Excerpt

Excerpt

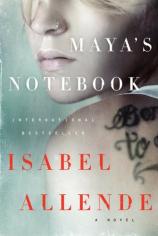

Maya's Notebook

SUMMER

January, February, March

A week ago my grandmother gave me a dry-eyed hug at the San Francisco airport and told me again that if I valued my life at all, I should not get in touch with anyone I knew until we could be sure my enemies were no longer looking for me. My Nini is paranoid, as the residents of the People’s Independent Republic of Berkeley tend to be, persecuted as they are by the government and extraterrestrials, but in my case she wasn’t exaggerating: no amount of precaution could ever be enough. She handed me a hundred-page notebook so I could keep a diary, as I did from the age of eight until I was fifteen, when my life went off the rails. “You’re going to have time to get bored, Maya. Take advantage of it to write down the monumental stupidities you’ve committed, see if you can come to grips with them,” she said. Several of my diaries are still in existence, sealed with industrial-strength adhesive tape. My grandfather kept them under lock and key in his desk for years and now my Nini has them in a shoebox under her bed. This will be notebook number nine. My Nini believes they’ll be of use to me when I get psychoanalyzed, because they contain the keys to untie the knots of my personality; but if she’d read them, she’d know they contain a huge pile of tales tall enough to outfox Freud himself. My grandmother distrusts professionals who charge by the hour on principle, since quick results are not profitable for them. However, she makes an exception for psychiatrists, because one of them saved her from depression and from the traps of magic when she took it into her head to communicate with the dead.

I put the notebook in my backpack, so I wouldn’t upset her, with no intention of using it, but it’s true that time stretches out here and writing is one way of filling up the hours. This first week of exile has been a long one for me. I’m on a tiny island so small it’s almost invisible on the map, in the middle of the Dark Ages. It’s complicated to write about my life, because I don’t know how much I actually remember and how much is a product of my imagination; the bare truth can be tedious and so, without even noticing, I change or exaggerate it, but I intend to correct this defect and lie as little as possible in the future. And that’s why now, when even the Yanomamis of the Amazonas use computers, I am writing by hand. It takes me ages and my writing must be in Cyrillic script, because I can’t even decipher it myself, but I imagine it’ll gradually straighten out page by page. Writing is like riding a bicycle: you don’t forget how, even if you go for years without doing it. I’m trying to go in chronological order, since some sort of order is required and I thought that would make it easy, but I lose my thread, I go off on tangents or I remember something important several pages later and there’s no way to fit it in. My memory goes in circles, spirals, and somersaults.

My name is Maya Vidal. I’m nineteen years old, female, single – due to a lack of opportunities rather than by choice, I’m currently without a boyfriend. Born in Berkeley, California, I’m a U.S. citizen, and temporarily taking refuge on an island at the bottom of the world. They named me Maya because my Nini has a soft spot for India and my parents hadn’t come up with any other name, even though they’d had nine months to think about it. In Hindi, maya means “charm, illusion, dream”: nothing at all to do with my personality. Attila would suit me better, because wherever I step no pasture will ever grow again. My story begins in Chile with my grandmother, my Nini, a long time before I was born, because if she hadn’t emigrated, she’d never have fallen in love with my Popo or moved to California, my father would never have met my mother and I wouldn’t be me, but rather a very different Chilean girl. What do I look like? I’m five-ten, a hundred and twenty-eight pounds when I play soccer and several more if I don’t watch out. I’ve got muscular legs, clumsy hands, blue or gray eyes, depending on the time of day, and blond hair, I think, but I’m not sure since I haven’t seen my natural hair color for quite a few years now. I didn’t inherit my grandmother’s exotic appearance, with her olive skin and those dark circles under her eyes that make her look a little depraved, or my father’s, handsome as a bullfighter and just as vain. I don’t look like my grandfather either — my magnificent Popo — because unfortunately he’s not related to me biologically, since he’s my Nini’s second husband.

I look like my mother, at least as far as size and coloring go. She wasn’t a princess of Lapland, as I used to think before I reached the age of reason, but a Danish airhostess my father, who’s a pilot, fell in love with in mid-air. He was too young to get married, but he got it into his head that this was the woman of his dreams and stubbornly pursued her until she eventually got tired of turning him down. Or maybe it was because she was pregnant. The fact is they got married and regretted it within a week, but they stayed together until I was born. Days after my birth, while her husband was flying somewhere, my mother packed her bags, wrapped me up in a little blanket and took a taxi to her in-laws’ house. My Nini was in San Francisco protesting against the Gulf war, but my Popo was home and took the bundle she handed him, without much of an explanation, before running back to the taxi that was waiting for her. His granddaughter was so light he could hold her in one hand. A little while later the Danish woman sent divorce papers by mail and as a bonus a document renouncing custody of her daughter. My mother’s name is Marta Otter and I met her the summer I was eight, when my grandparents took me to Denmark.

I’m in Chile, country of my grandmother Nidia Vidal, where the ocean takes bites off the land and the continent of South America strings out into islands. To be more specific, I’m in Chiloé, part of the Lakes Region, between the 41st and 43rd southern parallel, an archipelago of more or less nine thousand square kilometers and two hundred thousand or so inhabitants, all of them shorter than me. In Mapudungun, the language of the region’s indigenous people, Chiloé means land of cáhuiles, which are these screechy, black-headed seagulls, but it should be called land of wood and potatoes. Aside from the Isla Grande, where the most populous cities are, there are lots of little islands, some of them uninhabited. Some of the islands are in groups of three or four and so close to each other, that at low tide you can walk from one to the next, but I didn’t have the good luck to end up on one of those: I live forty-five minutes, by motorboat when the sea is calm, from the nearest town.

My trip from northern California to Chiloé began in my grandmother’s venerable yellow Volkswagen, which has suffered seventeen crashes since 1999, but runs like a Ferrari. I left in the middle of winter, one of those days of wind and rain when San Francisco bay loses its colors and the landscape looks like it was drawn with white, black, and grey brush strokes. My grandmother was driving the way she usually does, clutching the steering wheel like a life preserver, the car making death rattles, her eyes fixed on me more than on the road, busy giving me my final instructions. She still hadn’t explained where exactly it was she was sending me; Chile, was all she’d said while concocting her plan to make me disappear. In the car she revealed the details and handed me a cheap little guidebook.

“Chiloé? What is this place?” I asked.

“You’ve got all the necessary information right there,” she said, pointing to the book.

“It seems really far away…”

“The further the better. I have a friend in Chiloé, Manuel Arias, the only person in this world, apart from Mike O’Kelly, I’d dare ask to hide you for a year or two.

“A year or two! You’re demented, Nini!”

“Look, kiddo, there are moments when a person has no control over their own life, things happen that’s all. This is one of those moments,” she announced with her nose pressed against the windshield, trying to find her way, while we took stabs in the dark in the tangle of highways.

We were late arriving at the airport and separated without any sentimental fuss; the last image I have of her is of the Volkswagen sneezing in the rain as she drove away.

I flew to Dallas, which took several hours, squeezed between the window and a fat woman who smelled of roast peanuts, and then ten hours in another plane to Santiago, awake and hungry, remembering, thinking and reading the book on Chiloé, which exalted the virtues of the landscape, the wooden churches and rural living. I was terrified. Dawn broke on January 2nd of this year, 2009, with an orange sky over the purple Andes, definitive, eternal, immense, when the pilot’s voice announced our descent. Soon a green valley appeared, rows of trees, pastures, crops, and in the distance Santiago, where my grandmother and my father were born and where there is a mysterious piece of my family history.

I know very little about my grandmother’s past, which she has rarely mentioned, as if her life had really begun when she met my Popo. In 1974, in Chile, her first husband, Felipe Vidal, died a few months after the military coup that overthrew Salvador Allende’s socialist government and installed a dictatorship in the country. Finding herself a widow, she decided that she didn’t want to live under an oppressive regime and emigrated to Canada with her son Andrés, my dad. He hasn’t added much to the tale, because he doesn’t remember very much about his childhood, but he still reveres his father, of whom there are only three photographs in existence. “We’re never going back, are we?” Andrés said in the plane that took them to Canada. It wasn’t a question, it was an accusation. He was nine years old, had grown up all of a sudden over the last months, and wanted explanations, because he realized his mother was trying to protect him with half-truths and lies. He’d bravely accepted the news of his father’s unexpected heart attack and the news that he’d been buried before he could see the body and say goodbye. A short time later he found himself on a plane to Canada. “Of course we’ll come back, Andrés,” his mother assured him, but he didn’t believe her.

In Toronto they were taken in by Refugee Committee volunteers, who gave them suitable clothing and set them up in a furnished apartment, with the beds made and the fridge full. The first three days, while the provisions lasted, mother and son remained shut up indoors, trembling with solitude, but on the fourth they had a visit from a social worker who spoke good Spanish and informed them of the benefits and rights due to all Canadian residents. First of all they received intensive English classes and the boy was enrolled at school; then Nidia got a job as a driver to avoid the humiliation of receiving handouts from the State without working. It was the least appropriate job for my Nini, who is a rotten driver today, and back then was even worse.

The brief Canadian fall gave way to a polar winter, wonderful for Andrés, now called Andy, who discovered the delights of ice-skating and skiing, but unbearable for Nidia, who could never get warm or get over the sadness of having lost her husband and her country. Her mood didn’t improve with the coming of a faltering spring or with the flowers, which sprouted overnight like a mirage where before there had been hard-packed snow. She felt rootless and kept her bags packed, waiting for the chance to return to Chile as soon as the dictatorship fell, never imagining it was going to last for sixteen years.

Nidia Vidal stayed in Toronto for a couple of years, counting the days and the hours, until she met Paul Ditson II, my Popo, a professor at the University of California in Berkeley, who had gone to Toronto to give a series of lectures about an elusive planet, whose existence he was trying to prove by way of poetic calculations and leaps of the imagination. My Popo was one of the few Afro-American astronomers in an overwhelmingly white profession, an eminence in his field and the author of several books. As a young man he’d spent a year at Lake Turkana, in Kenya, studying the ancient megaliths of the region. He developed a theory, based on archeological discoveries, that those basalt columns were astronomical observatories and had been used three hundred years before the Christian era to determine the Borana lunar calendar, which is still in use among shepherds in Ethiopia and Kenya. In Africa he learned to observe the sky without prejudice and that’s how he began to suspect the existence of the invisible planet, for which he later searched the sky in vain with the most powerful telescopes.

The University of Toronto put him up in a suite for visiting academics and hired a car for him through an agency, which is how Nidia Vidal ended up escorting him during his stay. When he found out that his driver was Chilean, he told her he’d been at La Silla observatory, in Chile. He said that in the southern hemisphere you can see constellations unknown in the north, like the galaxies the Small Magellanic Cloud and the Large Magellanic Cloud. In some parts of the country, he told her, the nights are so clear and the climate so dry, providing ideal conditions for scrutinizing the firmament. That’s how they discovered that galaxies cluster together in designs that resemble spiderwebs.

By one of those coincidences that normally happen only in novels, his visit to Chile ended on the very same day in 1974 that she left with her son for Canada. I often wonder if maybe they were in the airport at the same time waiting for their respective flights, but not meeting. According to them this would have been impossible, because he would have noticed such a beautiful woman and she would have seen him too, because a black man stood out in Chile back then, especially one as tall and handsome as my Popo.

A single morning driving her passenger around Toronto was enough for Nidia to realize that he possessed that rare combination of a brilliant mind with the imagination of a dreamer, but entirely lacked any common sense, something she was proud to have in abundance herself. My Nini could never explain to me how she’d reached that conclusion from behind the steering wheel of a car while navigating her way through the traffic, but the fact is she was absolutely right. The astronomer was living a life as lost as the planet he was searching the sky for; he could calculate in less than the blink of an eye how long it would take a space ship to arrive at the moon if it was traveling at 28,286 kilometers per hour, but he remained perplexed by an electric coffee-maker. She had not felt the elusive flutter of love for years and this man, very different to all those she’d met in her thirty-three years, intrigued and attracted her.

My Popo, quite frightened by his driver’s boldness with the traffic, also felt curiosity about the woman hidden inside a uniform that was too big for her and a bear hunter’s cap. He was not a man to give in easily to sentimental impulses and if the idea of seducing her might have briefly crossed his mind, he immediately dismissed it as awkward. My Nini on the other hand, who had nothing to lose, decided to collar the astronomer before he finished his lectures. She liked his mahogany color — she wanted to see all of him — and sensed that the two of them had a lot in common: he had astronomy and she astrology, which she considered to be practically the same thing. She thought they’d both come from a long way away to meet at this spot on earth and in their destinies, because it was written in the stars. My Nini lived according to her horoscope back then, but she didn’t leave everything up to fate. Before taking the initiative of a surprise attack she made sure he was single, in a good financial situation, healthy and only eleven years older than her, although at first glance she might have looked like his daughter if they’d been the same race. Years later my Popo would laugh and tell people that if she hadn’t knocked him out in the first round, he’d still be wandering around in love with the stars.

The second day the professor sat in the front seat to get a better look at his driver and she took several unnecessary trips around the city to give him time to do so. That very night, after giving her son his dinner and putting him to bed, Nidia took off her uniform, took a shower, put on some lipstick and presented herself before her prey with the pretext of returning a folder he’d left in the car and which she could just as easily have given him the following morning. She had never taken such a daring romantic decision. She arrived at the building despite an icy blizzard, went up to the suite, crossed herself for encouragement and knocked on the door. It was eleven thirty when she smuggled herself definitively into the life of Paul Ditson II.

My Nini had lived like a recluse in Toronto. At night she missed the weight of a masculine hand on her waist, but she had to survive and raise her son in a country where she’d always be a foreigner; there was no time for romantic dreams. The courage she’d armed herself with that night in order to get to the astronomer’s door vanished as soon as he opened it looking sleepy and wearing pajamas. They looked at each other for half a minute, without knowing what to say, because he wasn’t expecting her and she hadn’t made a plan, until he invited her in. He was surprised at how different she looked without the hat of her uniform, admired her dark hair, her face with its uneven features and her slightly crooked smile, which before he’d only been able to glimpse on the sly. She was surprised by the difference in size between the two of them, less noticeable inside the car: on tiptoes her nose reached the middle of the giant’s chest. She immediately noticed the cataclysmic state of the tiny suite and concluded that the man seriously needed her.

Paul Ditson II had spent most of his life studying the mysterious behavior of celestial bodies, but he knew very little about female ones and nothing of the vagaries of love. He’d never fallen in love and his most recent relationship had been with a colleague in his faculty with whom he got together twice a month, an attractive Jewish woman in good shape for her age, who always insisted on paying half the bill in restaurants. My Nini had only loved two men, her husband and a lover she’d torn out of her head and heart ten years before. Her husband was a scatterbrained companion, absorbed in his work and political activities, who traveled non-stop and was always too distracted to pay any attention to her needs, and the other was a relationship that had been cut short. Nidia Vidal and Paul Ditson II were both ready for the love that would unite them to the end.

I heard my grandparents’ possibly-fictionalized love story many times, and ended up memorizing it word for word, like a poem. I don’t know, of course, the details of what happened that night behind closed doors, but I can imagine them based on what I know about both of them. Did my Popo suspect, when he opened the door to this tiny Chilean woman, that he was at a crucial juncture and that the road he chose would determine his future? No, I’m sure, such tackiness would never have crossed his mind. And my Nini? I see her advancing like a somnambulist through the clothes thrown on the floor and the overflowing ashtrays, crossing the little living room, walking into the bedroom and sitting down on the bed, because the armchair and all the other chairs were covered in papers and books. He knelt down beside her to embrace her and they stayed like that for a long time, trying to accommodate themselves to this sudden intimacy. Maybe she began to feel stifled by the heating and he helped her to get out of her coat and boots; then they caressed each other hesitantly, recognizing each other, delving into their souls to make sure they weren’t mistaken. “You smell of tobacco and dessert. And you’re smooth and black like a seal,” my Nini told him. I heard that phrase many times.

The last part of the legend I don’t have to invent, because they told me. With that first embrace, my Nini concluded that she’d known the astronomer in other lives and other times, that this was just a re-encounter and that their astral signs and tarot cards were aligned. “Thank goodness you’re a man, Paul. Imagine if in this reincarnation you’d come back as my mother…” she sighed, sitting on his lap. “Since I’m not your mother, why don’t we get married?” he answered.

Two weeks later she arrived in California dragging her son, who had no desire to emigrate for a second time, with a three-month engagement visa, at the end of which she had to either get married or leave the country. They got married.

I spent my first day in Chile wandering around Santiago with a map, in a heavy, dry heat, killing time until my bus left for the south. It’s a modern city, with nothing exotic or picturesque, there are no Indians in traditional clothes or colonial neighborhoods with bold colored houses, like I’d seen with my grandparents in Guatemala or Mexico. I went up in a funicular to the top of a hill, an obligatory trip for tourists, and got an idea of the size of the capital, which looks like it goes on forever, and of the pollution that covers it like a dusty mist. At dusk I boarded an apricot-colored bus heading south, to Chiloé.

I tried and tried to sleep, rocked by the movement, the purring of the motor and the snores of the other passengers, but it’s never been easy for me to sleep and much less now, when I still have residues of the wild life running through my veins. When the sun came up we stopped to use the restroom and have a coffee at a posada, in the middle of a pastoral landscape of rolling green hills and cows, and then we went on for another several hours until we reached a rudimentary port, where we could stretch our legs and buy cheese and seafood empanadas from some women wearing white coats like nurses. The bus boarded a ferry to cross the Chacao Strait: half an hour sailing silently over a luminous sea. I got off the bus to look over the edge with all the rest of the numb passengers who, like me, had spent many hours imprisoned in their seats. Defying the biting wind, we admired the flocks of swallows, like kerchiefs in the sky, and the toninas, dolphins with white bellies that danced alongside the ferry.

The bus left me in Ancud, on the Isla Grande the second largest city of the archipelago. From there I had to take another bus to the town where Manuel Arias was expecting me, but I discovered that my wallet was missing. My Nini had warned me about Chilean pickpockets and their magician’s skill: they’ll very kindly steal your soul. Luckily they left my photo of my Popo and my passport, which I had in the other pocket of my backpack. I was alone, without a single cent, in an unknown country, but if I’d learned anything from my ill-fated adventures of last year it was not to get overwhelmed by minor inconveniences.

In one of the little souvenir shops in the plaza, where they sold Chiloé knits, there were three women sitting in a circle, chatting and knitting, and I assumed that if they were like my Nini, they’d help me; Chilean women fly to the rescue of anyone in distress, especially an outsider. I explained the problem in my hesitant Spanish and they immediately dropped their knitting needles and offered me a chair and an orange soda, while they discussed my case talking over each other in their rush to give opinions. They made several calls on a cell phone and got me a lift with a cousin who was going my way; he could take me in a couple of hours and didn’t mind making a short detour to drop me off at my destination.

I took advantage of the wait to have a look around town and visit a museum of the churches of Chiloé, designed by Jesuit missionaries three hundred years earlier and raised plank by plank by the Chilotes, who are masters boat builders and can make anything out of wood. The structures are sustained by an ingenious assembly system without using a single nail, and the vaulted ceilings are upside-down boats. As I came out of the museum I met a dog. He was medium sized, lame, with stiff gray fur and a lamentable tail, but with the dignified demeanor of a pedigree animal. I offered him the empanada I had in my backpack, and he took it gently in his big yellow teeth, put it down on the ground and looked at me, telling me clearly that his hunger was not for food, but for company. My step-mother, Susan, was a dog-trainer and had taught me never to touch any animal before they approach, which they’ll do when they feel safe, but with this one we skipped the protocol and from the start we got along well. We did a little sightseeing together and at the agreed time I went back to where the women were knitting. The dog stayed outside the shop, politely, with just one paw on the threshold.

The cousin showed up an hour later than he said he would in a van crammed to the roof with stuff, accompanied by his wife with a baby at her breast. I thanked my benefactors, who had also lent me the cell phone to get in touch with Manuel Arias, and said goodbye to the dog, but he had other plans: he sat at my feet and swept the ground with his tail, smiling like a hyena; he had done me the favor of honoring me with his attention and now I was his lucky human. I changed tactics. “Shoo! Shoo! Fucking dog,” I shouted at him in English. He didn’t move, while the cousin observed the scene with pity. “Don’t worry, señorita, we can bring your Fahkeen,” he said at last. And in this way that ashen creature acquired his new name; maybe in his previous life he’d been called Prince. We could barely squeeze into the jam-packed vehicle and an hour later we arrived in the town where I was supposed to meet my grandmother’s friend, who’d said to wait in front of the church, facing the sea.

The town, founded by the Spanish in 1567, is the oldest in the archipelago and has a population of two thousand, but I don’t know where they all were, because I saw more hens and sheep than humans. I waited for Manuel for a long time sitting on the steps of a blue and white painted church with Fahkeen and observed from a certain distance by four silent and serious little kids. All I knew about him was that he was a friend of my grandmother’s and they hadn’t seen each other since the 1970s, but they’d kept in touch sporadically, first by letter, as they did in prehistoric times, and then by email.

Manuel Arias finally appeared and recognized me from the description my Nini had given him over the phone. What would she have told him? That I’m an obelisk with hair dyed four primary colors and a nose ring. He held out his hand and looked me over quickly, evaluating the remains of blue nail polish on my bitten fingernails, frayed jeans and commando boots spray-painted pink, that I got at a Salvation Army store when I was on the streets.

“I’m Manuel Arias,” the man introduced himself, in English.

“Hi. I’m on the run from the FBI, Interpol and a Las Vegas criminal gang,” I announced bluntly, to avoid any misunderstandings.

“Congratulations,” he said.

“I haven’t killed anybody and, frankly, I don’t think any of them would go to the trouble of coming to look for me all the way down here in the asshole of the world.”

“Thanks.”

“Sorry, I didn’t mean to insult your country, man. Actually it’s really pretty, lots of green and lots of water, but look how far away it is!”

“From what?”

“From California, from civilization, from the rest of the world. My Nini didn’t tell me it’d be cold.”

“It’s summer,” he informed me.

“Summer in January! Who’s ever heard of that!”

“Everyone in the southern hemisphere,” he replied dryly.

Bad news, I thought, no sense of humor. He invited me to have a cup of tea, while we waited for a truck that was bringing him a refrigerator and should have been there three hours ago. We went into a house marked with a white cloth flying from a pole, like a flag of surrender, a sign that they sell fresh bread there. There were four rustic tables with oilskin tablecloths and unmatched chairs, a counter and a stove, where a soot-blackened kettle was boiling away. A heavy-set woman, with a contagious laugh, greeted Manuel Arias with a kiss on the cheek and looked at me a little warily before deciding to kiss me too.

“Americana?” she asked Manuel.

“Isn’t it obvious?” he said.

“But what happened to her head?” she added, pointing to my dyed hair.

“I was born this way,” I told her cheekily in Spanish.

“The gringuita speaks Christian!” she exclaimed with delight. “Sit, sit down, I’ll bring you a little tea right away.”

She took me by the arm and sat me down resolutely in one of the chairs, while Manuel explained that in Chile a gringo is any blond English-speaking person and when the diminutive is used, as in gringuito or gringuita, it’s a term of affection.

The innkeeper brought us tea, a fragrant pyramid of bread just out of the oven, butter and honey, and then she sat down with us to make sure we’d eat as much as we should. Soon we heard the sneezing of a truck, which bounced along the unpaved, pot-holed street, with a refrigerator balanced in the back. The woman leaned out the door, whistled and a moment later there were several young men helping to get the appliance off the back of the truck, carry it down to the beach and load it onto Manuel’s motorboat using a gangway of planks.

The vessel was about eight meters long, fiberglass, painted white, blue and red, the colors of the Chilean flag, almost the same as that of Texas, that flew from the prow. The name was painted along one side: Cahuilla. They tied the refrigerator as well as possible while keeping it upright and helped me in. The dog followed me with his pathetic little trot; one of his paws was a bit shriveled and he walked leaning to one side.

“And this guy?” Manuel asked me.

“He’s not mine, he latched onto me in Ancud. I’ve been told that Chilean dogs are very intelligent and this one’s a good breed.”

“He must be a cross between a German shepherd and a fox terrier. He’s got the body of a big dog with a little dog’s short legs,” was Manuel’s opinion.

“After I give him a bath, you’ll see how fine he is.”

“What’s his name?” he asked.

“Fucking dog in Chilean.

“What?

“Fahkeen.

“I hope your Fahkeen gets along with my cats. You’ll have to tie him up at night so he won’t go out and kill sheep,” he warned me.

“That won’t be necessary, he’s going to sleep with me.”

Fahkeen squashed himself to the bottom of the boat, with his nose in between his front paws, and stayed absolutely still there, without taking his eyes off me. He’s not affectionate, but we understand each other in the language of flora and fauna: telepathic Esperanto.

From the horizon an avalanche of big clouds rolled towards us and an icy wind was blowing but the sea was calm. Manuel lent me a woolen poncho and didn’t say anything more, concentrating on steering and the instruments, compass, GPS, marine wave radio and who knows what else, while I studied him out of the corner of my eye. My Nini had told me that he was a sociologist, or something like that, but in his little boat he could pass for a sailor: medium height, thin, strong, fiber and muscle, cured by the salty wind, with wrinkles of stern character, short thick hair, eyes as grey as his hair. I don’t know how to calculate the age of old people; this one looks ok from a distance, because he walks fast and he hasn’t got that hump old men get, but up close you can tell he’s older than my Nini, so he must be seventy-something. I’ve fallen into his life like a bombshell. I’ll have to be stepping on eggshells, so he won’t regret having given me shelter.

After almost an hour on the water, passing quite a few islands that appeared uninhabited, even though they weren’t, Manuel Arias pointed to a headland that from the distance was barely a dark brush stroke but up close turned out to be a hill with a beach of blackish sand and rocks at the edge of it, where four wooden boats were drying upside down. He docked the Cahuilla at a floating wharf and threw a couple of thick ropes to a bunch of kids, who’d come running down and they tied the boat to some posts quite capably. “Welcome to our metropolis,” said Manuel, pointing to a village of wooden houses on stilts in front of the beach. A shiver ran up my spine, because from here on in this would be my whole world.

A group came down to the beach to inspect me. Manuel had told them an American girl was coming to help him with his research; if these people were expecting someone respectable, they were in for a disappointment, because the Obama T-shirt I was wearing, a Christmas present from my Nini, wasn’t long enough to cover my belly-button.

Unloading the refrigerator without tilting it was a job for several volunteers, who encouraged and hurried each other with loud laughter, as it was starting to get dark. We walked up to town in a procession, the refrigerator in the lead, then Manuel and I, behind us a dozen shouting little kids and bringing up the rear a ragtag bunch of dogs furiously barking at Fahkeen, but without getting too close, because his attitude of supreme disdain clearly indicated that the first to do so would suffer the consequences. Fahkeen seems difficult to intimidate and won’t let any of them smell his butt. We walked past a cemetery, where a few goats with swollen udders were grazing among the plastic flowers and what looked like dollhouses marking the graves, some with furniture for the use of the dead.

In the village, the stilt houses were connected by wooden bridges and in the main street, to give it a name, I saw donkeys, bicycles, a jeep with the crossed rifles emblem of the carabineros, the Chilean police, and three or four old cars, which in California would be collectors’ items if they were less banged up. Manuel explained that due to the uneven terrain and inevitable mud in the winter, all heavy transport is done by oxen cart, the lighter stuff by mules, and people got around on horseback and on foot. A few faded signs identified some humble shops, a couple of grocery stores, a pharmacy, several bars, two restaurants, which consisted of a couple of metal tables in front of a couple of fish shops, and one internet café, where they sold batteries, soda pop, magazines and knickknacks for visitors, who arrive once a week, carted in by ecotourism agencies, to enjoy the best curanto in Chiloé. I’ll describe curanto later on, because I haven’t tried it yet.

Some people came out to take a cautious look at me, in silence, until a short, stocky man decided to say hello. He wiped his hand on his pants before offering it to me, smiling with teeth edged in gold. This was Aurelio Ñancupel, descendent of a famous pirate and the most necessary person on the island, because he sells alcohol on credit, extracts molars and has a flat-screen TV, which his customers enjoy when there’s electricity. His place has a very appropriate name: The Tavern of the Dead; because of its advantageous location near the cemetery, it’s the obligatory stopping point for mourners to alleviate the sorrow of every funeral.

Ñancupel became a Mormon with the idea of being able to have several wives and discovered too late that they’d renounced polygamy after a new prophetic revelation, more in line with the U.S. Constitution. That’s how Manuel Arias described him to me, while the man himself doubled over with laughter, echoed by the crowd. Manuel also introduced me to other people, whose names I couldn’t remember, who seemed too old to be the parents of that gang of children; now I know they’re the grandparents, because the generation in between all work far from the island.

So then this fiftyish woman with a commanding air came walking up the street. She looked tough and attractive with hair that beige color blonde turns when it goes gray, done up in a messy bun at the nape of her neck. This was Blanca Schnake, principal of the school, who people call, out of respect, Auntie Blanca. She kissed Manuel on the cheek, the way they do here, and gave me an official welcome in the name of the community; this dissolved the tension in the atmosphere and tightened the circle of nosy bystanders around me. Auntie Blanca invited me to visit the school the next day and offered me free use of the library, two computers and videogames, which I can use till March, when the kids go back to class; after that the timetable will be more limited. She added that on Saturday they showed the same movies at the school that were playing in Santiago, but for free. She bombarded me with questions and I summed up, in my beginner’s Spanish, my two-day trip from California and the theft of my wallet, which provoked a chorus of laughter from the kids, who were quickly silenced by a glacial look from Auntie Blanca. “Tomorrow I’m going to make you some machas a la parmesana, so the gringuita can start getting to know some Chiloé cuisine. I’ll expect you around nine,” she told Manuel. Afterward I found out that machas are a special kind of razor clam found only in the southern Pacific and that the correct thing to do is to arrive an hour after the time you’re told. They have dinner very late here.

When we finished our brief tour around the town, we climbed into a cart pulled by two mules. The refrigerator was secured behind us, and off we went, very slowly, along a barely visible track through the pasture, followed by Fahkeen.

Manuel Arias lives a mile — or a kilometer and a half, as they say here — from town, right on the sea, but there’s no access to the property by boat because of the rocks. His house is a good example of the region’s architecture, he told me with a note of pride in his voice. To me it looks like all the rest of the houses in town: it rests on pillars and it’s made of wood. But he explained that the difference is its pillars and rafters were carved with axes, it has “round-headed” shingles, much appreciated for their decorative value, and the timber comes from Guaitecas cypress, once abundant in the region and now very rare. The cypresses of Chiloé can live for more than three thousand years, and are among the longest-lived trees in the world, after the baobabs of Africa and the sequoias of California.

The house has a high-ceilinged living room, where everything happens around the big, black, and imposing wood stove, which is used to heat the place and for cooking. There are two bedrooms, a medium-sized one, which is Manuel’s, and a smaller one, mine, as well as a bathroom with a sink and a shower. There is not a single door inside the house, but the washroom has a striped wool blanket hanging across the threshold, for privacy. In the part of the main room used as the kitchen there’s a big table, a cupboard and a deep crate with a lid to store potatoes, which in Chiloé are eaten at every meal; bunches of herbs, braids of chilies and garlic, long dry pork sausages and heavy iron pots and pans for cooking over wood fires all hang from the ceiling. A ladder leads up to the attic, where Manuel keeps most of his books and files. There are no paintings, photographs or ornaments on the walls, nothing personal, only maps of the archipelago and a beautiful ship’s clock with a bronze dial set in mahogany, that looks like it was salvaged from the Titanic. Outside Manuel has improvised a primitive jacuzzi with a huge wooden barrel. The tools, firewood, charcoal and drums of gasoline for the motorboat and the generator are kept in the shed out back.

My room is simple like the rest of the house; there’s one narrow bed covered with a blanket similar to the washroom curtain, a chair, a dresser with three drawers and a few nails in the wall to hang clothes from. More than enough for my possessions, which fit easily into my backpack. I like this austere and masculine atmosphere, the only worrying thing is Manuel Arias’ obsessive tidiness; I’m more relaxed.

The men put the refrigerator in its place, hooked it up to the gas and then settled down to share a couple of bottles of wine and a salmon that Manuel had smoked the previous week in a metal drum with apple wood. Looking out at the sea from the window, they ate and drank in silence, the only words they pronounced were an elaborate and ceremonious series of toasts: “Salud! Good health!” “May this drink bring you good health.” “And the same I wish to you.” “May you live many more years.” “May you attend my funeral.” Manuel gave me sidelong, uncomfortable glances until I took him aside to tell him to calm down, that I wasn’t planning on making a grab for the bottles. My grandmother had surely warned him and he’d been planning to hide the liquor; but that would be absurd, the problem isn’t alcohol, it’s me.

Meanwhile Fahkeen and the cats were sizing each other up cautiously, dividing up the territory. The tabby is called Dumb-Cat, because the poor animal is stupid, and the ginger one is the Literati-Cat, because his favorite spot is on top of the computer; Manuel says he knows how to read.

The men finished the salmon and the wine, said goodbye and left. I noticed that Manuel never even hinted at paying them, as he hadn’t either with the others who’d helped move the refrigerator before, but it would have been indiscreet of me to ask him about it.

I looked over Manuel’s office, composed of two desks, a filing cabinet, book shelves, a modern computer with a double monitor, fax and printer. There was an internet connection, but he reminded me — as if I could forget — that I’m incommunicado. He added, defensively, that he has all his work on that computer and prefers that no one touch it.

“What do you do?” I asked him.

“I’m an anthropologist.”

“Anthropophagus?”

“I study people, I don’t eat them,” he told me.

“It was a joke, man. Anthropologists don’t have any raw material anymore; even the most savage tribesman has a cell phone and a television these days.”

“I don’t specialize in savages. I’m writing a book about the mythology of Chiloé.”

“They pay you for that?”

“Barely,” he admitted.

“It looks like you must be pretty poor.”

“Yes, but I live cheaply.”

“I wouldn’t want to be a burden on you,” I told him.

“You’re going to work to cover your expenses, Maya, that’s what your grandmother and I agreed. You can help me with the book and in March you’ll work with Blanca at the school.”

“I should warn you: I’m very ignorant. I don’t know anything about anything.”

“What do you know how to do?”

“Bake cookies and bread, swim, play soccer and write Samurai poems. You should see my vocabulary! I’m a human dictionary, but in English. I don’t think that’ll be much use to you.”

“We’ll see. The cookies sound promising.” And I think he hid a smile.

“Have you written other books?” I asked yawning; the tiredness of the long trip and the five-hour time difference between California and Chile was weighing on me like a ton of bricks.

“Nothing that might make me famous,” he said pointing to several books on his desk: Dream Worlds of the Australian Aborigines, Initiation Rites among the Tribes of the Orinoco, Mapuche Cosmogony in Southern Chile.

“According to my Nini, Chiloé is magical,” I told him.

“The whole world is magical, Maya,’ he answered.

Manuel Arias assured me that the soul of his house is very ancient. My Nini also believes that houses have memories and feelings, she can sense the vibrations: she knows if the air of a place is charged with bad energy because misfortunes have happened there, or if the energy is positive. Her big house in Berkeley has a good soul. When we get it back we’ll have to fix it up — it’s falling apart from old age — and then I plan to live in it till I die. I grew up there, on the top of a hill, with a view of San Francisco Bay that would be impressive if it weren’t blocked by two thriving pine trees. My Popo never allowed them to be pruned. He said that trees suffer when they’re mutilated and all the vegetation for a thousand meters around them suffers too, because everything is connected in the subsoil. It would be a crime to kill two pines to see a puddle of water that could just as easily be appreciated from the freeway.

The first Paul Ditson bought the house in 1948, the year the racial restriction for acquiring property in Berkeley was abolished. The Ditsons were the first black family in the neighborhood, and the only one for twenty years, until others began moving in. It was built in 1885 by a tycoon who made a lot of money in oranges. When he died he left his fortune to the university and his family in the dark. It was uninhabited for a long time and then passed from hand to hand, deteriorating a bit more with each transaction, until the Ditsons bought it. They were able to repair it because it had a strong framework and good foundations. After his parents died, my Popo bought his brothers’ shares and lived alone in that six-bedroom Victorian relic, crowned with an inexplicable bell tower, where he installed his telescope.

When Nidia and Andy Vidal arrived, he was only using two rooms, the kitchen and the bathroom; the rest he kept closed up. My Nini burst in like a hurricane of renovation, throwing knickknacks in the garbage, cleaning and fumigating, but her ferocity in combatting the havoc was not strong enough to conquer her husband’s endemic chaos. After many fights they made a deal that she could do what she liked with the house, as long as she respected his desk and the tower of the stars.

My Nini felt right in her element in Berkeley, that gritty, radical, extravagant city, with its mix of races and human pelts, with more geniuses and Nobel prize-winners than any other city on earth, saturated with noble causes, intolerant in its sanctimoniousness. My Nini was transformed: before she’d been a prudent and responsible young widow, who tried to go unnoticed, but in Berkeley her true character emerged. She no longer had to dress as a chauffeur, like in Toronto, or succumb to social hypocrisy, like in Chile; no one knew her, she could reinvent herself. She adopted the esthetic of the hippies, who languished on Telegraph Avenue selling their handicrafts surrounded by the aromas of incense and marijuana. She wore tunics, sandals and beads from India, but she was very far from being a hippie: she worked, took on the responsibilities of running a house and raising a granddaughter, participated in the community and I never saw her get high or chant in Sanskrit.

To the scandal of her neighbors, almost all of them her husband’s colleagues, with their dark, ivy-covered, vaguely British residences, my Nini painted the big Ditson house in the psychedelic colors inspired by San Francisco’s Castro Street, where gay people were starting to move in and remodel the old houses. Her violet and green walls, her yellow friezes and garlands of plaster flowers provoked gossip and a couple of citations from the municipality, until the house was photographed for an architecture magazine, and became a landmark for tourists in the city and was soon being imitated by Pakistani restaurants, shops for young people and artists’ studios.

My Nini also put her personal stamp on the interior decoration. She added her artistic touch to the ceremonial pieces of furniture, heavy clocks and horrendous paintings in gilt frames, acquired by the first Ditson: a profusion of lamps with fringes, frayed rugs, Turkish divans and crocheted curtains. My room, painted mango color, had a canopy over the bed made of Indian cotton edged with little mirrors and a flying dragon hanging from the center, who would have killed me if it ever fell and landed on me; on the walls she’d put up photographs of malnourished African children, so I could see how these unfortunate creatures were starving to death, while I refused to eat what I was given. According to my Popo, the dragon and the Biafran children were the cause of my insomnia and lack of appetite.

My guts began to suffer a frontal attack from Chilean bacteria. On my second day on this island I was doubled over in bed with stomach pains and I’m still a little shivery, spending hours in front of the window with a hot water bottle on my belly. My grandmother would say I’m giving my soul time to catch up to me in Chiloé. She thinks jet-travel is not advisable because the soul travels more slowly than the body, falls behind and sometimes gets lost along the way; that must be the reason why pilots, like my dad, are never entirely present: they’re waiting for their soul, which is up in the clouds.

You can’t rent DVDs or videogames here and the only movies are the ones they show once a week at the school. For entertainment I have only Blanca Schnake’s fevered romance novels and books about Chiloé in Spanish, very useful for learning the language, but they’re hard for me to read. Manuel gave me a battery-operated flashlight that fits over the forehead like a miner’s lamp; that’s how we read when the electricity goes off. I can’t say very much about Chiloé, because I’ve barely left this house, but I could fill several pages about Manuel Arias, the cats and the dog, who are now my family, Auntie Blanca, who shows up all the time on the pretext of visiting me, although it’s obvious that she comes to see Manuel, and Juanito Corrales, a boy who also comes every day to read with me and to play with Fahkeen. The dog’s very selective when it comes to company, but he puts up with the kid.

Yesterday I met Juanito’s grandmother. I hadn’t seen her before, because she was at the hospital in Castro, the capital of Chiloé, with her husband, who had a leg amputated in December and isn’t healing very well. Eduvigis Corrales is the color of terracotta, with a cheerful face crisscrossed with wrinkles, stocky and short legged, a typical Chilota. She wears her hair in a thin braid wrapped around her head and dresses like a missionary, with a thick skirt and lumberjack boots. She looks about sixty years old, but she’s only forty-five; people age quickly here and live a long time. She arrived with an iron pot, as heavy as a cannon, that she put on the stove to heat up, while she gave me a hasty speech, something about introducing herself with the proper respect, she was Eduvigis Corrales, the gentleman’s neighbor and cleaning lady. “Hey! What a beautiful big girl, this gringuita! Watch over her, Jesus! The gentleman was waiting for you, dear, like everybody else on the island, and I hope you like the little chicken with potatoes I made for you.” It wasn’t a local dialect, which is what I thought at first, but Spanish at a gallop. I deduced that Manuel Arias was the gentleman, although Eduvigis was talking about him in the third person, as if he weren’t there.

Eduvigis speaks to me, however, in the same bossy tone as my grandmother. This good woman comes to clean the house, takes the dirty laundry away and brings it all back clean, splits firewood with an axe so heavy I couldn’t even lift it, grows crops on her land, milks her cow, sheers sheep and knows how to slaughter pigs, but doesn’t go out fishing or to collect seafood because of her arthritis, she explained. She says her husband is not such a bad sort, not as bad as people in town think, but the diabetes really got him down and since he lost his leg he just wants to die. Of her five living children, only one is still at home, Azucena, who’s thirteen, and she also has her grandson Juanito, who’s ten, but looks younger “cuz he was born espirituado,” as she explained to me. This being espirituado might mean mental feebleness or that the one affected possesses more spirit than matter; in Juanito’s case it must be the second, because there’s nothing stupid about him.

Eduvigis lives on the produce of her small piece of land, what Manuel pays for her help and the money her daughter, Juanito’s mother, who works at a salmon farm in the south of the Isla Grande sends. In Chiloé the salmon-farming industry was the second largest in the world, after Norway’s, and boosted the region’s economy, but it contaminated the seabed, put the traditional fishermen out of business and tore families apart. Now the industry is ruined, Manuel explained, because they put too many fish in the cages and gave them so many antibiotics, that when they were attacked by a virus they couldn’t be saved; their immune systems didn’t work anymore. There are twenty thousand unemployed from the salmon farms, most of them women, but Eduvigis’s daughter still has a job.

Soon we sat down to eat. As soon as she took the lid off the pot and the fragrance reached my nostrils, I was transported back to the kitchen of my childhood, in my grandparents’ house, and my eyes misted up with nostalgia. Eduvigis’s chicken stew was my first solid food for several days. This illness has been embarrassing, it was impossible to conceal the vomiting and diarrhea in a house with no doors. I asked Manuel what had happened to the doors and he replied that he preferred open spaces. I got sick from Blanca Schnake’s clams or the myrtle-berry pie, I’m sure. At first, Manuel pretended he didn’t hear the noises coming out of the washroom, but soon he had to drop the facade, because he saw me so weak. I heard him talking on his cell phone to Blanca to ask for instructions and then he started making rice soup, changed my sheets and brought me a hot water bottle. He keeps watch over me out of the corner of his eye without a word, but he’s alert to my needs. At my slightest attempt to thank him he reacts with a grunt. He also phoned Liliana Treviño, the local nurse, a short, compact, young woman, with contagious laughter and an indomitable mane of curly hair, who gave me some enormous charcoal tablets, black, scratchy, and very hard to swallow. Seeing they had absolutely no effect, Manuel got the greengrocer’s little cart to take me into town to see a doctor.

On Thursdays the National Health Services boat, which travels around the islands, stops here. The doctor looked like a fourteen-year-old, near-sighted kid, who didn’t even need to shave yet, but it just took him a single glance to diagnose my condition: “You’ve got chilenitis, what foreigners get when they come to Chile. Nothing serious,” and he gave me a few pills in a twist of paper. Eduvigis made me an infusion of herbs, because she doesn’t trust remedies from the pharmacy, says they’re a shady deal from American corporations. I’ve been taking the infusion conscientiously, and it’s making me feel better. I like Eduvigis Corrales, she talks and talks like Auntie Blanca; the rest of the people around here are taciturn.

I told Juanito Corrales that my mother was a princess of Lapland since he was curious about my family. Manuel was at his desk and didn’t make any comments, but after the boy left he told me that the Sami people, who live in Lapland, don’t have royalty. We’d just sat down at the table, a plate of sole with butter and cilantro for him and a clear broth for me. I explained that the thing about the Laplander princess had occurred to my Nini in a moment of inspiration when I was five and started noticing the mystery surrounding my mother. I remember we were in the kitchen, the coziest room in the house, baking cookies like we did every week for Mike O’Kelly’s delinquents and drug addicts. Mike is my Nini’s best friend, who is intent on achieving the impossible task of saving young people who’ve gone astray. He’s a real Irishman, Dublin-born, with skin so white, hair so black and eyes so blue, that my Popo nicknamed him Snow-White, after that gullible girl that ate the poisoned apple in that Walt Disney movie. I’m not saying that O’Kelly is gullible; quite the contrary, he’s smart as can be: he’s the only one who can shut my Nini up. There was a Laplander princess in one of my books. I had a serious library at my disposal, because my Popo believed that culture entered by osmosis and it was better to start early, but my favorite books were fairy tales. According to my Popo, children’s stories are racist, how can it be that fairies don’t exist in Botswana or Guatemala, but he never censored my reading, he would simply give his opinion with the aim of developing my capacity for critical thought. My Nini, on the other hand, never appreciated my critical thoughts and used to discourage them with smacks on the head.

In a picture of my family that I painted in kindergarten, I put my grandparents in full color in the center of the page and way over on one side I added a fly — my dad’s plane — and a crown on the other representing my blue-blooded mother. In case there were any doubts, the next day I took my book, where the princess appeared in an ermine cape riding a white bear. The whole class laughed at me in unison. Later, back at home, I put the book in the oven with the corn pie, which is baked at 350º. After the firefighters left and the cloud of smoke began to lift, my grandmother bombarded me with the usual shouts of “you little shit!“ while my Popo tried to rescue me before she ripped my head off. Between hiccups, with snot running down my face, I told my grandparents that at school they’d nicknamed me “the orphan of Lapland”. My Nini, in one of her sudden mood changes, squeezed me against her papaya breasts and assured me there was nothing orphaned about me, I had a father and grandparents, and the next swine who dared to insult me was going to have to deal with the Chilean mafia. This mafia was composed of her alone, but Mike O’Kelly and I were so afraid of her, that we called my Nini Don Corleone.

My grandparents pulled me out of kindergarten and for a while taught me the basics of coloring and making worms out of playdoh at home, until my dad returned from one of his trips and decided that I needed to socialize with people my own age, not only with O’Kelly’s drug addicts, apathetic hippies and the implacable feminists who were drawn to my grandmother. The new school was in two old houses joined by a second-floor bridge with a roof, an architectural challenge held aloft by the effect of its curvature, like cathedral domes, according to my Popo’s explanation, although I hadn’t asked. They taught using an Italian system of experimental education in which the students did whatever the fuck we wanted. The classrooms had no blackboards or desks, we sat on the floor, the teachers didn’t wear bras or shoes and everyone learned at their own pace. My dad might have preferred a military academy, but he didn’t interfere with my grandparents’ decision, since it would be up to them to deal with my teachers and help with my homework.

“This kid’s retarded,” decided my Nini when she saw how slowly I was learning. Her vocabulary is peppered with politically unacceptable expressions, like retard, fatso, dwarf, hunchback, faggot, butch, chinkie-rike-eat-lice and lots more that my grandfather tried to put down to the limitations of his wife’s English. She’s the only person in Berkeley who says black instead of Afro-American. According to my Popo, I wasn’t deficient mentally, but rather imaginative, which is less serious, and time proved him right, because as soon as I learned my alphabet I began to read voraciously and to fill up notebooks with pretentious poems and an invented sad and bitter story of my life. I’d realized that in writing happiness is useless — without suffering there is no story — and I secretly savored the nickname of orphan, because the only orphans on my radar were those from classic tales, and they were all very wretched.

My mother, Marta Otter, the improbable Laplander princess, disappeared into the Scandinavian mists before I could even catch her scent. I had a dozen photographs of her and a present she sent by mail for my fourth birthday, a mermaid sitting on a rock inside a glass ball, where it looked like it was snowing when you shook it. That ball was my most precious treasure until I was eight, when it suddenly lost its sentimental value, but that’s another story.

I’m furious because my only valuable possession has disappeared, my civilized music, my iPod. I think Juanito Corrales took it. I didn’t want to make trouble for him, poor kid, but I had to tell Manuel, who didn’t think it was a big deal; he said Juanito’ll use it for a few days and then put it back where it was. That’s the way things work in Chiloé, it seems. Last Wednesday someone brought back an axe that had been taken without permission from the woodshed more than a week before. Manuel suspected he knew who had it, but it would have been an insult to ask for it back, since borrowing is one thing and theft is something else altogether. Chilotes, descendants of dignified indigenous people and haughty Spaniards, are proud. The man who had the axe gave no explanations, but brought a sack of potatoes as a gift, which he left on the patio before settling down with Manuel to drink chicha de manzana, a rustic apple cider, and watch the flight of seagulls from the porch. Something similar happened with a relative of the Corrales, who works on Isla Grande and came here to get married before Christmas. Eduvigis gave him the key to this house so that, in Manuel’s absence, while he was in Santiago, they could take his stereo system to liven up the wedding. When he came home, Manuel found to his surprise that his stereo had vanished, but instead of informing the carabineros, he waited patiently. There are no serious thieves on the island and those who come from elsewhere would have a hard time getting away with something so bulky. A little while later Eduvigis recovered what her relative had borrowed and returned it along with a basket of seafood. Manuel has his stereo back, so I guess I’ll see my iPod again.

Manuel prefers to be quiet, but he’s realized that the silence of this house might be excessive for a normal person and he makes efforts to chat with me. From my room, I heard him talking to Blanca Schnake in the kitchen. “Don’t be so gruff with the gringuita, Manuel. Can’t you see how lonely she is? You have to talk to her,” she advised him. “What do you want me to say to her, Blanca? She’s like a Martian,” he muttered, but he must have thought it over, because now instead of overwhelming me with academic lectures on anthropology, like he did at first, he asks about my past and so, bit by bit, we’re starting to exchange ideas and get to know each other.

My Spanish is very faltering, but his English is fluent, though with an Australian accent and Chilean intonation. We agreed that I should practice, so we normally try to speak in Spanish, but we soon start to mix the two languages in the same sentence and end up in Spanglish. If we’re mad at each other, he speaks to me in clearly enunciated Spanish, to make himself understood, and I shout at him in street gang English to scare him.

Manuel doesn’t talk about himself. The little I know about him I’ve guessed or heard from Auntie Blanca. There is something strange in his life. His past must be even more turbulent than mine, because many nights I’ve heard him moan and struggle in his sleep: “Get me out of here! Let me out!” Everything can be heard through these thin walls. My first impulse is to go and wake him up, but I don’t dare enter his room; the lack of doors forces me to be prudent. His nightmares invoke evil presences, the house seems to fill with demons. Even Fahkeen gets uneasy and trembles, right up against me in bed.

My work for Manuel Arias couldn’t be easier. It consists of transcribing his recordings of interviews and typing up his notes for the book. He’s so tidy, that if I move an insignificant little piece of paper on his desk the blood drains from his face. “You should feel very honored, Maya, because you’re the first and only person I’ve ever allowed to set foot in my office. I hope you won’t make me regret it,” he had the nerve to say to me, when I threw out last year’s calendar. I dug it out of the garbage intact, except for a few spaghetti stains, and stuck it up on the computer screen with chewing gum. He didn’t speak to me for twenty-six hours.

His book on magic in Chiloé has me so hooked it keeps me from sleeping. (Only in a manner of speaking since the slightest silliness keeps me from sleeping.) I’m not superstitious, like my Nini, but I accept that the world is a mysterious place and anything’s possible. Manuel has a whole chapter on the Mayoría, or the Recta Provincia, as the rule of the much-feared brujos – witches and sorcerers – of these lands was called. On our island the Mirandas are rumored to be a family of brujos and people cross themselves or keep their fingers crossed when they walk past Rigoberto Miranda’s house. He’s a fisherman by trade, and related to Eduvigis Corrales. His last name is as suspicious as his good luck is: fish fight to be caught in his nets, even when the sea is black, and his only cow has given birth to twins twice in three years. They say that Rigoberto Miranda has a macuñ, a bodice made from the skin of the chest of a corpse, for flying at night, but no one’s seen it. It’s advisable to slash dead people’s chests with a knife or a sharp stone so they won’t suffer the indignity of ending up turned into a waistcoat.

Brujos fly, they can do a lot of evil, kill with their minds and turn into animals, none of which I can really see Rigoberto Miranda doing. He’s a shy man who often brings Manuel crabs. But my opinion doesn’t count, I’m an ignorant gringa. Eduvigis warned me that when Rigoberto Miranda comes over I have to cross my fingers before I let him in the house, in case he casts some spell. Those who’ve never suffered from witchcraft first-hand tend to be skeptical, but as soon as something strange happens they run to the nearest machi, an indigenous healer. Let’s say a family around here starts coughing too much; then the machi will look for a basilisk or cockatrice, an evil reptile hatched from the egg of an old rooster, staying under the house that comes up at night and sucks the air out of the people sleeping there.

The most delectable stories and anecdotes come from the really old people, on the most remote islands of the archipelago, where the same beliefs and customs have held sway for centuries. Manuel doesn’t only get information from the elderly, but also from journalists, teachers, booksellers, and shopkeepers, who make fun of brujos and magic, but wouldn’t dare venture into a cemetery at night. Blanca Schnake says that her father, when he was young, saw the entrance to the mythical cave where the brujos gathered, in the peaceful village of Quicaví, but in 1960 an earthquake shifted the land and the sea and since then no one has been able to find it.

The guardians of the cave are invunches, horrifying beings formed by the brujos from first-born male babies, kidnapped before baptism. The method for transforming the baby into an invunche is as macabre as it is improbable: they break one of his legs, twist it and stick it under the skin of his back, so he’ll only be able to get around on three limbs and won’t escape; then they apply an ointment that makes him grow a thick hide, like a billy goat’s; they split his tongue like a snake’s and feed him on the rotted flesh of a female corpse and the milk of an Indian woman. In comparison, a zombie can consider itself lucky. I wonder what kind of depraved mind comes up with horrific ideas like that.

Manuel’s theory is that the Recta Provincia or Mayoría, as it’s also called, had its origins as a political system. Since the eighteenth century, the indigenous people of the region, the Huilliche, rebelled against Spanish rule and later against the Chilean authorities; they supposedly formed a clandestine government copied from the Spanish and Jesuit administrative style, divided the territory into kingdoms and appointed presidents, scribes, judges, etc. There were thirteen principal sorcerers, who obeyed the King of the Recta Province, the Above Ground King and the Below Ground King. Since it was indispensable to keep it secret and control the population, the Mayoría created a climate of superstitious fear and that’s how a political strategy eventually turned into a tradition of magic.

In 1880 they arrested several people accused of witchcraft, tried them in Ancud and had them executed, with the aim of breaking the back of the Mayoría, but nobody is sure they achieved their objective.

“Do you believe in witches?” I asked Manuel.

“No, but it’s irrational to rule out the irrational.”

“Tell me! Yes or no?”

“It’s impossible to prove a negative, Maya, but calm down, I’ve lived here for many years and the only witch I know is Blanca.”

Blanca doesn’t believe in any of this. She told me invunches were invented by the missionaries to convince the families of Chiloé to baptize their children, but that strikes me as going too far, even for Jesuits.

“Who is this Mike O’Kelly? I received an incomprehensible message from him,” Manuel told me.

“Oh, Snow White wrote to you! He’s a good old, completely trustworthy Irish friend of the family. It must be my Nini’s idea to communicate with us through him, for safety’s sake. Can I answer him?”

“Not directly, but I can send him a message on your behalf.”

“These precautions are exaggerated, Manuel, what can I say.”

“Your grandmother must have good reason to be so cautious.

“My grandma and Mike O’Kelly are members of the Club of Criminals and they’d pay gold to be mixed up in a real crime, but they have to content themselves with playing at bandits.”

“What kind of club is that?” he asked me, looking worried.

I explained it starting from the beginning. The Berkeley county library hired my Nini, eleven years before my birth, to tell stories to children, as a way of keeping them busy after school until their parents finished work. A little while later she proposed to the library the idea of sessions of detective stories for adults, and it was accepted. Then she and Mike O’Kelly founded the Club of Criminals, as it’s called, although the library promotes it as the Noir Novels Club. During the children’s stories hour, I used to be just one of the kids hanging on my grandma’s every word and sometimes, when she had no one to leave me with, she’d also take me to the library for the adults’ hour. Sitting on a cushion, with her legs crossed like a fakir, my Nini asked the children what they wanted to hear, someone suggested a theme and she improvised something in less than ten seconds. My Nini has always been annoyed by the contrived need for a happy ending to stories for children; she believes that in life there are no endings, just thresholds, people wandering here and there, stumbling and getting lost. All that rewarding the hero and punishing the villain strikes her as a limitation, but to keep her job she had to stick to the traditional formula, the witch can’t poison the maiden with impunity and marry the prince in a white gown. My Nini prefers an adult audience, because gruesome murders don’t require a happy ending. She’s very well versed in her subject, she’s read every police case and manual of forensic medicine in existence, and claims that she and Mike O’Kelly could carry out an autopsy on the kitchen table with the greatest of ease.

The Criminals’ Club consists of a group of lovers of detective novels, inoffensive people who devote their free time to planning monstrous homicides. It began discreetly in the Berkeley library and now, thanks to the internet, it has global reach. It’s entirely financed by the members, but since they meet in a public building, indignant voices have been raised in the local press alleging that crime is being encouraged with taxpayers’ money. “I don’t know what they’re complaining about. Isn’t it better to talk about crimes that to commit them?” my Nini argued to the mayor, when he called her to his office to discuss the problem.

My Nini’s friendship with Mike O’Kelly began in a second-hand bookstore, where both were absorbed in the detective fiction section. She had been married to my Popo for a short time and he was a student at the university, he was still walking on two legs and hadn’t given a thought to becoming a social activist or to devoting his life to rescuing young delinquents from the streets and from prison. As long as I can remember, my grandma has baked cookies for O’Kelly’s kids, most of them black or Latino, the poorest people in the San Francisco Bay area. When I was old enough to interpret certain signs, I guessed that the Irishman was in love with my Nini, even though he’s twelve years younger than her and she would never have even considered being unfaithful to my Popo. It’s a platonic love story straight out of a Victorian novel.

Mike O’Kelly became famous when they made a documentary about his life. He took two bullets in the back for protecting a gangster kid and ended up in a wheelchair, but that didn’t keep him from continuing his mission. He can take a few steps with a walker and he drives a special car; that’s how he gets around the roughest neighborhoods saving souls, and he’s always the first to show up at any protest that gets going in the streets of Berkeley and the surrounding area. His friendship with my Nini strengthens with every wacky cause they embrace together. They both had the idea that the restaurants of Berkeley should donate leftover food to the city’s homeless, crazies and drug addicts. She got hold of a trailer to distribute it and he recruited the volunteers to serve it. On the television news they showed destitute people choosing between sushi, curry, duck with truffles and vegetarian dishes from the menu. Quite a few of them complained about the quality of the coffee. Soon the line-ups grew long with middle class customers ready to eat without paying, there were confrontations between the original clientele and those taking advantage and O’Kelly had to bring his boys in to sort them out before the police did. Finally the Department of Health prohibited the distribution of leftovers, because someone had an allergic reaction and almost died from the Thai peanut sauce.

The Irishman and my Nini get together often to analyze gruesome murders over tea and scones. “Do you think a chopped up body could be dissolved in drain-cleaner?” would be a typical O’Kelly question. “It would depend on the size of the pieces,” my Nini might say and the two of them would proceed to prove it by soaking a pound of pork chops in Drano, while I would have to make notes of the results.

“It doesn’t surprise me they’ve conspired to keep me incommunicado at the bottom of the world,” I told Manuel Arias.

“From the sounds of things, they’re scarier than your supposed enemies, Maya,” he answered.

“Don’t underestimate my enemies, Manuel.”

“Did your grandfather soak chops in drain-cleaner too?”

“No, he wasn’t into crimes, just stars and music. He was a third-generation jazz and classical music lover.”

I told him how my grandfather taught me to dance as soon as I could stay upright and bought me a piano when I was five, because my Nini expected me to be a child prodigy and compete on television talent shows. My grandparents put up with my thunderous keyboard exercises, until the piano teacher told them my efforts would be better spent on something that didn’t require a good ear. I immediately opted for soccer, as Americans call proper football, an activity that my Nini thinks is silly: eleven grown men in shorts chasing after a ball. My Popo knew nothing of this sport, because it’s not very popular in the United States, and although he was a baseball fanatic, he didn’t hesitate to abandon his own favorite sport in order to sit through hundreds of little girls’ soccer games. Thanks to some colleagues at the Sao Paulo observatory, he got me an autographed poster of Pelé, who was long-retired and living in Brazil. My Nini spent her efforts in getting me to read and write like an adult, since it was obvious I wasn’t going to be a musical prodigy. She signed me up as a library member, made me copy paragraphs of classic books and thwacked me on the head if she caught a spelling mistake or if I got a mediocre mark in English or literature, the only subjects that interested her.

“My Nini has always been rough, Manuel, but my Popo was a sweetie, he was the light of my life. When Marta Otter left me at my grandparent’s house, he held me very carefully against his chest, because he’d never had a newborn in his arms before. He said the affection he felt for me left him dazed. That’s what he told me and I’ve never doubted his love.

Once I start talking about my Popo, there’s no way to shut me up. I explained to Manuel that I owe my love for books and my rather impressive vocabulary to my Nini, but everything else I owe to my grandpa. My Nini forced me to study, saying “spare the rod and spoil the child,” or something just as barbarous, but he turned learning into a game. One of those games consisted in opening the dictionary at random, closing your eyes, pointing to a word and then guessing what it means. We also used to play stupid questions: Why does the rain fall down, Popo? Because if it fell up your underwear would get wet, Maya. Why is glass transparent? To confuse the flies. Why are your hands black on top and pink underneath, Popo? Because the paint ran out. And we’d go on like that until my grandma ran out of patience and started howling.

My Popo’s immense presence, with his sarcastic sense of humor, his infinite goodness, his innocence, his belly to rock me to sleep and his tenderness, filled my childhood. He had a booming laugh that bubbled up from the bowels of the earth and shook him from head to toe. “Popo, swear to me that you’ll never ever die,” I used to demand at least once a week and his reply never varied: “I swear I’ll always be with you.” He tried to come home early from the university to spend some time with me before going up to his desk and his big fat astronomy books and his star charts, preparing his classes, correcting proofs, researching, writing. His students and colleagues would visit and they’d shut themselves up to exchange splendid and improbable ideas until dawn, when my Nini would interrupt in her nightie with a big thermos of coffee. “Your aura’s getting dull, old man. Don’t forget you’ve got to teach at eight,” and she’d proceed to pour out coffee and push the visitors toward the door. The dominant color of my grandfather’s aura was violet, very appropriate, because it’s the color of sensibility, wisdom, intuition, psychic power, and vision of the future. These were the only times my Nini entered his office; whereas I had free access and even had my own chair and a corner of the desk to do my homework, to the rhythm of smooth jazz and the smell of pipe tobacco.