Excerpt

Excerpt

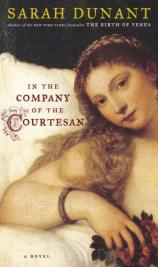

In the Company of the Courtesan

chapter one

Rome, 1527

My lady, Fiammetta Bianchini, was plucking her eyebrows and biting

color into her lips when the unthinkable happened and the Holy

Roman emperor’s army blew a hole in the wall of God's eternal

city, letting in a flood of half-starved, half-crazed troops bent

on pillage and punishment.

Italy was a living chessboard for the ambitions of half of Europe

in those days. The threat of war was as regular as the harvest,

alliances made in winter were broken by spring, and there were

places where women bore another child by a different invading

father every other year. In the great and glorious city of Rome, we

had grown soft living under God's protection, but such was the

instability of the times that even the holiest of fathers made

unholy alliances, and a pope with Medici blood in his veins was

always more prone to politics than to prayer.

In the last few days before the horror struck, Rome still couldn't

bring herself to believe that her destruction was nigh. Rumors

crept like bad smells through the streets. The stonemasons shoring

up the city walls told of a mighty army of Spaniards, their

savagery honed on the barbarians of the New World, swelled with

cohorts of German Lutherans fueled on the juices of the nuns they

had raped on their journey south. Yet when the Roman defense led by

the nobleman Renzo de Ceri marched through the town touting for

volunteers for the barricades, these same bloodthirsty giants

became half-dead men marching on their knees, their assholes close

to the ground to dispel all the rotting food and bad wine they had

guzzled on the way. In this version, the enemy was so pathetic

that,\ even were the soldiers to find the strength to lift their

guns, they had no artillery to help them, and with enough stalwart

Romans on the battlements, we could drown them in our piss and

mockery as they tried to scale their way upward. The joys of war

always talk better than they play; still, the prospect of a battle

won by urine and bravura was enticing enough to attract a few

adventurers with nothing to lose, including our stable boy, who

left the next afternoon.

Two days later, the army arrived at the gates and my lady sent me

to get him back.

On the evening streets, our louche, loud city had closed up like a

clam. Those with enough money had already bought their own private

armies, leaving the rest to make do with locked doors and badly

boarded windows. While my gait is small and bandied, I have always

had a homing pigeon's sense of direction, and for all its twists

and turns, Rome had long been mapped inside my head. My lady

entertained a client once, a merchant captain who mistook my

deformity for a sign of God's special grace and who promised me a

fortune if I could find him a way to the Indies across the open

sea. But I was born with a recurring nightmare of a great bird

picking me up in its claws and dropping me into an empty ocean, and

for that, and other reasons, I have always been afraid of

water.

As the walls came into sight, I could see neither lookouts nor

sentries. Until now we had never had need of such things, our

rambling fortifications being more for the delight of antiquarians

than for generals. I clambered up by way of one of the side towers,

my thighs thrumming from the deep tread of the steps, and stood for

a moment catching my breath. Along the stone corridor of the

battlement, two figures were slouched down against the wall. Above

me, above them, I could make out a low wave of moaning, like the

murmur of a congregation at litany in church. In that moment my

need to know became greater than my terror of finding out, and I

hauled myself up over uneven and broken stones as best I could

until I had a glimpse above the top.

Below me, as far as the eye could see, a great plain of darkness

stretched out, spiked by hundreds of flickering candles. The

moaning rolled like a slow wind through the night, the sound of an

army joined in prayer or talking to itself in its sleep. Until then

I think even I had colluded in the myth of our invincibility. Now I

knew how the Trojans must have felt as they looked down from their

walls and saw the Greeks camped before them, the promise of revenge

glinting off their polished shields in the moonlight. Fear spiked

my gut as I scrambled back down onto the battlement, and in a fury

I went to kick the sleeping sentries awake. Close to, their hoods

became cowls, and I made out two young monks, barely old enough to

tie their own tassels, their faces pasty and drawn. I drew myself

to my full height and squared up to the first, pushing my face into

his. He opened his eyes and yelled, thinking that the enemy had

sent a fatheaded, smiling devil out of Hell for him early. His

panic roused his companion. I put my fingers to my lips and grinned

again. This time they both squealed. I've had my fair share of

pleasure from scaring clerics, but at that moment I wished that

they had more courage to resist me. A hungry Lutheran would have

had them split on his bayonet before they might say Dominus

vobiscum. They crossed themselves frantically and, when I

questioned them, waved me on toward the gate at San Spirito, where,

they said, the defense was stronger. The only strategy I have

perfected in life is one to keep my belly full, but even I knew

that San Spirito was where the city was at its most vulnerable,

with Cardinal Armellini's vineyards reaching to the battlements and

a farmhouse built up and into the very stones of the wall

itself.

Our army, such as it was when I found it, was huddled in clumps

around the building. A couple of makeshift sentries tried to stop

me, but I told them I was there to join the fight, and they laughed

so hard they let me through, one of them aiding me along with a

kick that missed my rear by a mile. In the camp, half the men were

stupid with terror, the other half stupid with drink. I never did

find the stable boy, but what I saw instead convinced me that a

single breach here and Rome would open up as easily as a wife's

legs to her handsome neighbor.

Back home, I found my mistress awake in her bedroom, and I told her

all I had seen. She listened carefully, as she always did. We

talked for a while, and then, as the night folded around us, we

fell silent, our minds slipping away from our present life, filled

with the warmth of wealth and security, toward the horrors of a

future that we could barely imagine.

By the time the attack came, at first light, we were already at

work. I had roused the servants before dawn, and my lady had

instructed them to lay the great table in the gold room, giving

orders to the cook to slaughter the fattest of the pigs and start

preparing a banquet the likes of which were usually reserved for

cardinals or bankers. While there were mutterings of dissent, such

was her authority—or possibly their desperation& --- that

any plan seemed comforting at the moment, even one that appeared to

make no sense.

The house had already been stripped of its more ostentatious

wealth: the great agate vases, the silver plates, the majolica

dishes, the gilded crystal Murano drinking glasses, and the best

linens had all been stowed away three or four days before, wrapped

first inside the embroidered silk hangings, then the heavy Flemish

tapestries, and packed into two chests. The smaller one was so

ornate with gilt and wood marquetry that it had to be covered again

with burlap to save it from the damp. It had taken the cook, the

stable boy, and both of the twins to drag the chests into the yard,

where a great hole had been dug under the flagstones close to the

servants' latrines. When they were buried and covered with a

blanket of fresh feces (fear is an excellent loosener of the

bowels), we let out the five pigs, bought at a greatly inflated

price a few days earlier, and they rolled and kicked their way

around, grunting their delight as only pigs can do in shit.

With all trace of the valuables gone, my lady had taken her great

necklace& --- the one she had worn to the party at the Strozzi

house, where the rooms had been lit by skeletons with candles in

their ribs and the wine, many swore afterward, had been as rich and

thick as blood& --- and to every servant she had given two fat

pearls. The remaining ones she told them were theirs for the

dividing if the chests were found unopened when the worst was over.

Loyalty is a commodity that grows more expensive when times get

bloody, and as an employer Fiammetta Bianchini was as much loved as

she was feared, and in this way she cleverly pitted each man as

much against himself as against her. As to where she had hidden the

rest of her jewelry, well, that she did not reveal.

What remained after this was done was a modest house of modest

wealth with a smattering of ornaments, two lutes, a pious Madonna

in the bedroom, and a wood panel of fleshy nymphs in the salon,

decoration sufficient to the fact of her dubious profession but

without the stench of excess many of our neighbors' palazzi

emitted. Indeed, a few hours later, as a great cry went up and the

church bells began to chime, each one coming fast on the other,

telling us that our defenses had been penetrated, the only aroma

from our house was that of slow-roasting pig, growing succulent in

its own juices.

Those who lived to tell the tale spoke with a kind of awe of that

first breach of the walls; of how, as the fighting got fiercer with

the day, a fog had crept up from the marshes behind the enemy

lines, thick and gloomy as broth, enveloping the massing attackers

below so that our defense force couldn't fire down on them

accurately until, like an army of ghosts roaring out of the mist,

they were already upon us. After that, whatever courage we might

have found was no match for the numbers they could launch. To

lessen our shame, we did take one prize off them, when a shot from

an arquebus blew a hole the size of the Eucharist in the chest of

their leader, the great Charles de Bourbon. Later, the goldsmith

Benvenuto Cellini boasted to anyone who would listen of his

miraculous aim. But then, Cellini boasted of everything. To hear

him speak& --- as he never stopped doing, from the houses of

nobles to the taverns in the slums& --- you would have thought

the defense of the city was down to him alone. In which case it is

him we should blame, for with no leader, the enemy now had nothing

to stop their madness. From that first opening, they flowed up and

over into the city like a great wave of cockroaches. Had the

bridges across the Tiber been destroyed, as the head of the defense

force, de Ceri, had advised, we might have trapped them in the

Trastevere and held them off for long enough to regroup into some

kind of fighting force. But Rome had chosen comfort over common

sense, and with the Ponte Sisto taken early, there was nothing to

stop them.

And thus, on the sixth day of the month of May in the year of our

Lord 1527, did the second sack of Rome begin.

What couldn't be ransomed or carried was slaughtered or destroyed.

It is commonly said now that it was the Lutheran lansquenets troops

who did the worst. While the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, might

be God's sworn defender, he wasn't above using the swords of

heretics to swell his army and terrify his enemies. For them Rome

was sweet pickings, the very home of the Antichrist, and as

mercenaries whom the emperor had conveniently forgotten to pay,

they were as much in a frenzy to line their pockets as they were to

shine their souls. Every church was a cesspool of corruption, every

nunnery the repository for whores of Christ, every orphan skewered

on a bayonet (their bodies too small to waste their shot on) a soul

saved from heresy. But while all that may be true, I should say

that I also heard as many Spanish as German oaths mixed in with the

screaming, and I wager that when the carts and the mules finally

rode out of Rome, laden with gold plate and tapestries, as much of

it was heading for Spain as for Germany.

Had they moved faster and stolen less in that first attack, they

might have captured the greatest prize of all: the Holy Father

himself. But by the time they reached the Vatican palace, Pope

Clement VII had lifted up his skirts (to find, no doubt, a brace of

cardinals squeezed beneath his fat stomach) and, along with a dozen

sacks hastily stuffed with jewels and holy relics, run as if he had

the Devil on his heels to the Castel Sant'Angelo, the drawbridge

rising up after him with the invaders in sight and a dozen priests

and courtiers still hanging from its chains, until they had to

shake them off and watch them drown in the moat below.

With death so close, those still living fell into a panic over the

state of their souls. Some clerics, seeing the hour of their own

judgment before them, gave confessions and indulgences for free,

but there were others who made small fortunes selling forgiveness

at exorbitant rates. Perhaps God was watching as they worked:

certainly when the Lutherans found them, huddled like rats in the

darkest corners of the churches, their bulging robes clutched

around them, the wrath visited upon them was all the more

righteous, as they were disemboweled, first for their wealth and

then for their guts.

Meanwhile, in our house, as the clamor of violence grew in the

distance, we were busy polishing the forks and wiping clean the

second-best glasses. In her bedroom, my lady, who had been

scrupulous as ever in the business of her beauty, put the finishing

touches to her toilette, and came downstairs. The view from her

bedroom window now showed the occasional figure skidding and

hurtling through the streets, his head twisting backward as he ran,

as if fearful of the wave that was to overwhelm him. It would not

be long before the screams got close enough for us to distinguish

individual agonies. It was time to rally our own defense

force.

Excerpted from IN THE COMPANY OF THE COURTESAN © Copyright

2011 by Sarah Dunant. Reprinted with permission by Random House, a

division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

In the Company of the Courtesan

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 384 pages

- Publisher: Random House

- ISBN-10: 1400063817

- ISBN-13: 9781400063819