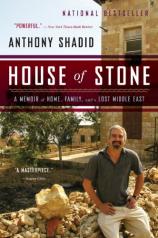

House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East

Review

House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East

Following the 2006 war in Lebanon, Anthony Shadid, renowned war correspondent for the Washington Post and New York Times, returns to the house built by his great-grandfather in southern Lebanon. Discovering a half-exploded Israeli rocket in the wall of the second story of this ancestral home in the town of Marjayoun, Shadid leaves for a few hours, then returns with an olive tree. “Its trunk was no thicker than a pen, and its branches arched no higher than my chest.” But he plants this spindly tree 10 feet away from olive trees planted in his grandmother’s time. As he does, this man, who has “never been the type to stay home,” makes a promise to himself to restore this crumbling house to a home for his daughter and her generation.

"A treatise on the meaning of home and an evocation of a part of the world that since World War I has known very little else but war or the threat of war, HOUSE OF STONE opens our eyes to the pathos and color of this region."

The story of the restoration serves as a scaffolding for an exploration of Shadid’s family history, as well as a window into current life in this war-weary region. Shadid can depend on neither the electricity nor the foreman and workers he hires to work on the house. Marjayoun is a shadow of its former self. Abandoned, empty homes surround the dwindling number of inhabitants. Yet those inhabitants are as nosy, combative and opinionated as ever. Most of them believe Shadid is some kind of spy. Even his new friends think his mission is foolish. “This house belongs to so many people,” says his friend, Shibil. “It’s not yours.”

As might be expected from a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, Shadid laces his memoir with telling details. The missing from his friend’s neighborhood are “either studying in Beirut or working abroad --- in America or the oil-driven sprawl of places such as Dubai, where women outfit shrieking infants in Versace and all the mirrored surfaces are strictly self-reflective.” But the author’s personal voice is also abundant, revealed in his desires and frustrations over the house and in his re-imagining of his grandparents’ journeys from the fallen Ottoman Empire to America in the 1920s. Particularly moving are the stories of parents bidding their children a probably final goodbye, sending them off with aunts and uncles to join relatives already safely in Oklahoma City.

Soon, Shadid realizes that when his foreman Abu Jean says “tomorrow,” it doesn’t mean tomorrow but rather sometime in the future. And Abu Jean is right; the work on the house does get done, the coveted tiles purchased, cleaned and laid again, the original arches restored. When Shadid is released in 2011 from being captured and beaten in Libya, the home he returns to is the one he rebuilt in Marjayoun, with a new wife and young son.

A treatise on the meaning of home and an evocation of a part of the world that since World War I has known very little else but war or the threat of war, HOUSE OF STONE opens our eyes to the pathos and color of this region. Sadly, Anthony Shadid did not live to see its publication. He died this past February while reporting from Syria.

Reviewed by Eileen Zimmerman Nicol on March 15, 2012

House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East

- Publication Date: February 5, 2013

- Genres: Nonfiction

- Paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Mariner Books

- ISBN-10: 0544002199

- ISBN-13: 9780544002197