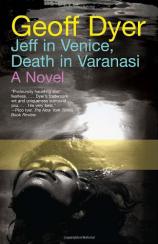

Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi

Review

Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi

Geoff Dyer’s fourth work of fiction is a brilliantly

bifurcated exploration of the emotional poles of sensual pleasure

and spiritual quest. It’s a smart, funny, eyes-wide-open take

on our search for meaning, one of those rare novels that begs to be

read again the moment you have turned to the final page.

In the novel’s first half, “Jeff in Venice,”

Dyer introduces Jeff Atman (in a sly nod to the second part of the

book, the word means “soul” or “true self”

in Hinduism), a cynical 45-year-old British journalist who has just

dyed his hair for the first time and taken off for Venice. He is

headed there on assignment to cover the Biennale and write a piece

on the ex-girlfriend of a prominent artist (the latter a task he

bungles spectacularly). Jeff seems more intent on sampling the

pleasures of the Italian city (a torrent of bellinis and

never-ending helpings of risotto the most prominent). There, he

meets Laura Freeman, a ravishing young woman who works for a Los

Angeles art gallery. The two zip around the city’s waterways

on its fleet of vaporettos and quickly tumble into a relationship

that features copious bouts of sex (described in NC-17 detail) and

cocaine, interspersed with a mind-numbing swirl of parties and

gallery visits.

Astonished by the ample, unanticipated pleasures of his

encounter with Laura, Jeff strides the streets, dumbly celebrating

his good fortune: “He swaggered through Venice as if he owned

the place, as if it had been created entirely for his benefit.

Life! So full of inconvenience, irritation, boredom and annoyance

and yet, at the same time, so utterly fantastic.” Though it

seems the two have made a connection that transcends the purely

carnal, Laura departs for Los Angeles after three magical, if

inexplicable, days. They enact the obligatory exchange of email

addresses and phone numbers, and we’re left with a feeling

that seems both inevitable and somehow fitting that they’ll

never see each other again.

The second section of the book, recounted in the first person by

an unnamed narrator with enough similarities to Jeff to let us

conclude it’s the same protagonist, is set in India’s

holy city of Varanasi, on the banks of the Ganges River. After

polishing off the magazine piece that has brought him there, the

narrator abandons any plan to return home, slowly adapting to the

rituals and rhythms of the ancient city (“I’d come to

Varanasi because there was nothing to keep me in London, and I

stayed on for the same reason: because there was nothing to go home

for.”). But as he does so, he undergoes an emotional

transformation that becomes more profound as time glides past like

the spiritually pure, dreadfully polluted Ganges. “All

I’m saying,” he concludes, “is that in Varanasi I

no longer felt like I was waiting. The waiting was over. I was

over. I had taken myself out of the equation.” He shaves his

head, dons a dhoti and in one of the most striking demonstrations

of Dyer’s art, we ponder whether “Jeff” is

evolving toward some higher plane of spiritual ecstasy or

descending into the depths of madness.

The novel is suffused with a sharp, picturesque description of

its disparate yet strikingly similar settings. “Every day,

for hundreds of years,” Dyer writes, “Venice had woken

up and put on this guise of being a real place even though everyone

knew it existed only for tourists.” Varanasi, with its

ubiquitous ghats and their cremation pyres, is drenched in an

almost hallucinatory swirl of colors, sights and smells: “The

colours made the rainbow look muted. Lolly-pink, a temple pointed

skywards like a rocket whose launch, delayed by centuries, was

still believed possible, even imminent, by the Brahmins lounging in

the warm shade of mushroom umbrellas.”

Given the superficially unconnected stories, it’s fair to

ask whether the work really is a “novel,” or, more

correctly, two novellas with interwoven themes. Regardless, the

effort of teasing out the links between the two sections is one of

the book’s numerous pleasures. To start, both are set in

watery cities steeped in history. And with a deft touch, the

stories’ language and images echo each other, illustrated by

this handful of many such examples: begging bowls, real and

metaphorical appear in both cities; the term “otter”

does double duty as the way Jeff hears Venetians describe the heat

and how “Jeff” imagines his “sleek”

appearance at the end of the novel; there’s an image of a

kangaroo that surfaces at the climax of both stories; and

Jeff’s Venice dream of having his arm devoured by a dog

becomes frighteningly real when that fate befalls a corpse in

Varanasi.

Strikingly contemporary and utterly timeless, JEFF IN VENICE,

DEATH IN VARANASI is an intense, vivid trip to a pair of exotic

cities and an equally provocative journey into the twisted

passageways of the human soul.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg (mwn52@aol.com) on January 22, 2011

Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi

- Publication Date: April 6, 2010

- Genres: Fiction

- Paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Vintage

- ISBN-10: 0307390306

- ISBN-13: 9780307390301