Excerpt

Excerpt

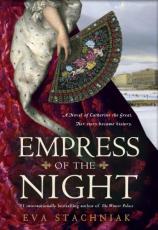

Empress of the Night: A Novel of Catherine the Great

9:00 a.m.

The pain is sharp, piercing, a burning dagger’s thrust inside her skull, somewhere behind the right eye. It hits just as she lifts her quill out of an inkwell. Her hand freezes. The quill, dropped, stains the letter she was just about to sign.

The mantel clock begins to chime. She recalls being frightened as a child to see the hands of a clock turned back, believing time itself might go back and she would be forced to live again through everything she had already lived through, depriving her of the adventure of the future.

The pain doesn’t stop or diminish. It is already nine o’clock and she is still behind with the reading she must finish before her secretary arrives. She considers calling Zotov, her valet, but dismisses the thought quickly. The headache will go away by itself, but once her old servant begins to fuss, she won’t be able to send him away.

Pani, her Italian greyhound, sniffs her mistress’s hand with fierce concentration, licking the skin of her palm. The dog is slender and fine-boned, a direct descendant of beloved Zemira, who lies buried in the Tsarskoye Selo gardens.

“I’ve nothing for you there,” she mutters. She tries to pat Pani’s head, but her right hand is strangely wooden, stiff and unwieldy, so she settles for an awkward caress, noting thick drops of pus in the corners of her dog’s eyes. Just like Zemira, Pani is prone to lingering infections.

Outside her study, pattering feet and muted voices dissolve into furtive silence: The Empress is working. The Empress must not be disturbed.

She stands. With her left hand she grips the edge of her desk, clumsily, sending the papers flying. How intriguing, she thinks, watching the vellum pages glide on invisible currents, hover in the air, silent like birds of prey. Pani, too, watches, head cocked to the side. A wagging tail thumps at the floor.

The cup of coffee on the desk must be cold by now, but a drink will do her good. Her right hand is still heavy and stiff, so she picks up the cup with her left. The first bitter sip is refreshing, but the second one makes her choke.

She spits the coffee out. On the encrusted wood, on her papers. Brown, watery splashes she should wipe right away, but instead she lets her tongue probe the inside of her mouth, the soft, ribbed folds of her palate. Like calf’s brain, she thinks, her mother’s favorite dish.

She tries to put the cup back on the desk, but her hand refuses to obey, and it shatters on the floor.

If she walks a bit, will the headache dissolve?

Her first step is wobbly, unsure, making her clutch whatever is within her reach. The corner of her desk, the chair.

Behind her something falls down. Something big and heavy.

Her right knee is still sore. It’s been like this ever since that dreadful fall three years ago, when she toppled down the stairs on her way to the banya. Zotov had heard the noise and rushed after her. Made her sit on the marble step for a while. Only when she assured him the dizzy spell had passed did he help her stand up, slowly. She didn’t think she had been truly hurt, bruised and frightened as she was, but the knee is not letting her forget the fall.

9:01 a.m.

Each step, unsteady as it is, is a marvel. The muscles contracting and releasing. The feet shuffling forward, one after another. Like the mechanical doll her granddaughters loved to play with, before Constantine, her grandson, cut it open to see what was hidden inside.

The steps take her out of her study, past the small alcove where her pelisses hang beside the silver-framed mirror, toward the door that leads to her privy.

In the alcove mirror, her body is reflected as if in quivering water, broken into uneven, ill-fitting parts, each wrinkled and malformed. Her face fares no better, the sagging flesh, the neck that resembles a turkey’s throat. Her eyes are bloodshot, watery, blinking. I’ve never been beautiful, she thinks. But what did Helen of Troy have to show for her looks? The ravages of war and the pursuit of men she had not chosen?

The privy smells, faintly, of wet animal fur and rotting roots. The door closes behind her with a thump. The squeak of the hinges is oddly sharp, circling around her like the sound of a tuning fork. As if time looped, refusing to unravel.

Her fingers gripping the edge of the water closet resemble claws of some ancient bird, not quite accustomed to such feats of agility. And yet they hold on, help her balance. How magnificent, she thinks, this effort of muscles and bones, sinew and blood.

Slowly she lifts the fingertips to her nostrils and sniffs at the sweet, sharp smell of ink. Something from the past floats by—images of a race, frothy waves crashing against the shore, stretching over tawny sand. Seagulls shriek out of jealousy or greed. In the shallow water a horse’s head lies entangled in a tattered fishnet and tufts of seaweed, baring its teeth. A swarm of eels wiggles out of its eye sockets, slithers through its open jaws.

A memory, she thinks, not a dream.

9:04 a.m.

With the headache pounding in her temples, voices bubble inside her. Phrases echo in her mind: I am Minerva. I am armed.

Something odd is happening.

A thought is not just a thought. A word is not a mere word.

She thinks of an apple and an apple appears. It is slightly greasy to the touch. It has plump, sunburnt sides and a splash of green around the stem bowl. Its skin is freckled with darker spots.

She stares at it for a while before setting her teeth on the skin and pressing hard. The apple snaps off with a cracking sound, then shatters, filling her mouth with juice.

The joy she feels is ancient, the joy of crushing through living tissue, life nourishing life.

Why am I thinking about an apple?

There is no apple. Her hand is empty. The word apple that rattles in her mind means temptation.

Is this what she should be thinking of?

The question intrigues her for a while, until another agonizing throb shoots up the right side of her skull and a flash of light stings her eyes.

9:05 a.m.

In the vestibule, servants talk.

“Are you sure Her Majesty hasn’t called for me yet?” Gribovsky asks. Her secretary’s voice is anxious, thin with unease.

“Quite sure, Adrian Moseyevich.”

“But it’s past the usual time.”

“Her Majesty has her reasons.”

Something is happening to her, but she has little time to think what it might be. Each movement demands her utmost attention, angles to calculate and adjust, muscles to flex and to steady. She listens to each breath that enters or leaves her nostrils.

Her heart, a traitor drummer, pounds its own rhythm. Or is it like a frantic courtier sent to warn her of some approaching calamity? Fire? Flood? The mob armed with scythes, marching on the palace doors?

Her lips are parched. The blue porcelain jug in the privy is too heavy to lift, so she dips her fingers inside and sucks on the drops that cling to them. The water is stale. She should ring for Queenie, who must be outside, with the others.

Why is there no bell in the privy?

The headache has diminished, but the inside of her skull feels fragile and exposed, as if an ax has split her open. Is this how Jupiter felt giving birth to Minerva?

“What time is it?”

“Still early, Adrian Moseyevich,” someone answers curtly. A woman laughs. A door opens and closes. Footsteps grow fainter. A dog barks. Something rattles against the windowpane; there is a loud bang followed by a thump.

“You know who he is. His father ran a bookstore off the Great Perspective Road. By the Fontanka. Then it got flooded.”

“What are you scribbling there, Adrian Moseyevich? Have some hot tea. It’s a chilly morning.”

“The dog is still missing. Do you think someone stole it?”

“A thief would’ve brought it back, already, for the reward.”

“The poor beastie must be dead by now.”

The voices outside the privy door float back and forth; whispers fade away. Rumbles quicken like wooden carts on the ice mountain, right before they pick up real speed and become unstoppable.

9:09 a.m.

In the privy, she manages to hike up her petticoats and lower herself on the commode seat. Like a big hen settling onto a nest. The seat is cold and sticky, giving way under her weight with a squeak.

The voices in the vestibule swirl, punctuated by moments of soothing silence. The world around her slows. The pain is still there, but it, too, feels distant, easier to bear. Time is sluggish. There is no need to rush.

Inside her belly, muscles let go, release the hot stream of urine. For a while, all she wants to do is sit and absorb the profound pleasure of relief. Sink into silence. Just be.

Out of this silence comes another memory. A monkey, Plaisir, was the French Ambassador’s gift. A mere baby when he came, dressed in a velvet jacket, breeches, and a feathered hat. His tiny paws clutched at her finger when she held him, and he buried his pink face in the folds of her dress. His eyes were big, beseeching.

Cebus capucinus. White-headed capuchin.

The two keepers ordered to mind Plaisir at all times had scars on their hands and arms from bites and scratches, all the way up to their elbows. No chain was enough to restrain the little rascal. Once free, the monkey always found a way to her study. He opened every drawer in her desk, tore papers, spilled ink, chewed at her quills, peed on her chair. He put his finger up his anus and then smeared excrement on the walls. When she screamed at him, he covered his ears and made a grimace of such relentless misery that she laughed.

On one of his mischievous sprees, Plaisir smashed a jar of her face cream and ate its contents. A few hours later, he crept under a chair in her bedroom and wouldn’t come out. No treats, none of his favorite toys would tempt him. “Leave him,” she ordered the servants. “He’ll come out when he gets hungry.” Only he didn’t. He just shrank and died.

9:10 a.m.

To stand up, many muscles have to be kept taut, many bones lifted. In the meantime, every heartbeat calls for her attention.

The memory of Platon’s hoarse voice interrupts her concentration. “Why are you hurting me, Katinka? You are all I’ve got. Without you, I’m dust.”

The voice of her lover is insistent, pleading. She pictures Platon standing next to her, so crushingly beautiful in his charcoal-colored ensemble, his features pure. Nose, jawline, lips. If she could draw, she would sketch him in black ink. Then smudge the edges to soften him.

Have I hurt you, Platon? How? And when?

This is a problem she could solve. Unravel the puzzling configuration of cause and effect, if only she thought about it long enough. She has always been good with ciphers. Numbers that turn into letters. Words that stand for other words. To solve a puzzle one needs to look for patterns, the rhythm of repetitions.

But why does Platon begin to whistle, and then sing?

Russia reaches farther-higher

Over mountain peaks and seas.

How can she solve a puzzle that shifts its shape, flickers like a firefly, and then disappears into the dark? How can she solve a puzzle when all she can be certain of is the searing pain in his voice?

9:11 a.m.

“Crying all night . . . again . . . poor child . . . this is not the end of the world, Her Majesty told her so many times . . . but the young never listen . . .”

The voices in the antechamber veer off, like nervous horses bent on flight. Sometimes whole phrases come through the walls, sometimes only words.

“It hurts more when you are young.”

“Such a shame.”

“How could he . . .”

She should try to hear more, learn what the servants are talking about. It’s useful to know what is not meant for your ears.

But the headache is not going away. Each pang is a blow, enclosing her in a roaring fog. Voices, groans, a loud drumming sound. Her palms moisten with sweat.

Such headaches have plagued her before. The bursts of blinding light are not new, either. It’s not surprising. She has been working too much, too hard. But what looks done one day disintegrates on the next. No wonder that the weight in her chest gets heavier.

The Polish campaign is over, but the Polish partition treaty is still not finished, her last objections still not resolved. The Prussians want to keep Warsaw, but won’t yield anything of value in return. As always, they want Russia to get their chestnuts out of the fire for them!

Nations are like merchants. They form and break alliances according to the rules of costs and profits. A country that wishes no expansion will wither. Stillness is an illusion. Empires need to grow or face defeat. This is why she has taxed her body beyond its strength. In the service of her empire. Are other monarchs working as hard as she is? Without stopping?

She needs a good long rest.

The Earth hides many secrets.

This is a good thought. Useful and pleasant.

In Siberia, serfs dig out giant bones buried several fathoms underground. “Fossilized ivory, Your Majesty,” scholars tell her. “Brought here by the current of an ancient river.” But ivory does not grow in the shape of bones. Elephants must have once lived where now there is nothing but snow. If one is patient, the strangest transformations are possible.

Remember these words, she orders herself. Write them down as soon as you are back at your desk. Use them when you talk to Alexandrine.

Outside her privy, noises grow and diminish. Feet clatter. Something metallic bangs, then rolls away. The dog’s nails are scratching the wooden floor. Voices she hears are too loud, or sound hollow, as if coming from inside a deep well.

Her servants are jostling among themselves. Queenie is asserting her position. Vishka opposes her, slowly, with measured, relentless cadences. It matters little what they are talking about. Prices of silk, salt, Crimean wines. The likelihood of the Neva freezing soon. Predictions—even those professed by experts—are hardly ever accurate. Conviction is merely a sign of the speaker’s self-assurance.

A telltale sign of arrogance.

9:13 a.m.

The commode has a soft leather seat. When she moves, the leather creaks. Back and forth. Slowly, gently. The swaying of the body soothes. This is how being in a cradle must feel to an infant.

Inside her belly a throb, a mounting pressure of blood. As if her menses have returned. Which cannot be.

The flashes of light are gone now, replaced by elongated floating shapes that drift through her field of vision. Glowing against the ray of pale morning sun that comes through the small window up high. Sometimes blurry, sometimes transparent. Sinking to the bottom when she tries to look at them closer.

Empress of the Night: A Novel of Catherine the Great

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- hardcover: 400 pages

- Publisher: Bantam

- ISBN-10: 0553808133

- ISBN-13: 9780553808131