Excerpt

Excerpt

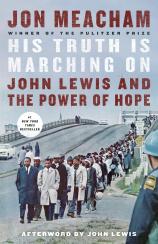

His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope

Chapter One

A Hard Life, a Serious Life

Troy, Alabama: Beginnings to 1957

For John Lewis, slavery wasn’t an abstraction. It was as real to him as his great-grandfather, Frank Carter, who lived until his great-grandson was seven. Light-skinned, hardworking, and self-confident, Carter, whom Lewis called “Grandpapa,” had been born into enslavement in Pike County, Alabama, in 1862. The family has long believed that a white man was likely Frank Carter’s father—Carter and his own son, whose name was Dink, were, Lewis recalled, “light, very fair, and their hair was different, what we could call good hair”—but the subject was shrouded in secrecy and silence. This much is clear: The trajectory of the infant Frank Carter’s life was fundamentally changed on Thursday, January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln declared the enslaved in the seceded Confederate States of America were now free, and by the ratification, in December 1865, of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery “within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Coming of age in Reconstruction and under Jim Crow, Carter was driven and skilled in the world available to him. Yet the “new birth of freedom” of which Lincoln had spoken at Gettysburg in 1863 had failed to come fully into being after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in 1865. Within eight months of the war’s end, Alabama’s legislature had instituted a Black Code to curtail the rights of African Americans and give the old ways new form and new force. In 1866, the federal government, driven by Republicans in Congress, sought to bring interracial democracy to the South. The reactionary Black Code was repealed; new constitutions were written; black people were by and large allowed to vote; and African American candidates were elected to federal, state, and local office.

White reaction was fierce. The Ku Klux Klan was founded in these postbellum years—a Confederate general named Edmund Pettus was a grand dragon—and, by 1901, when Frank Carter was nearly forty, white Alabama had reverted as much as it could to an antebellum order by legalizing segregation, circumscribing suffrage, and banning interracial marriage. At the dawn of a new century, then, the old color line had been redrawn and reinforced.

Alabama’s 1901 constitution establishing white supremacy had been debated in Montgomery from May to September of that year, ending in time for the cotton harvest. Fifty miles away from the state capitol, Frank Carter leased his land from J. S. “Big Josh” Copeland, a major figure in Troy, the Pike County seat. Carter worked his way to an unusual level of sharecropping called “standing rent,” which meant he paid Copeland to lease the land but did not owe the landlord any of his yield beyond the rent. Diligent, resourceful, and determined, Lewis’s great-grandfather did the best he could under the constraints of his time. “He couldn’t read or write,” his great-grandson said, “but he could do financial transactions in his head faster than the man on the other side of the desk could work them out with a pen and paper.” Carter took great pride in just about everything he did. “He would sit in his rocking chair on his porch,” John Lewis recalled, “and he acted like he was the king.”

In a way, he was—at least of the piece of Pike County that came to be known as Carter’s Quarters. It was there, in 1914, that his granddaughter Willie Mae was born to Frank’s son Dink. In 1932, she married Edward Lewis, who had been born (along with his twin sister, Edna) in 1909 in Roberta, Georgia. Eddie’s mother, Lula, had come to Carter’s Quarters after a separation from her husband, Henry. Willie Mae and Eddie met at Macedonia Baptist Church and fell in love. He called her “Sugarfoot”; she called him “Shorty.”

They were to have ten children: Ora, Edward, Sammy, Grant, Freddie, Adolph, William, Ethel, Rosa (also called Mae)—and John Robert Lewis, who was born in a shotgun shack in Carter’s Quarters on a cold Wednesday, February 21, 1940. Readers of The Montgomery Advertiser that day saw headlines about the German sinking of three British ships and Democratic anxiety about President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s silence on whether he’d seek a third term. Closer to home, The Troy Messenger reported on a local man’s suicide—he had jumped from the nineteenth floor of a downtown Montgomery hotel—and announced an upcoming fiddling contest in the County Activities building that would include Harpo Kidwell, “national champion harmonica king.” The Troy paper also published a biblical “Thought for the Day,” drawn from First Peter: “Beloved, think it not strange concerning the fiery trial which is to try you.”

It was a harrowing era to be black, Southern, and American. In June 1940, when John Lewis was four months old, Jesse Thornton, a twenty-six-year-old churchgoing African American man who lived twenty miles away from Troy, in Luverne, Alabama, was standing outside a black barbershop when a white Luverne police officer walked by. Thornton allegedly failed to address the policeman with the honorific “Mister.” Thornton wasn’t thinking, or at least wasn’t thinking the way a black man was supposed to think under a regime of white supremacy. He was lynched, his corpse dumped in a nearby swamp. Thornton’s body was found several days later floating in the Patsaliga River, mauled and gnawed by vultures and buzzards. According to the Luverne newspaper, “the cause of his death is a mystery that will probably never be solved.” In a typewritten report on the incident, Charles A. J. McPherson, the secretary of the Birmingham branch of the NAACP, wrote, “These lynchings are organized and hushed up too in Hitler fashion and who knows how often?”

Terror could strike African Americans at any time—and justice was bitterly elusive. On the evening of Sunday, September 3, 1944, in Abbeville, Alabama—about fifty miles from the Lewises’ Troy—a twenty-four-year-old African American woman, Recy Taylor, was walking home after services at the Rock Hill Holiness Church. She had a husband and a two-year-old baby. In the darkness, seven white men kidnapped her at gunpoint; six of them gang-raped her. “I’m begging them to leave me alone—don’t shoot me—I got to go home and see about my baby,” Mrs. Taylor recalled. “They wouldn’t let me go. I can’t help but tell the truth of what they done to me.” The NAACP in Montgomery heard about the case and asked one of its members, a woman who happened to have family in Abbeville, to go over and investigate. Rosa Parks accepted the assignment, learned the details of the attack, and helped organize a campaign for justice for Mrs. Taylor, who bravely spoke up about the crime. But there would be no justice: All-white grand juries twice refused to indict the well-known assailants.

There seemed no hope. An omitted “Mister” might get you dumped in a swamp on an otherwise unremarkable summer day; walking home from church could lead to horrific sexual violence. “We know that if we protest we will be called ‘bad niggers,’ ” the novelist Richard Wright wrote in his 1941 book Twelve Million Black Voices. “The Lords of the Land will preach the doctrine of ‘white supremacy’ to the poor whites who are eager to form mobs. In the midst of general hysteria they will seize one of us—it does not matter who, the innocent or guilty—and, as a token, a naked and bleeding body will be dragged through the dusty streets.” That was the way of the world into which John Lewis was born.

His first memory was of his mother’s garden. “There was a little gate, and when you opened the gate, there was a large bucket that filled with rain, and we used it to water the vegetables and the flowers and the plants,” Lewis recalled. “I loved to make things grow, to pour out that water. I somehow always knew that water was good. I would always love raising things.”

His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope

- Genres: Biography, History, Nonfiction, Politics

- paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: Random House Trade Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 1984855042

- ISBN-13: 9781984855046