Excerpt

Excerpt

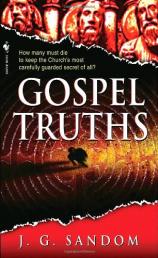

Gospel Truths

Prologue

AMIENS, FRANCE

May 20th, 1990

IT RAINED AS MAURICE DUVAL DROVE HIS BATTERED BLUE Peugeot through

the gate behind Place Saint Michel, onto the crackling gravel drive

which skirted the cathedral and the ancient Bishop’s Palace.

As he neared the palace, Maurice dropped his cigarette through the

open window. The rain was falling fiercely. The white stone window

frames glimmered dimly between muddy brick. The wet slate roof

shimmered through the trees. Maurice cut the engine and the car

crawled to a stop.

Behind the falling rain, the sound of organ music swelled the

evening air. Someone was practicing late, he thought. The night

watchman was nowhere to be seen. Maurice slipped his porkpie hat

onto his head and took the pistol out again, to check the

ammunition, to calm himself.

Above the southern wing of the palace, the rose of the

cathedral’s transept window glowed red and cobalt blue. In a

year or more the renovation of the palace would be finished, and a

trade school would replace the emptiness. But Maurice knew that to

the farmers and fishermen of the province the building would always

remain the Bishop’s Palace. The emblem of Picardie was

a snail, after all, and despite its name a bishop had not slept

within the residence for a hundred years. The windows were boarded

shut, the walls emblazoned with graffiti. He closed the car door

noiselessly and headed for the southern wing.

A cement mixer stood by the door leading down into the basement.

Maurice hesitated. Was he too late? He pulled a flashlight from his

jacket and turned it on. The basement door was closed but he could

clearly see a piece of paper wadding stuffed beside the bolt. The

organ music had stopped. Cold rain washed the palace walls. He

pressed his elbow to his side to feel the gun again. Then he opened

the door and stepped inside.

The air in the basement was sweet with Noviganth and other

chemicals. Empty Kronenbourg beer bottles lay strewn across the

floor and on the dusty windowsills which faced the outer palace

square. Maurice moved through the room, illuminating the corners

with his flashlight. He had almost reached the door leading up into

the palace when he saw the hole. It had been neatly concealed

behind a pile of earth, cut in the ground right at the foot of the

southern wall. He walked slowly across the basement wing and shone

the flashlight down into the opening. A piece of corrugated iron

partially blocked the shaft, but he could still make out a kind of

tunnel, hemmed in by stones. He tossed his hat on the ground and

began to kick the dirt roughly to the side.

It took him only a few minutes to lift the corrugated iron high

enough for him to slip down into the opening. He moved headfirst,

the flashlight bouncing in his hand as he dragged himself along on

his belly. Suddenly the organ music echoed up the passage, and he

realized he was moving underneath the cobbled road between the

palace and the great cathedral. He crawled forward for another

fifteen meters in this fashion when he sensed the air grow fresher

about his face. The stone tunnel turned abruptly to the left. Then,

just as suddenly, it opened onto a larger corridor below him. He

shone the flashlight through the darkness. The floor of the

corridor was a good two-meter drop from the mouth of the

tunnel.

Maurice lowered himself carefully down into the corridor. As he

turned, he saw the lintel of a narrow doorway to his left. It led

into a small room, a closet really, around which ran a low stone

bench.

Beyond the closet the corridor curved sharply to the right. Maurice

started slowly up the darkened passage. The music seemed louder

now, and for the first time he realized that it was not

particularly good, just a patternless series of notes, an endless

repetition.

He turned the flashlight off and crouched clumsily against the

wall. Someone else was in the passage up ahead.

Whoever he was, wherever he was, the stranger moved quietly. Then

he stopped.

Perhaps a minute passed before Maurice could hear the stranger move

again. There was the sound of cloth on cloth, of metal on stone. He

switched the flashlight on, aiming it into the darkness like a

weapon.

A man’s face turned to face the glare, his arms laden with

objects—a book, a scroll, a golden cross. His eyes were

charged with terror as he leapt into the light. Maurice pulled out

his gun just as the cross descended, glittering. The flashlight

tumbled from his

hand, dragging the darkness down. He pulled the trigger to the

sound of breaking glass.

There was a dull thud as the two men came together, and then the

cold retreating echo of a cry.

“That was close.” Father Marchelidon lifted his hands

from the keyboard. He glanced through the opening in the wall of

the organ room to the cathedral floor below.

The sound of thunder followed. “Did you hear

that?”

The bearded man beside him shrugged. “The wind,” he

suggested. “Thunder and wind.”

“It sounded like a scream,” the priest said.

“Someone heard your playing.” The bearded ma laughed

and clamped an arm about his companion’s narrow shoulders.

“The ghost of Antoine Avernier, no doubt. Have I told you the

story of his death? It’s one of my best. He carved the choir

stalls, you know.”

“Save it for the tourists, Guy.” The priest looked down

again into the dark basilica. Nothing stirred and yet the shadows

seemed a little longer, the cathedral colder.

The night watchman shone his flashlight through the windshield of

the blue Peugeot. He had not noticed it pull in, and this worried

him. It was his boss’s car.

“Maurice?” The rain fell heavily from the darkness

above, stinging his eyes. There was no answer.

“Maurice.” He shone his flashlight round the square and

sighed. It was a lonely job, night watchman, not suited to his

friendly temperament, his unfashionable sense of camaraderie.

He turned from the car and began to walk back toward the

Bishop’s Palace. The basement door was slightly ajar. He ran

his fingernails along the gap. This was unusual. This was

wrong.

With another sigh he leaned down, careful to support his back, and

picked up a piece of rain-soaked scrap wood from the ground. If it

were the Flichy boys again, he would need it. They had evil

temperaments, he thought, unsuited to anything but petty crime and

pimping. They would end up dead someday, not just dead but casual

dead, in an alley, in an oily harbor with their pockets empty. He

opened the door.

Perhaps he had had too much again. But it was cold for May, he told

himself. And besides, his bottle was his only stalwart friend these

days, the only ally left. The light bounced off the far wall and

returned. He scanned the basement carefully, the corners and the

windowsills. Then he smiled and called out loudly once again,

“Maurice.” There was no answer. He checked the door to

the main part of the palace. It was locked. He turned away and in

that movement he resolved, as he had done already twice that month,

that he would leave the bottle home next time. He was too old to

rely upon his reflexes alone, to think his instincts would preserve

him as they had done in Vietnam and in Algeria. The breaking of a

twig had saved him once, the splinter of a palm across the path.

But the Flichy boys would never give him that. They were too

cautious, and providence had left his life a droplet at a

time.

The night watchman moved back through the basement room, not once

aware of the two hands which pushed the dirt up slowly from below,

until the hole in which Maurice had vanished only thirty minutes

earlier had disappeared from view, until the ground was smooth and

featureless and almost all was as it had been.

Part One

Chapter One

LONDON

August 10th, 1991

WAS LATE, OR EVERYONE ELSE WAS EARLY ONCE again. Nigel Lyman dug

his elbows into his sides and leaned into the morning, moving with

the cadence of a military parade. He was not a particularly tall

man, but there was a solidity about his body, a tightness of the

neck and shoulders, that lent itself by nature to this kind of

grim, determined walk. He moved as if to prove the definition of a

line.

A fierce breeze plucked the rain, and as Lyman walked he pointed

his umbrella at a dozen different clouds, jabbing at the fickle

wind. The sidewalk was almost empty. Most of the city was at work

already, save for a few resilient shoppers, the tardy secretaries,

the intentionally lost. The street coursed dreamily along, the shop

walls rising to the rain, the gray slate roofs and grayer sky of

London.

Lyman turned off the street and entered the police station. A small

crowd waited by the lift. He passed them with a terse hello, and

noticed—as he headed for the stairwell at the back—that

a line of water trailed his wet umbrella down the hall. It was

going to be one of those days, again.

He took the steps two at a time, trying to ignore the dark familiar

landmarks of the first few floors, the sergeant constable on duty,

the holding cells, the paperwork policemen, where Dotty Taylor

worked with rows and rows of numbers in accounting.

When he reached the fourth floor, he stopped and took his scarf and

coat off, dropping them delicately across a battery of pipes near

the door. Then he hung up his umbrella, the bent spoke closest to

the wall. No one gave him much more than a passing glance as he

entered the office, but Lyman knew they registered his presence. It

was almost ten A.M. Some were just too polite, he thought, too

bloody shy, or too embarrassed to say anything. Some really

didn’t care.

And then there were the rest, who hoped that one day his apparent

lack of gumption would be noticed but who refused to drag his

failings from the shadows by themselves, afraid perhaps that adding

peccadillos to his already damning sins might seem

vindictive.

He walked between the rows of desks. Eight policemen shared the

office, and most sat with their faces turned away, trying not to

look at Lyman. Some read reports with studied concentration. Some

talked in whispers on the telephone.

Lyman sat down at his metal desk. It was the tidiest in the room,

the surface empty save for an ancient telephone, an ashtray, and a

battered old PC.

“Starting early,” Inspector Blackwell said beside him.

Lyman turned, facing Blackwell and the open window. It was always

open, sun or snow. He reached into his pocket, removed a tin of

licorice, and popped one in his mouth.

“By the by,” continued Blackwell, “Chief

Superintendent Cocksedge wants to see you. As soon as you come in.

Hello. Are you there?”

Lyman frowned. “When did Cocksedge poke around?”

“Poke?” Blackwell’s eyebrows seemed to skate

across his forehead. “The detective chief superintendent does

not poke. His representatives may poke. He delegates. He

confers.”

“Just answer the question, Blackwell.”

“He sent the Lemur down at nine.”

“Thanks,” Lyman answered in a kind of cough. His head

hurt. It had hurt since late last night, or even longer. He pushed

his chair away from the desk. “I won fifty pounds in the

football pool yesterday,”

Blackwell crowed.

Lyman ran his fingers through his hair. It was still thick, just

grayer round the edges, like burnt paper.

“Good for bloody you.”

“Now I can pay you back that twenty quid.”

Lyman straightened his suit jacket. “Wrong again, Blackwell.

It’s I owe you.”

Inspector Blackwell smiled. “There you go,” he

said.

“Clever lad. And when exactly, if I may ask, are you going to

pay me?”

Lyman glanced down at his shoes. They were soaked through. He

turned and headed for the door.

“Give him our best,” Blackwell called after him.

“And don’t forget my money.”

Detective Chief Superintendent of Police Brian R. Cocksedge, late

of the Royal Navy, was fond of quoting Siegfried Sassoon in a

dramatic baritone whenever he was struck by the oppressive

realization that Man was, comparatively speaking, barely out of the

trees of Africa. At times, especially when he had been upstaged

again by the New Scotland Yard, he would stand firmly in the

doorway of his office, pitching his voice at no one in particular.

“ ‘When the first man,’ ” he’d cry,

“ ‘who wasn’t quite an ape/Felt magnanimity and

prayed for more,/The world’s redemption stood, in human

shape,/With darkness done and betterment before.’

”

Nigel Lyman reflected on this as he waited for the lift. He had

never really cared for Siegfried Sassoon. To him redemption was a

dubious exercise, an almost Arthurian quest, one which had little

to do with real human motivation, and therefore even less to do

with crime.

He pressed the button for the lift again and uttered a faithless

prayer that the chief superintendent was not in one of his

discoursing moods again. Indeed, he thought, given a choice between

a grim oration and a short farewell, he would prefer the door. What

else could it mean? he asked himself. It was amazing he had lasted

quite this long. The lift doors creaked open. The chief

superintendent’s secretary, Mrs. Clanger, eyed him with a

codlike, blinkless stare. “Ah, Mr. Lyman,” she said.

“Are you absolutely sure you have the time? I mean, after

all.” She looked at her widefaced watch.

Lyman tried to usher up the smile of a conspirator. “Sorry

I’m late. I had an early meeting across the

river.”

Mrs. Clanger did not soften. A moment passed, and finally she poked

her vintage intercom and announced his presence.

“Right. Send him through,” the chief superintendent

bellowed in response.

Lyman walked briskly across the room and opened the door. The chief

superintendent’s office was cluttered and ill lit, but Lyman

took in the details with a single practiced glance: an overfull

metal file cabinet; a faded rose-and-foliage shade atop a standing

lamp; several photographs in neat walnut frames, mostly old navy

friends and famous personages; a sizable portrait of Her Majesty,

Queen Elizabeth II, artist unknown; a rugger ribbon; an honorary

degree from Bristol University; green curtains, standard issue; and

a massive coatrack and umbrella stand, barely visible beneath

several coats of various weights and textures.

Detective Chief Superintendent Cocksedge stood at the window behind

his desk, staring out into the wet gray street. Lollipop crosswalk

lights blinked on and off below, lending his already waxy

countenance an orange patina. “Nasty, isn’t it,”

he said, pulling at his narrow mustache.

“All week,” Lyman answered.

“Yes. All week.” Suddenly Cocksedge turned fully round.

His face was long and pale, with a pair of creases running up and

down both sides of his forehead, like poorly sewn seams.

“Good for pike fishing though, eh, Lyman?” He took a

reluctant step toward his desk. “It says here you’re a

. . .” His hand flipped through a file. “A

‘fisherman of some experience,’ whatever that means.

Surely every boy in England over five years old is a fisherman of

‘some experience.’ What do those people in personnel do

all day? It’s beyond me, I’m sure.”

Lyman remained silent.

Chief Superintendent Cocksedge sighed loudly. He pulled his chair

out and sat formally behind his desk.

“I’ll be honest with you, Lyman. You’re in a

bloody mess.”

“I know, sir.”

The chief superintendent raised a hand. “Don’t

interrupt me, dammit. I’m trying to help you, Lyman.

I’m on your side.” He turned to the beginning of what

Lyman gathered was his file.

There was that picture of his ex-wife, Jackie, on her old bicycle,

Lyman noticed. It was stapled to a set of crinkled yellow pages.

Personnel always used yellow for dependents. Lyman wondered if

there were some logic to the color.

“Now,” the chief superintendent continued. “There

are certain gentlemen here at City of London and at Metropolitan

who are of the opinion that Nigel Lyman’s talents are on the

wane, that after a promising beginning he has fiddled away his

career.” He scanned Lyman’s face. “I am

not one of them,” he added gravely. “Of

course, I won’t pretend to understand your personal feelings

concerning that ghastly business in the Falklands. Frankly, and I

say this as a father as well as a former officer in Her

Majesty’s Navy, I don’t believe it should have anything

to do with the business at hand, with getting the job done. The

Falklands war was nine years ago. Think of the boys who died last

year and this year in Kuwait. Your son’s death, tragic as it

was, was but one part of the price we all pay for decency in this

country.”

“Yes, sir.” Inspector Lyman looked beyond the window.

He had never even known where the Falklands were before Peter had

enlisted. He had only known the name from reading it on those

little plastic tags clipped to the lamb his butcher sold in Golders

Green. One of Jackie’s cousins had once visited the South

Atlantic islands. She had even sent some picture postcards back,

but Lyman could not remember if they were still down in the cellar,

in that box, or if his ex-wife had removed them with the rest of

her belongings.

Jackie had gone back to Winchester after the divorce. The Falklands

war was all but forgotten. Now everyone obsessed about Iraq. And

all that remained of Peter was his little mongrel, George, who had

found his roundabout way back to Lyman. Jackie hadn’t wanted

him. He shed too much. He ruined her clothes. He too was now

superfluous.

“On the other hand,” the chief superintendent added,

chopping a hand through the air, “if the personal life of one

of my men interferes with his work, then I am forced to take a

position. And believe you me, when I take a position, I do so with

vigor. Am I making myself clear?”

“Yes, sir,” Lyman said.

“I took a risk with you, Lyman. I did your uncle a favor. A

lot of people thought that I was being bloody silly, taking in a

country constable, despite your success with that so-called College

Killer. What am I meant to tell them now?”

“That they were right, perhaps.”

“Don’t be an ass, Lyman. Buck up. Pull yourself

together.”

Lyman realized with a start that the chief superintendent was a

desperate man. He scowled behind his desk, meshing his narrow

fingers like a pair of combs, then pulling them apart. If Cocksedge

fell, it would be from greater heights, and this is what concerned

him. The City of London Police were traditionally an

indigenous brood. Cocksedge had been somewhat daring in his hiring

of Lyman, although it had really been the public and the press who

had authorized the move. For Lyman had once enjoyed a fortnight in

the sun, after the daring capture of a history teacher who had

systematically dismembered several young boys at a prestigious

public school in Hampshire. The “Case of the College

Killer,” as the Daily Mail had called it, had thrown

the young inspector live into the hungry crowd. With his newfound

notoriety and Jackie’s passion for the city, he had moved to

London, forever silencing the editorials and all the righteous

politicians who had growled, “Why aren’t there any

Nigel Lymans solving crimes here in London?” He had come and

been forgotten, his flirtation with the people but a summer romance

after all. “I’m sorry, sir,” Lyman answered

finally. “Of course you can’t say that.”

The chief superintendent settled back in his chair, a faint smile

pulling at his lips. “Now, about this Crosley matter,”

he added softly. “Why don’t you tell me, in your own

words, exactly what happened, so that we can settle this thing once

and for all. Sit down. Take your time.”

Lyman pulled a chair up beside the desk. “Thank you,

sir,” he said. He reached into his jacket and removed a pack

of Players cigarettes. “May I?” The chief

superintendent nodded. Lyman packed a cigarette with care.

“It wasn’t just an ordinary case,” he said,

striking a match and lighting up. “That’s why we were

armed, according to the directive.” A blue sigh of smoke

rolled across the desk. “First there was that blond girl with

the gardening trowel in her chest. And then all those

others.”

Cocksedge grunted an acknowledgment. Lyman told him of the

investigation. His voice was calm, devoid of emphasis.

“We thought it was Spendlove all along—Crosley

especially. There was something about him neither of us felt quite

right about.”

He took a long drag off his cigarette, remembering.

“We went to pick him up on Friday morning.”

“Who’s we? Be specific, man.”

“Constable Crosley and I, Detective Sergeant Thompson, and

Constable John Sykes. Thompson and Sykes stayed downstairs,

watching the window, while Crosley and I went upstairs. At first

everything went smoothly. Spendlove appeared as if he’d been

expecting us. We showed him the warrant and he just fell apart,

crying and pulling at his hair. He looked spent.”

“Why wasn’t he handcuffed?”

“We were about to when he bolted for the door. Crosley ran

after him.”

“What did you do?”

“First I shouted down to Sykes and told him what had

happened. Then I followed Geoffrey—Constable Crosley, I mean.

He had tackled Spendlove on the landing. It was then I saw the

knife. Spendlove must have hidden it in his jacket. I was too far

away to help, so I drew my gun and shouted out the

warning.”

Lyman paused. He took a final puff from his cigarette and snapped

the burning head off in the ashtray on the desk.

The chief superintendent swiveled in his chair. “Go

on,” he said.

“Then they both got up. Spendlove was on the far side of the

landing, with Crosley caught between us. That’s when

Spendlove stabbed him.”

“Is that all? Wasn’t Crosley armed? The suspect was

clearly dangerous.”

Lyman nodded. “Yes, he was armed,” he answered

dreamily. “I had my weapon trained on Spendlove. I remember

that. I was just about to squeeze the trigger when Sergeant

Thompson fired. People had already started looking out their doors.

It was a bit of a riot after that, sir, I’m

afraid.”

“I see,” Cocksedge said. “I understand.” He

nodded firmly. “You never had a clear shot, is that it? You

couldn’t pick him off while they were struggling.”

Lyman nodded. “Yes, that was it. I couldn’t really see.

He was a good lad, Crosley. Too young to die like

that.”

“Of course he was,” Cocksedge answered angrily.

“But he knew what his job was. He knew the risks. Don’t

go blaming yourself now.” The chief superintendent shook his

head. “He was about your son’s age, wasn’t he?

Yes, I thought so. It wasn’t your fault, Lyman. It was just

bad luck. The question is, of course, what now?”

“Sir? A review, I suppose.”

“Do you? Well, don’t suppose. Let me do the supposing.

That’s my job. I don’t think we need a review. It seems

pretty clear to me. Crosley didn’t use his gun, did he? That

mistake cost him his life.” Cocksedge reached unceremoniously

across his desk and pushed a button on the intercom.

“Where’s Randall, Mrs. Clanger?”

“Out here, sir,” crackled the reply.

“Well, send him in. I haven’t got all day.”

The chief superintendent stared at Lyman with a flat, mishandled

smile. Lyman felt he should respond, but he wasn’t sure what

to say. He had expected a dismissal, or a suspension at the very

least. Now Cocksedge did not even want to open a review. Lyman

heard the door behind him open, and then the almost soundless,

precious patter of familiar footsteps. It was the Lemur,

Superintendent Terry Randall. Lyman stood.

Superintendent Randall was a tiny compact man with curly light

brown hair and a pronounced jaw. It was this almost simian aspect

of his countenance that had earned him his nickname; that and his

quick ascent of the police department’s hierarchy. Just as

the lemur had survived the age of dinosaurs, so Randall had

succeeded where his senior but ungainly competition had

succumbed.

“Right,” Cocksedge added, waving Randall to the side.

“I think the best thing in a case like this is to push on.

There’ll be some ugly talk for a while. That’s only

natural. But I’m sure you’ll manage. Won’t he,

Terry?” The Lemur nodded. “Yes, sir. Like riding a

horse.”

“Exactly,” Cocksedge said. “You have to get back

on and forge ahead. All this mooning about will only serve to raise

more questions.”

“And nobody wants that,” the Lemur said. “Do

they, Lyman?”

“No, sir.”

“Good. Then we’re all agreed,” Cocksedge

said.

“The first thing to do is put you on another case. You were

on that Pontevecchio suicide last year, weren’t you? That

Italian banker who hanged himself off Blackfriars

Bridge.”

“Not exactly, sir. I heard that I might be assigned, but the

inquest was closed by the time the official word came

through.”

“Of course. Well, some silly judge has reopened the case and

he’s given us another inning. Apparently he thinks the

inquest was closed too soon. Terry has the details. He’ll

give you the files. And you might want to have a chat with Hadley

too, if you can pry him loose from his damn garden. Hadley was the

one in charge. Did a fine job, if you ask me. But of course, no one

does.”

“Yes, sir.” Lyman began to move back toward the

door.

“By the way,” Cocksedge added. “You speak

Italian, don’t you?”

Lyman looked surprised. “No, sir. Some French. My mother was

from Brittany.”

“Quite. I knew it was a Romance. Well, brush up on your

damned Italian. You may need it. That’ll be all.” The

Lemur opened the door and Lyman started out, his head in a spin. He

barely saw the sour face Mrs. Clanger made as he walked by. The

lift arrived and he stepped in like a sleepwalker, the Lemur

pulling up the rear.

“Saved again, eh, Nigel?” the Lemur said.

“Don’t tell me I have you to thank.”

“Not likely. If there’s anyone to thank, I suppose

it’s the famous College Killer. Without him you’d have

never made the telly.”

“What are you driving at, Randall?”

The Lemur leaned against the wall, his hands knotted in the pockets

of his brown wool suit. “You’re a bit thick these days,

aren’t you, Lyman?” he said. “That’s the

odd thing about the telly. When you’ve been on once, you

bloody near belong to it. But it wouldn’t do if this Crosley

business got about. The whole department would go on

trial—not just you. You’re a symbol, Lyman. God help

us, but you are. The people picked you. And the people never make

mistakes.”

The lift opened with a creak and the Lemur started toward his

office, his narrow shoulders bouncing as he walked.

Lyman moved slowly in his wake, trying to raise some passionate

conviction, some righteous indignation, but his anger languished

deep inside him, countered by the fear he felt, the certainty that

the Lemur’s sharp appraisal had been absolutely true. He had

become a symbol. But of what? The dubious detective inspector? The

coward who had failed to listen when a fellow constable but half

his age had cried out for the shot, had shrieked for it?

“Shoot, Nigel. Bloody shoot!” Yet what if he had

missed?

He hastened down the corridor and as he stepped into the

Lemur’s tiny office, all he could think of was the ending of

another poem Chief Superintendent Cocksedge often quoted. It was by

Wilfred Owen, a writer Lyman favored to Sassoon, and it concerned

the meeting of two foot soldiers in hell, two symbols of the First

World War.

“I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark; for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now . . .”

Chapter Two

LONDON

August 10th, 1991

THE LEMUR’S OFFICE WAS ONLY HALF THE SIZE OF THE chief

superintendent’s, yet to Lyman it appeared much larger. The

walls were barren except for one small window and a dryboard made

of light gray plastic on which the superintendent had imposed a

cobweb of black lines, columns of names and numbers inscrutably

attached to projects and assignments. A PC purred upon his desk. A

telephone kept it company. There was nothing else, except for two

tan imitation leather chairs, one just the slightest bit more

padded than the other. The Lemur was already slipping into

it.

“What do you know about banking?” the superintendent

asked.

“I generally use postal orders myself.”

“I don’t mean banks. I mean banking, finance.”

Lyman did not answer. The Lemur was barking through the telephone.

“Pontevecchio, yes,” he said covering the mouthpiece

and raising his eyebrows.

“Yes, all of them.” He hung up.

“Precious little, I’m afraid.”

A moment passed and a chubby girl with an armful of files appeared

at the door. The Lemur motioned her forward and she slipped them

carefully onto his desk. Lyman recognized her. She was one of Dotty

Taylor’s friends. He had seen them sharing lunch in the

Wimpy’s down the road.

The Lemur plucked a file of photographs from the pile on his desk,

and tossed it to Lyman. “I’ll make this simple for

you,” he said. “There were three central players in

this clever little game.” He pointed to the foremost snapshot

in the file. “That first fellow with the rope about his neck

is Salvatore Pontevecchio.” Lyman stared down at the

photograph, wondering at the way the head was squeezed off to the

side. “I remember the newspaper stories.”

“Yes, but one can’t always believe what one reads in

the press.”

In the beginning, Lyman had thought the Lemur’s little barbs

were cast for his exclusive pleasure. They weren’t, of

course. Randall made a religion of alienation. He did it to

everyone who could not help him by the way. He always had.

“I personally believe the blighter hanged himself,” the

Lemur added with uncharacteristic candor. “In my opinion, the

man was done for and he knew it. The file is comprehensive. I

looked it over again this morning.

“Suffice it to say, Salvatore Pontevecchio was the chairman

of one of the largest private banks in Italy, Banco Fabiano. By

using his position at Fabiano, he was able to misappropriate vast

sums of money from the numerous financial institutions he

controlled in Italy, and then transfer them illegally to a motley

collection of paper companies in such tax havens as Luxembourg and

the Bahamas. Chinese boxes, really. For added secrecy and

protection he often used the Istituto per le Opere di Religione,

commonly called the IOR or Vatican Bank, as a financial conduit to

smuggle the cash out of the country. The Vatican is considered an

independent state within Italy, you see, with its own laws and

regulations.

“The head of the Vatican Bank at that time was—and

still is, presumably through divine intervention—gentleman

number two: Archbishop Kazimierz Grabowski. The banker Pontevecchio

acted as economic advisor to Archbishop Grabowski. In exchange for

providing the Church with financial insights and spectacular

profits, Pontevecchio obtained the secrecy of the sottane

nere, the black cassocks of the Vatican.”

“A blind eye,” Lyman volunteered. He looked down at the

photograph of the archbishop. Grabowski was a big man. He was

standing in the street before a crowd, wearing a dark business suit

and clerical collar, his arms extended as if to hold the people

back, his head bowed, his eyes glaring at the camera.

“Eventually,” the Lemur continued, “the money

which Salvatore Pontevecchio had transferred illegally through the

Vatican Bank made its circuitous way back to Italy. Usually it was

then spent in speculation on the Milan stock market, or invested in

arms and narcotics. Pontevecchio and Archbishop Grabowski both made

money, at least in the beginning. It was easy for them to predict

when a company’s shares were on the rise because they were

the ones driving the prices up, through their shell firms overseas.

Of course they had some help. To secure his position on the Banco

Fabiano board, and to protect himself politically, Pontevecchio

sought the assistance of the third and final player on our list:

Marco Scarcella.” The Lemur glanced at his watch.

“Christ,” he said. “Look at the

time.”

Lyman stared at the puffy round face of the balding gentleman in

the photograph before him. Marco Scarcella wore a pair of black

plastic spectacles. His eyes were small but full of life,

twinkling—like the eyes they always gave to Father Christmas

on those family cartoons.

The Lemur fiddled with his papers. “Let’s see,”

he said. “Marco Scarcella. Born in Pritoie, Italy. In 1936 he

went to Spain as one of Mussolini’s Black Shirts. Saw some

action in Albania. Then he fought against the Allies in Italy,

1943, as an SS Oberleutnant. After the war, he made his

way to Argentina, where he resurfaced as a senior executive of the

Perma Mattress Company. In addition to selling mattresses,

Scarcella also formed a rat line for escaped Nazis and eventually

became a kind of freelance national security consultant.” The

Lemur looked up and smiled. “Not your average Soho slasher,

eh, Lyman?”

“No, sir,” Inspector Lyman answered glumly.

“Are you following all this? Stop me if I go too

fast.”

“I’ll manage,” Lyman said. “Marco

Scarcella. Born in Pritoie, Italy. Fought in Albania. Smuggled

Nazis to Argentina.”

“Very good.” The Lemur thrust his jaw out

further.

“Scarcella was soon befriended by the great Juan Perón

himself. The Argentine dictator was so impressed that he later

granted the mattress salesman citizenship, and in the seventies

made him one of the country’s official economic

advisors.”

“What were his duties?”

“Import-export. Balance of trade. You know. Guns and

butter.”

Lyman sat up in his chair. The dull fatigue which had settled on

him at the beginning of the briefing suddenly fell away. The

seventies, he thought. Before the Falklands war. Guns and

butter.

The Lemur continued his narration. “Eventually Scarcella

returned to Italy, buying a villa in Tuscany with his savings.

According to Interpol, he appeared to have retired. But it was

precisely at this time that he began to construct a political and

financial organization which eventually amounted to a kind of

statewithin-a-state. Working under the guise of a secret Masonic

Lodge, Scarcella recruited members from the Italian military and

industry, journalists and politicians, anyone of power he could

influence. The lodge was called the I Four,

or—ironically—the IQ. It stood for Informazione

Quattro.

“Every country has its Freemasons,” Randall added with

disdain. “Even this one, I’m afraid. Of course

they’re usually fairly social things, business clubs with a

little mumbo jumbo in between to make everyone feel like they

belong to something.”

“I had an uncle who was one.”

“Indeed. I’m not surprised. But the I Four, Lyman, was

quite unique. Although the Italian postwar constitution

specifically prohibits secret societies, Scarcella took this

dormant pseudo-lodge and resurrected it. According to former

members, he dispensed with most of the normal, arcane rites and

bestowed upon himself extraordinary powers as the lodge’s

Venerable Master. Until it was exposed, Scarcella alone knew the

entire membership. Very exclusive. One was asked to join. In

exchange for the shortcut to money and power it provided, Scarcella

demanded information—something so delicate that it would

ensure the member’s loyalty, his silence.”

“Very neat.”

“Yes, very. Of course, not everyone cooperated. There’s

one report in the file which concerns a Roman magistrate who was

persuaded by his local priest to abandon the I Four and testify

against Scarcella and the rest. Two days before the trial, the

magistrate’s youngest daughter—only twelve years

old—was kidnapped by a group of Scarcella’s men, one of

whom we later arrested. That’s how we got the story.”

The Lemur folded his fingers together under his chin, and leaned

closer to Lyman.

“According to the informant, they took the girl to a house

which they had rented near a town called Terracina, halfway between

Naples and Rome, on the coast. Not just any house, mind you.

Scarcella was very particular about these kinds of things. It had

to be in the suburbs. It could never be too close to a neighbor, in

case they heard the screams. But the walls had to be thin enough to

hear through.” The Lemur sighed.

“Well, they found the perfect place, apparently. As was his

practice, Scarcella went upstairs and locked himself in a bedroom.

He usually preferred a small room; never the master bedroom. His

men, meanwhile, took the girl into the bedroom next door, where

they proceeded to rape and sodomize her repeatedly for over an hour

until she lost consciousness. I’ll spare you the grim

details. I’m sure it will suffice if I tell you that the

leader of this crew had a peculiar talent with a razor.

“No one ever knew what Scarcella did by himself in the room

next door. Somehow or other, he always heard or sensed when his

victims were hovering near death, for he would suddenly appear in

the doorway. The report states he was impeccably dressed on these

occasions, and this night was no exception. Everyone stood aside

when he came in. Scarcella walked over to the bed where the girl

lay. She was barely conscious by this time. Conscious enough to be

afraid, though.

Conscious enough to cry out, apparently, as Scarcella pulled the

pin out of the rose he was sporting on his lapel. He just stood

there over her, the flower in one hand and that bloody straight pin

in the other, watching her cower on the bedsheets. Then he leaned

forward, turned the rose round in his fingers, and stuffed it into

her mouth, stem first, as if he were planting it inside her.

That’s all he did. He left immediately thereafter, and drove

straight back to Rome.”

The Lemur leaned back in his chair. “Needless to say, the

girl’s father, the magistrate, never testified, and Scarcella

was acquitted.

“It was just about this time that Scarcella recruited

Pontevecchio. Despite their different backgrounds, both men shared

a fascist sensibility, an inordinate fear of communism, and a

respect for secret power. In some ways, it was almost inevitable

that they should have become partners. They offered each other so

much.”

“What happened to the girl?”

“What’s that?”

“The girl, the one you were just talking about.”

“As I recall, she bled to death.” He shook his

head.

“Are you listening, Lyman? Pay attention, please! Marco

Scarcella delivered the I Four, his political protection, and his

close connection to several Latin American regimes. And in return

Pontevecchio supplied the money from Banco Fabiano, and the cover

of the IOR—the discreet banking services and protecting arms

of the good Archbishop Grabowski. Together the three men made

millions, secretly controlling both the Italian government and much

of the press, bribing or killing anyone who got in their way. It

was a marriage made in heaven, or almost, anyway.”

The Lemur began to stare out of the window. It was as if he thought

that Lyman needed just a few more seconds to compile the

information, like the computer on his desk.

“Two events,” the Lemur added suddenly, “brought

this unholy alliance to an end. The first was the exposure of

Scarcella’s I Four. And the second, the collapse of

Pontevecchio’s Banco Fabiano.

“In the spring of 1989,” he explained, “a French

suspect revealed that Scarcella had helped finance a heroin factory

near Florence, Italy. A detachment of guardia di finanza

was ordered to investigate, but by the time they arrived Scarcella

had already disappeared. Tipped off, I’m sure. They found

nothing in his Tuscan villa. But at the offices of the local Perma

Mattress factory, just a few miles away, they unearthed a list of

almost one thousand I Four members. In one day the secret Masonic

Lodge was stripped of its most powerful attraction—it

wasn’t secret any longer. Scarcella escaped to South

America.”

“Is that where he is now?” Lyman asked.

The Lemur raised an eyebrow. “No, thank God. He was spotted

in May last year, in France, one month before Pontevecchio was

found hanging from Blackfriars Bridge. But the French gendarmerie

let him get away. Then last September he flew to Switzerland, where

he was arrested trying to withdraw some fifty-five million dollars

from an account suspected of being connected to the Banco Fabiano

scandal. He’s tucked away in Champ Dollon prison now, near

Geneva. The chief superintendent wants you to try and arrange an

interview, but as far as I’m concerned, it probably

isn’t worth the ticket. Scarcella won’t talk to

anyone.”

“Is that so?”

“The collapse of Fabiano happened almost

simultaneously,” the Lemur added peevishly, “resulting

in the largest financial scandal in banking history. I don’t

remember all of the details. There are précis in the files,

newspaper clippings and the like. That’s your job,

anyway.”

He looked up. “But it was really just a matter of time for

Salvatore Pontevecchio. The financial hole at his Banco Fabiano

grew larger and larger, until one day there was no more money left

to transfer. Archbishop Grabowski pleaded ignorance, denying the

IOR’s responsibility, despite the fact that the companies in

which Pontevecchio had invested were owned primarily by the Church.

When the statements and bank papers were finally unraveled, it

appeared that the hundreds of millions of dollars embezzled from

Fabiano had simply disappeared.” The Lemur smiled

darkly.

“Pontevecchio had already been to jail during an earlier

scandal. It was there he tried to kill himself the first time. He

knew what it was like.”

Lyman looked down once again at the photograph of the Italian

banker, the bulging eyes, the skin puffed up around the nylon

noose. “So Pontevecchio fled to London, is that

it?”

“That’s right. In June, last year,” the Lemur

said.

“Where he tried to kill himself again, except that this time

he succeeded?”

“That’s what the inquest ruled, and I happen to agree.

For a change. It’s your job to see if it was something

else.”

“But why?”

“Why what?”

Lyman leaned forward in his chair, hunching his shoulders like the

pincers of a crab. “I mean, why not Brazil or Argentina? What

did Pontevecchio hope to gain in London?”

“Really, Lyman. Shall I lead you by the nose through all of

this? According to another Mason named Angelo Balducci—who

was his escort into London—Pontevecchio was trying to arrange

a meeting with the Opus Dei, a wealthy right-wing Catholic

group.”

“What for?”

“To save himself, presumably. To ask for absolution, for

money, for another chance. How should I know? Balducci was arrested

last year on charges of smuggling. But he claims he only helped

Pontevecchio get into the country, and he has a perfect

alibi.”

The superintendent began to reassemble the files before him.

“Pontevecchio’s wife, who’s now living in

America, reported that he telephoned her just before his death and

told her everything would be all right, that he had found something

wonderful and that Archbishop Grabowski would finally have to honor

his financial responsibilities. Pontevecchio was clearly on the

edge, and tilting. His bank had collapsed into that hole, now one

point three billion dollars wide. Scarcella would no longer protect

him. Pontevecchio was a public failure, exposed. They’d dug

him up, like a grub in a spadeful of earth, and he couldn’t

take the light.” The Lemur slapped the top file loudly.

“Justice, Lyman. What we’re paid to mete out, hard and

true.”

“I thought that was the courts’

prerogative.”

“Don’t get cheeky, Lyman. This is our second go on this

one, the second inning.”

Isn’t that what Cocksedge had called it, Lyman

thought—a second inning?

“Just do your standard plodding job of it and we’ll all

be friends again. We’ll leave young Crosley in the customary

files. Welcome aboard.”

The Lemur pushed the rest of the papers across the desk. Then he

picked up the telephone and swiveled his chair away. The briefing

was over.

Lyman eyed the superintendent closely. He did not feel offended by

the briefing’s sudden termination, but he was nettled by the

Lemur’s gracelessness. It would take little imagination to

force a conversation on his secretary, yet the superintendent sat

there without speaking, the receiver poised a fraction of an inch

from his perfect, tiny ear.

Lyman gathered up the files and headed out the door. The corridor

was filling up. It would be lunchtime soon and the world was

washing up, or making plans, or working through it once

again.

If Pontevecchio had died in some hotel, Lyman thought, in another

part of London, the case would have gone to Scotland Yard, to the

Metropolitan Police. But instead he’d hanged himself, or been

the victim of a murder, beneath Blackfriars Bridge. In the public

view. In that one square mile which marked the province of the City

of London Police. And yet the job seemed like a task best left to

Interpol. Lyman sighed. What did he know about Italian Masonry, or

finance for that matter? Why wasn’t the chief inspector in on

this one? The job demanded special skills.

Lyman pushed the button for the lift and wished himself back to the

Brass Monkey, the slow thick shadows of the pub which he had

frequented so often as a young policeman back in Hampshire. He

tried to visualize the glassy chalk stream of the River Itchen out

the window, balanced precariously on the backs of trout, the female

bulging of St. Catherine’s Hill, its Saxon ditch and rampart

gathering the errant trees into a single copse of green, the

ancient oaks and poplars rocking him to sleep a hundred feet above

the ground, curled like a question mark about the moving branches.

Sometimes he thought of going back to Winchester. But they had

built a motorway around the Hill, and half his family and friends

had died or moved away. There was little point in going back,

almost as little as in reminiscing.

The lift arrived and Lyman stepped in. It was nearly full. He

turned his back to the crowd. Someone was wearing a florid perfume.

It smelt like jasmine and Lyman thought about Dotty Taylor, the way

her thighs had come together at the top and formed a triangle of

light as she had walked away from him into the bathroom to wash up.

It had only been twelve nights, twelve nights and thirteen

days.

The doors creaked open once again, this time preceded by the

clapping of a hidden bell. A young woman bundled in a scarf and

raincoat stared expectantly into the lift. “Going

down?” she asked.

No one answered, and for a moment Lyman heard the question as if it

had been meant for him alone, a grim indictment of the last years

of his life. The doors closed just as suddenly and the woman in the

raincoat disappeared.

Dotty Taylor wasn’t what he needed, Lyman thought. Cocksedge

had been right. Work was the answer. He had to climb back on again,

but his hands were loath and cold.

THE DARK BLUE TR4 LUNGED ACROSS THE CROWDED motorway, trying to

force a space between a Jaguar and a two-ton lorry. Inside the car,

Lyman kept one hand on the wheel and the other on a tattered road

map in his lap. He had never been to this part of Surrey before,

but he knew the turn to Haslemere was fast approaching. Beside him,

his dead son’s mongrel, George, stood with his nose half out

the window, barking and chomping at the wind.

“Oh, for Christ’s sake, George, shut up.” Lyman

nudged him with his elbow but the animal remained transfixed. His

fur was knotted and thick, the color of day-old snow.

Part Corgi and part unknown, he had indecisive ears that drooped

and stood erect and drooped again as he sniffed the air outside the

window.

The road curved. Lyman passed another car, and found himself within

the current of a roundabout. The road signs seemed unnaturally

small, pointing at the oddest angles as if they had been turned by

vandals in the night. He glimpsed the one for Haslemere too late.

The tires of the Triumph squealed, George barked, and Lyman swung

the car around the roundabout again. It took him another twenty

minutes before he reached the country road which, according to his

map, would bring him to the house of former Superintendent Hadley.

The sun had disappeared behind a bank of clouds. A wind blew from

the west across the fields, bending the hedgerows, tilting the

trees. He passed a dairy farm and suddenly there it was, the lane

which Hadley had described that morning with punctilious

detail.

The house was nestled in a little valley lush with rhododendron

bushes. It was a large, neo-Tudor structure with bright white

plaster walls and heavy wooden crossbeams. Lyman pulled his car up

to the front and turned the motor off. At the rear of the house he

could see a conservatory, and beyond that a kind of sunken garden

full of rosebushes. He opened the door, mindful not to let the dog

out in his wake, and headed for the entrance.

The former superintendent appeared in the open doorway, his hand

extended in a greeting. “Nigel,” he said.

“It’s good to see you again. I was expecting you much

earlier.”

Lyman frowned. “Sorry, sir,” he said. “The roads

are absolutely jammed.”

“None of that now.”

“Pardon?”

“No more sirs and superintendents left for me. Given

all that up. It’s Squire Hadley now.” He laughed. Lyman

tried to smile.

“Just call me Tim. I was only joking, Lyman.”

“Yes, sir. Tim.” George barked from the car and Lyman

rolled his eyes. “Damn dog.”

“Well, let him out, man,” Hadley said as he bounded

from the entrance. He was a tall, broad-shouldered man with

thinning black hair and cavernous green eyes. He had been in an

auto accident as a child, and still carried the scars along his

cheeks—deep-set and knotted purple lines which made his face

seem more dramatic than grotesque. Perhaps it was the emerald eyes.

Or perhaps it was the smile, so china perfect. Hadley opened the

car door and George escaped with a growl.

“I was afraid he’d muck up your garden,” Lyman

said.

“Don’t be ridiculous. Good for the soil. You should see

how much I pay for dung each year.” Hadley looked up at the

sky. “Why don’t we walk for a bit,” he said.

“I’d invite you in but the Mrs. isn’t feeling up

to visitors.”

“Of course.”

Hadley grinned again and Lyman thought that it had been a long time

since he’d seen him smile that way. And there it was again,

twice in a day, in a moment. There had been a time once, Lyman

remembered, soon after his arrival on the force, when he and Hadley

had almost become friends. Hadley—then only a chief

inspector—had taken the country constable under his wing, at

first no doubt to share in the warm glow of the reporters’

cameras whenever they came to interview the man who had caught the

infamous College Killer. But after a while, the more they worked

together, the more they found they had in common. Hadley frequently

assigned the young inspector to his cases, tutoring him with care,

introducing him to his most reliable informers. And so it was that

in the first year of his tenure with the City of London Police,

Lyman solved more crimes than anyone of his rank in the history of

the department.

Then something happened that Lyman had never really understood.

Hadley was promoted to superintendent, and almost overnight he

withdrew from everyone with whom he had hitherto shared his life,

including Lyman. It was as if the previous years had only been a

preparation for this inevitable ascension. He joined a different

set of clubs. He bought a bigger car. He moved into another flat,

in a different part of town. He met the woman who would soon be

Mrs. Hadley. “Butterflies don’t mix with

caterpillars,” they said around the office.

Five months later Hadley was assigned to the Pontevecchio case. And

then, upon completion of the inquest, the brand-new superintendent

astounded everyone with the news that he was going to retire, ten

years before his time. His wife had come into some money, it was

said, and he planned to buy a house in Surrey and raise

flowers.

Others were less kind, insisting that the superintendent had been

sacked, the victim of a power play with Cocksedge. Informal parties

were arranged to bid him bon voyage. Lyman had attended these

religiously, but each time he had tried to tell the superintendent

what a debt of gratitude he felt, Hadley had only shaken his head

and pulled away.

In a few weeks, Hadley was forgotten practically by everyone. It

was his job now that concerned them, the struggle to fill the

impending vacuum. Some said the Lemur was the obvious replacement.

After all, Randall had seniority, and a fine record of arrests. But

he was not well liked. Others insisted Lyman had a chance.

In truth, Lyman had never really cared about the race. He liked his

job just as it was, and he did not fancy the idea of spending his

career behind a desk on the fifth floor. So when he finally heard

the news of Randall’s imminent promotion, he felt relieved

that he had not been chosen, although one thing distressed him.

They said that the deciding vote against him had been cast by

Superintendent Hadley; it was his last official act.

Lyman and Hadley crossed the driveway and headed round the house

toward the conservatory. Neither of them had spoken for several

minutes when suddenly Hadley said, “So what exactly do you

want to know, about the case I mean?”

Lyman was looking at a bed of heather. The lavender branches were

thick with tiny spines. “I thought perhaps that you might . .

. I don’t know, fill in the empty spaces.”

“What did Brian tell you?”

“Not much. Randall briefed me.”

“And?”

“And what?”

“Your findings. Your results, man. Your analysis. Was it a

suicide or wasn’t it?”

“I have no idea. I’ve only just begun.” Hadley

nodded grimly. “I see. Yes, well, I suppose that’s

sensible. You’d want to go in with an open mind and all that.

Only natural. Who are your prime suspects then, if I may

ask?”

Lyman shrugged. “Archbishop Kazimierz Grabowski, I suppose.

And Marco Scarcella too.”

“Scarcella’s in prison, in Switzerland. And he’s

an old man now.”

“Yes, so I heard. But he wasn’t in prison when

Pontevecchio died, in June last year. The Lemur told me Scarcella

was spotted in France in May, right before Pontevecchio’s

death. But it wasn’t until September that they arrested him

in Switzerland.”

“Here, let me show you something,” Hadley said

abruptly. He drew his hands together behind his back and hastened

down the path toward the conservatory. Lyman followed.

“Are you a collector, Lyman?” Hadley said, as he

fiddled with the door.

“Sir?”

“Stamps, coins—that sort of thing.”

“Oh, I see.” The glass door opened and Lyman felt a

wall of warm moist air surround him. “Not

really.”

“Pity,” Hadley said. “I think it gives a man

something, especially when he retires. Don’t delay,

Lyman.

You’ll soon be on the ash heap too. Find something, anything.

Something to do. Something to hold on to.”

He strode forward. Lyman could see the racks and racks of

vegetation on the walls around them, thick flowers hanging down, a

drape of color on the heavy air. “Something to look

after,” Hadley continued.

“Shut the door.”

Lyman stepped in.

“Orchids have always been my fancy,” Hadley said.

“I think it’s because they’re so vital, so

organic. Not like the job, eh?” He picked up a leafless

spray. The flowers were creamy white, suspended from a piece of

corkboard on the wall. “Ghost orchids,” he said. Lyman

examined a clot of leaves and petals near the door. The flowers

looked like open wounds, fleshy and exposed. Where was the soil, he

wondered, or did they simply grow that way? “Very nice,

yes.”

“Take a look at this one.” The superintendent pointed

at another plant with verdant, palmlike leaves. A spike of flowers

hung down to one side. The plant was festooned with two-inch

blossoms, pale green with light brown tips, spoon-shaped and hooded

like a line of monks on their way to morning prayers.

“It’s a Catasetum trulla,” Hadley said.

“A friend of mine imports them from South America.

Isn’t it lovely? They have the oddest reproductive

cycle.” He poked a fingertip into a blossom. “See?

Their stamens are buried so deep within them that over the

millennia they’ve developed a kind of alkaloid which makes

the bees that pollinate them drowsy. The bees fall in, you see,

drunk on the nectar, and cover themselves with pollen. Some

orchidologists believe the insects actually remember, returning

again and again just for the drug.”

“Fascinating,” Lyman said. “About the case . .

.”

“Yes, yes, the case. Well, if it wasn’t

suicide,”

Hadley said, “then I’d put my money on

Grabowski.” “The archbishop? Why?”

“I met His Excellency in Rome. It was during the first

inquest.”

“What was he like?”

“Canadian. Big bloke. Six foot three at least. Sixteen stone.

He used to play ice hockey as a boy. I suppose that’s why

Pope Paul employed him as a kind of unofficial bodyguard. But he

didn’t have any time for us.

He kept on saying how busy he was, how he was doing us such a big

bloody favor just by seeing me. Meanwhile, all I could think of was

how I knew he was born in this hovel in Toronto, on the wrong side

of town. His parents were Polish, right off the bloody boat. I mean

real wogs. The only reason he even went to university was because

he was a priest.”

“Why would he have killed Pontevecchio?”

“It’s obvious, isn’t it? He wanted to cover up

the Vatican Bank’s connection with Banco Fabiano after the

scandal broke. Don’t think—just because he’s a

priest—that he couldn’t have done it. Believe you me.

He may be an archbishop, but Grabowski is no saint. He’s a

banker through and through.”

Lyman nodded glumly, remembering the file on the archbishop. But at

some point, he considered, at some time Grabowski must have

honestly believed. In seminary perhaps, or as a parish priest in

west Ontario.

How strange, Lyman thought, that a man of God should have become a

banker in the end, trading as much in numbers, in proven formulae,

as in the intangibles of faith. “I suppose so,” he said

at last. “Then you think he knew Pontevecchio was embezzling

from Banco Fabiano.”

“He must have. They were using the Vatican Bank to get the

money from Fabiano out of Italy. The government was cracking down

on taxes and the Church was desperate to account for the missing

funds. He was desperate.”

Suddenly George began to bark. Lyman looked up. The dog was playing

in the sunken garden, chasing birds.

“Of course,” Hadley added softly, “that’s

only my opinion. It’s your case now, and I wouldn’t

want to influence you one way or the other.”

“Of course.” George barked again and Lyman watched in

horror as the dog began to dig around a rosebush.

“Sorry,” he said, dashing toward the door. He swung it

open, shouting, “George. George, stop that.” The dog

looked up momentarily, his paws half buried in the ground.

Lyman shut the door behind him and walked around the conservatory.

“Come here,” he said. “Come here this

instant.”

The dog trotted over. Lyman raised a hand to strike him, but at the

last moment he felt his anger falter. “That’s no

way,” Hadley said behind him. “You’ve got to

discipline them. You’ve got to let them know who’s the

master.”

“Yes, I know,” Lyman said. “It’s just that

when he looks up at me . . .” He could not finish.

“Spare the rod. You know what they say.”

“He’s really my son’s dog. Or was. I’m not

very good with animals.”

They both glanced down at George. Then Hadley said, “I was

sorry to hear about young Crosley, Nigel. He was a good

policeman.”

Lyman nodded.

“Try not to take it personally. I’m sure it

wasn’t your fault. I’m sure you did everything you

could, by the book.”

“By the book,” Lyman repeated.

“Let me give you a piece of advice, Nigel. You’ve had a

hard time of it lately. I’d take this Pontevecchio case

slowly, if I were you. Work back into things. Don’t push

yourself. It’s really only a formality anyway.” He

looked back at the conservatory. “Was there anything else you

wanted?”

“Actually, I did have some questions about

Scarcella.”

“Yes, of course. Scarcella. I only ask because I have to

drive the Mrs. up to Guildford. It’s the music festival next

week and—well, you know—she just has to have

her hair done.” Hadley looked down at his watch.

“You should come out again sometime. Soon.”

“Thank you, I will. But, about Scarcella—”

“The bastard’s already in prison, where he belongs. I

doubt if I can tell you anything you haven’t read in the

files. Sorry I couldn’t be of any further help. Strange,

isn’t it? It’s only been a year since

Pontevecchio’s suicide and yet it seems so far away. Another

lifetime. I hope we get to see you again. I mean that,

Nigel.”

“Thanks very much. Another time then. I’ll ring

you.” Lyman patted George on the head. “It was good to

see you again.”

They shook hands, and started toward the driveway at the front of

the house. When they reached the car, Lyman opened the passenger

door and George jumped in without a fuss. “Well, thanks

again,” Lyman said, searching for his keys. “I liked

your flowers.”

“Think about what I said. Find a hobby. Don’t put it

off. None of us is getting any younger.”

“Yes. Yes, I know,” Lyman said, ducking into the

car.

“And Nigel . . .”

Lyman looked up through the window.

“Yes, sir?”

“I wasn’t sacked, you know. Just to set the record

straight.”

“I never thought you were.”

“No, you wouldn’t, would you. Not Nigel

Lyman.”

Hadley smiled sadly. “I made a lot of mistakes in my career,

Nigel, but leaving the department wasn’t one of

them.”

Hadley backed off toward the entrance of the house. Lyman turned

the ignition key. The motor coughed like a sleeping child, and

caught.

It had been a pointless exercise, Lyman thought, a waste of time.

He had learned precious little about Pontevecchio, and even less

about Scarcella. He headed down the drive, turning only once to

catch a glimpse of Hadley in the rearview mirror throwing a

heartless wave into the air. Then he was gone.

Lyman drove along the country road, trying to think of something

other than his case, trying to forget himself within the constant

uniformity of the dividing line. Black, white, black. He thought

about Tim Hadley, about his orchids and the way their slender roots

had dangled in the air, thirsty for moisture.

Hadley had done all right for himself with his collecting,

especially for a policeman. A posh house and a garden, a wife with

a taste for music festivals. No wonder he’d retired

early.

The road narrowed up ahead and George began to bark once again,

lunging at the window. “Quiet,” Lyman said.

“Please, George.” He slowed the car. They were crossing

a bridge. On the river far below, a solitary sculler cut the

waterway in half, pulling at his wooden blades, gliding on the

surface through the reeds.

Excerpted from GOSPEL TRUTHS © Copyright 2011 by J.G.

Sandom. Reprinted with permission by Bantam, a division of Random

House. All rights reserved.

Gospel Truths

- Genres: Nonfiction, Religion

- Mass Market Paperback: 432 pages

- Publisher: Bantam

- ISBN-10: 0553589792

- ISBN-13: 9780553589795