Excerpt

Excerpt

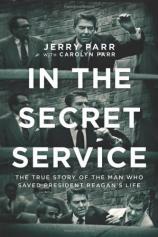

In the Secret Service: The True Story of the Man Who Saved President Reagan's Life

Prolouge

There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.

Graham Greene , The Power and the Glory

Fall 1939

The sun was low in the sky, filtering through the banyan trees as my father walked me down the uneven sidewalks of my youth. The single-storied stucco houses we passed stood snugly on their lots, painted from a palette of pale colors. Green hoses lay in brown yards like snakes uncoiling to sun themselves. At their heads, sprinklers sprayed giggly kids chased by yappy dogs.

This was our neighborhood. Northwest 4th Street, Miami. A mile or so from the Tower.

The Tower Theater was where I went if I wanted to go to other neighborhoods, ones that were years away, like the Old West (if Stagecoach was showing), or light-years away (if it was a Buck Rogers serial). Who knew what adventures awaited me at the Tower? Would Beau Geste be off to fight in the French Foreign Legion? Would Mr. Smith go to Washington or Dorothy to Oz?

As we rounded the corner, taking a right on 17th, my father reached for my hand and placed it into the strength of his. At five foot eleven he was thin as a rail but just as strong, tempered by years of carrying bulky cash registers from busi- nesses to his car, from his car into our house, then back again. Repair work was slow for the decade of the Great Depression, never steady, never certain.

But because he was often out of work, we were together a lot; this was not the case with my mom, who worked as a beautician, leaving me few leisurely days with her like the one I had today with my dad.

We turned left on 8th, my anticipation quickening with our pace. There on the right it stood—the Tower Theater, with its sleek, art-deco architecture, its forty-foot tower, its glittering marquee:

Code of The Secret Service

Starring Ronald Reagan and Rosella Towne

My father dug into his pocket, mincing out change. “One adult, one child,” he said, and with that, we were in. A ticket taker opened the door that led into the cool lobby and then into the cavernous dark of the theater. We had missed the newsreels, but we were just in time for the feature presentation. We settled into our cushioned seats.

A cone of light flickered from the projection room onto the screen. This time the “neighborhood” was Washington, DC. This time the buildings were not stucco but marble.

The Capitol. The Washington Monument. The Lincoln Memorial. They all loomed on the screen, and my nine-year- old imagination took off.

The camera cut to words on an office door—“Secret Service Division.” Through that door bounded the dashing, clean-cut Brass Bancroft, a Secret Service agent played by the young, athletic Ronald Reagan. He flashed an all-American smile as his supervisor talked about a counterfeiting ring the Service had been tracking. He needed a stakeout south of the border. He assigned Brass to go undercover and check it out. It would be dangerous, but duty called.

The next minute Brass was on a plane that we saw dotting across a map of the United States, then landing in Mexico. Brass picked his way through uncertain streets and more uncertain alleys, into a shady-dealing casino, then a shadowy bar, and then a fight broke out. A flurry of fists. Bodies flying through the air, crashing onto tables.

I gripped my father’s arm on the armrest.

It was one cliff-hanging moment after another. One narrow escape after another. One plot twist after another. Until at last a beautiful girl, unimpressed by Brass, entered the story. The two were soon captured by the counterfeiters, and the girl was now even less impressed with Brass than she had been.

Before I knew it, the tables had turned. Brass had slipped out of the ropes that tied him to the chair, rescuing the girl and routing the counterfeiters. Suddenly the special agent had the girl’s admiration and her affection. The music swelled, the credits rolled, and the tail end of the reel threaded through the projector. A splash of white rinsed the screen, followed by the houselights.

When we left the theater, it was dark. My father asked if I liked the movie, and I said I did. With the marquee lights behind us and the streetlights ahead of us, we made our way home. He pulled out a small bottle of whiskey and took a swig, then another before pocketing it.

My father was not Brass Bancroft, not by a long shot. But I loved him. He was kind and good, at least to me. The Depression had taken away his dignity, his confidence, his manhood. But in return, it had given him to me.

I leaned into him while we walked, tired and hungry and quiet.

“How about a lift?” he asked. I nodded. He hefted me onto his shoulders, crossing his arms over my legs so I wouldn’t fall off. I took in a chestful of the heavy night air, mingled with the smell of his skin, his hair, his breath.

There was no place in the world I felt more secure, and no place in the world I would rather be.

We walked past neighbors’ houses and the suppertime smells that drifted out their open windows. By the time we were home, I was almost asleep.

Yet something was waking in me, drawing me. Was it the selfless service of the agent to his country? Was it the danger? The intrigue? The foreign travel?

Or was it the girl?

Chapter 1

Just Another Day at the Office

I have a rendezvous with Death At some disputed barricade. . . . And I to my pledged word am true, I shall not fail that rendezvous.

Alan Seeger , “I Have a Rendezvous with Death”

March 30, 1981

It had been almost forty-two years since I saw that B movie at the Tower Theater, and I was a Secret Service agent assigned to protect the actor in that movie, who was now playing the role of a lifetime: the president of the United States. For the past eighteen years I’d worked my way through the ranks in the Service—investigating stolen checks, standing post, working shifts, doing advances—and now I was lead agent for the special detail that protected the president.

When I was younger, I was fascinated by the poem “I Have a Rendezvous with Death,” by Alan Seeger. I had even memorized it decades ago and have returned to it often. The poem makes the encounter with Death seem as calm and natural as watching the trees return to life, “when Spring comes back with rustling shade and apple-blossoms fill the air.”

Death is talked about not in cold, impersonal descrip- tions but in warm terms such as “rendezvous” and in personal images of Death taking the poet’s hand. For the poet, death is not an encounter to be feared but an appointment to be kept. God is in it. Hope is in it. And so is courage.

There was another man enchanted by this poem. When John F. Kennedy returned from his honeymoon in October 1953, he read “I Have a Rendezvous with Death” to his young wife, Jacqueline, telling her it was his favorite poem. After that, she memorized the poem, often reciting it to him privately. Her soft voice and unhurried accent seemed to calm him, giving him the resolve he needed to face the future he felt awaited him.

In 1963, Jacqueline taught the poem to Caroline, their five-year-old daughter. On October 5, 1963, when the now President Kennedy was meeting with his National Security Council in the Rose Garden, his young daughter slipped into the meeting and sidled next to him. She tugged at him to get him to notice her. The president dismissed her, but in a way only a young daughter can, she kept trying to get his attention. The president turned to her, smiling. Caroline looked into his eyes and recited the poem. She recited it flawlessly, with perfect diction. When she finished, no one spoke. It seemed not simply a sweet moment but a sacred one. A sense of reverence permeated the silence, touching everyone.

Seven weeks later, this little girl’s father made his rendezvous with Death at the disputed barricade of Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. A day that has haunted the memory of every American. And every Secret Service agent.

Now, almost eighteen years after that rendezvous, I was an agent, tasked with protecting the president. I was part of the barricade between him and Death. And my sole purpose was to make sure this was the one appointment he would not keep.

March 30, 1981, started for me in the predawn chill, where I jogged around our neighborhood in North Potomac, Maryland. A small, sequestered suburb northwest of DC, it had been carved out of a forest near the Potomac River. The subdivisions had bucolic names like Travilah Meadows, Quail Run, and Mills Farm, and they lived up to their names, forming a quiet respite from the bustling streets of the nation’s capital.

It was a spring day, not blue and fair but gray and overcast as I drove into DC. And although the first meadow flowers had appeared in some well-manicured parts of the city, the more than three thousand cherry trees there had not yet blossomed to fill the air with their delicate scent.

The first thing I did when I arrived for work that morning was to sign in for target practice at the gun range in the basement of the old post office building. I was dressed for work in a plain, blue-gray, blend-in-with-the-crowd suit and tie, my gun holstered beneath my unbuttoned coat. As I faced downrange, I spread my feet to square with my shoulders. I relaxed my arms, shaking my hands at my sides to loosen them.

As an agent, I’d had it drilled into me that the one thing I could never do was freeze. In a crisis, an agent doesn’t have time to think. Reactions need to be instinctive. So much as a blink or a balk, and I would be a dead man. Or worse—the president would be a dead man.

With a sudden, jarring sound, the target turned from being a thin piece of paper to a man with a pistol. Immediately I flipped open my coat with my right hand, grabbed the butt of my gun with my left, and fired two shots that drilled the paper assassin.

My gun was a stubby Smith & Wesson Model 19, with a six-round chamber that could be changed out in three to four seconds. The impact on the hand was brutal, but the impact on the target was even more so. The .38-caliber bullets burst from the two-and-a-half-inch barrel at a speed of 1,110 feet per second. If the bullet didn’t kill you, the blow from the bullet would knock you off balance—if not off your feet. With the Service using hollow points, though, if the bullet did hit you, it would likely be lethal.

When you are protecting the most important leader in the world, lethal is what you want. You don’t want to give an assassin a chance to shoot once, let alone a second chance. You want to drop him the way I dropped that target in the shooting range.

After cleaning my gun, I left for “the office.” The office for me was known as W-16, located in the bowels of the White House, directly under the Oval Office. It was the Secret Service’s command center, the central nervous system for protecting the president and other key leaders and their families. Intelligence was routed to us there—field reports, surveillance feeds, wiretaps—up-to-date intel on people who were known threats. The Service receives threats every day on the lives of those they are assigned to protect—especially on the life of the president. The lower his approval rating is, the higher the number of threats. And since taking office, President Reagan’s approval rating had plummeted.

The president had been in office just seventy days. For the first week after his inauguration, every time the president left the safety of the White House, I stuck so close I could smell his aftershave. But for the next seven weeks after that, others in the management team had been with him while I attended the Federal Executive Institute. Now back at the White House, I felt today would be a good day to spend time with him and get to know him. Although an agent never wants to get on too-friendly terms with the president, you do want to be able to do the best job of protecting him, and that involves knowing him. Knowing how fast he walks or how slow. Knowing how often he stops along a rope line to greet the public and for how long. Knowing whether he is cautious or cavalier. Is he immediately compliant to an agent’ssuggestions, is he momentarily hesitant, or is he resistant to the point that the agent has to persuade him? In scenarios where every second counts, knowledge like this can be lifesaving.

Johnny Guy was the agent assigned to travel with the president to the Washington Hilton that afternoon, where he was to give a short speech to a labor union within the AFL- CIO. I talked to Guy sometime after ten in the morning to ask if I could take his place. He agreed.

I called my wife, Carolyn, at her office to tell her that I would be accompanying the president to the Hilton and that if she wanted to see him, his motorcade would be across the street. She was a trial lawyer for the IRS at the time, and she had a fourth-floor office in the Universal North Building, with a window that looked down on T Street. She was glad I called and eager to see the president, if only for a moment.

It was a routine route for a routine stop for a routine speech. But that’s the rub: routine is the enemy of every agent. With routine comes boredom. With boredom comes distraction and letting down your guard. When that hap- pens, people die.

We had taken presidents and vice presidents to the Washington Hilton 110 times since 1972, and nobody had died. Nobody had even come close. An advance search of the hotel had been done, along with the strategic assignment of agents, sixty-six for this event, plus police. Had we been scheduled for an out-of-Washington trip—say, in Baltimore—we would have used twice that number.

Paul Mobley and Mary Ann Gordon headed up transportation. Both had done the route to the Hilton before, as well as numerous runs to the hospital. They had put the motorcade in place—a caravan of vehicles, each with different duties assigned to those riding in them. There was a lead car that set the pace at twenty-five miles per hour, which would stop for nothing unless it hit someone. There was a tail car, a van with eight agents, and a pilot car, all looking for suspicious vehicles along the route. There were a few ancillary cars, like a spare car with protective support and technicians, a communications car, and a staff car. There was the control car, which would include Deputy Chief of Staff Mike Deaver. Finally, there was the president’s limousine, which was code-named Stagecoach. Every inch of it was bulletproof, covered in level-4 armor. It weighed six and a half tons and stretched nearly twenty-two feet. There was even an “emergency motorcade” of four vehicles parked at the hotel, should a quick escape be needed. All total, fifteen vehicles.

We had plotted a protected route with police officers assigned to block off intersections along the way. The plan was to arrive at the VIP entrance; otherwise we would have to go to the hotel’s basement, where we would have some twelve hundred cars to check out. Then, when the motorcade stopped at the entrance, where uniformed police formed a perimeter of protection, the car doors would open with strategic synchronization, and the president would be whisked away to the hotel ballroom.

It was all very regimented. And all very routine.

In spite of how well rehearsed our responsibilities were, the risks were real. You know that danger is out there—real danger—you just don’t know where. Absence of evidence doesn’t mean evidence of absence. Just because there is no sign of a threat doesn’t mean there isn’t one. The problem isn’t what you know; it’s what you don’t know. Not what you see or hear, but what you don’t see, don’t hear. It’s the open window you don’t notice. Or the sound from a book depository that takes you a second too long to recognize as a gunshot.

Not only do you have to be vigilant; you have to be hypervigilant.

Ever since I joined the agency in 1962, a number of people had died. President Kennedy had been assassinated. Attorney General Robert Kennedy had been assassinated. Governor George Wallace survived an assassination attempt but was paralyzed. President Ford had escaped two attempts on his life. And civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated.

President Kennedy, Wallace, and Ford had been under the protection of the Secret Service. The others were not. In some cases, agents were negligent. In others, they were vigilant. In all cases, life or death was determined by seconds. Sometimes split seconds.

I had assigned Bill Green to work the advance on the presi- dent’s trip to the Hilton, which he started on March 25. His job was to draw up a security plan that pinpointed where each agent was to be stationed in and around the hotel. He was to make sure a background check was done on everyone scheduled to meet with the president during his visit, however briefly. He was also responsible for inspecting the ballroom, the hotel basement, the holding room, the stairwells, the elevators, and the VIP entrance.

Though it was the first time Bill had done this at the Hilton, his preparations were thorough, down to the smallest detail. He visited the hotel on Friday for another inspection, then again on Saturday. On Sunday he made a few final calls before finishing his security report, which he handed in first thing on Monday, March 30. He checked the latest intel, and he was told that there was nothing on the radar in terms of threats to the president’s appearance that day.

The trip to the Hilton was so routine that I decided bullet- proof vests weren’t necessary. Besides, it was a muggy day, with rain, and vests were hot and uncomfortable. I sat in the front passenger seat; the president sat behind me. We drove down Connecticut Avenue, got on 18th Street, and made a left onto T Street, which took us to the hotel. When we stopped at the designated entrance, police and other agents were waiting for us. I got out of the car first to pull the coded switch on the president’s door—a tricky thing because if you don’t do it just right, the system has to be rebooted before you can open the door.

President Reagan, a probusiness Republican, was at odds with the largely Democratic labor unions. But he had been invited to speak and felt a sense of responsibility to come. When Reagan had worked as an actor in Hollywood, he served as president of the Screen Actors Guild, a union under the auspices of the very group to which he was scheduled to speak. And so he felt a certain kinship with the audience.

Once inside, I ushered the president into the elevator that led to the permanent holding room. As we ascended the platform, I picked another agent to stand near the president so I could sit behind him to survey the room. I had a good eye, trained to see trembling hands, darting eyes, sweat on the forehead . . . a disturbed look on the face . . . clothes or shoes that didn’t fit in . . . a bulge in an overcoat . . . a purse clutched a little too tightly.

After Reagan was introduced, he stood behind the armored podium to speak. But I wasn’t paying attention to the speech; I was paying attention to the crowd, looking with eyes that could cut steel they were so intense. An agent’s eyes are weapons, every bit as intimidating as a semiautomatic. I sat with a face as cold and hard as if it had been cut from Mount Rushmore and scanned the ballroom, searching for a face that was every bit as cold and hard as mine, for eyes every bit as intense.

One of the things agents are looking for is a gun. We are trained to shout whenever we see one—“Gun right” if an agent sees someone with a gun to the right or “Gun left” or “Gun in front.” Depending on the type of threat and where the threat is, I might push the president down behind the podium, cover him with my body on the stage, or evacuate him from the stage.

When President Reagan finished speaking, the audience rose to applaud. But the speech wasn’t his best, and the gesture was more respectful than enthusiastic. With agents flanking his sides, the president stopped to shake a few hands, then we escorted him to the elevator.

In the meantime, Carolyn had lost track of time. She had received a call at 1:45 and became so engrossed that she forgot all about seeing the president. When she suddenly realized what time it was, she looked out the window, and the motorcade was still parked across the street. Even though it was rainy, she grabbed her purse and rushed downstairs to the sidewalk, shortly before the president emerged from the Hilton.

When the VIP elevator at the Hilton opened, the other agents and I surrounded the president in a human barricade we called the “diamond formation.” The diamond had four points. Tim McCarthy was positioned in front, Eric Littlejohn in the rear. Jim Varey was stationed at the right, Dale McIntosh at the left. Ray Shaddick and I were inside the diamond on either side of the president. Shaddick was in “POTUS Left” position, I was “POTUS Right,” eighteen inches behind the president. Shaddick carried a bulletproof steel slab to protect the president in case of an attack, coated with leather so as not to appear foreboding. Bringing up the rear was Bob Wanko, the gunman with an Uzi in a briefcase, again so as not to appear foreboding.

As we opened the door to the outside, uniformed police in raincoats stood guard on the sidewalk that was wet from an earlier shower. Beyond them was the rope line, where a gaggle of around thirty onlookers and members of the press eagerly awaited an opportunity to shout out a greeting or a question. All my senses were keenly alert, scanning the sur- roundings for any possible threat—any person that seemed out of place or out of sorts, any door that might be ajar, any window that might be open, any sudden movement, any startling sound. All the while, I was plotting an ever- changing escape route if something did happen. If a threat presented itself as we walked out the door, I would pull the president into the building; if we were closer to the limousine, I would push him into the car.

Carolyn was across the street, standing on the fringe of a small crowd that had gathered there, craning her neck to catch a glimpse of the new president.

As the president approached the limousine, McCarthy got the door, which opened toward the crowd. The president raised his right arm and waved to the small line of spectators that had gathered on T Street. A woman on the rope line called out, “Mr. President! President Reagan!” The president paused a second—only a second—turning his head to the left to acknowledge her, raising his left hand, and mouthing what seemed to be the word hi.

In that moment, I moved instinctively to the president’s left side to strengthen the barricade between him and the crowd.

In the Secret Service: The True Story of the Man Who Saved President Reagan's Life

- Genres: History, Nonfiction

- hardcover: 336 pages

- Publisher: Tyndale House Publishers

- ISBN-10: 1414387482

- ISBN-13: 9781414387482