Excerpt

Excerpt

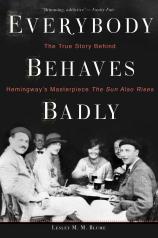

Everybody Behaves Badly: The True Story Behind Hemingway's Masterpiece The Sun Also Rises

Introduction

In March 1934, Vanity Fair ran a mischievous editorial: a page of Ernest Hemingway paper dolls, featuring cutouts of various famous Hemingway personas. On display: Hemingway as a toreador, clinging to a severed bull’s head; Hemingway as a brooding, café-dwelling writer (four wine bottles adorn his table, and a waiter is seen toting three more in his direction); Hemingway as a bloodied war veteran. “Ernest Hemingway, America’s own literary cave man,” declared the caption. “Harddrinking, hard-fighting, hard-loving — all for art’s sake.”

Throughout his life, additional personas would attach themselves to him: rugged deep-sea fisherman; big-game hunter; postwar liberator of the Paris Ritz; white-bearded Papa. He relished all of these identities and so did the press. When it came to selling copy, Hemingway was one of America’s most versatile leading men, and certainly one of the country’s most fascinating entertainers.

By then, everyone had long forgotten one of his earliest roles: unpublished nobody. It was one of the few Hemingway personas that never really suited him. In fact, in the early 1920s — strapped for cash, ravenous for recognition — he was frantic to rid himself of it. Even in the earliest days of his career, his ambition seemed limitless. Unfortunately for him, the literary gatekeepers proved uncooperative at first. Hemingway was ready to dominate the world of letters, but its citizens were not yet willing to succumb. Mainstream publications turned down his short stories; his rejected manuscripts came back to him and were shoveled through the mail slot in his apartment’s front door.

“The rejection slip is very hard to take on an empty stomach,” Hemingway later told a friend. “There were times when I’d sit at that old wooden table and read one of those cold slips that had been attached to a story I Introduction x Introduction had loved and worked on very hard and believed in, and I couldn’t help crying.”

During such moments of despair, it is unlikely that Hemingway realized that he was actually one of the luckier writers in modern history. Circumstances often seemed to conspire in his favor. All of the right things made their way to him at the right moment: motivated mentors, publisher patrons, wealthy wives — and a trove of material just when he needed it most, in the form of some delectably bad behavior among his peers, which he promptly translated into his groundbreaking debut novel, The Sun Also Rises, published in 1926. In the book’s pages, those co-opted antics — benders, hangovers, affairs, betrayals — took on a new and loftier guise of their own: experimental literature. Thus elevated, all of this bad behavior rocked the literary world and came to define Hemingway’s entire generation.

Everyone knows how this story ends: to say that Hemingway eventually became famous and successful is a gross understatement. A Nobel laureate, he has been widely called the father of modern literature and for decades has been read in dozens of languages around the globe. More than half a century after his death, he still commands headlines and crops up in gossip columns.

What follows is the story of how Hemingway became Hemingway in the first place — and the book that set it all in motion. The backstory of The Sun Also Rises and that of its author’s rise are one and the same. Critics have long cited Hemingway’s second novel, A Farewell to Arms, as the one that established him as a giant in the literary pantheon, but in many ways, the significance of The Sun Also Rises is much greater. As far as literature was concerned, it essentially introduced its mainstream readers to the twentieth century.

“The Sun Also Rises did more than break the ice,” says Lorin Stein, editor of the Paris Review. “It was modern literature fully arrived for a grand public. I’m not sure that there was ever another moment when one novelist was so obviously the leader of a whole generation. You read one sentence and it doesn’t sound like anything that came before.”

Not that there weren’t other tremors before this earthquake. A small movement of writers had been trying to shove literature out of musty Edwardian corridors and into the fresh air of the modern world. It was a question of who would break through first — and who could make new ways of writing appealing to the mainstream reader, who, for the most part, still seemed to be perfectly satisfied with the more florid, verbose approaches of Henry James and Edith Wharton. James Joyce’s radical novel Ulysses, for example, had blown the minds of many postwar writers.

But at first the work was hardly a mainstream sensation: it wasn’t even released in book form in the United States until the 1930s. Paris-based experimentalist Gertrude Stein had resorted to self-publishing her works, which were often deemed incomprehensible by those who actually did read them. One of her books reportedly sold a mere seventy-three copies in its first eighteen months of existence. F. Scott Fitzgerald had also been striving to reinvent the American novel and felt that he had succeeded with the publication of The Great Gatsby in 1925. Yet while the content of his novels was thoroughly modern — flappers, bootleggers, and other exotic urban creatures — his style remained decidedly old-school.

“Fitzgerald was a nineteenth-century soul,” says Charles Scribner III, a former director at Charles Scribner’s Sons, which published both Fitzgerald and Hemingway for the majority of their careers. “[He] was wrapping up a grand tradition; he was the last of the romantics. He was Strauss.”

Hemingway, by contrast, was Stravinsky.

“He was inventing a whole new idiom and tonality,” explains Scribner. “And he was completely twentieth century.” As one prominent critic noted around that time, Hemingway succeeded in doing for writing what Picasso and the cubists had been doing for painting: after the debut of the “primitive modern idiom” of cubism and Hemingway’s stark, staccato prose, nothing would ever be the same again. Modernity had found its popular creative leaders.

The Sun Also Rises immediately established Hemingway not only as the voice of his generation but as a lifestyle icon as well. Before the novel’s debut, Fitzgerald had been doing most of the talking. In those days, novelists had quite a national platform. Movies were still a relatively new medium; TV was decades away. Novels and stories were a major form of popular entertainment. Fitzgerald had become a national celebrity; his new works were devoured and discussed as the finale of a beloved television show — such as The Sopranos or Mad Men — might be rhapsodized about today. Yale students flocked to the New Haven railroad station when trains bearing magazines with his latest stories were due to arrive.

From Fitzgerald’s point of view, however, that generation was a decadent, champagne-soaked constituency. The Great Gatsby became the bible of the Jazz Age — which Fitzgerald himself had done much to invent. If he was seen as an apt chronicler of his times, he also prompted life to imitate art: many fashioned themselves after Fitzgerald’s racy characters — and after Fitzgerald and his flapper wife, Zelda, themselves.

“Scott gave the era a tempo,” Zelda wrote years later, “and a plot from which it might dramatize itself.”

Hemingway’s debut novel changed that tempo considerably. With the publication of The Sun Also Rises, his generation was informed that it was not giddy after all. Rather, it was simply lost. The Great War had ruined everyone, so everyone might as well start drinking even more heavily — and preferably in Paris. Back in America, the college set gleefully adopted the label of the “Lost Generation,” a term that Hemingway borrowed from Gertrude Stein and popularized with his novel. The Sun Also Rises essentially became the new guidebook to contemporary youth culture. Parisian cafés teemed with Sun character wannabes: the hard-drinking Jake Barnes and the studiously blasé Lady Brett Ashley were suddenly trendy role models. Many generational movements would follow — the Beats, Generation X, the Millennials — yet none has been as romanticized as this pioneering youth movement, which for many still shimmers with dissipated glamour.

And at the time, no one seemed a better representative of that chic lost world than Hemingway himself, thanks to the public relations machine that plugged him as a personality along with Sun. Those charged with marketing Hemingway’s work were aware of their good fortune: in a sense, they were getting two juicy stories for the price of one. It quickly became apparent that the public’s appetite for Hemingway himself was as great as that for his writing, and he and his team were quite happy to oblige them. Here was a new breed of writer — brainy yet brawny, a far cry from Proust and his dusty, sequestered ilk. Almost immediately upon the release of The Sun Also Rises, at least one press outlet noted the emergence of a Hemingway “cult” on two continents.

Everybody Behaves Badly: The True Story Behind Hemingway's Masterpiece The Sun Also Rises

- Genres: Biography, History, Nonfiction

- paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: Eamon Dolan/Mariner Books

- ISBN-10: 0544944437

- ISBN-13: 9780544944435