Excerpt

Excerpt

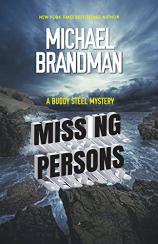

Missing Persons: A Buddy Steel Mystery

Chapter One

A scorching heat wave blanketed the West Coast, bringing with it record temperatures, rolling blackouts, and a general feeling of malaise that infected everyone.

A fast-moving Mexican monsoon, however, was now gaining strength in the Gulf of Mexico, steaming up the California coast accompanied by gale force winds and heavy rain.

It would most likely reach Freedom by late afternoon. I sat staring out the office window, elated that the storm would finally end the stultifying heat, but also apprehensive of the possible havoc it might wreak.

“Global warming,” I thought.

A late model green Toyota Camry pulled up in front of the San Remo County Courthouse. I watched as a middle-aged woman emerged, looked around, then headed inside.

After a few moments, I heard Sheriff’s Deputy Johnny Kennerly talking with the woman. Then he appeared in my doorway and stood there, fanning himself with a legal size yellow pad.

“There’s a Rosalita Gonzalez here to see you.”

I swiveled my chair around to face him. “What about?”

“You mean what does she want?”

“Yes.”

“She wants to see you.”

“So you said. What does she want to see me about?”

“I didn’t ask.”

“You didn’t ask?”

“I’m a Deputy Sheriff, not a personal assistant.”

“You had me fooled. I guess that means a donut run is out.”

Johnny fanned himself faster. “Funny,” he said.

I soldiered on. “So you don’t know why she’s here.”

“Correct.”

“Do you find that at all strange?”

“No.”

“I find it strange.”

“And I should care about that because?”

I gave him my best dead-eyed stare.

“Would you like me to show her in?” Johnny asked.

“Only if it meshes with your job description.”

Johnny stopped fanning himself and grinned. “I’ll have to check my contract.”

He went to get Rosalita Gonzalez, who followed him into my office. She looked to be in her fifties, gray-haired, wearing a tight green summer shift that had once fit her better. She lowered her brow and eyed the surroundings, clearly uncomfortable.

I stood and offered her a seat. “If you’re not too busy, Deputy Kennerly, would you please join us?”

Johnny nodded. He was a big man, six-foot-six, dark-skinned with large brown eyes and a wide mouth—features he had inherited from his African American father. His Romanesque nose was a duplicate of his Italian mother’s. He wore a khaki Sheriff’s Department uniform with a handful of service badges pinned to his shirt. A .357 magnum was holstered on his hip.

“How may we help you, Ms. Gonzalez?” I sat down and smiled, encouraging her to speak.

She got right to it. “Have you ever heard of Barry Long, Junior?”

“Who hasn’t?”

“I work for him. I’m nanny to his son.”

“Okay.”

“There’s something wrong.”

“Meaning?”

“Mrs. Long has disappeared.” She looked quickly at both of us, trying to gauge our response. “Sometime last week.”

I glanced at Johnny who was seated beside Ms. Gonzalez. He had a quizzical look in his eye.

“Reverend Long,” she continued, “told me she had gone away for a while. He said I was to take full charge of the boy.”

“Did he mention where she had gone?”

“No.”

“What exactly did he say?”

“What he didn’t say was when she would come back.”

“How old is the boy?”

“Barely five. He’s very upset. Very unhappy. The Reverend is preparing for his annual revival Celebration and he moves back and forth between the house and his apartment at the Pavilion. Now he takes me and the boy with him. The boy cries and carries on a lot. He’s always screaming for his mother. When I try to talk about it with the Reverend, he tells me to handle it.”

“What is it you want from the Sheriff’s Department?”

“Reverend Long, he scares me.”

She cleared her throat and went on. “He and the men around him. They’re not good people. There’s something wrong there.”

“And you want us to look into it?”

“I want you to know what’s going on. What you do is up to you. I can’t be a part of it anymore. I’m leaving.”

“You mean you’re quitting?”

“I mean I’m leaving. I’m going somewhere to hide and pray they never find me.”

She stood and stared at me and at Johnny for several moments before picking up her purse and walking to the door.

Then she turned back to us.

“I think they killed her.”

Chapter Two

Freedom wasn’t the future I had in mind for myself. At age thirty, I had been faring quite well as a ranking LAPD homicide detective. I stand six-three in my bare feet, a former point guard, weighing in at one-seventy. I have blue eyes and dark blond hair, which I tend to haphazardly.

I worked out of the Hollywood division and lived within walking distance of the Cole Avenue Station. I was unmarried, with a promising career in law enforcement that impressed at least some of the women at my fitness club who believed, as did I, that hooking up was a satisfactory alternative to commitment. I was feeling as if I’d arrived, for whatever that was worth.

Then my father took ill. He hadn’t felt well during his re-election campaign and once he claimed victory, he paid a much-delayed visit to his GP.

He was quietly admitted to a private clinic where he underwent a battery of tests. One of the state’s leading neurologists consulted on the findings and confirmed the initial diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, otherwise known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

For the popular Sheriff of San Remo County—a coastal area located north of Santa Barbara—about to begin his third consecutive four-year term, this finding was nothing short of catastrophic.

He summoned the family. My sister flew in from Chicago. I drove up from L.A. Our stepmother, Regina Goodnow, herself the estimable mayor of Freedom Township, fluttered about the house doing all she could to ease the tension and make us comfortable.

My father, Burton Steel, Senior, was uncharacteristically subdued, his oversized personality deflated by the collapse of his heretofore robust health.

I’m Burton Steel, Junior. I hate the name Burton. I dislike the Junior part even more. Naming me after himself, in my estimation, was the ultimate in Burton Senior’s egocentricity, one of his innumerable character flaws. To differentiate us, I’m called Buddy.

My relationship with my father is complicated. I can’t say we’re friends. He’s autocratic to a fault and I could hardly wait to graduate from high school and get the hell out of his house.

I fled my life in Freedom and moved to New York where I studied criminal justice at John Jay College. I graduated near the top of my class, and when the offer to join the LAPD popped up, I grabbed it.

Now the family was gathered in the living room of the home I grew up in, an English-style manor house located in the hills above Highway 101.

When the old man broke the news, he spoke haltingly, already exhibiting the effects of the disease on his vocal cords, his voice rough as gravel, and suffering a loss of velocity.

“I’ve been given a death sentence. I’ve got fucking Lou Gehrig’s disease.”

My sister, Sandra, gasped.

“It’s in its early stages,” he went on. “But I’m a goner, sure as shit.”

Her Honor, my stepmother, chimed in. “Burton, please watch your language. You know how much I dislike all this swearing.”

“Shut up, Regina.”

“What can they do for it?” I pulled myself back from imagining the worst, hoping instead to hear some kind of optimistic prognosis.

“There’s no cure. They’ve put me on steroids. Prednisone. I can already feel the difference.”

“You mean you feel better?”

“I feel worse. Steroids slam the weight on you. It won’t be long before I look like fucking Oprah.”

“Burton, please,” Regina snapped.

Sandra leaned forward. “Is there anything we can do?”

My father shifted his eyes to fix his stare directly at me.

“I need you, Buddy. I’m likely to fade pretty fast. I want you here as my chief deputy. I’ll teach you the ropes. Train you to succeed me.”

“You’re kidding,” I said, but I knew better.