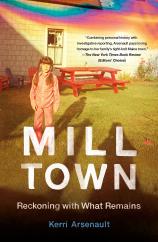

Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains

Review

Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains

In the past decade, a constant stream of reports highlighting the rampant pollution of the water and air of surrounding communities by factories and mills has dominated the news. Time after time, the story is eerily similar and now familiar: the company that provides employment to much of the town is gradually and knowingly poisoning many of its residents and destroying the environment around it. MILL TOWN is another recounting of this sad tale.

Kerri Arsenault grew up in Mexico, Maine, a small town on the Androscoggin River adjacent to the town of Rumford, home to a large paper mill that serves as the main employer for both towns. The largest smokestack for the mill overshadows the area “like a giant concrete finger,” its conveyor belts provide a constant background noise that the residents learn to tune out, the water has a metallic taste, and there is a lingering odor that pervades everything.

"Upon finishing MILL TOWN, readers will wonder how this same story can play out again and again and reach the depressing conclusion that, much like climate change, politicians are focused on the present and their reelection at the extreme neglect of the future."

When Arsenault graduated from high school, she went to college in Wisconsin and then moved numerous times trying out various jobs. Eventually she married a U.S. Coast Guard officer, and they continued to lead a mobile life until they settled down in the East. When she returned occasionally to Mexico, she began to see a town that was dying, in more ways than one. Speaking to a former resident, she learned that certain cancers and other diseases were present in Mexico and Rumford at a much higher rate, earning the area the nickname “Cancer Valley,” but few people were willing to challenge the company that provided a majority of the jobs to both towns.

MILL TOWN focuses on Mexico and its steady decline, but it also tracks the slow loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States and the erosion of the way that others view working-class people. She says that “people see the working-class as rednecks who like their guns and bad food, don’t care about the planet, are racist, or just plain dumb.” But the issues and identity are much more complicated than that, and the divide between the haves and have-nots continues to widen. As jobs disappear and people lose their livelihood, the ability to speak out against the destruction of the environment and the town grows that much harder for the working class.

Photographs are scattered throughout the book without descriptions. Sometimes the pictures are of people (presumably the individuals who are referenced on those particular pages), but other times there is just a random image whose details can be hard to discern. The lack of identifiers may be distracting to some.

Upon finishing MILL TOWN, readers will wonder how this same story can play out again and again and reach the depressing conclusion that, much like climate change, politicians are focused on the present and their reelection at the extreme neglect of the future. Corporations want to report profits at the expense of preserving the environment and protecting their employees. Arsenault ultimately argues that everyone is responsible. Until people stop turning a blind eye and instead speak up regarding the destruction of the environment and the poisoning of towns by the very entities that employ the residents of those towns, the country as a whole is doomed. How many times must this story be told before something is done?

Reviewed by Cindy Burnett on September 25, 2020

Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains

- Publication Date: September 7, 2021

- Genres: Memoir, Nonfiction

- Paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: St. Martin's Griffin

- ISBN-10: 1250799686

- ISBN-13: 9781250799685