Excerpt

Excerpt

Friends, Lovers, Chocolate: The Sunday Philosophy Club

Chapter one

The man in the brown Harris tweed overcoat --- double-breasted with

three small leather-covered buttons on the cuffs --- made his way

slowly along the street that led down the spine of Edinburgh. He

was aware of the seagulls which had drifted in from the shore and

which were swooping down onto the cobblestones, picking up

fragments dropped by somebody who had been careless with a fish.

Their mews were the loudest sound in the street at that moment, as

there was little traffic and the city was unusually quiet. It was

October, it was mid-morning, and there were few people about. A boy

on the other side of the road, scruffy and tousle-haired, was

leading a dog along with a makeshift leash --- a length of string.

The dog, a small Scottish terrier, seemed unwilling to follow the

boy and glanced for a moment at the man as if imploring him to

intervene to stop the tugging and the pulling. There must be a

saint for such dogs, thought the man; a saint for such dogs in

their small prisons.

The man reached the St. Mary's Street crossroads. On the corner on

his right was a pub, the World's End, a place of resort for

fiddlers and singers; on his left, Jeffrey Street curved round and

dipped under the great arch of the North Bridge. Through the gap in

the buildings, he could see the flags on top of the Balmoral Hotel:

the white-on-blue cross of the Saltire, the Scottish flag, the

familiar diagonal stripes of the Union Jack. There was a stiff

breeze from the north, from Fife, which made the flags stand out

from their poles with pride, like the flags on the prow of a ship

ploughing into the wind. And that, he thought, was what Scotland

was like: a small vessel pointed out to sea, a small vessel

buffeted by the wind.

He crossed the street and continued down the hill. He walked past a

fishmonger, with its gilt fish sign suspended over the street, and

the entrance to a close, one of those small stone passages that ran

off the street underneath the tenements. And then he was where he

wanted to be, outside the Canongate Kirk, the high-gabled church

set just a few paces off the High Street. At the top of the gable,

stark against the light blue of the sky, the arms of the kirk, a

stag's antlers, gilded, against the background of a similarly

golden cross.

He entered the gate and looked up. One might be in Holland, he

thought, with that gable; but there were too many reminders of

Scotland --- the wind, the sky, the grey stone. And there was what

he had come to see, the stone which he visited every year on this

day, this day when the poet had died at the age of twenty-four. He

walked across the grass towards the stone, its shape reflecting the

gable of the kirk, its lettering still clear after two hundred

years. Robert Burns himself had paid for this stone to be erected,

in homage to his brother in the muse, and had written the lines of

its inscription: This simple stone directs Pale Scotia's way/To

pour her sorrows o'er her poet's dust.

He stood quite still. There were others who could be visited here.

Adam Smith, whose days had been filled with thoughts of markets and

economics and who had coined an entire science, had his stone here,

more impressive than this, more ornate; but this was the one that

made one weep.

He reached into a pocket of his overcoat and took out a small black

notebook of the sort that used to advertise itself as waterproof.

Opening it, he read the lines that he had written out himself,

copied from a collection of Robert Garioch's poems. He read aloud,

but in a low voice, although there was nobody present save for him

and the dead:

Canongait kirkyaird in the failing year

Is auld and grey, the wee roseirs are bare,

Five gulls leem white agin the dirty air.

Why are they here? There's naething for them here

Why are we here oursels?

Yes, he thought. Why am I here myself? Because I admire this man,

this Robert Fergusson, who wrote such beautiful words in the few

years given him, and because at least somebody should remember and

come here on this day each year. And this, he told himself, was the

last time that he would be able to do this. This was his final

visit. If their predictions were correct, and unless something

turned up, which he thought was unlikely, this was the last of his

pilgrimages.

He looked down at his notebook again. He continued to read out

loud. The chiselled Scots words were taken up by the wind and

carried away:

Strang, present dool

Ruggs at my hairt. Lichtlie this gin ye daur:

Here Robert Burns knelt and kissed the mool.

Strong, present sorrow

Tugs at my heart. Treat this lightly if you dare:

Here Robert Burns knelt and kissed the soil.

He took a step back. There was nobody there to observe the tears

which had come to his eyes, but he wiped them away in

embarrassment. Strang, present dool. Yes. And then he nodded

towards the stone and turned round, and that was when the woman

came running up the path. He saw her almost trip as the heel of a

shoe caught in a crack between two paving stones, and he cried out.

But she recovered herself and came on towards him, waving her

hands.

"Ian. Ian." She was breathless. And he knew immediately what news

she had brought him, and he looked at her gravely. She said, "Yes."

And then she smiled, and leant forward to embrace him.

"When?" he asked, stuffing the notebook back into his pocket.

"Right away," she said. "Now. Right now. They'll take you down

there straightaway."

They began to walk back along the path, away from the stone. He had

been warned not to run, and could not, as he would rapidly become

breathless. But he could walk quite fast on the flat, and they were

soon back at the gate to the kirk, where the black taxi was

waiting, ready to take them.

"Whatever happens," he said as they climbed into the taxi, "come

back to this place for me. It's the one thing I do every year. On

this day."

"You'll be back next year," she said, reaching out to take his

hand.

On the other side of Edinburgh, in another season, Cat, an

attractive young woman in her mid-twenties, stood at Isabel

Dalhousie's front door, her finger poised over the bell. She gazed

at the stonework. She noticed that in parts the discoloration was

becoming more pronounced. Above the triangular gable of her aunt's

bedroom window, the stone was flaking slightly, and a patch had

fallen off here and there, like a ripened scab, exposing fresh skin

below. This slow decline had its own charms; a house, like anything

else, should not be denied the dignity of natural ageing --- within

reason, of course.

For the most part, the house was in good order; a discreet and

sympathetic house, in spite of its size. And it was known, too, for

its hospitality. Everyone who called there --- irrespective of

their mission --- would be courteously received and offered, if the

time was appropriate, a glass of dry white wine in spring and

summer and red in autumn and winter. They would then be listened

to, again with courtesy, for Isabel believed in giv- ing moral

attention to everyone. This made her profoundly egalitarian, though

not in the non-discriminating sense of many contemporary

egalitarians, who sometimes ignore the real moral differences

between people (good and evil are not the same, Isabel would say).

She felt uncomfortable with moral relativists and their penchant

for non-judgementalism. But of course we must be judgemental, she

said, when there is something to be judged.

Isabel had studied philosophy and had a part-time job as general

editor of the Review of Applied Ethics. It was not a demanding job

in terms of the time it required, and it was badly paid; in fact,

at Isabel's own suggestion, rising production costs had been partly

offset by a cut in her own salary. Not that payment mattered; her

share of the Louisiana and Gulf Land Company, left to her by her

mother --- her sainted American mother, as she called her ---

provided more than she could possibly need. Isabel was, in fact,

wealthy, although that was a word that she did not like to use,

especially of herself. She was indifferent to material wealth,

although she was attentive to what she described, with

characteristic modesty, as her minor projects of giving (which were

actually very generous).

"And what are these projects?" Cat had once asked.

Isabel looked embarrassed. "Charitable ones, I suppose. Or

eleemosynary if you prefer long words. Nice word that ---

eleemosynary . . . But I don't normally talk about it."

Cat frowned. There were things about her aunt that puzzled her. If

one gave to charity, then why not mention it?

"One must be discreet," Isabel continued. She was not one for

circumlocution, but she believed that one should never refer to

one's own good works. A good work, once drawn at- tention to by its

author, inevitably became an exercise in self-congratulation. That

was what was wrong with the lists of names of donors in the opera

programmes. Would they have given if their generosity was not going

to be recorded in the programme? Isabel thought that in many cases

they would not. Of course, if the only way one could raise money

for the arts was through appealing to vanity, then it was probably

worth doing. But her own name never appeared in such lists, a fact

which had not gone unnoticed in Edinburgh.

"She's mean," whispered some. "She gives nothing away."

They were wrong, of course, as the uncharitable so often are. In

one year, Isabel, unrecorded by name in any programme and amongst

numerous other donations, had given eight thousand pounds to

Scottish Opera: three thousand towards a production of Hansel and

Gretel, and five thousand to help secure a fine Italian tenor for a

Cavalleria Rusticana performed in the ill-fitting costumes of

nineteen-thirties Italy, complete with brown-shirted Fascisti in

the chorus.

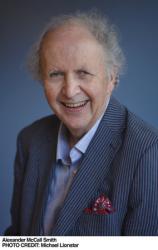

Excerpted from FRIENDS, LOVERS, CHOCOLATE © Copyright 2005

by Alexander McCall Smith. Reprinted with permission by Pantheon, a

division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.