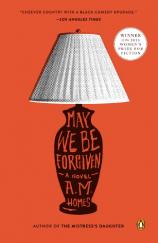

May We Be Forgiven

Review

May We Be Forgiven

In novels like THE END OF ALICE and MUSIC FOR TORCHING, A.M. Homes hasn’t shied away from grim subjects, pedophilia and school gun violence only two of them. Her new novel returns to familiar territory --- the American suburbs --- to tell a powerful story of despair and redemption, all the while probing what she’s consistently sought to expose, in the vein worked by writers like Richard Yates and John Cheever, as the real heart of darkness at the core of suburban life.

Homes observed in a recent interview that “Despite the sense that things are looking up now, there remains an ongoing level of discomfort, an unarticulated anxiety about what will ‘go wrong’ next.” That’s the spirit that looms over this story. It begins with two violent acts perpetrated by George Silver, a prominent television executive with anger management issues and the younger brother of Harold Silver, the story’s narrator. The first is a car accident that kills a mother and father, leaving behind their young son. The second, George’s murder of his wife when he returns home to find her in bed with Harold, launches Homes’ protagonist on a lurching journey of self-discovery.

Though the disasters that cascade over Harold (divorce, illness and job loss only a few of them) at times rises almost to a Job-like level, that’s where the similarities to the biblical character end. On his own behalf the most he can say is, “Before this happened, I had a life, or at least I thought I did; the quality, the successfulness of it had not been called into question.” Clearly, he’s more acted upon than actor.

"Homes' new novel returns to familiar territory --- the American suburbs --- to tell a powerful story of despair and redemption, all the while probing what she’s consistently sought to expose, in the vein worked by writers like Richard Yates and John Cheever, as the real heart of darkness at the core of suburban life."

In contrast to his outwardly successful brother, Harold is a historian specializing in the study of Richard Nixon, a man he considers “the bridge between our prewar Depression-era culture and the postwar prosperous-American-dream America.” He’s toiled for years on a Nixon monograph that’s grown to 1,300 pages, but it’s only the discovery of a cache of short stories written by the disgraced president that offers him a glimpse of professional relevance. Grimly determined to teach disengaged students about events like the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Watergate scandal, Harold is informed by his department chair that the traditional view of history instruction must be abandoned for one that’s “future-forward,” in which students explore the “world of possibility,” not the fossilized past.

With his sister-in-law dead and his brother incarcerated, Harold moves into their Westchester County home to assume custody of Nate and Ashley, their adolescent children. In the Thanksgiving dinner that opens the novel (it closes on that holiday a year later), Harold observes them as they “sat like lumps at the table, hunched, or more like curled, as if poured into their chairs, truly spineless, eyes focused on their small screens, the only thing in motion their thumbs.” What quickly becomes clear, though, is that their emotional intelligence is more highly developed than any of the adult characters. At their urging, Harold brings Ricardo, the young survivor of the car accident, into the household. That decision, along with Harold’s deepening sense of responsibility for these children, so damaged by the acts of self-absorbed “grownups,” allows Homes to roam the landscape of our fractured, hybrid families, contrasting them with the genetic legacy that’s contributed to some of the Silvers brothers’ dysfunctional behavior.

Only a writer of Homes’ sensibilities would anchor her protagonist’s redemption in Internet sex. Cheryl, the housewife Harold meets in that venue, becomes an odd sort of conscience, pushing him toward becoming a better version of himself, as she’s urging him on to more misbehavior. In the way it exposes the tortured soul of its narrator, MAY WE BE FORGIVEN is a spiritual cousin to novels like Joseph Heller’s SOMETHING HAPPENED, Don DeLillo’s WHITE NOISE and Jonathan Franzen’s THE CORRECTIONS.

Homes administers frequent doses of humor to leaven the seriousness of her concerns. That wit is deployed, not to mock or amuse, but instead to reflect our lives back to us in a fresh, often startling, way. Whether it’s a swingers’ club gathered at a suburban strip mall for a night of laser tag, some bizarre permutations of the American correctional system or the ministrations of an event planner arranging a South African bar mitzvah that’s among the most unusual in the history of Judaism, Homes displays her penchant for putting a distinctive spin on the oddities of contemporary culture. That’s a talent that can’t be underestimated in a time when every day’s news brings stories more inconceivable than anything conjured out of the imagination of the most talented writer of what passes for realist fiction.

And it’s a reminder that, despite her book's title, Homes is a social satirist, not a moralist. Even with her sometimes painful bite, she demonstrates real compassion for her characters, and it’s that depth of feeling that keeps us engrossed in their story. Because the truth is that for all its unsentimental, at times cynical, view of the current American psyche, at the end of this wild ride Homes’ take on our current predicament is a fundamentally optimistic one.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg on October 5, 2012

May We Be Forgiven

- Publication Date: September 24, 2013

- Genres: Fiction

- Paperback: 496 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- ISBN-10: 014750970X

- ISBN-13: 9780147509703