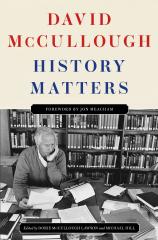

History Matters

Review

History Matters

With two Pulitzer Prizes and numerous other awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, to his credit, by the time of his death in 2022 at age 89, David McCullough was recognized as one of America’s greatest and most popular contemporary historians. Whether he was writing about the Johnstown Flood, the building of the Brooklyn Bridge, or the life of John Adams, he set a high bar for those who follow in practicing the craft of narrative history.

Edited by his daughter, Dorie McCullough Lawson, and his longtime researcher, Michael Hill, HISTORY MATTERS is a slim collection of some of “DMcC’s” (as they refer to him) essays, speeches and miscellaneous pieces, many never before published. It bears a superficial resemblance to, while somewhat more eclectic than, his 2017 collection of speeches, THE AMERICAN SPIRIT. McCullough’s fans will enjoy this opportunity to be reminded of his gifts, while those new to his work may find in it encouragement to seek out more of his writing.

For all the diversity of these 20 pieces, there are a few ideas and themes that serve as connective tissue. McCullough credits two of them to a Paris Review interview with the writer Thornton Wilder, a fellow at McCullough’s college at Yale University, where he graduated in 1955. (HISTORY MATTERS contains McCullough’s own instructive interview on “The Art of Biography” with that magazine in 1999.)

"McCullough’s fans will enjoy this opportunity to be reminded of his gifts, while those new to his work may find in it encouragement to seek out more of his writing."

In his interview, Wilder observed, “I think I write in order to discover on my shelf a new book that I would enjoy reading or to see a new play that would engross me.” Elsewhere in the conversation, as McCullough describes it, Wilder “talked about the difficulty of writing about the past in a way that does not rob events of their character of having occurred in freedom. How to convey the reality that nothing ever had to happen the way it did and that no one ever knew how things would turn out?” In several of the volume’s entries, McCullough goes on to add one of the principles that informed his work: “Indifference to history isn’t just ignorant, it’s rude. It’s a form of ingratitude.”

Guided by these touchstones, McCullough viewed himself as a storyteller. In a foreword to HISTORY MATTERS, Jon Meacham calls him “a central figure in a renaissance of popular history.” McCullough took as his role models historians like Barbara Tuchman, Bruce Catton, and the lesser known but multitalented writer and artist Paul Horgan, a man he looked to as a mentor and friend and is the subject of an admiring tribute here. In all his work, McCullough strived to enter deeply into the world of his subjects, and to see that world clearly and sympathetically through their eyes.

That’s true, for example, of his vivid description of the fortuitous escape of George Washington’s army from Brooklyn Heights in August 1776 in “Take Luck to Heart,” his 2018 commencement address at Providence College, or “A Conversation About George, his laudatory brief portrait of the first president in a speech at the Library of Congress in 1999. In an eponymous piece about our 33rd president, Harry Truman --- the subject of McCullough’s first Pulitzer Prize-winning biography --- he shares some trenchant insights about the importance of character that might be useful yardsticks in evaluating the conduct of those who occupy the office.

“Getting Through to Schlesinger” is a charming account, discovered in McCullough’s papers, of the then-27-year-old’s urgent effort to communicate what he thought was a winning policy proposal to Arthur Schlesinger, a prominent speechwriter for John F. Kennedy, in the heat of the 1960 presidential campaign. “The Good, Hard Work of Writing Well” contains some useful craft advice, while “Reading and Writing: A Recommended Reading List” is one of a pair of pieces that highlight some of McCullough’s favorite books.

A few of the entries collected here --- like McCullough’s tributes to the artist Thomas Eakins, his Yale architecture professor Vincent Scully, or the popular novelist Herman Wouk --- are less engaging. But their brevity and, above all, McCullough’s unbridled enthusiasm for these subjects doesn’t spoil one’s enjoyment of the volume as a whole.

In addition to his skill as a writer, McCullough was a talented artist. The front endpaper of HISTORY MATTERS features a watercolor of the home on Martha’s Vineyard where he and his wife of almost seven decades, Rosalee, lived for many years. The volume’s back endpaper contains another painting of that home’s backyard and the eight feet by twelve shed in which McCullough worked, dutifully turning out roughly four pages of prose daily on a Royal typewriter manufactured in 1941 that he purchased in 1965 (the subject of the affectionate tribute, “A Bit of History About My Typewriter”), in the end adding up to 12 books.

While McCullough generally avoided entangling himself in the political controversies of the moment, in his speech “American Values,” he described himself as a “short-range pessimist and a long-range optimist” who “sincerely believe[d] that we may be on the way to a very different and far better time.” Anyone who relished his writing will take great pleasure from this retrospective. Their only possible complaint will be that it’s too short, and one hopes that more material from this beloved writer’s archive may be forthcoming someday.

Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg on September 19, 2025

History Matters

- Publication Date: September 16, 2025

- Genres: Essays, History, Nonfiction, Political Science

- Hardcover: 192 pages

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- ISBN-10: 1668098997

- ISBN-13: 9781668098998