Excerpt

Excerpt

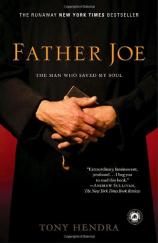

Father Joe: The Man Who Saved My Soul

Chapter One

How I met Father Joe:

I was fourteen and having an affair with a married woman.

At least she called it an affair; she also said we were lovers, and

on several occasions, doomed lovers. An average teen, I was quite

content with these exalted terms; in practice, however, I only got

to second base with her. (I didn't yet know it was second base, as

I was growing up in England.)

It was only rather later too, when I saw The Graduate, that I

realized my Mrs. Robinson may have been somewhat older than she

admitted to --- which was twenty-two. To my unpracticed eye she

could certainly pass for that; I was still young enough that any

woman with breasts and a waist and her own teeth was roughly the

same age as any other --- which is to say a grown-up --- and the

mysterious repository of unimaginable pleasures deserving . .

.

. . . hideous, very specific torments. The fly in the ointment of

this relationship was that we were both Catholics. At least in

theory (theory to me, practice to her), there was a terrible bill

being racked up somewhere, calibrating the relative sinfulness of

everything we did, every gesture made, every word exchanged, let

alone every kiss. Should death strike, should lightning fork from

one of the huge trees outside into our concupiscent bodies, should

one of the experimental jets being developed over the hill at

DeHavilland's disintegrate and plummet to earth (as they often

threatened to do when trying to break the sound barrier), turning

her trailer into a fireball, down, down we would plunge, into the

bowels of Hell, unshriven, unforgiven, damned for all eternity to

indescribable suffering.

A lot of what little conversation we had --- much more the norm

were interminable, agonized, what she called "existential" silences

--- concerned whether we should even be having a conversation,

should even be together for that matter, doomed lovers in the

throes of a hopeless and illicit liaison, wrestling with the

irresistible temptation of being in the same neighborhood, town,

county, country, planet, dimension. We were so bad for one another,

she said, such a monumental occasion of sin for each other, it was

playing with fire; oh, if only we'd never met and plunged ourselves

into this cauldron of raging emotions from which there was no

escape!

These sentiments were very new to me. My instinctive response was

that they were pretty goofy, but what did I know? I dimly

recognized that I was going through some kind of passage out of

childhood and would from now on be required to learn, without being

taught, how grown-ups acted and spoke. Best not to rock the boat,

by suppressing a classroom splutter. I had a good thing going. Mrs.

Bootle was no slouch in the looks department. Perhaps this was the

way women always spoke in extremis. Books were my only guide and so

far it all seemed pretty true to form --- like being in The Thorn

Birds if it had been written by Christina Rossetti.

But it had been a long time since the first hesitant kiss, and we'd

done lots of kissing since. I was getting restless, anxious to find

out what would be the next cauldron of raging emotions from which

there was no escape.

Now on a bleak Saturday morning in the damp, dank early spring of

green, green Hertfordshire, England, The World, The Solar System,

The Universe, in the year of our Lord 1956, I was about to find

out.

She stood at the kitchen end of the trailer, where the sink was,

surrounded by dirty dishes, her back to the picture window through

which a waterlogged plot ran down to the river, swollen and sullen

in the rain, the depressed little green caps of her

higgledy-piggledy vegetable garden poking through the mud. "Should

we?" she said in an agonized half-sob. "I think we should," I

replied, having no idea what she was talking about. "But . . . but"

(she never used just one "but" --- always at least two) "it will be

the end, the point of no return, all will be lost." "Well, then,"

said the voice of proto-adult reason, "perhaps we shouldn't." "No!

no! yes! yes!, how can we help ourselves, I'm swept away, I tell

you, let's cast all caution to the winds! Turn round."

I did as I was bid, averting my head and closing my eyes, mad

excitement welling up through my body from my heels to my eyelids.

This must be it, whatever it was. From behind me came surreptitious

noises: rustling clothes, eyelets popping, zippers unzipping, hot

little pants of effort.

"Turn round," she whispered hoarsely. I did. "Open your eyes." I

did. Her eyes were now closed, her head inclined to one side, long

hair draped over her white, slight, naked shoulders, framed by the

rain-drenched window, the Madonna of the drizzle. My eyes ratcheted

nervously down to her breasts. They were quite small, of slightly

different sizes, and rather flat. Well, actually very flat. Making

the nipples seem somewhat larger than I would have expected. The

baby --- to all appearances a sweet little scrap --- must have been

a voracious feeder.

These were my first live breasts. The only ones I'd seen to date

had been in nudist magazines. Were they all like this? I'd just

read The Four Quartets for the first time: the image of Tiresias

popped into my head and wouldn't budge.

Then she kissed me. Her lips and face were hotter than usual, like

my little brother's when he had a temperature. She came closer. I

could feel the warmth of her skin through my shirt and then what

must have been those nipples. I put my hand inside her rolled-down

dress between her hip and her belly. "No! no!" she whispered,

covering my hand with hers. But she pushed it down infinitesimally.

As I followed her pressure, she resisted, pulling it up even more

infinitesimally. "You mustn't!" she sobbed. "Think of the sin, the

mortal sin, the eternal flames!" Then the downward pressure again.

A textbook case of no-but-yes --- though I was too young to grasp

such psycho-sexual antics. I followed her hand down for a few

millimeters. It resisted. Up we went. But not so far --- we were

definitely making headway. Down . . . up, down, up, down . . . My

whole hand was inside her dress now, inching inexorably earthward.

Her skin was silky and her flesh deliciously soft. And it kept

getting softer. Where were we? Way down there, surely? Waves of ---

some unknown emotion --- shuddered through me. I was dizzy with

excitement, Tiresias having definitely taken a powder . . .

Ben and Lily Bootle had first appeared at the local Catholic church

a year earlier. She was petite and slender, he was big and rangy, a

head or more taller than his mate. Though she was very pregnant she

wore a clingy, full-length shift-like dress, emphasizing her milky

breasts and bulging belly. Open leather sandals advertised tiny,

shapely feet. Her outfit had a distinct bohemian flair in a Sunday

congregation made up for the most part of dowdy English widows and

hungover Irish laborers with the occasional large unruly family and

cigarette-ashen wife.

Ben looked as though he'd just emerged from a night of

electroshock. His thick wiry hair stood up in uncombed clumps and

spikes, his clothes were always rumpled with at least one element

undone, and he wore battered tortoiseshell-rimmed glasses of

impressive thickness.

They seemed to have no friends and kept very much to themselves; no

one even knew where they lived, least of all our ancient and

embottled parish priest, Father B. Leary (the "B." --- for

Bartholomew --- leading us altar boys to call him Father

Bleary).

In due course a baby Bootle appeared, which Lily carried in a

rather self-consciously peasanty manner on her hip. Its gender was

unclear, since it wore no conventional baby garments, being wrapped

regardless of season in what my mother acidly called "swaddling

clothes." But still no one had found out a whole lot about them,

except that Ben was some kind of scientist doing hush-hush work on

jets or rockets or something. Since the church was the only place

they made contact with us earthlings, it had also been noted that

Ben was quite devout. As well as Sunday Mass he would appear at

non-obligatory services like Rosary evenings to pray for the

Godless Soviets.

Though our paths hadn't crossed, serving Mass was also one of my

chores, which I loathed not only because of the tongue-twisting

Latin responses but also because Father Bleary had last brushed his

teeth to celebrate victory over the Kaiser and his breath would

have stopped even the leper-hugging St. Francis dead in his tracks.

One moment of the Mass in particular, the Lavabo, at which the

server is required to ritually wash the priest's fingers, putting

the anointed face inches from yours, was like being gassed in the

trenches at Verdun.

My level of devotion was at a fairly obligatory level. I was the

product of what the Church called a "mixed marriage" --- one

between a Catholic and a non-Catholic, which in my father's case

meant nothing fun like a Muslim or a Satanist, but simply a

desultory agnostic, a "nonbeliever in anything much, really."

Ironically, he was a stained-glass artist, so he spent far more

time inside churches and knew far more about Catholic iconography

than his nominally Catholic brood.

My mother was what the priests called a "good" Catholic. She

attended Mass every Sunday and holiday of obligation, went to

confession once a month, shelled out handfuls of silver when

required, but otherwise, as far as I could tell, didn't allow the

precepts of the Gospels and their chief spokesman to interfere much

with her daily round of gossip, bitching, kid-slapping,

neighbor-bashing, petty vengeance, and other middle-class

peccadilloes.

One aspect of my mother's behavior did seem to me to be well up the

scale of venial sin, if not all the way to mortal: she shared with

local non-Catholics a broad prejudice against the Irish laborers

who were appearing in our village in considerable numbers, as they

were in many other parts of England, to work in the ongoing

reconstruction of postwar Britain, particularly the new motorways.

All of whom were Catholic.

The vast majority of these workers were fleeing chronic

unemployment in the new Republic and brought with them habits of

poverty that didn't sit well with the upwardly mobile Protestant

burghers of southeast England: the drinking and plangent midnight

singing in the street --- naturally --- but also the taking a leak

round any old corner, the possession of only one jacket and pair of

trousers --- worn to the construction site every morning, to the

pub every night, to church on Sunday, and to sleep in

anytime.

Mostly they were loathed just for being Irish. The depth of British

odium for a people they robbed, murdered, enslaved, and starved for

eight hundred years is hard to exaggerate; I often experienced it

at second hand when gangs of local toughs would run me to cover as

I walked home from school, screaming "dirty Catholic go home" and

heaving stones at me. True, British anti-Catholic prejudice harked

back to the seventeenth century and was institutionalized in many

ways, but it's unlikely these troglodytes had the excesses of James

II on their tiny minds; for them, "Catholic" and "Irish" were

interchangeable slurs.

I hadn't made this connection yet; kids tend to take prejudice in

their stride, a fixed peril you find a route around on your journey

toward adulthood. For the moment its larger meaning was opaque and

my dealings with it open to compromise if not outright

collaboration.

Example: every November fifth in England, Guy Fawkes --- a Catholic

conspirator of the early seventeenth century who almost succeeded

in blowing up the Houses of Parliament --- is burned in effigy on

thousands of bonfires across the land. While it's fine that Guy

Fawkes be remembered for what he was --- an odious antidemocratic

terrorist --- this custom has for centuries also expressed and

refueled anti-Catholic prejudice. So every Sunday before Guy Fawkes

Day, Catholic priests would condemn it and order Catholics not to

participate. For me --- a serial pyromaniac --- the prospect of no

bonfire was bad enough, but it also meant missing the truly

glorious part of Guy Fawkes Day: fireworks.

In a mixed marriage this sort of thing could be sheer poison. The

arrangement my father worked out was as follows: (a) fireworks,

naturally --- kids have to have fireworks; (b) smallish bonfire

(though I'd always creep out in the night and pile it higher, and

if possible stick tires in it); (c) absolutely no guy (as the

effigy of Mr. Fawkes is known). When my mother objected that we

were still symbolically burning a Catholic, Dad would reply yes,

but every time we let off a firework we were symbolically blowing

up the Houses of Parliament.

So then we'd celebrate the same prejudice that got rocks thrown at

my head on the way home from school. And the same prejudice that

had the good villagers muttering about lazy drunks and refusing to

rent rooms to the Irish or serve them in their shops. I found this

obnoxious in them and, to the degree that she agreed, in my mother.

I'd like to pretend that I was smart enough at fourteen to have

worked all this out in total consistency, but in fact I had simply

picked up from somewhere an aversion to discriminating against

people because they had next to nothing and did work no one else

wanted to do.

Unbeknownst to me there was more at work than mere altruism; a

deeper bond made me take the Irish side.

If challenged, Mum would have said she was just being protective in

putting as much distance as possible between us kids and the boyos

down the pub. (She certainly did in church, where she would sit as

far away as she could from her boozy coreligionists, moving up a

row or two if they got too close.) Something much juicier, however,

was going on beneath these maternal protestations.

She always insisted that her maiden name --- McGovern --- was

Scottish, even though it began with "Mc" as all the finest Irish

names do, not "Mac" like all the finest Scottish ones. She and the

other four McGovern sisters had indeed been born in Glasgow, so she

did have that on her side. But as one of her older sisters would

say, less skit- tish than she about their true origins: if a cat

has kittens in the oven, are they biscuits? Nonetheless Mum stuck

to her guns; we were Scottish and proud of it, och awa' the noo. Of

course the British weren't much fonder of the Scots than they were

of the Irish, but on the spectrum of Anglo-Saxon anti-Celtic

prejudice she evidently felt it was better to be ridiculed as

Scottish than despised as Irish.

Once when I was about ten, Dad brought home a book of Scottish

tartans --- he was painstaking about the heraldic and chivalric

symbols he used in his windows --- and I got very excited over the

rich old aristocratic patterns. Surely with our deep Scottish roots

we must have a tartan? That in turn would mean we could wear a

kilt, och awa' the noo. This line of questioning threw Mum for the

biggest loop so far. "Um --- that one," she said, pointing at the

Campbell tartan. "But that's the Campbell tartan," I objected.

"Well," she fired back, "the McGoverns are part of the Campbell

clan."

Only later, when I moved to New York, where I met dozens of

McGoverns, every one as Irish as a pint of stout, did all become

clear; I realized that the closest my maternal ancestors had ever

come to the Highlands and a Campbell kilt was the wilds of County

Leitrim.

If I'd known at the time how Irish I was, I mightn't have been so

pleased about it. I wasn't a whole lot keener about being a

Catholic. This had less to do with being on the receiving end of

prejudice than with the growing gap between what I heard in church

and learned in school. Not that my mother hadn't tried to prevent

the gap from growing. The mixed-marriage contract the Church

required the infidel half of the couple to sign said that all

resulting offspring had to be brought up in the Faith. If humanly

possible, this meant being sent to a Catholic school.

Between the ages of five and eight, therefore, I had gone to the

nuns, in this case Dominicans, followers of the intrepid Spanish

preacher Domingo de Guzman, aka St. Dominic, scourge of the Cathars

and inventor of the very first version of the Inquisition. The good

sisters were known by baffling names like Sister Mary Joseph,

Sister Mary Frederick, and Sister Mary Martin. While they never

actually condemned us first-graders to an auto-da-fé, they

certainly devised some Inquisition-level torments to instill the

One True Faith in us; and, to be fair, they were effective. (Why

did God make you? God made me to know him love him and serve him in

this world and to be happy with him forever in the next.) There are

several concepts and assumptions in this catechesis which might be

a little beyond a six-year-old, but half a century later I can

still recite it in my sleep.

The next stop after the good sisters was the good brothers.

These hard men ran a joint called, benignly enough, St. Columba's,

quartered in a sprawling old Victorian mansion. I've blanked on the

name of their order; I'd like to think it included some phrase like

St. Aloysius The Impaler, but it was probably more along the lines

of the Holy Brothers of the Little Flower. They were, to a man,

Irish; in all my years in and out of the Church I've never come

across a gang so utterly unholy. They dressed in lay clothes and

wore lay haircuts, and as far as anyone could tell, they performed

no religious observances whatsoever. Nothing distinguished them

from what they appeared to be --- members of a sleeper cell of the

IRA or participants in some particularly vicious form of organized

crime.

They beat us with their belts, they beat us with their metal rulers

--- the thin side, not the flat. They set dogs on boys who strayed

into their quarters, they had beer on their breath at morning

assembly. They encouraged the older boys --- especially if they had

Irish names --- to beat the crap out of the smaller ones ad majoram

Dei gloriam. This toughening-up process would turn us seven- and

eight-year-old boys into good soldiers of Christ. Religion was

invoked only as a prelude to violence; the fires of Hell awaited

any infraction or indiscipline, especially the mortal sin of being

anywhere near a Holy Brother with a morning head. Threatening the

fear of damnation had limited force --- as far as I could tell, I

was already in Hell.

Disputes between boys were settled on the spot by boxing bouts ---

not with padded sparring gloves either, but ten-ounce ring gloves.

The first time this happened to me, I tearfully objected that I

didn't know how to box and couldn't I run a race or something,

whereupon Brother Colm, who happened to be headmaster, snarled,

"You'll settle it with the gloves --- as Christ intended." I

scrolled mentally through the Gospels for occasions where Jesus had

gone a couple of rounds with the Pharisees or Sadducees. Nothing.

Then the other boy hit me in the face and knocked me out.

After I came home for the umpteenth time with a bloody nose or my

arse covered in welts or a smashed hand bandaged in a handkerchief

--- there being no school nurse at St. Columba's, the soldiers of

Christ performed their own first aid --- my parents decided that

the mixed-marriage contract notwithstanding, my Catholic education

was at an end.

My first Protestant stop was a small Church of England prep school

with pretensions to be rather classier than was merited by its

location --- a nouveau-riche dormitory town north of London. I

didn't like it much, and perhaps as payback to some greater

educational authority in the sky, I became possessed by a demon of

petty crime, a juvenile delinquent playing right into the

stereotype of the perfidious Irish Catholic.

Excluded from morning prayers each day and C of E religious

instruction several times a week, I spent the time allocated for

spiritual reflection rifling through the pockets of my classmates'

coats and jackets in the cloakroom. I could garner vast sums this

way --- sometimes as much ten or fifteen shillings a day, a huge

sum for a preteen in the mid-fifties. The proceeds were then spent

at the local Gaumont cinema.

My visits were so regular that Mum became convinced that it really

did take three and a half hours to get home on the bus, not the

official hour or so. I caught --- at least four or five times each

--- the Ealing comedies, Olivier's Henry V, Billy Wilder's Sunset

Boulevard, and a long succession of early Technicolor Hollywood

goodies, best of all the garish biblical epics that aging 1930s

moguls were pumping out to nip TV in the bud (and in some cases to

subliminally bolster the scriptural claims of the new state of

Israel). My all-time favorite was Samson and Delilah, with

ravishing Yvonne de Carlo as the hair- clipping houri and bulging

Victor Mature as Samson. It riveted me that Samson's breasts were

almost as big as Delilah's. One of my earliest sexual crises had

been rage and bafflement that I would never be able to have a baby,

and I found Mr. Mature's bosoms strangely comforting.

I became adept at theft, staggering my raids and leaving the

heavier copper and bronze coins in the victims' pockets so they

wouldn't discover their loss till they were out of school, where it

could be blamed on their own carelessness. I'm sure the authorities

were leaning over backward to be Christlike and tolerant, hesitant

to conclude that the school's only Catholic was ripping off his

Protestant classmates.

Eventually the well-meaning dolts put a patrol on the cloakroom,

but by then the demon had parted as abruptly as it came, leaving me

with no further taste for felony. I'd scored high in the

eleven-plus exams and won a place at the best school in the county;

then, to everyone's surprise, including my own, I won several

events at the end-of-term athletics meet and was declared my year's

champion. A top student and a track star could hardly be a thief.

So the good Prots not only provided me with a small fortune in

stolen goods and a solid grounding in Hollywood movies, they sent

me on my way with a silver cup.

Robbery, violence, Hollywood --- all classic enemies of Catholic

piety. By the time I arrived at St. Albans School at the age of

eleven, I was already drifting away from Holy Mother Church. St.

Albans was nominally C of E; it was also the oldest surviving

school in England, having been founded by the Benedictine monks of

St. Albans Abbey in a.d. 948. This meant, for what it was worth,

that it had been Catholic far longer than it had been Church of

England, from 948 to the Dissolution being roughly six hundred

years while the Protestants had had it only since then, a paltry

four hundred. Up until the Second World War it had been a minor

public school, but by the time I got there, the socialist leveling

that was transforming British education had swept most of this

religious and classist history away. St. Albans was a

government-funded feeder school for the coming meritocracy, and

academic excellence was its overwhelming concern.

The level was scary. Where up to this point I'd had little trouble

making it to the top rank of any class, here I was just one of the

anonymous striving middle. The aim became simply to keep your head

down and your marks up. The syllabus included Latin and Greek, but

there was no doubt about the long-term utilitarian emphasis ---

math and science, with English (and French) literature a distant

third.

Our classes were seated in alphabetical order, and right in front

of me for my first three years was an inarticulate homunculus named

Stephen Hawking. The great utility of Hawking to his classmates was

that he could do math and physics homework at the speed of light

--- a concept, by the way, only he seemed able to grasp. He usually

had the homework finished by the end of lunch hour, and the

thuggier element in his class --- including me --- found it easy to

persuade him to share it. Our math and physics marks were terrific,

until the inevitable day of a test, which Hawking would finish in

minutes and sit snuffling and grinning and doodling for the

remainder of the hour, while the rest of us sweated through the

now-incomprehensible scientific runes.

The custom of using Hawking as a source for spiffy homework marks

persisted until sometime in the third year when he began moving at

warp speed. Now he would take a fairly simple problem of, say,

calculus as the pretext for a far-ranging dissertation expressing

itself in pages and pages of equations and formulae that no doubt

stopped just short of the event horizon. The cloddier types duly

copied all this out, figuring it would lead to massive bonus marks.

It didn't, and soon Hawking disappeared from all math classes to

pursue his destiny alone.

The fine print in the Church's mixed-marriage contract demanded

that where offspring were forced to attend a non-Catholic school,

religious instruction should counteract the heathen lies with which

their little ears were filled. In practice my syllabus was so

arduous that I had no time for religious instruction even if it had

been available in a small country village. So there was no

counterweight to my favored subjects, history and organic

chemistry, leading my education in an increasingly secular

direction.

History textbooks hadn't caught up with postwar historical thought

or research; they tended to be Anglocentric, casually

anti-Catholic, and often virulently antipapal. This was very much

the case in my favorite period --- the Middle Ages. One of the more

egregious examples of skewed papal history concerned a local lad,

Nicholas Breakspear, who in the mid–twelfth century rose from

being Abbot of St. Albans to become Adrian IV, the only Englishman

ever to attain the papacy. Breakspear, it was emphasized, was that

very rare bird: a good Pope.

A teenager eagerly and uncritically lapping up all such great

stuff, I had no frame of reference to judge it by. As the Curial

bureaucrats who wrote the mixed-marriage contract no doubt foresaw,

I much preferred the new analysis to the old, maternal, pro-Church

one.

My fascination with chemistry added fuel to the heretical pyre. The

clear message of chemistry --- especially of lab experiments, which

I'd never done before --- was that everything in the

phenomenological world had an explanation, and that if it couldn't

yet be explained, further research would soon do the job. It didn't

take a genius to figure out that the standard proof of God's

existence ("someone must have made it all") began to get a little

rocky in the lab. There was the evidence in the microscope slide:

amoebas reproduced all by themselves without a flash of lightning

or a big finger pointing at them, just as they had long ago in

kicking off the chain of evolution that led to Hawking.

For me there was another factor too, in some ways more

all-encompassing and from a strict doctrinal point of view more

insidious. I had fallen in love with the Hertfordshire

countryside.

Hertfordshire contains many of the signature images of the great

landscape artist John Constable: slow, meandering streams winding

through lush meadows intersected with vast stands of elm; gentle

hills and soft bosomy fields trimmed with neatly laid hedges of

hawthorn and hazel; animals of all kinds, wild and domestic, in

huge profusion; rich clay and loam, its vegetation moist and

bulbous, bursting with primal juice. You could hardly break a stalk

in the meadows without some thick or milky essence bleeding from

the plant.

I don't mean I passed my youth in a Wordsworthian trance. I had

goals. The most important was the killing of small waterfowl and

the roasting of them over an open fire. Hunting in turn required

the construction of weapons --- first spears with, for one brief

and frustrating period, hand-chipped flint tips, but later and more

practically, bows and arrows.

In the wonder years that I spent wandering the countryside with my

lethal weapons, I never managed to kill a single living thing, let

alone roast it --- though I did once find an arrow sticking in the

rump of our neighboring farmer's Guernsey. (She didn't seem to

mind; he was livid.)

I was fixated on a tubby little waterfowl called a moorhen ---

ducks were iffy since they might belong to someone --- but when

moorhens broke cover they ran in crazy evasive patterns and you

couldn't get a bead on them. But failure didn't matter. My

self-image as an intrepid hunter alone in the wilderness, surviving

on my wits, implacably tracking my prey, was reward enough.

I built a succession of secret huts from interwoven reeds and

boughs and grass. I got quite good at siting these in natural

blinds and clumps of vegetation to minimize construction. (Which

made them even more secret.) Nothing better than to sit in the

mouth of a secret reed hut after a hard morning's hunt, a campfire

sizzling in the drizzle, toasting a slice of bread or a sausage and

puffing on a dried, rolled-up dock leaf. Tomorrow, always assuming

I could figure out how to pluck it and gut it, a fat moorhen would

be spitted over this very fire and my entire life would be

fulfilled.

Nobody knew where I was, nobody could find me. I was one with my

allies, the trees and leaves and folds in the earth, the banks and

hedges and stands of wild grass. On fine days the sunlight became a

coconspirator, filtering through the filigree of leaves and

vegetation to make a second, even more secure dimension of dappled

camouflage --- and me even more invisible.

This was when I first came across Marvell's

Annihilating all that's made

To a green thought in a green shade.

No doubt I was creating an alternate or fantasy life (food,

shelter, security) in rejection of the one my parents provided. But

nothing so tediously psychological ever occurred to me. I was happy

without knowing it, at peace long before I knew how crucial and

elusive peace is.

One summer a terrible epidemic called myxomatosis ran through the

entire wild rabbit population, and there were little corpses of my

former prey everywhere, their eyeballs forced halfway out of their

skulls by the jellylike tumors the disease causes, making their

eyes, still staring wildly in death, look like tumors themselves.

There were trophies everywhere, meat for the taking, but I could

only think what a horrible way to die --- for my friends and

coconspirators to die --- and that in some implacable way my

callousness had caused their agony.

Why was all this a doctrinal threat? Because my woods and meadows

seemed a much better church than the Church. The irresistible force

of life --- the tiny eggs appearing in the nest, the buds on the

dead wood of winter --- evidenced a much more immediate presence of

something divine than the presence that was supposed to exist in

the tabernacle on the altar.

There beneath a flickering red lamp that was always lit to indicate

he was home (the Savior is . . . IN) was Christ himself, really

present in the Holy Eucharist, a chalice full of consecrated

wafers. We were taught this was a sacramental presence, the outward

sign of inward grace. The standard exegesis was that while the

outward accidents of the bread did not change at the moment of

consecration, its essence --- that which made it bread and bread

alone --- had been transformed into the essence of Jesus Christ,

that which made him and him alone the son of God. A neat analysis

and, if true, a mind-boggling miracle. The trouble was I felt

nothing gazing up at Christ's little brass hut. No presence at all;

just the exotic odor of last Sunday's incense and that dusty

mushroomy smell of decay all churches have, whatever their

age.

Whereas under my canopy of sun-dappled leaves I certainly felt the

presence of something, and something I was quite prepared to say

was divine, powerful, benign, even loving, and if beyond my ken,

not that far beyond. It could be God or a god, or more likely a

goddess, the spirit of sun-dappled leaves. The lazy River Lea,

polluted though it was, was still a miracle, a whole liquid

universe of life.

One early summer evening, down along the River Lea, following my

best moorhen route, I came upon something I'd never noticed before,

concealed by thick curtains of willow fronds and giant reeds: a

decrepit trailer with saggy old power lines running into the trees,

painted a morose green. In the yard outside, a couple, one with a

baby on her hip, were tending a newly turned garden. I'd come upon

the secret lair of Mr. and Mrs. Mystery --- Ben and Lily

Bootle.

Excerpted from FATHER JOE: The Man Who Saved My Soul ©

Copyright 2011 by Tony Hendra. Reprinted with permission by Random

House, an imprint of PUB2NAME. All rights reserved.

Father Joe: The Man Who Saved My Soul

- Genres: Nonfiction

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Random House Trade Paperbacks

- ISBN-10: 0812972341

- ISBN-13: 9780812972344