Excerpt

Excerpt

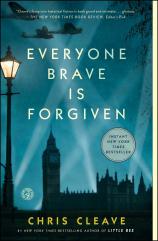

Everyone Brave is Forgiven

WAR WAS DECLARED AT eleven-fifteen and Mary North signed up at noon. She did it at lunch, before telegrams came, in case her mother said no. She left finishing school unfinished. Skiing down from Mont-Choisi, she ditched her equipment at the foot of the slope and telegraphed the War Office from Lausanne. Nineteen hours later she reached St. Pancras, in clouds of steam, still wearing her alpine sweater. The train’s whistle screamed. London, then. It was a city in love with beginnings.

She went straight to the War Office. The ink still smelled of salt on the map they issued her. She rushed across town to her assignment, desperate not to miss a minute of the war but anxious she al- ready had. As she ran through Trafalgar Square waving for a taxi, the pigeons flew up before her and their clacking wings were a thousand knives tapped against claret glasses, praying silence. Any moment now it would start—this dreaded and wonderful thing—and could never be won without her.

What was war, after all, but morale in helmets and jeeps? And what was morale if not one hundred million little conversations, the sum of which might leave men brave enough to advance? The true heart of war was small talk, in which Mary was wonderfully expert. The morning matched her mood, without cloud or equivalence in memory. In London under lucent skies ten thousand young women were hurrying to their new positions, on orders from Whitehall, from chambers unknowable in the old marble heart of the beast. Mary joined gladly the great flow of the willing.

The War Office had given no further details, and this was a good sign. They would make her a liaison, or an attaché to a general’s staff. All the speaking parts went to girls of good family. It was even rumored that they needed spies, which appealed most of all since one might be oneself twice over.

Mary flagged down a cab and showed her map to the driver. He held it at arm’s length, squinting at the scrawled red cross that marked where she was to report. She found him unbearably slow.

“This big building, in Hawley Street?”

“Yes,” said Mary. “As quick as you like.”

“It’s Hawley Street School, isn’t it?”

“I shouldn’t think so. I’m to report for war work, you see.”

“Oh. Only I don’t know what else it could be around there but the school. The rest of that street is just houses.”

Mary opened her mouth to argue, then stopped and tugged at her gloves. Because of course they didn’t have a glittering tower, just off Horse Guards, labeled MINISTRY OF WILD INTRIGUE. Naturally they would have her report somewhere innocuous.

“Right then,” she said. “I expect I am to be made a schoolmistress.”

The man nodded. “Makes sense, doesn’t it? Half the schoolmasters in London must be joining up for the war.”

“Then let’s hope the cane proves effective against the enemy’s tanks.”

The man drove them to Hawley Street with no more haste than the delivery of one more schoolmistress would merit. Mary was careful to adopt the expression an ordinary young woman might wear—a girl for whom the taxi ride would be an unaccustomed extravagance, and for whom the prospect of work as a schoolteacher would seem a thrill. She made her face suggest the kind of sincere immersion in the present moment that she imagined dairy animals must also enjoy, or geese.

Arriving at the school, she felt observed. In character, she tipped the taxi driver a quarter of what she normally would have given him. This was her first test, after all. She put on the apologetic walk of an ordinary girl presenting for interview. As if the air resented being parted. As if the ground shrieked from the wound of each step.

She found the headmistress’s office and introduced herself. Miss Vine nodded but wouldn’t look up from her desk. Avian and cardi- ganed, spectacles on a bath-plug chain.

“North,” said Mary again, investing the name with its significance.

“Yes, I heard you quite well. You are to take Kestrel Class. Begin with the register. Learn their names as smartly as you can.”

“Very good,” said Mary.

“Have you taught before?”

“No,” said Mary, “but I can’t imagine there’s much to it.”

The headmistress fixed her with two wintry pools. “Your imagination is not on the syllabus.”

“Forgive me. No, I have never taught before.”

“Very well. Be firm, give no liberties, and do not underestimate the importance of the child forming his letters properly. As the hand, the mind.”

Mary felt that the “headmistress” was overdoing it, rather. She might mention it to the woman’s superior, once she discovered what outfit she was really joining. Although in mitigation, the woman’s attention to detail was impressive. Here were pots of sharpened pencils, tins of drawing pins. Here was a tidy stack of hymnbooks, each covered in a different wallpaper, just as children really would have done the job if one had tasked them with it in the first week of the new school year.

The headmistress glanced up. “I can’t imagine what you are smirking at.”

“Sorry,” said Mary, unable to keep the glint of communication from her eyes, and slightly flustered when it wasn’t returned.

“Kestrels,” said the headmistress. “Along the corridor, third on the left.”

When Mary entered the classroom thirty-one children fell silent at their hinge-top desks. They watched her, owl-eyed, heads pivoting from the neck. They might be eight or ten years old, she supposed— although children suffered dreadfully from invisibility and required a conscious adjustment of the eye in order to be focused on at all.

“Good morning, class. My name is Mary North.”

“Good morning Miss North.”

The children chanted it in the ageless tone exactly between deference and mockery, so perfectly that Mary’s stomach lurched. It was all just too realistic.

She taught them mathematics before lunch and composition after, hoping that a curtain would finally be whisked away; that her audition would give way to her recruitment. When the bell rang for the end of the day she ran to the nearest post office and dashed off an indignant telegram to the War Office, wondering if there had been some mistake.

There was no mistake, of course. For every reproach that would be laid at London’s door in the great disjunction to come—for all the convoys missing their escorts in fog, for all the breeches shipped with mismatched barrels, for all the lovers supplied with hearts of the wrong calibre—it was never once alleged that the grand old capital did not excel at letting one know, precisely, where one’s fight was to begin.

September, 1939

MARY ALMOST WEPT WHEN she learned that her first duty as a schoolmistress would be to evacuate her class to the countryside. And when she discovered that London had evacuated its zoo animals days before its children, she was furious. If one must be exiled, then at least the capital ought to value its children more highly than ma- caws and musk oxen.

She checked her lipstick in a pocket mirror, then raised her hand.

“Yes, Miss North?”

“Isn’t it a shame to evacuate the animals first?”

She said it in full hearing of all the children, who were lined up at their muster point outside the empty London Zoo, waiting to be evacuated. They gave a timid cheer. The headmistress eyed Mary coolly, which made her doubt herself. But surely it was wrong to throw the beasts the first lifeline? Wasn’t that the weary old man’s choice Noah had made: filling the ark with dumb livestock instead of lively children who might answer back? This was how the best roots of humanity had drowned. This was why men were the violent in-breds of Ham and Shem and Japheth, capable of declaring for war a season that Mary had earmarked for worsted.

The headmistress only sighed. So: the delay was simply because one did not need to write a marmoset’s name on a luggage tag, ac- company it in a second-class train compartment and billet it with a suitable host family in the Cotswolds. The lower primates only wanted a truck for the trip and a good feed at the other end, while the higher hominidae, with names like Henry and Sarah, had a multiplicity of needs that a diligent bureaucracy had not only to anticipate but also to meet, and furthermore to document, on forms that must first come back from the printer.

“I see,” said Mary. “Thank you.”

Of course it was that. She hated being eighteen. The insights and indignations burned through one’s good sense like hot coals through oven gloves. So, this was why London still teemed with children while London Zoo stood vacant, with three hundred halfpenny portions of monkey nuts in their little twists of newspaper waiting un- sold and forlorn in the kiosk.

She raised her hand again, then let it drop.

“Yes?” said Miss Vine. “Was there something else?”

“Sorry,” said Mary. “It was nothing.”

“Oh good.”

The headmistress took her eye off the ranks of the children for a moment. She fixed Mary with a look that was not without charity. “Remember you’re on our side now. You know: the grown-ups.”

Mary could almost feel her bones cracking with resentment. “Thank you, Miss Vine.”

This was when the school’s only colored child, sensing an open- ing, slipped away from the muster and scaled the padlocked main gate of the zoo. The headmistress spun around. “Zachary Lee! Come back here immediately!”

“Or what? You’ll send me to the countryside?”

The whole school gasped. Ten years old, invincible, the Negro boy saluted. He scissored his skinny brown legs over the top of the gate, using the penultimate and the ultimate wrought-iron O’s of LON- DON ZOO as the hoops of a pommel horse, and was immediately lost to sight.

Miss Vine turned to Mary. “You had better bring the nigger back, don’t you think?”

—

It was her first rescue work of the war. Coppery, coltish Mary North searched the abandoned zoo using paths that were still well tended. On her own, she felt better. She sneaked a cigarette. She massaged her brow with the other hand, confident that frustration could be persuaded not to settle there. All downers could be dispatched, as one might flick ash off one’s sleeve, or pilot a wayward bee back out through an open window.

She had already checked the giraffes’ paddock and the big cats’ dens. Now, hearing a cough, she tiptoed into the great apes’ enclosure through a gate that swung unlatched. She kicked through the straw, raising a scent of urine and musk that made her heart rattle with fright. But she hoped it was not easily done, for a zookeeper to miss a whole gorilla when he was counting them into the evacuation truck.

“Come on out, Zachary Lee, I know you’re in here.”

It was eerie to be in the gorilla house, looking out through the smeared glass. “Oh do come on, Zachary darling. You’ll get us both in trouble.”

A second cough, and a rustle under the straw. Then, with his soft American accent, “I’m not coming out.”

“Fine then,” said Mary. “The two of us shall rot here until the war is over, and nobody will ever know what talent we might have shown in its prosecution.”

She sat down beside the boy, first laying her red jacket on the straw to sit on, with the rosy silk lining downward. It was hard to stay glum. One could say what one liked about the war but it had got her out of Mont-Choisi ahead of an afternoon of double French, and might yet have more mercies in store. She lit another cigarette and blew the smoke into a shaft of sunlight.

“May I have one?” said the small voice.

“Beautifully asked,” said Mary. “And no. Not until you are eleven.”

From the muster point came the sound of a tin whistle. It could mean that heavy bombers were converging on London, or it could mean that the children had been organized into two roughly matched teams to begin a game of rounders.

Zachary poked his head up through the straw. It still amazed Mary to see his brown skin, his chestnut eyes. The first time he had smiled, the flash of his pink tongue had delighted her. She had imag- ined it would be—well, not brown also, but certainly as antithetical to pink as brown skin was to white. A bluish tongue, perhaps, like a skink’s. It would not have surprised her to learn that his blood came out black and his feces a pale ivory. He was the first Negro she had seen up close—if one didn’t count the posters advertising minstrelsy and coon shows—and she still struggled not to gawk.

The straw clung to his hair. “Miss?’ he said. “Why did they take the animals away?”

“Different reasons in each case,” said Mary, counting them off on her fingers. “The hippopotami because they are such frightful cowards, the wolves since one can never be entirely sure whose side they are on, and the lions because they are to be parachuted directly into Berlin Zoo to take on Herr Hitler’s big cats.”

“So the animals are at war too?”

“Well of course they are. Wouldn’t it be absurd if it were just us?”

The boy’s expression, suggesting that he had not previously taken the matter under consideration.

“What are two sevens?” asked Mary, taking advantage.

The boy began his reckoning, in the deliberate and dutiful manner of a child who intended to persevere at least until he ran out of fingers. Not for the first time that week, Mary suppressed both a smile and a delightful suspicion that teaching might not be the worst way to spend the idle hours between breakfast and society.

On Tuesday morning, after taking the register and before distributing milk in little glass bottles, Mary had written the names of her thirty-one children on brown luggage labels and looped them through the top buttonholes of their overcoats. Of course the children had exchanged labels with one another the second her back was turned. They were only human, even if they hadn’t yet made the effort to become tall.

And of course she had insisted on calling them by their ex- changed names—even for boys named Elaine and girls named Peter— while maintaining an entirely straight face. It delighted her that she could make them laugh so easily. It turned out that the only difference between children and adults was that children were prepared to put twice the energy into the project of not being sad.

“Is it twelve?” said Zachary. “Is what twelve?”

“Two sevens,” he reminded her, in the exasperated tone reserved for adults who asked questions with no thought to the expenditure of emotion that went into answering.

Mary nodded her apology. “Twelve is jolly close.”

The tin whistle, sounding again. Above the enclosures, seagulls wheeled in hope. The memory of feeding time persisted. Mary felt an ache. All the world’s timetables fluttered through blue sky now, va- grant on the winds.

“Thirteen?”

Mary smiled. “Would you like me to show you? You’re a bright boy but you’re ten years old and you are miles behind with your numbers. I don’t believe anyone can have taken the trouble to teach you.”

She knelt in the straw, took his hands—it still amazed her that they were no hotter than white hands—and showed him how to count forward seven more, starting from seven. “Do you see now? Seven, plus seven more, is fourteen. It is simply about not stopping.”

“Oh.”

The surprised and disappointed air boys had when magic yielded so bloodlessly to reason.

“So what would be three sevens, Zachary, now you have two of them already?”

He examined his outstretched fingers, then looked up at her. “How long?” he said.

“How long what?”

“How long are they sending us away for?”

“Until London is safe again. It shouldn’t be too long.”

“I’m scared to go to the country. I wish my father could come.”

“None of the parents can come with us. Their work is vital for

the war.”

“Do you believe that?”

Mary shook her head briskly. “Of course not. Most people’s work is nonsense at the best of times, don’t you think? Actuaries and loss adjusters and professors of Eggy-peggy. Most of them would be more useful reciting limericks and stuffing their socks with glitter.”

“My father plays in the minstrel show at the Lyceum. Is that useful?”

“For morale, certainly. If minstrels weren’t needed I daresay they’d have been evacuated days ago. On a gospel train, don’t you think?”

The boy refused to smile. “They won’t want me in the country- side.”

“Why on earth wouldn’t they?”

The pained expression children had, when one was irredeemably obtuse.

“Oh, I see. Well, I daresay they will just be awfully curious. I sup- pose you can expect to be poked and prodded a little, but once they understand that it won’t wash off I’m sure they won’t hold it against you. People are jolly fair, you know.”

The boy seemed lost in thought.

“Anyway,” said Mary, “I’m coming to wherever-it-is we’re going. I promise I shan’t leave you.”

“They’ll hate me.’

“Nonsense. Was it minstrels who invaded Poland? Was it a troupe of theater Negroes who occupied the Sudetenland?”

He gave her a patient look.

“See?” said Mary. “The countryside will prefer you to the Germans.”

“I still don’t want to go.”

“Oh, but that’s the fun of it, don’t you see? It’s a simply enormous game of go-where-you’re-jolly-well-told. Everyone who’s any- one is playing.”

She was surprised to realize that she didn’t mind it at all, being sent away. It really was a giant roulette—this was how one ought to see it. The children would get a taste of country air, and she . . . well, what was the countryside if not numberless Heathcliffs, loosely tethered?

Let us imagine, she thought, that this war will surprise us all. Let us suppose that the evacuation train will take us somewhere wild, far from these decorous streets where every third person has an anecdote about my mother, or votes in my father’s constituency.

She imagined herself in the country, in a pretty village of vivid young people thrown into a new pattern by the war. It would be like the turning of a kaleidoscope, only with gramophones and dancing. Just to show her friend Hilda, she would fall in love with the first man who was even slightly interesting.

She squeezed the colored boy’s hand, delighted by his smile as her bright mood made the junction. “Come on,” she said, “shall we get back to the others before they have all the fun?”

They stood up from the straw and she brushed the child down. He was a bony, startle-eyed thing—giving the impression of being thoroughly X-rayed—with an insubordinate crackle of black hair. She shook her head, laughing.

“What?”

“Zachary Lee, I honestly don’t know why we bother evacuating you. You look as if you’ve been bombed already.”

He scowled. “Well, you smoke like this.”

He gave his impression of Mary smoking like Bette Davis, as if the burning Craven “A” generated a terrific amount of lift. The cigarette, straining to rise, straightened the wrist nicely and lifted the first and second fingers into the gesture of a bored saint offering benediction.

“Yes, that’s it!” said Mary. “But do show me how you would do it.”

Slick as a magician palming a penny, Zachary flipped the imaginary cigarette around so that the cherry smoldered under the cup of his hand. He cut wary eyes left and right, drew deeply and then, averting his face, opened a small gap in the corner of his mouth to jet smoke down at the straw. The exhalation was almost invisibly quick, a sparrow shitting from a branch.

“Good lord,” said Mary, “you smoke as if the world might tell you not to.”

“I smoke like a man,” said the child, affecting weariness.

“Well then. Unless one counts the three Rs, I don’t suppose I have anything to teach you.”

She took his arm and they walked together—he wondering whether the lions would be dropped on Berlin by day or by night and she replying that she supposed by night, since the creatures were mostly nocturnal, although in wartime, who knew?

They rotated through the exit turnstile. Mary made the boy to go first, since it would be too funny if he were to abscond again, with her already through to the wrong side of the one-way ratchet. If their roles had been reversed, then she would certainly have found the possibility too cheerful to resist.

On the grass they found the school drawn up into ranks, three by three. She kept Zachary’s arm companionably until the headmistress shot her a look. Mary adjusted her grip to be more suggestive of restraint.

“I shall deal with you later, Zachary,” said Miss Vine. “As soon as I am issued with a building in which to detain you, expect to get detention.”

Zachary smiled infuriatingly. Mary hurried him along the ranks until they came to her own class. There she took plain, sensible Fay George from her row and had her form a new row with the recaptured escapee, instructing her to hold his hand good and firmly. This Fay did, first taking her gloves from the pocket of her duffel coat and putting them on. Zachary accepted this without comment, looking directly ahead.

The headmistress came to where Mary stood, twitched her nose at the smell of cigarette smoke, and glanced pointedly heavenward. As if there might be a roaring squadron of bombers up there that Mary had somehow missed. Miss Vine took Zachary by the shoulders. She shook him, absentmindedly and not without affection. It was as if to ask: Oh, and what are we to do with you?

She said, “You young ones have no idea of the difficulties.”

Mary supposed that she was the one being admonished, although it could equally have been the child, or—since her headmistress was still looking skyward—it might have been the youthful pilots of the Luftwaffe, or the insouciant cherubim.

Mary bit her cheek to keep from smiling. She liked Miss Vine—the woman was not made entirely of vipers and crinoline. And yet she was so boringly wary, as if life couldn’t be trusted. “I am sorry, Miss Vine.”

“Miss North, have you spent much time in the country?”

“Oh yes. We have weekends in my father’s constituency.”

It was exactly the sort of thing she tried not to say.

Miss Vine let go of Zachary’s shoulders. “May I borrow you for a moment, Miss North?”

“Please,” said Mary.

They took themselves off a little way.

“What inspired you to volunteer as a schoolmistress, Mary?”

Pride would not let her reply that she had not volunteered for anything in particular—that she had simply volunteered, assuming the issue would be decided favourably, as it always had been until now, by influences unseen.

“I thought I might be good at teaching,” she said.

“I’m sorry. It is just that young women of your background usually wouldn’t consider the profession.”

“Oh, I shouldn’t necessarily see it like that. Surely if one had to pick a fault with women of my background, it might be that they don’t consider work very much at all.”

“And, dear, why did you?”

“I hoped it might be less exhausting than the constant rest.”

“But is there no war work that seems to you more glamorous?”

“You do not have much faith in me, Miss Vine.”

“But you are impossible, don’t you see? My other teachers are dazzled by you, or disheartened. And you are overconfident. You be- friend the children, when it is not a friend that they need.”

“I suppose I just like children.”

The headmistress gave her a look of undisguised pity. “You can- not be a friend to thirty-one children, all with needs greater than you imagine.”

“I think I understand what is needed.”

“You have been doing the job for four days, and you think you understand. The error is a common one, and harder to correct in young women who have no urgent use for the two pounds and seven- teen shillings per week.”

Mary bristled, and with an effort said nothing.

“All the trouble this week has come from your class, Mary. The tantrums, the mishaps, the abscondments. The children feel they can take liberties with you.”

“But I feel for them, Miss Vine. Saying goodbye to their parents for who knows how long? The state they are in, I thought perhaps a little license—”

“Could kill them. I have no idea what these next few weeks or months will bring, but I am certain that if there is violence then we shall need to have every child accounted for at all times, ready to be taken to shelter at a moment’s notice. They mustn’t be who-knows- where.”

“I am sorry. I will improve.”

“I fear I cannot risk giving you the time.”

“Excuse me?”

“At noon, Mary, we are to proceed on foot to Marylebone, to board a train at one. They have not given me the destination, al- though I imagine it must be Oxfordshire or the Midlands.”

“Well, then . . .”

“Well, I am afraid I shan’t be taking you along.”

“But Miss Vine!”

The headmistress put a hand on her arm. “I like you, Mary. Enough to tell you that you will never be any good as a teacher. Find something more suited to your many gifts.”

“But my class . . .”

“I will take them myself. Oh, don’t look so sick. I have done a little teaching in my time.”

But their names, thought Mary. I have learned every one of their names.

She stood for a moment, concentrating—as her mother had taught her—on keeping her face unmoved. “ ‘Very well.”’

“You are a credit to your family.”

“Not at all,” said Mary, since that was what one said.

Noon came too quickly. She retrieved her suitcase from the trolley where the rest of the staff had theirs, and watched the school evacuate in rows of three down the Outer Circle Road. Kestrels went last: her thirty-one children with their names inscribed on brown baggage tags. Enid Platt, Edna Glover and Margaret Eccleston made up the front row, always together, always whispering. For four days now their gossip had seemed so thrilling that Mary had never known whether to shush them or beg to be included.

Margaret Lambie, Audrey Shepherd and Nellie Gould made up the next row: Audrey with her gas-mask box decorated with poster paint, Nellie with her doll who was called Pinkie, and Margaret who spoke a little French.

Mary was left behind. The green sward of grass beside the abandoned zoo became quiet and still. George Woodall, Jack Taylor and Graham Brown marched with high-swinging arms in the infantry style. John Cumberland, Harry Rogers and Carl Richardson mocked them with chimpanzee grunts from the row behind. Henriette Wisby, Elaine Newland and Beryl Waldorf, the beauties of the class, sashayed with their arms linked, frowning at the rowdy boys. Then Eileen Robbins, Norma Reeve and Rose Montiel, pale with apprehension.

Next went Patricia Fawcett, Margaret Taylor and June Knight, whose mothers knew one another socially and whose own eventual daughters and granddaughters seemed sure to prolong the acquaintance for so long as the wars of men permitted society to convene over sponge cake and tea. Then Patrick Joseph, Gordon Abbott and James Wright, giggling and with backward glances at Peter Carter, Peter Hall and John Clark, who were up to some mischief that Mary felt sure would involve either a fainting episode, or ink.

Finally came kind Rita Glenister supporting tiny, tearful James Roffey, and then, in the last row of all, Fay George and Zachary. The colored boy dismissed Mary by taking one last puff of his imaginary cigarette and flicking away the butt. He turned his back and walked away with all the others, singing, toward a place that did not yet have a name. Mary watched him go. It was the first time she had broken a promise.

—

At dinner, at her parents’ house in Pimlico, Mary sat across from her friend Hilda while her mother served slices of cold meatloaf from a salver that she had fetched from the kitchen herself. With Mary’s father off at the House and no callers expected, her mother had given everyone but Cook the night off.

“So when are you to be evacuated?” said her mother. “I thought you’d be gone by now.”

“Oh,” said Mary, “I’m to follow presently. They wanted one good teacher to help with any stragglers.”

“Extraordinary. We didn’t think you’d be good, did we, Hilda?”

Hilda looked up. She had been cutting her slice of meatloaf into thirds, sidelining one third according to the slimming plan she was following. Two Thirds Curves had been recommended in that month’s Silver Screen. It was how Ann Sheridan had found her figure for An- gels with Dirty Faces.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. North?”

“We didn’t suppose Mary would be any use at teaching, did we, dear?”

Hilda favored Mary with an innocent look. “And she was so stoical about the assignment.”

Hilda knew perfectly well that she had neither volunteered accepted the role particularly graciously nor survived in it for a week. Mary managed a smile that she judged to have the right inflection of modesty. “Teaching helps the war effort by freeing up able men to serve.”

“I had you down for freeing up some admiral.”

“Hilda! Any more talk like that and your severed head on the gate will serve as a warning to others.’

“I’m sorry, Mrs. North. But a pretty thing like Mary is hardly cut out for something so plain as teaching, is she?”

Hilda knew perfectly well that Mary was already suspected by her mother of dalliances. This was typical her: baiting the most exquisite trap and then springing it, while all the while seeming to have most of her mind on her meatloaf.

“I’m just jolly impressed that she’s sticking with it,” said Hilda. “I can’t even stick to a diet.”

With unbearable ponderousness, she was using her knife and fork to reduce the length of each of the runner beans on her plate by one third. With perfect diligence she lined up each short length be- side the surplus meatloaf.

Mary rose to it. “Why on earth are you cutting them all like that?”

Hilda’s round face was guileless. “Are my thirds not right?”

“Just put aside one bean in three, for heaven’s sake. It’s dieting,

not dissection.”

Hilda slumped. “I’m not as bright as you.”

Mary threw her a furious look. Hilda’s dark eyes glittered.

“We have different gifts,” said Mary’s mother. “You are faithful and kind.”

“But I think Mary is so brave to be a teacher, don’t you? While the rest of us only careen from parlor to salon.”

Mary’s mother patted her hand. “We also serve who live with grace.”

“But to do something for the war,” said Hilda. “To really do something.”

“I suppose I am proud of my daughter. And only this summer we were worried she might be a socialist.”

And finally all three of them laughed. Because really.

—

After dinner, on the roof terrace that topped the six stories of creamy stucco, with the two of them in white dresses flaming red as the sun set over Pimlico, Hilda was weak with laughter while Mary seethed.

“You perfect wasp’s udder,” said Mary, lighting a cigarette. “Now I shall have to pretend forever that I haven’t been sacked. Was all that about Geoffrey St John?”

“Why would you imagine it was about Geoffrey St John?”

“Well, I admit I might have slightly . . .”

“Go on. Have slightly what?”

“Have slightly kissed him.”

“At the . . . ?”

“At the Queen Charlotte’s Ball.”

“Where he was there as . . .”

“As your escort for the night. Fine.”

“Interesting.’

“Isn’t it?” said Mary. “Because apparently you are still jolly furious.”

“So it would seem.”

Mary leaned her elbows on the balcony rail and gave London a weary look. “It’s because you’re not relaxed about these things.”

“I’m very traditional,” said Hilda. “Still, look on the bright side. Now you have a full-time teaching job.”

“You played Mother like a cheap pianola.”

“And now you will have to get your job back, or at least pretend. Either way you’ll be out of my hair for the Michaelmas Ball.”

“The ball, you genius, is to be held after school hours.”

“But you will have to be in the countryside, won’t you? Even your mother will realize that there’s nobody here to teach.”

Mary considered it. “I will get you back for this.”

“Eventually I shall forgive you, of course. I might even let you come to my wedding to Geoffrey St John. You can be a bridesmaid.”

They leaned shoulders sociably and watched the darkening city.

“What was it like?” said Hilda finally.

Mary sighed. “The worst thing is that I loved it.”

“But I did see him first, you know,” said Hilda.

“Oh, I don’t mean kissing Geoffrey. I mean I loved the teaching.”

“What are you cooking up now?”

“No, really! I had thirty-one children, bright as the devil’s cuff links. Now they’re gone it feels rather dull.”

The blacked-out city lay inverted. Until now it had answered the evening stars with a million points of light, drowning them in extroversion.

“Why not the kiss?” said Hilda after a while. “What was wrong with Geoffrey’s kiss anyway?”

Everyone Brave is Forgiven

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 448 pages

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- ISBN-10: 1501124382

- ISBN-13: 9781501124389