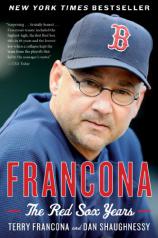

Francona: The Red Sox Years

Review

Francona: The Red Sox Years

The old sports saying goes that managers are hired to be fired. Regardless of one’s success, there will always be a time when a lack of production, a scandal, or just plain bad luck will lead to the dismissal of a team’s leader, regardless of what a good guy he might be. Such is the case presented in FRANCONA: The Red Sox Years, written by Terry Francona and veteran Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy.

Timing is everything. Francona --- the son of Major Leaguer Tito Francona and himself a 10-year veteran --- came along when the Boston Red Sox were poised to break their 86-year World Championship drought in 2004 and thus became an instant folk hero. But as another saying goes, the hardest thing to do in sports is to repeat. Over his eight years at the helm, the Red Sox averaged 93 wins and were a perennial participant in the postseason (winning the World Series again in 2007), but it certainly wasn’t without the usual drama that befalls any sports enterprise such as injuries, inter-personal conflicts, and/or interference from upper management.

"The old sports saying goes that managers are hired to be fired. Regardless of one’s success, there will always be a time when a lack of production, a scandal, or just plain bad luck will lead to the dismissal of a team’s leader, regardless of what a good guy he might be. Such is the case presented in FRANCONA: The Red Sox Years..."

It’s this last aspect that frustrates Francona more than anything else. As a manager, you know as a matter of course that at some point you will have to juggle a lineup when a pitcher hurts his arm or a batter goes into a slump. What’s more difficult to deal with is the suggestions (always well-meaning) from those who are more concerned with the business aspects of the game. One of the team’s owners also helms NESN, the New England Sports Network, on which Red Sox games are broadcast. When ratings started to slip, one marketing wonk weighed in that the team had to win in a more exciting fashion. The 50-something Francona is young enough to be of the Moneyball generation, which employs statistics and situational projections, but he seems more aligned with the old-school, instinctual veterans. He makes his aggravation with those who would invade his purview quite evident.

Francona cuts quite a sympathetic figure. He come across as a decent sort: reliable, honest, loyal, a true father-figure who once told the parents of a pitcher who had been diagnosed with cancer, “We will take care of your son.” He spends more writing about these relationships than strategy and on-field action, which many readers might find more enjoyable than recent analytic offerings from fellow managers such as Tony LaRussa, his St. Louis Cardinals counterpart in that 2004 World Series (ONE LAST STRIKE: Fifty Years in Baseball, Ten and a Half Games Back, and One Final Championship Season) and perennial rival Joe Torre (THE YANKEE YEARS).

Francona’s ultimate downfall came when several members of the 2011 team seemed to just give up in what proved to be his final season with the Red Sox. Despite their 90-72 record, they finished in third place and out of postseason contention. Rumors of players drinking beer and chomping down chicken during games made Boston a laughingstock and embarrassed the owners, who laid the blame at the manager’s inability to maintain control. Francona, on the other hand, feels he was let down by a lot of people he had trusted, although he’s too much of a gentleman to point fingers.

“The impending disaster…did not happen in a vacuum,” the authors write. “There were signs all along the way. The Sox missed the veteran coaches who commanded their attention. They had a lot of aging players in the final year of their contracts. They had players placing personal rewards above team success.”

The eventual parting was acrimonious and left a bad taste on all fronts. Bobby Valentine was considered the right man to drop the hammer on the ball club, but under his stewardship, the Red Sox suffered their worst season over a 162-game schedule since 1960; by the end of the year, Valentine was gone. In the meantime, Francona was hired to lead the Cleveland Indians for 2013.

The construction of a memoir means that it’s the writer’s discretion as to what to include or leave out. Francona touches on his legitimate use of prescription medication to alleviate a number of physical ailments (enough so that it caught the attention of his family and employers), but barely mentions the separation from his wife of 30 years (“Few people knew that Francona was no longer living at home.”).

The major problem I have with the book is that it is written as a straight biography, that is, in the third person. Shaughnessy, an award-winning journalist with several books to his credit, could have easily done this on his own. Was it a marketing ploy, to use Francona’s name as lead writer, figuring it might garner more name recognition and increased sales than having Shaughnessy up front? It seems a tad disingenuous. Or is it just, to borrow a phrase used to describe a legendary Red Sox pain in the butt, Francona being Francona, a bit shy and uneasy to call attention to himself.

The situation reminds me of former Red Sox pitcher Tim Wakefield, who published KNUCKLER: My Life with Baseball’s Most Confounding Pitch with Tony Massarotti, also a Globe sportswriter. Like FRANCONA, Wakefield’s memoir is written in the third person.

Maybe it’s a Boston thing.

Reviewed by Ron Kaplan on February 8, 2013

Francona: The Red Sox Years

- Publication Date: April 1, 2014

- Genres: Nonfiction, Sports

- Paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Mariner Books

- ISBN-10: 0544227875

- ISBN-13: 9780544227873