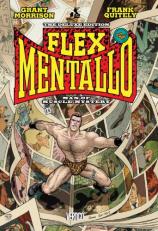

Flex Mentallo, Man of Muscle Mystery: The Deluxe Edition

Review

Flex Mentallo, Man of Muscle Mystery: The Deluxe Edition

Back in 2010, I had the privilege of interviewing Grant Morrison at length about his career and craft. Absent any public-relations motivation of a new and upcoming project, it was an opportunity to engage Morrison honestly about the process behind his many works and his approach to the medium. When I asked him about what he considered to be his best work, he told me, "Well, that is a hard one because I kind of like all of them, even the ugly, bizarre looking children. I love them all. It's hard between specific single issues and runs, but in terms of runs, it would probably be things like Flex Mentallo, which I feel refined a particular approach of mine and opened up some new ground other people hadn't quite explored, so I felt it was quite novel and quite effective at the time." First published in 1996, Flex Mentallo appeared after Morrison's acclaimed runs on Animal Man and Doom Patrol (where Mentallo made his debut), the monumental success of Arkham Asylum, and the shorter, often overlooked miniseries Sebastian O and Kid Eternity, as well as his original graphic novel Mystery Play. Interestingly, the first installment of Flex Mentallo was published as the first volume of Morrison's The Invisibles drew to a close. In many ways, Flex Mentallo is not only a bridge between the metafictional, ontological experiments of Animal Man and Doom Patrol and his later explorations of such themes in The Invisibles, All Star Superman, and others, but also a companion project to The Invisibles that completes an autobiographical narrative of Morrison's life.

Yet Morrison's own words that Flex Mentallo was "quite effective at the time" raises questions as to its longevity or, more specifically, whether Morrison's approach has held up over time. Audiences have seen Morrison explore the textual themes of reality and fiction colliding time and again. As with many of his books, Morrison asks his audience to be more than simply passive sponges. Instead, he often demands an active participation in the narrative itself. Unlike Doom Patrol, The Invisibles, or even Final Crisis with their multilayered, subtextual meanings as experiments in the form and composition behind visual storytelling, Flex Mentallo is the most fully realized and dutifully executed of these visions.

Morrison's personal adoration for the superhero genre and its central role in Flex Mentallo is apparent from the cover to issue one, an homage to the classic DC talking covers that called to readers from the spinner racks. Interestingly, these Silver Age classics were the forerunners to Morrison's own endeavors at comics, breaching the fourth wall and directly communicating with audiences. The parallels between Flex Mentallo and The Invisibles are fascinating from the very first page and beyond the simple explanation of cross-pollinating concepts bleeding from one series into the other. As bookended tomes in the autobiography of the author himself, it makes sense that both books were not only critical steps in Morrison's evolution as a writer, but also in coming to terms with aspects in his childhood and teenage years. Without getting too far afield and falling prey to the trappings of literary criticism and attempting to define what Morrison "means" with Flex Mentallo, it is vividly apparent that the book is Morrison's first full-fledged attempt to chafe at the bonds of reality-driven superheroes that plagued the "Dark Age" of modern comics since the late 1970s. In some ways, Flex Mentallo is Morrison's treatise against the Alan Moore and Frank Miller schools,and it is apropos that Morrison neglects the spandex and instead evokes the first great American superhero, the strongman, as his central figure.[1] In the decades before Siegel and Shuster's Superman, Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan, or even Philip Francis Nolan's Buck Rogers, there was Friedrich Wilhelm Mueller, better known to the world as Eugen Sandow, the very first bodybuilder. Sandow was not only the masculine ideal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and testament to gendered notions of body image, but also a showman who performed feats of power and strength on the stage. Much like Morrison driving against the tide of comics cynicism toward heroes, Mentallo is also a man out of time, as he recollects past, surreal adventures that call to mind the camp adventurism of 1950s and early 1960s comics. He asks, "What happened to the good old days? The heroes and villains, the team-ups and dream-ups. Seems to rain all the time these days. Never seems to get light…. Maybe it is the end of the world and there's nothing left to do but play with our old toys." Even as Mentallo tries to find comfort in channel surfing, he is hit with a barrage of negativity, including one channel focusing on a farmer building a rocket ship to send his infant son into space in the hopes of finding a better world. The question for Mentallo is repeated throughout the book: "Who's going to save the world now?"

Through the complimentary narratives of Mentallo's world intersecting with that of creator Wallace Sage's own, Morrison places himself in the Sage role, relying on the innocence of youth to bolster the sentimentality and adoration for Golden and Silver age comics. In fact, Morrison does a brilliant job of translating what it is actually like to experience a comic book within the pages of Flex Mentallo. Either in the child sequences where a young Sage reads and devours comics, the teen years when he actually creates and draws them himself, or the adult moments where an elder Sage discovers pages he drew as a child, Morrison illustrates that realism in comics is not exclusively cynical and bitter.

Apart from his debut with the "Blackheart" strip in three issues of Dark Horse Presents, Frank Quitely's work on Flex Mentallo was his break into ongoing work for the American industry. After working on small press and independent Scottish strips and marketing them at various conventions around the United Kingdom, Quitely transitioned into commercial comics work with Judge Dredd Magazine on "Missionary Man" and "Shimura," both of which he pencilled, inked, and colored. Interestingly, while the recoloring by Peter Doherty gives Quitely's pencils and inks a greater tonal variety, they do not alter the raw nature of his early, non-digital line art. In fact, while the recoloring of Flex Mentallo may go largely unnoticed by readers who either never experienced the four-issue run or audiences who overlooked how Tom McCraw's original gave the series a much different atmosphere and mood, the differences are somewhat astounding, even in the minutiae (such as Mentallo's haircolor). In some instances, the varied palette utilized by McCraw has been resoundingly dulled and sterilized of brighter hues in favor of much more muted grey tones. In others, however, where McCraw's colors were washed out or faded, Doherty has given them greater substance and altered their values, such as in the various superhero costumes of Limbo and his teammates. In turn, this recoloring is quite effective, as it increases the admiration and beauty of these Golden Age figures as entities of myth and objects of aspiration. Although facial features are much clearer and brilliant in the Doherty version, backgrounds and environments are potentially the most noticeable. It will be interesting to see if true Morrison fans find the hardcover recoloring an improvement or revisionist to the intended feel of the series.

In regards to draftsmanship and page composition, Quitely is far more conservative in Flex Mentallo than in later Morrison-penned series such as We3, New X-Men, All Star Superman, and Batman & Robin. Relying on a more traditional grid layout for his panel structure, Quitely rarely defies the five or six panels per page design. While the occasional splash-page profile shot, smaller inset panels utilized for quicker transitions between sequences (as shown on the right), or full page spread overlaid with smaller panels do appear, the majority rely on Quitely's technique of intensely focused, single-action per panel approach. That is not to say that Quitely does not include some innovative features. Apart from the cut-up nature of Mentallo employed on the cover and interior of chapter four, there is the single page in that chapter where Mentallo awakens after breaking through into the satellite headquarters. Even though Mentallo's position in the four widescreen panels does not shift, Quitely is able to use the absence of his mobility to force the audience to perceive everything else occurring on the page. Chapter four is by far the most experimental of the three; sequencing is at the core of Quitely's strengths, as he uses a stack of static Polaroids transitioning between the foreground and background as subtle motion cues to guide and direct the reader across the page. Flex Mentallo seems to be, in certain sequences and tone, an homage to Moebius' The Incal, particularly in the look of Mentallo's descent into the underground tunnels, as well as the scope and dimensionality in the interactions between Limbo and the young Wallace Sage as they traverse the creative process or in the Legion of Legions' crash into the earth.

Rounding out the deluxe edition is a selection of Quitely's sketches, thumbnails, and art boards. One of the most fascinating aspects is seeing his thumbnail process as he draws conceptual illustrations directly on Morrison's script pages. Yet, his breakdown of the cover design to issue #4 is by far the most striking as he arranged the individual panels and segments. Only the addition of actual Morrison script pages could have improved this special features section. An amazing work all around, Flex Mentallo is given a much deserved second life for both longterm fans and new readers in this latest treatment from DC Comics.

[1] Although it can be argued that the strongman was in fact the second great American superhero next to the penultimate Western hero, rarely did Western heroes complete such feats of strength, physical prowess, or routinely appear nude as Sandow did. Furthermore, apart from Davy Crockett's legendary bear killing at the tender age of three, most Western heroes' accomplishments were closely tied to the literary genre itself—hunting, Indian fighting, horsemanship, etc.

Reviewed by Nathan Wilson on April 6, 2012

Flex Mentallo, Man of Muscle Mystery: The Deluxe Edition

- Publication Date: April 10, 2012

- Hardcover: 128 pages

- Publisher: Vertigo

- ISBN-10: 1401232213

- ISBN-13: 9781401232214