Excerpt

Excerpt

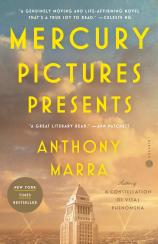

Mercury Pictures Presents

Sunny Siberia

1

When you entered the executive offices of Mercury Pictures International, you would first see a scale model of the studio itself. Artie Feldman, co-founder and head of production, installed it in the lobby to distract skittish investors from second thoughts. Complete with back lot, sound stages, and facilities buildings, the miniature was a faithful replica of the ten-acre studio in which it sat. Maria Lagana, as rendered by the miniaturist, was a tiny, featureless figure looking out Artie’s office window. And this was where the real Maria stood late one morning in 1941, hands holstered on her hips, watching a pigeon autograph the windshield of her boss’s new convertible. She’d like to buy that bird a drink.

“It’s a beautiful day out, Art,” Maria said. “You should really come have a look.”

“I have,” Artie said. “It made me want to jump.”

Artie wasn’t known for his joie de vivre, but he usually didn’t fantasize about ending it all this close to lunch. Maria wondered if the Senate Investigation into Motion Picture War Propaganda was giving him agita, but no—the crisis at hand was on his head. His bald spot had finally grown too large for his toupee to conceal.

Six other black toupees were shellacked atop wooden mannequin heads on the shelf behind his desk, where a more successful producer might display his Oscars. They were conversation starters. As in, Artie began conversations with new employees by telling them the toupees were the scalps of their predecessors.

As far as Maria could tell, the six hairpieces were the same indistinguishable model and style, but Artie had become convinced that each one crackled with the karmic energy of the hair’s original head, unrealized and awaiting release, like a static charge smuggled in a fingertip. Thus, he’d named his toupees after their personalities: The Heavyweight, The Casanova, The Optimist, The Edison, The Odysseus, and The Mephistopheles. Artie had never felt more at home in his adoptive country than when he learned the Founding Fathers had all worn toupees, even that showboat John Hancock. The only one who hadn’t was Benjamin Franklin. And look how he turned out: a syphilitic Francophile who got his jollies flying kites in the rain.

“Maybe the toupee shrunk,” he said, still hoping for a miracle.

“I think you’ll need one with more coverage, Art.”

“That’s the second time this year. Christ, when will it end?”

“Life’s nasty and brutish but at least it’s short.”

“Yeah? I’m not so optimistic.”

Artie didn’t believe in aging gracefully. He didn’t believe in aging at all. At fifty-three, he maintained the same exercise regime that had made him a promising semi-professional boxer before a shattered wrist forced him into the only other business to reward his brand of controlled aggression. (He still kept a speedbag mounted to his office wall and liked to pummel it while in meetings with unaccommodating agents.) Sure, maybe he lost a step; maybe his knees sounded like a pair of maracas when he climbed stairs; maybe the boys in the mailroom let him win when he challenged them to arm-wrestling matches—but he wasn’t getting old.

Or so Maria imagined Artie telling himself. In truth, she’d begun to worry about him. In four days, he would sit at a witness table on Capitol Hill, where he would testify alongside the heads of Warner Bros, MGM, Twentieth Century–Fox, and Paramount. It was shaping into a pivotal confrontation between campaigners for free speech and crusaders for government censorship. But as far as Maria could tell, Artie was more preoccupied with his toupee than his opening statement.

On the topic of censorship, he said, “Have you heard back from Joe Breen?”

“Earlier this morning.”

“And? Will he approve the script for Devil’s Bargain?”

Maria said nothing.

“I’m going to pull the rest of my hair out, aren’t I?”

“I’m afraid so,” she admitted.

Maria had started working at Mercury a decade earlier, rising from the typing pool to the front office. At the age of twenty-eight, she was an associate producer and Artie’s deputy, a job that demanded the talents of a general, diplomat, hostage negotiator, and hairdresser. Among her duties was getting every Mercury picture blessed by the puritans and spoilsports who upheld the moral standards of movies at the Production Code Administration. The grand inquisitor over there was Joseph Breen, a bluenose so distraughtfully Catholic he’d once bowdlerized a Jesus biopic for sticking too close to the source material; apparently, a foreign-born Jew advocating redistribution smacked of Bolshevism to Breen. Committed to making pictures gratuitously inoffensive, Breen withheld Production Code approval from any movie dealing with contentious subjects. Throughout the 1930s, if you only got your news from the local picture house, you’d find the American South untroubled by Jim Crow and Europe untouched by fascism. But by late summer 1941, not even a force of blandness as entrenched as the Production Code could keep the European crisis from the screen.

In response to pro-interventionist messages in recent movies, a group of isolationist senators accused Hollywood of plotting with Roosevelt “to make America punch drunk with propaganda to push her into war” against Germany and Italy. Congressional hearings were hastily arranged to investigate these charges and propose legislative remedies. And Artie Feldman, ever reliant on the free publicity of controversy to find an audience, wanted to both undermine the legitimacy of the investigation and capitalize on his newfound notoriety with Mercury’s next movie.

Maria passed Artie the script she’d received back from the Production Code Administration that morning. Joe Breen had rerouted scenes with the frantic arrows of a besieged field commander. Devil’s Bargain was a clever idea—no matter her misgivings, Maria would admit that much. Written by a German émigré, it retold the Faustian legend through the story of a Berlin filmmaker who agrees to direct indoctrination movies in exchange for the funding to finish his long-gestating magnum opus. In a pivotal sequence, a visiting delegation of American congressmen watches one of these propaganda films and leaves the theater persuaded the real enemy to peace is not in Berlin but in Hollywood. Of course, insinuating that US senators were easily duped conspiracists ensured the script would never receive Production Code approval. Maria supposed she should feel disappointed, yet for reasons she would not admit to Artie, she was relieved Joseph Breen had sentenced Devil’s Bargain to death by a thousand cuts.

“I’m surprised he didn’t censor the spaces between the words,” Artie said, flipping through the blue-penciled script. Maria’s marginalia were heavily seasoned with profanity and exclamation points. “Breen’s always had it in for me. I’ve never understood it.”

“You did call him a ‘great sanctimonious windbag’ in the New York Daily News.”

“I was misquoted. I never called him ‘great.’ ” Artie tossed the script on his desk and peeled off his hairpiece. His liver-spotted scalp resembled a slab of pimento loaf. Maria always found the sight of it oddly moving, a sign of the trust established over the ten years they had worked together. Artie allowed no one else at Mercury to see him in between toupees. He turned to her and said, “What do you think—any chance we can salvage this?”

Artie assumed Maria’s background made her a natural fit for supervising the production of Devil’s Bargain. Long before she became his second-in-command, Maria and her mother had fled Italy as political exiles after Mussolini had her father, one of Rome’s most prominent lawyers, sentenced to internal exile in the Calabrian hinterlands. Over the years their correspondence had imbued Maria with a contempt for censors and a talent for circumventing them.

Sometimes she felt life had professionalized her to hide in plain sight. Fascism and Catholicism had educated her in navigating repressive ideologies, and growing up a girl in an Italian family meant you were, existentially, suggested rather than shown. Gesture and insinuation comprised the Italian American vernacular, from mamma to Mafia, and coming from a diaspora where desires and death threats went articulately unspoken, Maria had a knack for smuggling subtext past the border guards of decorum at the Production Code Administration. Nevertheless, in the case of Devil’s Bargain, she agreed with the censors’ decision. Meddling in politics was for the rich, the powerful, or the self-destructive; she learned this from her father’s example and had no wish to become him.

“I think this one is well and truly Breened,” she said.

Mercury Pictures Presents

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 448 pages

- Publisher: Hogarth

- ISBN-10: 0451495217

- ISBN-13: 9780451495211