Excerpt

Excerpt

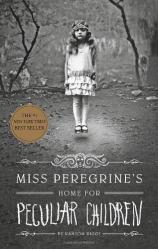

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

I picked up the flashlight and stepped toward the trees. My grandfather was out there somewhere, I was sure of it. But where? I was no tracker, and neither was Ricky. And yet something seemed to guide me anyway—a quickening in the chest; a whisper in the viscous air—and suddenly I couldn’t wait another second. I tromped into the underbrush like a bloodhound scenting an invisible trail.

It’s hard to run in a Florida woods, where every square foot not occupied by trees is bristling with thigh-high palmetto spears and nets of entangling skunk vine, but I did my best, calling my grandfather’s name and sweeping my flashlight everywhere. I caught a white glint out of the corner of my eye and made a beeline for it, but upon closer inspection it turned out to be just a bleached and deflated soccer ball I’d lost years before.

I was about to give up and go back for Ricky when I spied a narrow corridor of freshly stomped palmettos not far away. I stepped into it and shone my light around; the leaves were splattered with something dark. My throat went dry. Steeling myself, I began to follow the trail. The farther I went, the more my stomach knotted, as though my body knew what lay ahead and was trying to warn me. And then the trail of the flattened brush widened out, and I saw him.

My grandfather lay facedown in a bed of creeper, his legs sprawled out and one arm twisted beneath him as if he’d fallen from a great height. I thought surely he was dead. His undershirt was soaked with blood, his pants were torn, and one shoe was missing. For a long moment I just stared, the beam of my flashlight shivering across his body. When I could breathe again I said his name, but he didn’t move.

I sank to my knees and pressed the flat of my hand against his back. The blood that soaked through was still warm. I could feel him breathing ever so shallowly.

I slid my arms under him and rolled him onto his back. He was alive, though just barely, his eyes glassy, his face sunken and white. Then I saw the gashes across his midsection and nearly fainted. They were wide and deep and clotted with soil, and the ground where he’d lain was muddy from blood. I tried to pull the rags of his shirt over the wounds without looking at them.

I heard Ricky shout from the backyard. “I’M HERE!” I screamed, and maybe I should’ve said more, like danger or blood, but I couldn’t form the words. All I could think was that grandfathers were supposed to die in beds, in hushed places humming with machines, not in heaps on the sodden reeking ground with ants marching over them, a brass letter opener clutched in one trembling hand.

A letter opener. That was all he’d had to defend himself. I slid it from his finger and he grasped helplessly at the air, so I took his hand and held it. My nail-bitten fingers twinned with his, pale and webbed with purple veins.

“I have to move you,” I told him, sliding one arm under his back and another under his legs. I began to lift, but he moaned and went rigid, so I stopped. I couldn’t bear to hurt him. I couldn’t leave him either, and there was nothing to do but wait, so I gently brushed loose soil from his arms and face and thinning white hair. That’s when I noticed his lips moving.

His voice was barely audible, something less than a whisper. I leaned down and put my ear to his lips. He was mumbling, fading in and out of lucidity, shifting between English and Polish.

“I don’t understand,” I whispered. I repeated his name until his eyes seemed to focus on me, and then he drew a sharp breath and said, quietly but clearly, “Go to the island, Yakob. Here it’s not safe.”

It was the old paranoia. I squeezed his hand and assured him we were fine, he was going to be fine. That was twice in one day that I’d lied to him.

I asked him what happened, what animal had hurt him, but he wasn’t listening. “Go to the island,” he repeated. “You’ll be safe there. Promise me.”

“I will. I promise.” What else could I say?

“I thought I could protect you,” he said. “I should’ve told you a long time ago . . . ” I could see the life going out of him.

“Told me what?” I said, choking back tears.

“There’s no time,” he whispered. Then he raised his head off the ground, trembling with the effort, and breathed into my ear: “Find the bird. In the loop. On the other side of the old man’s grave. September third, 1940.” I nodded, but he could see that I didn’t understand. With his last bit of strength, he added, “Emerson—the letter. Tell them what happened, Yakob.”

With that he sank back, spent and fading. I told him I loved him. And then he seemed to disappear into himself, his gaze drifting past me to the sky, bristling now with stars.

A moment later Ricky crashed out of the underbrush. He saw the old man limp in my arms and fell back a step. “Oh man. Oh Jesus. Oh Jesus,” he said, rubbing his face with his hands, and as he babbled about finding a pulse and calling the cops and did you see anything in the woods, the strangest feeling came over me. I let go of my grandfather’s body and stood up, every nerve ending tingling with an instinct I didn’t know I had. There was something in the woods, all right—I could feel it.

There was no moon and no movement in the underbrush but our own, and yet somehow I knew just when to raise my flashlight and just where to aim it, and for an instant in that narrow cut of light I saw a face that seemed to have been transplanted directly from the nightmares of my childhood. It stared back with eyes that swam in dark liquid, furrowed trenches of carbon-black flesh loose on its hunched frame, its mouth hinged open grotesquely so that a mass of long eel-like tongues could wriggle out. I shouted something and then it twisted and was gone, shaking the brush and drawing Ricky’s attention. He raised his .22 and fired,pap-pap-pap-pap, saying, “What was that? What the hell was that?” But he hadn’t seen it and I couldn’t speak to tell him, frozen in place as I was, my dying flashlight flickering over the blank woods. And then I must’ve blacked out because he was saying Jacob, Jake, hey Ed areyouokayorwhat, and that’s the last thing I remember.

Excerpted from Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children by Ransom Riggs. Reprinted with permission by Quirk Books.

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

- Genres: Fiction, Photography

- paperback: 382 pages

- Publisher: Quirk Books

- ISBN-10: 1594746036

- ISBN-13: 9781594746031