Excerpt

Excerpt

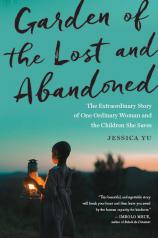

Garden of the Lost and Abandoned: The Extraordinary Story of One Ordinary Woman and the Children She Saves

The Thirsty Baby

The bottle of water sat on Officer Harriet’s desk, its contents clear, its slightly crumpled label depicting the ice-capped Rwenzori Mountains. In spite of the heat, the policewoman and the reporter looked upon it not with thirst but with suspicion.

It was Monday at Kawempe CPU — Child and Family Protection Unit — and the two women had a sick baby, a missing mother, and a clue.

A nine-month-old boy, naked and feverish, had been brought to a clinic by his mother. She reported his name as Brasio Seguyo. The nurses diagnosed malaria and put the baby on an IV drip. The mother paid a small deposit on the treatment fee, saying she would come back with the rest of the money. Two days later, she had not returned. Only the bottle of water had been delivered, with a note saying it was for the baby. The plastic cap had clearly been twisted open; the seal on its neck was absent.

The baby in question lay draped over Officer Harriet’s shoulder, his body as limp as a warm chapati. Lacking boys’ clothes, the clinic had sent him to the police in a blue-and-pink-flowered dress, its bottom now damp-dark from a diaper worn overnight. Harriet flipped through a report folder, expertly avoiding the wet spot as she supported the baby with her other arm.

Harriet Nantaba was one of Gladys’s favorite officers. It was easy for CPU officers to become overwhelmed by the daily flood of domestic disputes and abuse cases, but Harriet could always be counted on to gather the Who, What, Where, and When that Gladys needed for her newspaper column about lost children. In addition to being efficient, Harriet was always neatly groomed, her olive-green uniform perfectly fitted — a modern vision of a young policewoman. Children in particular seemed to like her, perhaps because Harriet was also pretty, her classic features offset only by a disarming gap-toothed smile.

“Did the nurses give the baby the water?” Gladys asked.

“I don’t know. That’s how they brought it. They said they feared —”

“— it may contain something.”

“Yes,” said Harriet. “It could be contaminated. Maybe the mother wanted to have the baby killed or something like that. So this is an exhibit now for police.”

“Yes, we are holding it as an exhibit.”

“Hmm.”

Their eyes locked on the bottled water. They sweated and stared, the heat swelling with the silence. The CPU was always hot.

While Kawempe Police Station was a proper building, with two stories and a parking area for motorbikes in the front, its Child and Family Protection Unit was an eight-by-twenty-foot shipping container donated by a Finnish NGO. Plunked down on a dirt lot next to an ever-smoldering trash pile, the metal box housed two desks, two sets of bookshelves, four wooden benches, half a dozen plastic chairs, and frequently the maximum seating capacity of bodies. Two small windows provided air but no cross breeze, as they were cut into the same side of the wall. Under the steady glare of the Kampala sun, the steel walls that provided the material fortitude for stacking on a cargo ship became an oven.

Gladys noticed that while she and Harriet sweated, the baby did not. His forehead had the dull surface of a stone. “He’s very dehydrated,” she remarked.

“We tried to give him some juice, but he vomited.”

Gladys shook her head. “He looks really, really, bad off.”

“He needs the drip treatment. He only got a little bit.” Harriet explained that when Brasio’s mother had not shown up with the money, the baby had been taken off the IV. “The clinic realized no one is coming to claim for the child, so they stopped treatment.”

“He didn’t get a full dose.”

“No, of course, he couldn’t. Because there was no one to pay.”

Gladys sighed. “Now, Harriet, I know we need profits for our businesses. But in such cases, can’t someone sympathize with a baby like this and complete the dose?”

Harriet demurred. “I’m not very sure . . .”

“O-kay,” Gladys said, steering away from the dead end of the rhetorical. She flipped to a clean page. “And what was the name of this clinic?”

“Family Hope Clinic.” The irony escaped the room like an unswatted mosquito.

Outside, the sun shone directly on the wilted line of supplicants sitting in front of the shipping container, and grumbling voices rose up to its tiny windows. Gladys frowned down at her notebook, weighing the possible outcomes of including Brasio’s story in her column. Would the mother come forward? If she did, could the police analyze the contents of the mysterious bottle of water? What if she was not sane? They could not release the child to a mother who intended to poison him. But perhaps another family member would recognize Brasio and come forward to claim him.

As she readied her camera, Gladys wished they had boy’s clothes to put Brasio in, so as to avoid any doubts planted by the flowered dress.

“Hold him up so I can see his face,” she directed Harriet.

Harriet lifted Brasio away from her shoulder and turned him toward Gladys. The boy’s eyes fluttered open, and the sight of the water bottle on the desk momentarily energized him. He moaned and thrust out an unsteady arm.

“Ah, ah,” Harriet soothed.

Gladys snapped photos as the baby pined for the water; she needed a clear look at his face. It felt bad not to reward him with a drink, but there was nothing else to offer. Given their low wages, police did not have money for amenities like bottled water.

“I wish you could remove that bottle from there,” Gladys said.

Harriet gingerly relocated the exhibit to a stack of boxes by the wall.

“Good,” said Gladys. “I’m worried that someone may feel thirsty and pick it up.”

“It is me. It is me who is thirsty.” Harriet laughed, showing the friendly gap in her teeth.

Gladys sighed. Everybody was thirsty.

After a few phone calls, Gladys enlisted a social worker to help her deliver Brasio to St. Catherine’s Clinic. There the infant drifted in and out of consciousness, failing to stir even when the nurse pricked his fingers for a blood sample. Gladys had endured malaria many times, and she knew the crushing, invisible weight the disease placed on the will as well as the body. This body, limp as a doll’s, looked spent, and there was little sign of will. Who could say whether the child was still clinging to this life or it was only the hands of others detaining him a few moments longer?

If the doctor knew, his mild expression gave nothing away. Gladys lingered by the examining table as he gently prodded Brasio’s swollen belly. “I’m worried about that stomach,” she murmured.

The doctor did not think the swelling was due to malaria. “It’s probably malnutrition.”

“Ah.” Gladys nodded, unsure if that was good news.

The doctor moved to the head of the table, and Gladys now saw that Brasio’s eyes were half open, revealing only empty white crescents. The sight froze her in place. How could she leave, with the baby looking so much worse than when she had first seen him?

“Thank you for these good works,” she managed, by way of farewell. “For my abandoned babies.”

The doctor’s nod answered her unspoken question. Only time would tell.

Garden of the Lost and Abandoned: The Extraordinary Story of One Ordinary Woman and the Children She Saves

- Genres: Biography, Nonfiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Mariner Books

- ISBN-10: 1328500187

- ISBN-13: 9781328500182