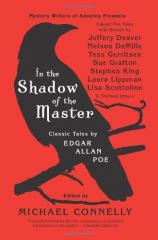

In the Shadow of the Master: Classic Tales by Edgar Allan Poe

Review

In the Shadow of the Master: Classic Tales by Edgar Allan Poe

If you want to understand America through its literature, it is

as essential to read Edgar Allan Poe as it is to read Melville,

Twain or Fitzgerald. For America has always been a land marked by a

belief in our own exceptionalism. America was the “shining

city on the hill,” a positive place of eternal goodness and

promise. Poe told us to hold off a bit on the laurels. His words

took us deep into the darkness and forced us to look whether we

liked it or not. He was the first great American writer to teach us

that maybe stories don’t all have happy endings and

redemption doesn’t always come with the dawn.

This year marks the 200 anniversary of Poe’s birth. But,

as Michael Connelly points out in IN THE SHADOW OF THE MASTER,

“happy” is hardly a word people use in the same

sentence as Poe. Irregardless, the Mystery Writers of America

decided to throw a sort of a birthday party for the dark genius by

gathering 16 of his classic short stories and poems along with

essays from 20 of today’s greatest practitioners of the genre

Poe helped create, including Connelly, Stephen King, Lawrence

Block, Sara Paretsky, Laura Lippman and Nelson DeMille.

The result is a wonderfully accessible and lively volume that

functions well as both a gateway to Poe for the new reader and a

refresher course for those who have not read him since being forced

to in high school.

Poe is probably as well known now as a symbol of the macabre,

for his booze- and drug-dominated lifestyle and for his bizarre

unexplained death at the age of 40 as he is for his actual work. He

is the only American author to have an NFL football team named

after his most famous creation --- a fact that might be as bizarre

as his death.

Well before anybody ever dreamed of “Celebrity

Rehab,” Poe definitely lived his short life on the edge. And

150 years after his death, as Lippman points out here, who else but

Poe has 20 theories circulating about how he died? He was found

delirious on the streets of Baltimore, wearing clothes not his own.

He died soon thereafter, unable to explain what happened to

him.

Baltimore native Lippman’s essay is one of the things that

makes this volume so much fun. Rather than a dry academic analysis,

the contributors often tell us how they discovered Poe’s

work. Several cite the influence of Roger Corman’s B-movie

horror flicks, and one, DeMille, offers a hilarious story about

being trapped in a Long Island graveyard at dusk at the age of 11

after seeing Phantom of the Rue Morgue. Lawrence Block

explains how he uniquely figured out a way to lift the curse, not

cask, of Amontillado to finally win an Edgar Award, which is the

writing prize the Mystery Writers of America bestows each year.

Yet it is the words of Poe himself that still astonish. Not only

do the stories hold up, but the shock they provide you as an adult

is far different from the thrill you might have experienced as a

teenager.

Poe was a revolutionary writer, a true innovator. He invented

the detective novel. His character Dupin was what all fictional

detectives are based on, according to no less an expert than Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle. As King points out here, “The Tell-Tale

Heart” is the first story about a criminal sociopath. And 16

years before Freud was born, Poe was exploring the topic of dual

personalities in “William Wilson” and using an

unreliable narrator in “The Black Cat.”

Poe was not just writing stories; he was writing about

psychology before the field even existed. He was also the first

well-known American to try to make a living as a writer. For those

of us who have followed in his footsteps on that lonely path to

poverty, that might explain his need for a drink on occasion. Poe

made a grand total of $9 for his most famous work, “The

Raven.” I would imagine the Baltimore football franchise

makes considerably more decked out in their purple and black

costumes.

But Poe knew what all good writers know: it is not about the

bling, it is about the work. So Poe used words as a sledgehammer to

create claustrophobic tales filled with existential dread, horror

and death. Every word contributes to the tension, darkness and

madness. Like “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” the

reader is helplessly carried along to an unforgettable climax.

“I will read, and you shall listen; --- and so we will

pass away this terrible night together,” a character gently

says in “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Despite

living in an age when Hollywood grinds out even more graphic

slasher movies each year to shock the young and bored, nothing is

quite as scary as reading Poe alone, perhaps in a strange hotel

room, far from home. Connelly had that experience while researching

one of his novels in Washington, D.C and was literally scared out

of his bed. He writes,

“I’d let him take me to a world of dark imagination,

where common things become uncommon, where the routine becomes the

ghastly unexpected, where a slamming door becomes a shot in the

dark.”

Poe wrote when America was in the early stages of pushing

westward on the road to an Empire that promised universal good. He

demanded that we look inside and face the darkness.

King confesses in his essay that the most common question he is

asked by people is what scares him in fiction. His answer is

“The Tell-Tale Heart” by Poe. King writes, “Here

is a creature who looks like a man but who really belongs to

another species. That’s scary. What elevates this story

beyond merely scary and into the realm of genius, though, is that

Poe foresaw the darkness of generations far beyond his own.”

That says it best.

In his fevered dreams and tortured soul, Poe understood

something about the human heart that future generations of American

writers are still seeking to explore and replicate in their work.

But Poe will always be the master. IN THE SHADOW OF THE MASTER

deserves a place on every bookshelf.

Reviewed by Tom Callahan on January 22, 2011