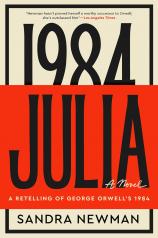

Julia

Review

Julia

If you're like me, it's been a while since you've read George Orwell's 1984. The good news is that as soon as you pick up Sandra Newman's JULIA --- a feminist reimagining of that classic novel --- everything you remember about 1984 is likely to come flooding back. That's partly a testament to Newman's skillful writing, which in some sections lifts whole passages from the original (more on that below), but partly, of course, a tribute to the indelibility of Orwell's prescient, nightmarish vision of a future that still feels all too relevant.

Winston Smith, if you recall, was the protagonist of Orwell's novel, and Julia was the lover whom he betrayed when tortured and confronted by his greatest fear. In Newman's version of events (which was authorized by the Orwell estate), Winston is a secondary character, and the focus is on Julia.

"Apart from being a satisfying character study, Newman's novel feels not like a throwback to Orwell's 1949 book but rather like a thoroughly contemporary commentary on today's concerns about digital surveillance, artificial intelligence and the increasingly difficult project of discerning truth from fiction."

Julia is an exemplary member of society, having overcome her questionable roots in the Semi-Autonomous Zone of Kent to become a mechanic in the Fiction department of the Ministry of Truth. She is largely indifferent to the Party's propaganda, but instead has devised her own methods for surviving and thriving in this ultra-totalitarian state, understanding its systems well enough to know how to cannily work within them for her own ends. She has no intention of overthrowing anything as she is largely content with pursuing her own self-interest. However, things are thrown into question when she finds an unsigned note reading "I love you" in her locker.

Soon Julia is caught up in a plot to undermine skeptics of the regime (all while having the Party's permission to indulge in as much sexual activity as she'd like). Then she's recruited for the so-called "Big Future" project to bear Big Brother's child, which she's sure will grant her the kind of special status she never thought she deserved and certainly didn't think she wanted. But no one is safe in this society, and just as in Orwell's novel, betrayals come from surprising sources.

Apart from being a satisfying character study, Newman's novel feels not like a throwback to Orwell's 1949 book but rather like a thoroughly contemporary commentary on today's concerns about digital surveillance, artificial intelligence and the increasingly difficult project of discerning truth from fiction. Although JULIA stands entirely on its own merits, reading the sections of the novel that include Winston Smith side-by-side with 1984 is almost like a master class in literary perspective. Where Orwell's Smith sees a woman who's largely a cipher (and his character is fine with that), Newman fills in the gaps, giving Julia's character depth and color while obliquely pointing out Smith's (and Orwell's?) blind spots.

Reading these two books together would be a fascinating book club project, as would reading JULIA alongside Anna Funder's recent biography, WIFEDOM, which is about Orwell's wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy. Both prompt questions about the ways in which women contribute to, and are erased from, Orwell's undoubtedly influential literary works.

Reviewed by Norah Piehl on October 28, 2023