Excerpt

Excerpt

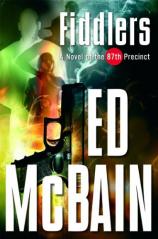

Fiddlers: A Novel of the 87th Precinct

The

manager of Ninotchka was a wiseguy named Dominick La Paglia. Not a

made man, but mob-connected, with a string of arrests dating back

to when he was seventeen. Served time on two separate occasions,

once for assault with intent, the other for dealing drugs. He

insisted the club was clean, you couldn't even buy an inhaler in

the place.

"We get an older crowd here," La Paglia said. "Ninotchka is all

about candlelight and soft music. A balalaika band, three

violinists wandering from table to table during intermission, the

old folks holding hands when they're not on the floor dancing.

Never any trouble here, go ask your buddies up Narcotics."

"Tell us about Max Sobolov," Carella said.

This was now eleven P.M. on Wednesday night, the sixteenth day of

June. The three men were standing in the alleyway where the

violinist had been shot twice in the face.

"What do you want to know?" La Paglia asked.

"How long was he working here?"

"Long time. Two years?"

"You hired a blind violinist, right?"

"Why not?"

"To wander from table to table, right?"

"Place is dark, anyway, what difference would it make to a blind

man?" La Paglia said. "He played violin good. Got blinded in the

Vietnam War, you know. Man's a war hero, somebody aces him in an

alleyway."

"How about the other musicians working here? Any friction between

Sobolov and them?" Meyer asked.

"No, he was blind," La Paglia said. "Everybody's very nice to blind

people."

Except when they shoot them twice in the face, Carella

thought.

"Or anybody else in the club? Any of the bartenders, waitresses,

whoever?"

"Cloakroom girl?"

"Bouncer? Whoever?"

"No, he got along with everybody."

"So tell us what happened here tonight," Carella said.

"Were you here when he got shot?"

"I was here."

"Give us the sequence," Meyer said, and took out his

notebook.

The way La Paglia tells it, the club closes at two in the morning

every night of the week. The band plays its last set at one thirty,

the violinists take their final stroll, angling for tips, at a

quarter to. Bartenders have already served their last-call drinks,

waitresses are already handing out the checks . . .

"You know the Cole Porter line?" La Paglia asked. "'Before the

fiddlers have fled'? One of the greatest lyrics ever written.

That's what closing time is like. But this must've been around ten,

ten thirty when Max went out for a smoke. We don't allow smoking in

the club, half the geezers have emphysema, anyway. I was at the

bar, talking to an old couple who are regulars, they never take a

table, they always sit at the bar. It was a slow night, Wednesdays

are always slow, they were talking about moving down to Florida.

They were telling me all about Sarasota when I heard the

shots."

"You recognized them as shots?"

La Paglia raised his eyebrows.

Come on, his look said. You think I don't know shots when I hear

them?

"No," he said sarcastically. "I thought they were backfires,

right?"

"What'd you do?"

"I ran out in the alley. He was already dead. Laying on his back,

blood all over his face. White cane on the ground near his right

hand."

"See anybody?"

"Sure, the killer hung around to be identified."

Meyer was thinking sarcasm didn't play too well on a mobster.

The Sobolov family was sitting shiva.

Meyer had been here, done this, but today was the first time

Carella had ever been to a Jewish wake. He simply followed suit.

When he saw Meyer taking off his shoes outside the open door to the

apartment, he took off his shoes as well.

"The doors are left open so visitors can come in without

distracting the mourners," Meyer told him. "No knocking or ringing

of bells."

He was washing his hands in a small basin of water resting on a

chair to the right of the door. Carella followed suit.

"I'm not a religious person," Meyer said. "I don't know why we wash

our hands before going in."

This was all so very new to Carella. There were perhaps two dozen

people in the Sobolov living room. Five of them were sitting on low

benches. Meyer later explained that these were supplied by the

funeral home. All of the mirrors in the house were covered with

cloth, and a large candle was burning in one corner of the

room.

In accordance with Jewish custom, Sobolov had been buried at once,

and the family had begun sitting shiva as soon as they got home

from the funeral. This was now Friday morning, the eighteenth day

of June. The men in the family had not shaved. The women wore no

makeup. There was a deep sense of loss in this house. Carella had

been to Irish wakes, where the women keened, but where there was

also laughter and much drinking. He had been to Italian wakes,

where the women shrieked and tore at their clothing. The prevailing

mood here was silent grief.

The apartment belonged to Max's younger brother and his wife. The

brother's name was Sidney. The wife was Susan. Both of Max's

parents were dead, but there was an elderly uncle present, and also

several cousins.

The uncle spoke with a heavy accent, Russian or Middle European, it

was difficult to tell which. He told the detectives stories about

when Max was still a little boy. How his parents had purchased for

him a toy violin that Max took to at once . . .

"You should have seen him, a regular Yehudi Menuhin!"

The brother Sidney told them that his parents had immediately

started Max taking lessons . . .

"On a real violin, never mind a toy," the uncle said.

. . . and within months he was playing complicated violin pieces .

. .

"His teacher was astonished!"

"He had such an aptitude," one of the cousins said.

"A natural," Sidney agreed. "He was so sensitive, so

feeling."

"The kindest person."

"Such a sweet little boy."

"When he played, your heart could melt."

"All his goodness came out in his playing."

"What a player!" the uncle said.

Sidney told them that no one was surprised when his brother was

accepted at the Kleber School, or when Kusmin put him in his

private class. "Alexei Kusmin," he explained. "The head of violin

studies there."

"Max had a wonderful career ahead of him."

"But then, of course . . ." one of the cousins said.

"He got drafted."

"The war," his uncle said, and clucked his tongue.

"Vietnam."

"Twenty-fifth Infantry Division."

"Second Brigade."

"D Company."

"B Company, it was."

"No, Sidney, it was D."

"I used to write to him, it was B."

"All right, already. Whatever it was, he came back blind."

"Dreadful," Susan said, and shook her head.

"It began at the hospital," his uncle said. "The drug use."

"Before then," his brother said. "It started over there. In

Vietnam."

"But mostly, it was the hospital."

"Medicinal," his brother said, nodding.

"The VA hospital."

This was the first the detectives were hearing about drug

use.

They listened.

"And also, you know, musicians," one of the cousins said. "It's

prevalent."

"But mostly the pain," the uncle said.

"Understandable," another cousin said.

"Besides, everybody smokes a little grass every now and then," a

third cousin said.

"It should only be just a little grass," the uncle said, and wagged

his head sympathetically.

"And yet," his brother said, "right to the day he died, he was the

sweetest, most loving person on earth."

"A wonderful human being."

"A mensch," the uncle agreed.

Only one of the girls was really beautiful, but the other one was

cute, too. He hadn't expected either of them to be prizes. You call

an escort service, they're not about to send you a couple of movie

stars.

The woman on the phone yesterday had said, "You know what this is

gonna cost you, man?"

She sounded black.

"Price is no object," he'd said.

"Just so you know, it's a thousand for each girl for the night.

Comes to two K, plus a tip is customary."

"No problem," he'd said.

"Usually twenty percent."

He thought this was high, but he said nothing.

"Which'll come to twenty-four hundred total. You could make it an

even twenty-five, you were feeling generous."

"Credit card okay?" he'd asked.

"American Express, Visa, or MasterCard," she'd said. "What time did

you want them?"

"Seven sharp," he'd said. "Can you make it a blonde and a

redhead?"

"How about a nice Chinese girl?"

"No, not tonight."

"Or a luscious sistuh?"

He wondered if she had herself in mind.

"Just a blonde and a redhead. In their twenties, please."

"Le'me find you suppin nice," she'd said.

The blonde was the real beauty. She told him her name was Trish. He

didn't think this was her real name. The redhead was the cute one.

She said her name was Reggie, short for Regina, which he had to

believe because who on earth would chose Regina as a phony name? He

guessed Trish was in her mid-twenties. Reggie said she was

nineteen. He believed that, too.

"So what are we planning to do here tonight?" Trish asked.

She was the bubbly one. Wearing a short little black cocktail

dress, high-heeled black sandals. Reggie was wearing green, to

match her green eyes. Serious look on her Irish phizz, she should

have been wearing glasses. Better legs than Trish, cute little

cupcake breasts as opposed to the melons Trish was bouncing around.

Neither of them was wearing a bra. They both wandered the hotel

suite like it was the Taj Mahal.

"Lookee here, two bedrooms!" Trish said. "We can try both of

them!"

Before morning, they'd used both beds, and the big Jacuzzi tub in

the marbled bathroom. It hadn't worked anywhere.

"Why don't we try it again tonight?" Trish suggested now.

"I have other plans," he told her.

"Then how about tomorrow night?" she said.

"Maybe," he said.

"Well, think about it," she said, and gave his limp cock a playful

little tug, and then went off to shower. Reggie was drinking coffee

at the dining room table, wearing just her panties, tufts of wild

red hair curling around the leg holes. Freckles on her bare little

breasts. Nipples puckered.

"We could do this alone sometime, you know," she said.

He looked at her.

"Just you and me. Sometimes it works better alone."

He kept looking at her.

"Sometimes two girls are intimidating. Alone, we could do things we

didn't try last night."

"Like what?"

"Oh, I don't know. We'll experiment."

"We will, huh?"

"If you want to," she said. "Give it another try, you know?" She

lifted her coffee cup, drank, put it down on the table again. "And

you wouldn't have to go through the service," she said.

Down the hall, he could hear the shower going.

Excerpted from FIDDLERS: A Novel of the 87th Precinct ©

Copyright 2005 by Hui Corp. Reprinted with permission by Harcourt.

All rights reserved.