Excerpt

Excerpt

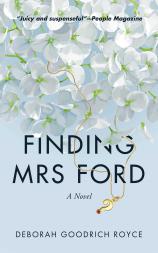

Finding Mrs. Ford

Thursday, August 7, 2014

Watch Hill, Rhode Island

A single gunshot cracks the air.

Seagulls flutter and levitate above the sand as Mrs. Ford’s dogs rise, barking. She, too, jumps just a little in her Adirondack chair and her feet lose their perch on the seawall. The echo reverberates across the sea and back to her at its edge. Mrs. Ford reaches down to pat the dogs.

Sound dissipates. Birds land. Dogs settle.

She doesn’t know why she startles every time this happens. She should know better. She does know better. This is the eight-a.m. shot signaling the raising of the flag at the Watch Hill Yacht Club, a short distance from her house. But even after all these years, she is rattled by the sound of gunfire.

Before her is the lighthouse at the tip of the peninsula. Its lawn slopes back from verdant green to jagged rocks as it rises to meet the mound that gives Watch Hill its name. From this lookout, Americans kept vigil for English vessels in the War of 1812. Lighthouse Point, nearly surrounded by water, is the place from which both Atlantic Ocean and Long Island Sound are visible. It is where they meet in a cocktail of currents that, with some frequency, foils even the strongest swimmer. It is the end of the peninsula, the end of the line. Next stop: water. From here, all lands are reachable. Aim the bow of your ship east, you’ll eventually hit Europe; aim it southeast, Africa. Keep going, and you’ll circumnavigate the globe.

It is an early summer morning. Watch Hill is a summer town. Built by the summer people for the summer people. They came from Cincinnati, St. Louis, Detroit, these people, titans of industry from the Midwest, to Rhode Island to build their retreats, fifteen-bedroom “cottages” on this narrow spit of land. Not to Newport, Watch Hill’s famous cousin to the east. Some say it was because many of them were Catholic and Newport would not welcome them. Whatever their reasons, they came. They came in the Victorian age, the Edwardian age, the turn of the last century. Mrs. Ford is an example of those who come to Watch Hill still.

She smiles to herself when she thinks of the lapel buttons that circulate in Watch Hill among the cognoscenti. Every summer they reappear, although she does not know who makes them. I Am Watch Hill one of them states. I Married Watch Hill announces another. In recent years, the Millennials have added a new twist—I Partied Watch Hill. Everyone knows who is who. The buttons aren’t really necessary, but they serve to amuse. Mrs. Ford knows where she fits in in this button order.

The sun bounces back from the straight line of gold it casts across the bay from its low angle to her left, catching a few pale strands of hair that have escaped from her ponytail, and deepening the lines around her eyes. Mrs. Ford, whose age is somewhere in the middle years, is dressed in white jeans and dark glasses, a striped fisherman’s shirt, and Keds—tribal costume of the natives.

She inhales deeply, willing the return of her equilibrium. She smells the beach roses that separate her lawn from her neighbor’s, the salt of the sea, the coffee in the mug that rests on the arm of her chair. She sees her dogs sitting at her feet, patiently waiting for her to finish this morning ritual of quiet contemplation before they begin the routine much dearer to their hearts: the morning walk. With one hand, she reaches down to touch them, one sweet little doggy body after the other. She lingers there for the comfort the feel of them gives her.

Showtime.

She grabs the double lead and attaches it to her Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, but not before kneeling down to bury her face in their red and white spotted fur. They will always smell like puppies to her—sweet, salty, milky—no matter how old they get. She submits to their kisses, laughs, and gets up. She leaves her coffee and heads toward the porte-cochère of the gatehouse that marks the edge of her property. The proscenium arch of this entrance creates an irresistible invitation for passersby all summer long. The tourists can’t help themselves. Looking through the porte-cochère at the roses, the lighthouse and the sea, centered so perfectly, people wander through it, like entering the frame of a painting, to take a photograph. These trespassers alarmed her when she first came here, when she married Jack and began to spend her summers in Watch Hill. She still doesn’t like finding strangers on her land, but she has come to accept the fact of them.

This morning, it is still too early for tourists. She steps out of her driveway and, as is her custom, is about to turn to the right. She almost does not see the car, non-descript, late-model American, parked to the left of her house. She starts off, the dogs are pulling her, but something makes her freeze. Some old fighter’s instinct, nearly buried by years of comfort, but not quite dead.

She stops. She turns back. She considers the car.

A Crown Victoria?

The sun glints off of its windshield—mirroring back an image of the scene she already knows—the green of the trees, the blue of the sky, the silent glide of a lone, whitegull. A place for everything and everything in its place.

Once again on this perfect summer day, she has conjured past ghosts come to haunt her. Deliberately, she shakes off her nerves and slackens her grip on the dogs that she has been holding back. She turns to begin her walk.

The car shifts into gear and rolls after her.