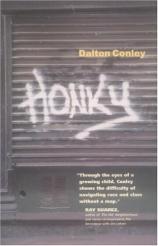

Honky

Review

Honky

The autobiographical conditions that spurred Dalton Conley's thoroughly original memoir, HONKY, resemble some strange "what-if?" scenario. But if the events recorded herein suggest a made-for-TV-movie premise too incredible to be believed, they are nonetheless recorded in an objective, candid manner that reveals the voice of a writer far more concerned with social analysis than mere sensationalism. HONKY tells the story of a boy who must come to terms with his conspicuous whiteness in an African-American/Latino ghetto. Although being "white" usually ensures certain privileges in American culture, Conley's skin proves an increasingly difficult fact he must face in New York City's racially tense climate of the '70s and '80s.

In the opening chapter of HONKY, Dalton admits that as a young child he was quite ignorant of his ethnic difference. "…[I]n the projects people seemed to come in all colors, shapes, and sizes, and I was yet unaware which were the important ones that divided up the world." His coming-of-age, however, is marked by an increased awareness of his unique cultural problem: Conley was too poor to be fully accepted into white middle-class circles and too white to be a member of the gangs that populated his neighborhood.

The early sections of HONKY dramatize problems he and his Irish-Jewish family encountered in attempts at assimilation. Conley learns, for example, that he is the only member of his class who does not receive corporal punishment because it would be unthinkable for a black teacher to hit a white child. At the same time, black parents are eager to have their children disciplined in the schools --- a value difference Conley's mother is not willing to adopt. After transferring to an elementary school across town in the Village, Conley experiences what it means to be among white students for the first time:

"I would learn that the most popular kids tended to be those whose parents were the richest or most powerful or held the most prestigious jobs. In my old school there had been no such hierarchy of which I was aware --- probably because no one's parents were rich, powerful, or prestigious in any sense of the word. There, each kid invented his own place in the social network…by brute force."

Conley's understanding of this complex social hierarchy only makes him more self-conscious. His position throughout the book is that of marginal participant/perpetual observer. Always slightly outside the boundaries of either the white group or the ethnic groups, Conley's sense of identity is at best confused and fraught with guilt. In fact, guilt becomes a continuous undercurrent throughout the entire narrative. The word is mentioned no less than ten times in connection with various events. Whether Conley is guilty about not being hit by his black teacher or ashamed of bringing his white friends from the Village to his run-down street, he is always acutely aware of social schisms and dynamics most people do not need to think about. The level of guilt he feels at once demonstrates the depth of his sensitivity and explains his social awkwardness.

Although HONKY addresses deeply layered social concerns, the text is quite accessible and exciting to read. Many of the scenes are peppered with a violent, suspenseful tension that only makes the narrator's predicament all the more engrossing. But whether Conley is getting threatened with a knife or eyeing the darkness of his building's stairwell for possible muggers, rapists, or murderers, the tone never becomes tragic. In fact, Conley's ironic, adult voice often interjects subtle doses of humor throughout, especially when he wryly observes his eccentric parents.

Speaking of which, HONKY's story-beneath-the-story, in which his mother and father have forsaken a world of economic prosperity and opted for a cultural nightmare ("downward mobility") shows two people so committed to their art that they would forfeit their cultural cache for it. Whether the choice they made makes them heroic, selfish or foolish is irrelevant; they had the luxury of making this choice. And that, Conley reminds us, is the ultimate difference between being white and being "of-color" in America.

Reviewed by Tony Leuzzi on October 2, 2000

Honky

- Publication Date: October 2, 2000

- Genres: Nonfiction

- Hardcover: 242 pages

- Publisher: University of California Press

- ISBN-10: 0520215869

- ISBN-13: 9780520215863