Don’t you remember the river?”

Panic flooded him. “Non, non. You must understand—it wasn’t supposed to happen...We can make it right.”

“Liar. Payback time.”

A rag was stuffed into his screaming mouth. His bile rose and all the rich food lodged in his gullet, choking him.

“You remember, don’t you? It’s your turn now.”

He was shoved to the edge of the quai and down into a squat. Through his blinding terror he saw one of his shoes fall into the water below. The lapping waves from a receding barge and the faint rhythm of faraway car horns masked his cry of pain. Even the lit globes of the sodium lamps faded into the mist on the cloud-blanketed night.

“How does it feel?” a voice hissed.

But he couldn’t answer as the sour-tasting gag tightened across his mouth. His tied hands gripped and flailed. He couldn’t breathe.

It wasn’t supposed to happen that way.

The shot to the back of his head was muffled by the plastic Vichy bottle used as a silencer and the rumble of the traffic overhead.

Paris · November 10, 1989 · Friday Afternoon

Aimée Leduc gazed in horror at the mess in her test tube in the école de médecine lab. Her experiment ruined. Again.

She held the tube to her nose and sniffed. Bleach. Someone had sabotaged her work. Probably one of her twelve fellow premed lab mates—all of them under twenty, like Aimée; all of them male.

The professor was heading her way.

“This is the second time this month, Serge,” she said, panicked.

“Didn’t I warn you?” said Serge, an upper-class lab assistant, lowering his voice. “Around here you have to guard your tubes and petri dishes with your life. It happens.”

Yes, but that didn’t make it fair. She wanted to shout, to accuse someone. It was well known that only 15 percent of students would be allowed back for the second year. The cutthroat competition led some students to sabotage others just to stay in the running.

“Don’t forget this assignment goes toward your semester grade,” Dr. Fabre, their instructor, was saying as the lab emptied.

What could she do?

She liked Dr. Fabre, an older man with tortoiseshell glasses and a slight stoop. His lectures had a strange but appealing energy. Now he asked, “A problem, Mademoiselle Leduc?”

“Someone poured bleach in my test tube...” Merde. She didn’t want him to think she was the type to whine.

Dr. Fabre shook his head. “No other students had this issue. Do you expect special treatment? Instead of blaming your errors on others, check your notes.”

“But Dr. Fabre, you can smell it...”

“So you say, Mademoiselle Leduc. But if it means so much, you should have watched your work more carefully. Perhaps slept here. I did in my premed days.”

No sympathy here. They wanted to be doctors and help people—why not start with themselves?

She could cope with grueling exams, reports, and all-night studying. But this? She bit her lip, determined not to cry.

“Professor, would you please let me redo the experiment? I’ll have the results by tomorrow morning.”

“I’ve got four classes to grade and my schedule’s full. It’s not fair to the others, mademoiselle.”

Or to her, but it seemed that didn’t matter.

“Let me warn you,” he said. “We expect the best. Despite the promise you’ve shown, you’re a candidate for the suspension list. Consider this a formal warning.”

Her heart dropped. “There must be a mistake.” She riffled through her bag and pulled out her notebook, where she kept duplicates of her assignments and grades. The same notebook with the surveillance case notes she’d been transcribing for her father. “Sir, I scored in the top ten percentile, and I turned in all my assignments.”

Dr. Fabre shook his head. “As so have many others. I can’t make exceptions.”

She managed a nod before she humiliated herself further, and to refrain from kicking the door as he exited.

She rolled up her lab coat sleeves and cleaned the lab in the coffee-colored light of the dank November afternoon. It was her turn to be the first-year grunt. At the faucet she scrubbed her hands with carbolic soap, trying to figure out what to do. The formaldehyde smell permeated everything. Her shoes, her clothes. She couldn’t even shampoo the smell out of her hair at night. Another thing she’d chalked up to life in med school.

Serge came in, handed her a paper towel, then leaned against the counter where the surgical instruments dried.

“First year’s the toughest. You’ll get over it. Everyone does, Aimée.” Serge had the beginnings of a beard, thick black hair and myopic eyes behind black-frame glasses. “I was a carabin, too.” A stupid archaic term still used for med students, because their lab uniforms resembled those of les carabines, riflemen in Napoléon’s army.

“I expected a grind, but backstabbing?” She wanted to spit. “You heard Dr. Fabre. I’m going to fail.”

“Pah, you’ll make it. It’s all about the exam, no matter what he says. You work hard,” Serge said. “Be patient.”

Patient, her? It was all she could do to focus. From day one, the competitiveness, that feeling of never measuring up, had dogged her. Every morning she told herself she could do it—couldn’t she? After all, she’d made it into med school.

Her gaze out the narrow lab window took in the gunmetal sky over the medieval wet courtyard of l’école de médecine. Students bent into the November wind. Nine more years of this if she passed. Maybe ten.

“You’ll see it’s worth it when you find your calling. I hated my first autopsy, threw up,” said Serge. “Almost left medicine. But the next involved a homicide victim. The policeman asked the attending examiner questions. How he looked at the body for clues to solve the murder fascinated me.” Serge shrugged. “That’s when I learned that the dead talk. I’m learning how to listen.”

“But it’s the living I’d rather figure out,” she said.

Serge took off his glasses, wiped them with the hem of his lab coat. “I’ve been accepted into Pathology after my rotation.”

She smiled, happy for him. “Congrats, Serge.” Serge shrugged. “Take a walk. It will clear your head.”

She hung up her lab coat with LEDUC stitched on the lapel. The old-style thirties script reminded her of the Leduc Detective sign hanging over her father’s office on rue du Louvre. She kicked off her scuffed clogs and stepped into her worn Texan cowboy boots, put on her leather jacket, and shouldered her bag.

“Aimée, what about your late lunch? We’re heating up the croque-madame.”

“All yours. Knock yourself out.”

She waved at Serge. She’d lost her appetite.

Near the study lounge where everyone hung out between lectures, she looked for tall, blond Florent. They’d met at the study group, almost two months now. She wanted to lean on his shoulder. No, face it—she wanted to do a lot more than that. Crawl under the duvet with him, like the other night. The morning after, brioches in bed, skipping study group to lick off the buttery crumbs. Murmurs of a weekend in Brittany at his aristocratic family’s country home.

She didn’t see Florent among the loitering undergraduates. Time for a pee.

After checking the whole row of bathroom stalls, at last she found one with toilet paper and latched the door.

The hall door opened—voices, footsteps. The squeal of the faucet.

“Why didn’t you tell me before? I love clubbing at Queen,” said the nasal voice she recognized as Mimi’s. Florent’s sister was a third year. Tall and big toothed, Mimi reminded her of a horse. Water gushed from the faucet and she heard snickers. Aimée flushed, pulled up her agent provocateur tights and headed toward the sinks.

“I want to go with you, but Florent’s engagement party is this weekend,” said Mimi.

Aimée blinked. Florent’s engagement party? She and Florent were supposed to be going to Brittany.

“I thought I recognized those cowboy boots,” said Mimi, turning toward her. Her voice lowered as if in confidence. “I just felt it was right to tell you that I don’t think your weekend plans with my brother are going to happen.”

At the soap-splashed mirror Aimée finger-combed her spiky hair and dotted Chanel red on her trembling lips. Her mouth was dry. Mimi’s friend, the Queen clubber, eyed Aimée with a predatory gaze.

“Why’s that, Mimi?” Aimée said finally. “He’s getting engaged this weekend.”

Breathe, she had to keep breathing. “Florent didn’t tell me . . .”

“I’m telling you, compris? No idea what he was thinking leading you on, but this engagement has been in the works for eons.” Mimi laughed. “Florent’s inheriting a title. You think my family would let him get serious about...?”

A knife twisted in her gut. Could it be true? He’d never mentioned an engagement.

“Don’t take it hard. You’ll get over it. Just don’t kid yourself.”

“And you’re his messenger service?”

Mimi sighed as she drew in brows with an eyebrow pencil. “Désolée. He didn’t want to hurt your feelings.”

Was it that Mimi and her crowd hated her and were just being nasty? Or was Florent a gutless wonder who couldn’t tell her face-to-face? Maybe both.

“Non, I need to see him.” She turned and stared at Mimi. “He needs to tell me himself.”

“Don’t say you weren’t warned.” Mimi snapped her makeup case shut. Noises echoed in the corridor as she opened the bathroom door and left, followed by her friend. “Seriously, let’s go clubbing,” she was saying as the door closed behind her.

Out in the corridor Aimée had to pass by Mimi and her group of laughing sycophants, who were blocking her way and shooting her looks. Her face reddened. She wanted the creaking wood floor to open up and swallow her. A loser. She’d die if her friends heard, and they would—Florent was supposed to come to her best friend Martine’s birthday party.

Waves of humiliation washed over her. She should have known that Florent, an aristo from the posh Neuilly suburb with de in his family name, had been slumming with her. She’d been naïve to trust him, the spoiled bastard. For God’s sake, she’d slept with him. His feelings for her had probably been bogus like everything else about him. Except for his prospective title.

Furious and blinking back tears, she ran down the stairs and through the twisting medieval maze of the seventeenth-century building. The hallways were glacially cold, with dust in the corners. A dead quiet clung to the tall glass anatomy displays of skeletons and bones. She hated the whole damn place.

Coming into the chilly cobbled courtyard, she zipped up her leather jacket, looped her scarf, and pulled on her gloves. Her pager erupted in her pocket. Florent with a kiss-off?

But it was from her father at Leduc Detective. Strange, he never paged her.

His office was ten minutes away and she could use the walk. She passed the pillars enclosing the garden sculptures of École des Beaux-Arts, continued along the quai Malaquais, its misty banks burnished gold in the light of the streetlamps, and crossed the Pont des Arts, pushing aside the memory of sharing midnight Champagne here with Florent. The Seine swirled below, green, black, and turgid. The bateaux-mouches slid, twinkling, into the dusk. She hurried now, pulling her collar up against the chill, through the Louvre’s shadowed Cour Carré.

By her father’s office, she stepped into the warm corner café, whose windows were clouded with moisture, and nodded at Virginie, the proprietress. The staticky radio news channel blared, mixing with a whooshing of the milk steamer.

The local butcher, a rotund man wearing a white apron smeared with blood, set his demi-pression de bière on the counter. “Tell le vieux I’ve got that lamb shank he ordered.” His boucherie was around the corner, its storefront crowned with the traditional horse busts.

“Merci,” she said.

Le vieux, her grand-père, had founded Leduc Detective after years at the Sûreté. His private detective agency made use of his contacts and connections to specialize in missing persons. “One of the top five agencies,” he’d always say. “I’m discreet and get results.”

The butcher liked to talk. “He’s quite the gourmand these days, eh, your grand-père?” He drew on his beer. “Semi-retirement? One like him never retires.”

He’d got that right, according to her father, who’d taken over Leduc Detective after he left the Paris Police. Grand-père had run a one-man show at the detective agency until then. He had officially retired to make room for his son, but kept many fingers in the pie. Too many, Aimée’s father often said.

“Tell him I’ll save some beef cheeks. I know he likes them.”

Sounded like the butcher missed her grand-père and his business.

“In the continuing historic news from Berlin,” said the announcer’s voice coming from the radio behind the chipped melamine counter, “on this cold afternoon, for the first time in twenty-eight years, crowds pass beyond Check-point Charlie after the Berlin Wall fell last night...” The rest was lost in crowd noises.

“Can you believe it?” said the butcher, rubbing his hands on his apron. “That’s the end of Communism and I just paid my Party dues.”

The wire birdcage of an elevator in her father’s building on rue du Louvre sported an Out of Service sign. When was it ever in service? She picked up the mail from the concierge—bills. The winding stairs were redolent of beeswax polish. She was still trudging up to her father’s office on the third floor when the timed light switched off, plunging the staircase in darkness, and she almost stumbled. Feeling her way up the smooth banister, she managed to reach the landing and hit the light. Leduc Detective’s frosted-glass door was open. Odd.

“Papa?”

Stepping inside, she heard his muffled voice. Drawers closing. The old wood-paneled partition blocked her view.

She hung up her leather jacket but kept her scarf on. Her father’s nineteenth-century office, with its high ceilings, carved wood boiseries, and nonfunctional marble fireplace, enjoyed nineteenth-century heating. She rubbed the goose-bumps on her arms, then gave the radiator a good kick. Sputter, sputter . . . et voilà.

On the wall were old underground sewer maps that had fascinated her as a child. Still did. She set the bills below the old sepia photo of her grandfather during his Sûreté days, waxed mustache and all. Next to it on the wall was Leduc Detective’s original business license.

“I kept my distance, as requested, Jean-Claude,” a woman was saying. “I asked for nothing. But we’re still family, and now I need your help.”

Family?

Curious, Aimée peered around the screen. She saw a woman sitting across from her father at his mahogany desk. She was in her mid-forties, with broad cheekbones and short, brown hair. A mink-collared coat rested in her lap. Wide-set eyes blinking with unease, she reminded Aimée of a deer. A frightened deer.

Who was this woman?

Her father looked up at Aimée, his reading glasses riding down his nose, his dark brown hair curling over his suit jacket collar. His expression was both irritated and quizzical.

“You paged me, Papa. Something come up?”

Her father sighed. “My daughter, Aimée, Mademoiselle Peltier.”

“No need for the formality, Jean-Claude.” The woman reached out to shake Aimée’s hand. “I’m Elise, your father’s second cousin. We met but you were small.”

“We did?” Who knew she had this distant relative? “You were a toddler.” Elise gave a small smile.

Aimée’s heart dropped. “Then you must have known my mother.” Her American mother, who had disappeared when Aimée was only eight years old, leaving Jean-Claude to raise their daughter alone.

“That’s not why Mademoiselle Peltier’s here, Aimée,” said her father. His mouth was tight with anger. “Elise, I’m packing,” he said. “My train’s in an hour. I know someone very good who can help you.”

“Mais you’re family,” Elise said, insistent. “You’re a former policeman. Without your help I’ll never discover the truth.”

Aimée shot her father a what-in-the-world look. He averted his gaze. Was he hiding something? She couldn’t remember the last time she’d seen her father so uncomfortable.

Elise turned back to her. “As I was telling your father, my papa was murdered. He was found tied and bound, a bullet in the back of his head, under Pont des Invalides.” Elise twisted her Hermès scarf between her fingers.

Aimée tried not to betray her shock. She’d followed the story in Le Parisien, every lurid detail. She knew the spot, the dock for the bateaux-mouches—a busy place. “Wasn’t that a few weeks ago? Did the case get solved?”

Elise’s lip quivered. “It’s been a month and the police have discovered nothing. My mother’s gone into a shell, won’t speak or eat.”

Aimée tried to catch her father’s eye.

“Again, I’m sorry, but my field’s missing persons, Elise.” Her father slid files in his briefcase.

How could he act so cold—so businesslike—with his cousin?

“Papa still had money in his wallet, his keys.”

“That’s right, the article said nothing was missing,” said Aimée. She remembered reading that a fisherman had found the body early the morning after. “He wasn’t a rob- bery victim.”

Elise nodded. “Why? That’s what I want to know. Who’d do this?” Her voice cracked. “The police say they have explored all avenues. Even after I showed them this. I found it in Papa’s coat pocket.”

Curious, Aimée glanced over as Elise set an open match-book on the desk. In it was written SUZY and a phone number.

“Can you find her, Jean-Claude?”

“Why do you want to find her?” her father asked. Aimée recognized that question he used to divert spouses from pursuing un amour best left alone.

“Who is Suzy?” said Aimée.

Elise rubbed her eyes. “You remember Papa, non, Jean-Claude? He’s not the type to have a mistress, but now I’ve got my doubts. What if he got mixed up in shady business at a club, you know?”

Aimée picked up the matchbook. Le Gogo was emblazoned in gold on the cover.

“Le Gogo’s off the Champs-Élysées on rue de Ponthieu, non?” said Aimée.

Elise nodded. “You know it?” Aimée shrugged. “Know of it, oui.”

A quartier of boîtes de nuit, discos and clubs like Queen, Rasputin, and Régine’s for la jet-set, at least until a few years ago. Places Florent’s sister, Mimi, clubbed at.

“Jean-Claude, I’ll hire you to investigate. Do this for me, please? Find this Suzy and see if she had anything to do with his murder.”

“Haven’t you called this number yourself?”

Of course she had, Aimée thought, catching her father’s eye.

“A man answered and I hung up.” Elise looked beseechingly at Aimée’s father. “The police have gotten nowhere. But one of the inspectors, a Morbier, told me you would help. Then I realized he was referring me to you, Jean-Claude. My own family.”

Morbier was her father’s first colleague on the beat, and Aimée’s godfather. He must have felt sorry for Elise. What she didn’t understand was why her father appeared so reluctant to help.

She opened her mouth to speak but caught her father’s

be quiet look and the slight shake of his head.

“Elise, pursuing this could lead to discovering something that might hurt your mother,” said her father. “An indiscretion you wish you didn’t know about.”

Elise’s eyes welled. “That’s what the police say, what everyone says. But it’s not right.” She erupted into sobs. “Papa wasn’t like that. Maybe everyone says that, but he really wasn’t the type to go to these clubs.”

But she was ignoring the evidence in her hand, Aimée thought. The man must have led a secret life.

“He was murdered in cold blood. Shot on the quai.” Her lip quivered. “But no one cares, they’re indifferent, no one wants to help—not even you. It’s like it never happened.”

“The police have their procedures, Elise. They’re not indifferent; they follow clues. Check evidence. This murder may have been random, the most difficult kind to solve. Morbier must have told you that.” Jean-Claude passed her a box of tissues. “I’m sorry. Truly sorry.”

“The certificat de décès came today.” She blew her nose. “I don’t know what’s worse: seeing it in black and white and not being able to do anything, or seeing my mother wasting away to nothing.”

Elise set the report on the pile on Aimée’s father’s desk. The radiator sputtered.

“Jean-Claude, I’ve written down everything I can remember. Plus there’s a copy of the police statement. Please. It’s all here.”

Her father nodded. Scanned the statement.

“I’ll do it the minute I get back,” he said. “But only to find clues to turn over to the police, you understand?”

In answer Elise pulled out her checkbook. “Will that do for a retainer?”

Five thousand francs. Aimée’s eyes bulged.

Elise blew her nose, wiped her eyes, a mascaraed mess. “Elise, there’s a WC down the hall,” said Aimée, shooting her father a look.

Her father slapped a report into his briefcase, buckled it closed. “Aimée, I know you go back to the lab on Friday nights,” he said. “But Sylvie’s still out with la grippe.” He gestured to his secretary’s desk. Reports piled high around a wilting dahlia plant. Poor Sylvie, sick like tout le monde.

“Hate to ask, but could you put in an hour and organize things? Handle calls from the answering machine while I’m gone?”

This was the last thing she wanted to do. She had so much on her mind—she had her place in the premed program to save.

“That’s why you paged me?”

Again he nodded. “Two clients haven’t settled their accounts,” he said with a sigh. “It’s tight this month. That’s why I’ll take her case.”

The curse of the business. As a private contractor, he was always the last to get paid. But how could she refuse to help? “Bien sûr.” She tapped her boot heel, surveying his secretary’s cluttered desk. But now there was something she needed to ask him. She swallowed hard. “Papa, Elise remembered me from when I was little. Did she know Maman?”

For a moment, pain shone in his eyes. “It’s been fifteen years. Elise and I were never close.”

And where her mother was concerned he ignored the question.

As usual.

But she wouldn’t let him off this time. “What about my mother?”

“We don’t talk about the past, Aimée.”

She steeled her nerves, aware this was painful for him, too. “It’s time we do. I want to know if my mother’s alive. I want to know about my relatives.”

“Not now, Aimée. Leave it alone. Trust me on this.” “She’s still family, Papa. A blood relation.”

He glanced at his watch.

“Something come up all of a sudden?” she asked. “You could say that. If I don’t leave I’ll miss my train.” “Train to where?”

He had packed an overnight bag, she saw. “Alors, Gerhard called from Berlin.”

Now Aimée remembered his contact there and the news bulletin on the radio. “Berlin? But the Wall’s just come down. Why now? You think it’s safe?”

“Safer than ever. I need to get hold of those Berlin files in person . . .”

Hadn’t she transcribed his investigative notes on a German couple last week? “You mean the missing husband?”

“Exactement. Before the Stasi destroy all the records.” He rubbed his forehead.

Elise would be back from the bathroom any moment. Aimée didn’t want to let the woman get away without hearing what she had to say about Aimée’s mother. On impulse she said, “Let me follow up on this Suzy. I read all about the case, Papa.”

“Aren’t you a first-year med student with exams coming up?”

Aimée pointed to the mink-collared coat draped over the back of the chair. “Didn’t you say it’s tight this month?”

His mouth pursed. “Not a good idea, Aimée.” Now he thought it wasn’t a good idea for her to help— now that it was something interesting. He’d been happy to ask her to organize his files and answer his phone messages. “A piece of cake, Papa. Not even an evening’s work. You always tell me to follow my instinct. I can do this in my sleep.”

She’d been raised by two police detectives, her father and her grandfather. She’d spent her childhood dozing in the backseat of the car while her papa was running surveillance, and her teen years keeping the pot warm on the stove for him when he was out on all-night stakeouts.

“Remember last year when I helped you track down that

fille at the disco because you were too old to go in?”

An aristo’s underage daughter who’d run off with a Corsican gangster.

“This is different, Aimée.”

“How? You’re just saying that. Look, it’s a simple job of asking around at this club and giving Elise some closure, c’est tout.” As she said it out loud, she wondered why the police hadn’t just done the same thing—it sounded straight- forward enough. “Did Morbier refer her because his hands are tied?”

“Something like that.” He’d bent down to pick up his case and she couldn’t see his expression. “Don’t you have a lab write-up to do, Aimée?”

Changing the subject, as usual. “Not exactly,” she said.

She felt like a six-year-old again—getting in trouble on the playground. How could she tell her father when he was running to catch a train? Face his disappointment?

Her papa cupped her chin in his warm hands. “What’s up, ma princesse?”

Why did she always forget how well her father knew her? “My lab experiment was sabotaged, Papa. It’s so cutthroat. I might get suspended even though I’ve done the work.”

Her father snorted. “That’s going to stop you? Nothing worth doing comes easy.” He winked. “You’d let them intimidate you? Where’s my fighter?”

That’s all he could say? On top of it, her boyfriend was getting engaged. Her life had fallen apart.

“Don’t disappoint me, Aimée,” he said, his tone turned serious. “I want better things for you. To be a doctor—have a respected profession, meaningful work—that’s so important.”

Translation: It was important for him. He didn’t want her to follow in his footsteps, and especially not those of her mother—an American free spirit who couldn’t cope with being tied down to her family and who’d broken his heart. But Aimée’s memories of her mother were warm and fuzzy— chocolat chaud and madeleines and stories at bedtime.

“How are we related to Elise and her family? Why didn’t I know they existed?”

“We’ll talk when I get back.”

She let out a groan. “You mean I have to ask Grand-père, is that it?”

Her father shrugged.

Not again. “You’re still not speaking to him?”

Her father reached for his wool scarf. “He’s not speaking to me. But he’s the one to ask about that side of the family.” Fine. She would. “Well, we can solve Elise’s mystery for her and put the check in the bank. We both know her father had an affair—cut and dried. I’ll check out this Suzy this weekend and then write up a report.”

Simple. Then back to the grind of the textbooks.

“For once listen to me. You’ve got an exam coming up,” said her father. “That’s the priority. Concentrate on studying, that’s your job.”

“Papa . . .”

“Not now, Aimée.” His expression was full of sadness, misgiving, and urgency, all at once. “There are some things you should know. We’ll talk when I get back.”

She hadn’t seen that look on his face since that day when she was eight years old and she’d come home after school to find a note on the door in her mother’s handwriting: Stay with the neighbor. It was the last she’d ever heard of her mother.

“What’s wrong, Papa?”

He was about to speak, but the door’s buzzer sounded and he glanced at his brown leather watch. “That’s the taxi.” He gave Aimée a hug, enveloping her in the scent of his wool overcoat and pine cologne. Kissed her cheeks, leaving a warm imprint.

“I’ll call you from Berlin.”

She wished she’d had enough time to drag it out of him, whatever it was.

Halfway down the winding stairs, he called up. “Don’t forget what I said. Hands off. And reserve the van for the Place Vendôme surveillance.”

Elise returned from the bathroom, mascara and eyeliner carefully reapplied around her doe eyes.

“My father’s left for Berlin,” Aimée said. “He’s sorry, he meant to say goodbye.” She rushed on, “Elise, did you know my mother?”

Elise’s eyes widened. “Yes, l’Américaine.” Aimée’s pulse thumped.

“So you do remember her?”

“Yes, I think we have some photos.”

Photos? Aimée didn’t even have one—her father had burned them all. “I’d love to see them. Learn about my family.”

The radiator sputtered.

“Of course. They’re somewhere. I’ll need to find them. Right now, I can’t leave my mother. I’m afraid she’ll hurt herself. She’s talked of suicide, she hides her pills.” Elise’s mouth quivered. “My father’s murder’s taken over our life.”

If Aimée found Suzy, distraught Elise would want to pay her back by finding those photos. Give and take, do a favor and get one in return—didn’t it work that way?

“I’ll find Suzy, Elise.”

Elise took her coat, then Aimée’s hand. Her wide-set, red- rimmed eyes welled again. “Merci for your offer. So sweet. Your father’s honorable and I’m sure that’s true of you, too. But I need his help.”

Aimée’s heart fell. She smiled through the sting of her disappointment. “We’re family, Elise. In case you need any- thing, here’s my card.”

She kicked the radiator until it sputtered to life. Then again for good measure.

She looked at Sylvie’s desk—she should get started on that. It would take her mind off her looming academic suspension.

Her hand hovered over the phone as she debated whether to call Florent and ask him about this weekend. Maybe she’d misunderstood.

Fat chance.

No doubt his horse-faced sister had enjoyed following her into the bathroom and dropping the bad news—putting Aimée in her place. Meanwhile, Florent was taking the cow- ard’s way out.

Forget calling Florent. She’d make him deal with her face to face at next Tuesday’s lab class. In the meantime, screw him.

In two hours she’d finished logging and sorting the inbox, followed up on the outbox, filed dossiers, and typed her father’s notes. If only her father had let her computerize their system, she could have accomplished it all in under half an hour.

She wished she had time to go back to that computer course she’d taken over the summer.

Her eye caught on Elise’s folder, the generous check.

Could she tie that up tonight?

Didn’t her father always say you can’t make a goal unless you kick the ball?

She rooted around in the file cabinet until she found her father’s notes from a similar case to Elise’s—a widow who had been investigating her late husband’s illicit affair. Aimée studied them. Simple.

She’d make a list of key points from Elise Peltier’s notes— that was always the way her father built an investigation. Then add details from the police report to create a brief profile.

Bruno Peltier, aged sixty-seven, of 34 rue Lavoisier, retired, discovered in the early hours of October 10 on the quai under the Pont des Invalides. Gunshot wound to the back of his head. He’d last been seen leaving his residence on foot at 8 p.m. for a dinner with old friends at Laurent, a posh restaurant off the Champs-Élysées in the old Louis XIV hunting lodge.

When he hadn’t returned home by 3 a.m., his wife called one of the friends he’d been dining with. The friend’s name was not in the police report or in Elise’s notes. Bruno Peltier had never shown up at the restaurant, the friend said to his wife: they’d figured he had the flu. The police were called to the quai after a fisherman found him at dawn with his wallet and ID.

Not much.

She called Suzy.

The number rang and rang.

“Oui?” said a man, breathing heavily as if he’d come up the stairs.

“Have I missed Suzy?” “Who?”

Now what could she say? Think, she had to think. Come up with something plausible.

“Excusez-moi, monsieur, but Suzy gave me this number.”

“Et alors?”

“I borrowed money from her on rue de Ponthieu a few weeks ago,” said Aimée. “I want to return it.”

“Ah, you mean . . .” Pause. “I see.” See what? “Is this a public phone?” “What’s that to you?”

Helpful, this man. “So where can I reach her?” “Comes and goes. I don’t monitor the tenants.”

So Suzy rented. This was probably a public phone in the hallway. “What’s her last name?”

“Don’t you know it?”

She reached in the secretary’s desk drawer for the petty cash box. She checked the amount—enough for a bribe? Her father would shoot her. She had no idea what he needed to pay his informers. Then again, she could replace the petty cash and then some with Elise’s check.

She pulled a petty cash receipt off the pad and started filling it out. Eight hundred francs, more than a nice evening out with wine, should do the trick.

“Look, I’ll just drop the money off, leave it with you. Give me the address . . .”

Money. According to her father, it worked most of the time. And saved a lot of standing around in the cold for hours. At least she hoped it would.

This could be fun, she thought, checking her mini sur- veillance tools, which she had fit into her makeup kit: lock-picking set (just in case), tweezers (always handy for a stray eyebrow or a sliver-sized piece of evidence), waxed thread (useful for stitching a hem or tying slingshots), nail polish (to stop a run or to mark territory), and, for key impressions, putty she hid in her blush compact. From her father’s collection, she chose the palm-sized light-weight camera and extra film.

Gauze-like evening clouds zigzagged over the Louvre as she ran to the Métro. Shouldering her secondhand Vuitton carryall—a summer score from the flea market—she hopped on the second-class car, pulled out her anatomy textbook and highlighter, and tried to read. Five stops later she noticed the woman next to her, a sophisticate in a black YSL trench and pearls, had fallen asleep. Aimée nearly had, too.

A short walk under the bare-branched trees on the brightly lit Champs-Élysées, then a right past the tiny art cinema, Le Balzac, one of her premed Friday night haunts; down narrow, winding rue Lord Byron, named for the poet who, according to her grand-père, had never set foot here. Off rue Washington, she found Suzy’s address by walking through a tall carriage entrance that led to Cité Odiot, a grassy enclave bordered by towering plane trees. An island of calm. She breathed in the damp leaves, heard twittering birds in the hedge. Such an oasis, three blocks from the jammed, busy, yet seductive Champs-Élysées and the death- trap roundabout of the Arc de Triomphe.

This quiet, dimly lit green enclave, surrounded on both sides by rose and cream buildings, extended half a block. Exclusive and hidden. At odds, she thought, with the peeling stucco of the leprous gatekeeper’s loge.

A quick scan of the names on the row of mailboxes and she spotted a label that read S. Kimmerlain/R. Vezy.

Could that be Suzy? She reached in with pincered fingertips and came back with a France Telecom ad flyer addressed to Suzy Kimmerlain, #402. She pulled out the camera from her leather jacket pocket and snapped. Always document everything—her father’s dictum ran through her head.

She felt like a secret agent in those old spy movies.

The gatekeeper poked his head out of the loge. She didn’t need his help now. To avoid him she slipped behind a column and then ducked into the stairwell. The climb to the fourth floor—narrow winding stairs, like in a medieval tower—would give anyone a workout.

Neither door on the landing held a nameplate. No one answered at the first. At the second, a woman with her head wrapped in a towel cracked the door. A green gel mask covered her face.

“Oui?”

“Suzy?”

“If you’re selling something, I don’t want any.” “Please, Suzy . . .”

“She’s gone to work,” the woman interrupted. Great.

“But I owe her money,” said Aimée, sticking with her earlier improvisation. “She told me to bring it here.”

“Vraiment?” A shrug of the pink bathrobe-clad shoulders. “Leave it with me.”

Did she look stupid? Aimée shook her head. “In person, she said.”

The kettle whistled. Over the woman’s shoulder Aimée could see a narrow chambre de bonne. A bare-bones accom- modation, a former maid’s room, in a quartier luxe, only a few blocks from where the wealthy Monsieur Bruno Peltier had lived.

“Wait a minute. You’re the one she talked about, non? You used to work together?” Aimée nodded. “That’s right.” “Then go find her at work.” The woman started to close the door. Merde. “But I went and she’s not there,” she lied.

The woman expelled a rush of air as if Aimée were slow. “Try the Alibaba.”

The door shut in her face.

If Papa had said it once, he’d said it a thousand times: “Ninety percent of surveillance consists of tedious plodding and persistence.” Find a name, a location, and follow up. Keep following up until you find a thread, a path leading somewhere. As he once said after a long night’s surveillance, “Investigating is just not going away.”

He tried to make his work sound boring, but she carried boredom in her rucksack in a biology book.

So far she’d found Suzy’s full name, her address, and gotten the name of her current employer, all in exactly forty minutes. Now she needed to record it all, write it into a report and log billable hours.

Totally manageable.