Excerpt

Excerpt

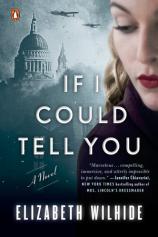

If I Could Tell You

London, 1944

People fell from the sky. Some spread-eagled, some twisting and flailing, others drifting down as if weightless. Face after face after face passed her by, neared then disappeared into greyness. They were angels, falling from the angel roof. She understood she was to join them. They were men and women and children. They were war dead. She understood she was war dead too and reached out her hands. Death is truth, they told her, falling. Her mouth was caked in dust. Her throat was dust. Dust was in her nose. She took a breath and it was ashes.

She coughed and there were knives in her chest. She couldn’t move her arms, her hands, her legs, her feet. She could move her head a little. She tried to call out but her voice was shut up in her throat. Someone else called. She heard their thin cries. It was dark.

Her mother told her she needed a little colour at her neck. Her mother told her that if she’d had her opportunities when she was a girl she wouldn’t have thrown them away. ‘Half a pound of antimacassars,’ said her mother. She was pinned. She couldn’t move her hands, her arms, her legs. Dust silted her mouth and choked her. It was sunny and hot. The tide was out. She was walking down a shingle beach with a mermaid’s purse in the pocket of her dress. The sea was sparkling. Something shifted, tilted, gave way. A cavity opened up, a vacancy. From above came a narrow probing beam of light. Someone groaned; something moved. She smelled gas. The light went out. She was walking down a shingle beach with a mermaid’s purse in her pocket. Protect my family.

1939

Julia Compton was frightened, of course she was. The gas masks dangling from the hallstand in their cardboard cartons – hers, her husband’s, her son’s and their housekeeper’s – lurched her stomach every time she laid eyes on them. Obscene things, rubbery and goggle-eyed. She couldn’t remember much about the previous war – she’d been too young – only the maroons banging and bursting at the end of it. That did not stop her from imagining a miasma of yellow mustard gas creeping over the town, borne inland on sea breezes, settling into the furrows of ploughed fields.

That summer they all knew it was coming. The papers were full of it, the pubs and pulpits too. Appeasement had failed. Any day now the waiting would be over. Twenty years, and they’d scarcely got over the last one, people were saying. For this reason she was as relieved as everyone else when a film crew arrived from London in the last week of August and gave them all something different to talk about.

The great topic of conversation was why they had come. It was a small town on an east-coast estuary with nothing noteworthy about it. Trippers passed it by routinely; amateur painters tired of hunting for subjects and didn’t stay long. What could possibly interest them? Fishing, it turned out.

The news was received with surprise. You caught fish, you smoked them, you sold them. No one in their right mind filmed them. Somewhat later the penny dropped. Films about fishing must feature those who made their living that way. Women were the first to realize this and the hairdresser on the high street found herself busy.

‘What is it,’ said Julia, ‘that so attracts people to filming? Is it glamour, do you think?’ The six o’clock bulletin was over – no war yet – and they’d switched off the wireless. A pleated paper fan hid the summer hearth. On the mantelshelf: a green ceramic bowl of spills for the fires they would have to light soon, a brass carriage clock, an engraved invitation on stiff white card to a yacht-club dance propped against well-dusted ornaments.

Richard looked up from the newspaper and lamplight glanced off his face. These days she often forgot how handsome her husband was – it was the same as the mantelshelf ornaments, familiarity cloaking their original appeal – but on this occasion it struck her as if she were seeing it for the very first time, as if he were a rare prize displayed in a shop window alongside bric-a-brac. He was nearing forty, eight years older than her, and age, which would eventually dim and blur her slight, dark prettiness, was only maturing his good looks, confirming them with a few crow’s feet and a distinguished scattering of grey.

Beauty was unfair that way: it treated men and women differently. ‘The matinee idol’, her mother had called him. He was a solicitor and oddly lacking in vanity. She set down her sherry glass on a leather-topped coaster.

'Peter’s been down at the quayside all afternoon watching them, along with half the town.’ Their son Peter was nine. ‘In his case, I suspect it’s the mechanics of it.’

‘The train-set aspect?’

‘You have to admit it’s rather impressive kit they’ve got.’ She laughed.

‘You’re just as bad as he is.’ He put the newspaper to one side. ‘I think I might have secured a counsel for Perry Clayton.’

Two months ago Perry Clayton, who worked in the smokehouse on Brewer Street, had got into a brawl with a man who was sleeping with his wife and beaten him so badly he later died of his injuries. He was currently on remand awaiting trial at the assizes.

'That’s good,’ said Julia. Harry, their housekeeper, came in to announce dinner was ready. Peter’s footsteps pounded down the stairs as they went into the hallway.

‘Walk, don’t run,’ Richard said to him. ‘How many times have I told you? Don’t they teach you that at school?’ By the time they sat down at the table, . A phrase occurred to her: ‘the institution of marriage.'

She slipped her napkin out of its bone ring. Julia tidied up the clothes her son had left on the floor. ‘Have you brushed your teeth?’

‘Yes, Madre,’ said Peter. He was in his pyjamas, pushing his Hornby engine to and fro with a bare foot.

‘Pop into bed then and I’ll read to you.’ Peter bounced on the mattress and flopped back.

‘Mr Birdsall let me look through the camera.’ Julia closed a drawer.

‘Who’s Mr Birdsall?’ ‘He’s in charge of the filming,’ said Peter. ‘People who are in charge of films are called directors.’

‘Are they,’ said Julia. ‘I hope you weren’t making a nuisance of yourself.’

‘Filming’s ever so complicated,’ said Peter. ‘Like maths.’ Peter was good at maths.

‘Get yourself under the covers now.’

She sat down on the edge of the bed and opened the book. The Story of the Treasure Seekers. ‘Are you sure you want this one again?’ He nodded. ‘Being the adventures of the Bastable children in search of a fortune,’ it said on the title page.

Underneath was her name in an eight-year old’s loopy letters. Peter never seemed to tire of it. Perhaps as an only child he enjoyed imagining himself part of a large family.

When he settled himself down she began to read. ‘“It is one of us that tells this story – but I shall not tell you which: only at the very end perhaps I will. While the story is going on you may be trying to guess, only I bet you don’t. It was Oswald who first thought of looking for treasure. Oswald often thinks of very interesting things –”’ A satisfied chuckle from the pillow.

‘He gives the game away. Right there.’

‘He does, doesn’t he,’ said Julia, turning a page.

This part of the day belonged to her alone and she took full pleasure from it. One chapter a night was the rule but the chapters were short and she allowed herself to be talked into a second. By the end of it his breathing was even and he had stopped interrupting. Sleepiness turned the clock back a little – sometimes by as much as a year, which was when he had last willingly submitted to a goodnight kiss. Tonight he must have been especially tired because he reached up and hugged her with his thin, reedy arms, which allowed her to drink in his smell under the cursory face-wash. To be hugged by your child, was anything better than that? Or more bittersweet? For with a hug came a whole history of hugs and the reasons for hugs, along with a future when they would eventually dwindle to handshakes and pecks on the cheek. Another week and he would be back at school. Her spirits sank.

All mothers whose children have been sent away to board learn to endure the highs and lows, to post their anxious love in letters and parcels, to measure out the year in half-terms and holidays. Perhaps if they had been able to have more children she wouldn’t have missed him quite so much when he was away.

‘You won’t die like the mother in the book, will you?’ said Peter. Julia knew better than to be worried by this. He was not morbid or anxious, only in search of rote reassurance. The question tended to come up at this early point in the story, before the motherless Bastables began their adventures.

‘I’m not planning on it,’ she said, stroking his hair, dark like hers.

‘Not until you’re a hundred.’

‘At least.’ She switched off the light.

It had been a beautiful summer. Stand in the garden, stare up at the cloudless sky and you would think nothing could be wrong anywhere in the world. The next morning sun was streaming through the windows again. The house was quiet. Richard had gone to work and Peter had dashed off somewhere after breakfast. Julia was not about to interfere with the way he spent his time or tie him to her apron strings – that was bad mothering in her opinion – but still the hours to his departure counted down in her head with the same dread tick as the country’s approach to war.

The Broadwood lived in the drawing room where the wireless was. After instructing Harry on the day’s tasks and chores – or ‘conferring’, as she preferred to think of it – Julia selected a score from the sheet music in the canterbury and sat down to play. ‘La Cathédrale engloutie’. It had to be said it wasn’t one of Richard’s favourites. He was more of a Bach man.

Debussy was deceptive. The refusal of the harmonies to resolve, the blurred, sonorous bass notes, the layers of voices, masked precision, each sound occupying its own rightful place. The piece demanded technique, control. Within a chord it was often necessary to play one note more strongly than the others to bring out the meaning, and the pedalling had to be exact, never forced.

‘The art of pedalling is a kind of breathing,’ so Debussy had said, and her tutor had often quoted. Then and only then you saw the scenes hidden in the music, heard the bells of the drowned cathedral ringing under the water, an elegy for lost faith or a testament to faith’s survival; she was never sure. When she reached the tolling end she began all over again, the watery notes sliding under her fingers.

‘Mrs C? Mrs C?’ Lost in music, Julia raised her head. Harry was in the doorway, smudges on her apron, thick stockings rolled down over garters. The old blind dog bumbled after her, banging into things. Today he was wearing a dressing on his head: this was the housekeeper’s doing and would soon be banged off.

‘You’re wanted on the telephone.’ Like many women of her generation, Harry regarded a ringing telephone in the same grave light as a telegram, and this was reflected in her tone. (Harry’s preferred form of communication was on the astral plane; she was a spiritualist.)

‘Oh, sorry, I didn’t hear.’ ‘It’s Mrs Spencer.’ Julia went out into the hall, with its wallpaper of tawny leaves and beeswaxed banister. Of all their circle of acquaintance, Fiona Spencer was the one she counted as a true friend, without entirely approving of her, it had to be said.

Four years ago her husband had dropped dead one Sunday afternoon while washing his Wolseley. Since then she had taken on the draper’s shop in town; a rather surprising step for someone of her class, means and background was the local opinion. Then there were the rumours of Geoffrey’s philandering, which seemed to indicate some failing on her part, either in provoking the infidelities or in putting up with them. To which must be added the mildly notorious behaviour of her children, that of the elder daughter, Ginny, in particular.

All the same, Julia couldn’t resist Fiona’s vitality. She was the salt in her life. They also had the connection that they had both married older men, a fact that somehow made their own ten-year age difference less significant. ‘Darling,’ said Fiona, when she picked up the receiver. There was a pause as a match was struck, then a swift exhalation.

‘I was wondering if I could entice you out today? Such glorious weather, pity not to make the most of it.’ ‘What about the shop?’ said Julia. ‘Early closing.’ ‘Surely that’s Wednesday?’ Today was Monday. ‘In my shop it’s whichever day I choose.’ Julia laughed.

‘Seriously,’ said Fiona, ‘Miss Simmons will hold the fort. She’s been dying for the chance to demonstrate her superior knowledge of cretonne.’

‘What did you have in mind?’ ‘I thought we might have a little picnic down by the Martello tower.’ Julia weighed options. It would mean she would miss Peter when he came home for lunch. On the other hand, when he did he would eat as fast as possible and say as little as possible before scampering out again. Long hours stretched ahead.

‘Yes, why not? That would be lovely. What shall I bring?’ ‘Nothing. My suggestion, my treat.’ The tide was out, far out, and the sky was a strong, clear blue with wisps of cloud towards the horizon.

They walked along a path through the salt marshes towards the beach, past shirring reeds, clumps of purple sea lavender and shrubby sea purslane. Down on the flats by the estuary, redshanks probed their spiny bills into the drying mud and a man dredged for cockles. All along the shingle the groynes were exposed, the wooden posts, some rotten and leaning, like the serried rows of teeth in the gaping mouth of a vast marine creature. Over on the hill to the north were six black cannons, remnants of another war, a threatened invasion over a century and a half ago. Gulls screamed and swooped.

‘Oh, look, here’s a mermaid’s purse,’ said Julia, bending down. Mermaid’s purse: the seedpod of a dogfish. The small matt-black pouch, which was ugly and vaguely menacing, had a pair of thin curving prongs at either end. Such finds were precious to her, tokens of good fortune, as were holey stones.

She picked it up from the shingle, put it in her pocket and made a wish: Protect my family. Fiona smiled. ‘Ever the beachcomber. You look all of sixteen in that dress.’ ‘Untidy, you mean.’ Julia brushed her hair back from her forehead. ‘Nonsense,’ said Fiona. ‘Charming.’

She herself was smart as a bandbox in a navy frock with a while collar and white dotted stitching on the bodice and down the pleats of the skirt. On her, navy was vivid: everything was against the blaze of her red hair.

Tortoiseshell-framed sunglasses, bright lipsticked mouth. No one in town dressed like Fiona; no one else could have carried it off, or would have particularly wanted to. (Julia thought her a little vain.) ‘Let me take the hamper.’

‘Darling. I thought you’d never ask,’ said Fiona.

When they rounded the bay the Martello tower came into view. Squat, egg-shaped in plan, it was made of London stock brick long ago weathered grey. Similar examples of these Napoleonic defences were strung out at intervals all along the east and south coasts. The pointed end, where the wall was thickest, faced the sea. High above the ground was a door, which would have been reached by rope ladder pulled up behind the defenders. Had the need arisen in those distant days, they would have fired from the roof.

‘Sun or shade?’ said Fiona. ‘If we can find any shade, that is.’ Julia shielded her eyes against the glare. ‘The film people are here.’ ‘Are they?’ ‘Yes.’ She pointed. A dozen or so men were grouped around a camera. One of them, tallish, fair-haired, was doing a fair amount of waving and shouting. Surrounding them at a slight distance was a small crowd of onlookers. ‘So they are.’ ‘Did you know they would be?’ Fiona smoothed her skirt. ‘I might have done.’ Julia said, ‘You’re outrageous.’ ‘No reason why we should miss out on the fun.’ ‘Carpe diem?’ ‘That sort of thing. Let’s face it, it’s all going to get pretty grim soon.’ ‘So Richard says.’ And he had been one of the lucky ones, still stationed at his training camp when they’d signed the Armistice. Although by no means unscathed: a brother killed, and two cousins. They crunched over the shingle.

‘Which reminds me,’ said Fiona, ‘I must dig out my lease.’ Lease? thought Julia. Fiona’s conversation was elliptical at the best of times. She had a tendency to drop you down in the middle of her thought processes. ‘What’s that got to do with the war?’ ‘Nothing whatsoever.’ Richard – solicitor – legal document – lease. That would be the way the dots joined up. They had been making their way rather aimlessly in the direction of a small fishing boat pulled up on the foreshore, which, aside from the Martello tower, was the only other distinguishing feature of this broad stretch of shingle. ‘Here?’ said Julia, setting down the hamper.

‘Good a place as any.’ Julia smiled to herself. Of course it was. They had a perfect view of the filming. Like everything Fiona laid her hand to, the picnic was beautifully done. Dainty cucumber sandwiches, devilled eggs with a welljudged hint of curry powder, a sponge cake, dark juicy plums from the tree in her garden and a thermos of tea which they drank out of the proper china cups with which the hamper, with its neat leather fastenings, was equipped, along with proper china plates, cutlery and a cruet, all snug in its wickerwork interior.

By the time they had finished the onlookers had drifted away, leaving the film crew to do whatever it was they were doing, which appeared to be nothing at all. ‘I must say, I fail to see what the fuss is about,’ said Fiona, lighting a cigarette. ‘It’s like watching paint dry.’ ‘Mmm.’

Julia leant back on the rug, licking plum juice from her fingers. There was a faint smell of creosote and a stronger reek of fish coming from the boat in whose lee they sheltered and the sun was warm on her neck and her bare legs. She felt buoyed up by the simple pleasure of eating in the open air, and by talking, although Fiona had done most of that. ‘The shop’s clean out of blackout,’ Fiona was saying. ‘Which is a pity, because that silly Lumm man came round yesterday and told me to put up blinds in the conservatory. Whatever for? We never sit in there after dark.

The ARP training must have gone to his head. Now I’ll have to do it with paint, and what will happen to my poor cuttings?’ Fiona talked as she breathed. It spooled out in ribbons. From the blackout she somehow got on to the topic of her daughters.

Ginny, who had failed her School Certificate, was now sitting around at home all day lacquering her nails, playing gramophone records and writing horrid things in the diary she hid under her mattress. Her younger daughter, Avril, was turning out to be surprisingly good at science. Where had that come from? Mr Moodie, her next-door neighbour, had developed a religious mania and could be heard praying aloud in the garden.

‘I distinctly remember from RE,’ Fiona said, ‘that the general idea was that one should communicate with one’s Maker silently and in the smallest, most private space, which in my mind I imagined to be our old broom cupboard under the stairs. Not in plain view by the dahlias.’ She broke off. ‘Oh, here comes trouble.’ Julia sat up. ‘Something happening at last?’

Then she caught sight of Peter coming round the bay. He had that rapt, selfcontained expression of the schoolboy on holiday. She waved at him and he carried on where he was heading, which was towards the film people. ‘Peter!’ she shouted. He briefly turned in her direction but didn’t stop. Fiona said, ‘I recognize that look. I get it from Avril all the time. “Oh, am I related to you in some way? I think not.” That look.’ ‘He’s started to call me Madre,’ said Julia. She missed him calling her Mummy.

‘Better Madre than Mater,’ said Fiona. ‘Richard finds it amusing.’ ‘And how is the Sainted One?’ Julia prickled with irritation.

Whenever Fiona mentioned Richard, there was always an edge in her voice: she couldn’t imagine why. ‘He thinks he might have found someone who’s prepared to defend Perry Clayton.’.

‘I can’t think of anything more depressing than defending a guilty man,’ said Fiona. ‘Innocent until proven guilty.’ ‘With all those witnesses?’ ‘If this were France he might walk free,’ said Julia. ‘Crime of passion.’

Fiona said, ‘Well, thank God this isn’t France. What he did to the Dowler lad was brutal.’ There was another thermos in the hamper. She reached for it. ‘Oh, I couldn’t,’ said Julia. ‘I’ve drunk so much tea.’ ‘It’s not tea.’

Fiona uncorked the thermos and produced two glasses from the miraculous hamper. Poured. An astringent, oily, lemony smell. ‘What is it?’ Julia took the glass, which had been immediately chilled by its contents. She sniffed. ‘Gin?’ ‘Cheers,’ said Fiona. A bit early for a drink, thought Julia, but she drank it anyway. Fiona had that effect on her. Even so, she wondered whether her friend might have a little problem.

The sea gargled stones in its mouth. The tide was beginning to turn and the shushing sound it made reminded Julia of what she had been trying to ignore for the past ten minutes. She squirmed. ‘I’m never going to make it home.’ ‘Go behind the boat.’ ‘Fiona!’ ‘No one’s looking.’ Julia laughed. ‘What if they do?’ ‘They won’t.’

Nelson said the white letters painted on the boat’s side. She squatted and peed. The relief was enormous. Afterwards, she realized it was getting late, the shadows lengthening. Down by the Martello tower the film people were still doing, or not doing, what they had been doing all afternoon and Peter was still hanging about, watching them. Fiona was sitting on the rug smoking.

‘Better now?’

‘Much.’

She held up the thermos. ‘Have another.’

‘I shouldn’t. I really ought to get back. Let me see if I can winkle Peter away and then I’ll help you pack up.’

Julia walked across the shingle in the direction of the sea and incoming tide, and the stones rolled around under her feet. Sun, air, gin, a little light-headed. For the moment: happy. As she approached the tower she saw nothing glamorous at all about the proceedings at all. Close up they were a rackety-looking lot, dirty jerseys and so forth. One was consulting a clipboard; another was rolling up a tape measure; others were making adjustments to the camera, whose focus was unclear. Cabling snaked over the ground and a hum came from a black box she assumed must be a generator. No one noticed her approach.

‘What?’ said Peter, swinging round, when she touched him on the arm.

‘Don’t say “what?”, it isn’t polite. Time to go home.’

As she might have expected, he dug in his heels. There followed a good deal of plea bargaining of the ‘ten more minutes’, ‘five more minutes’ variety, which was beginning to exasperate her, rub off her good mood, when she looked up and saw that the man who appeared to be in charge, the director she supposed, was staring at her. He was around her age, tall, thin, with a beaky nose and a lock of tow-coloured hair falling over his forehead. She caught his eye. In that instant some odd connection was made, what she could only describe to herself as a meeting. It was shockingly familiar. New and jolting. Both at the same time.

‘Your property?’ He nodded at Peter. A mobile mouth, rather wide, rather full, rather sad, and a voice she could have sworn she knew, a voice that her body heard. It was as if he played a chord right through her.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I hope he hasn’t been disturbing you.’ ‘Not at all.’

‘You see?’ said Peter. ‘Just another few minutes.

If I Could Tell You

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- ISBN-10: 0143130439

- ISBN-13: 9780143130437