Daniel

Review

Daniel

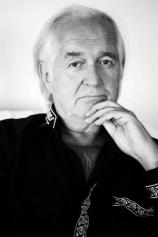

Swedish writer Henning Mankell is best known for his Kurt Wallander police procedurals. But his new book, DANIEL, is a heart-wrenching and moving stand-alone novel set in the late 19th century.

It tells the story of Molo, an African orphan, and a Swede named Hans Bengler, who has been looking for insects in the Kalahari Desert. His plan is to find one that nobody else has discovered and to travel around Sweden displaying his collection. When he reaches an oasis in the sand, he sees a black boy who is being kept in a crate like a wild animal. In a rash moment, he decides to adopt him and “christens” him Daniel. Bengler has no idea nor does he care that within himself the child is still Molo. He tells Daniel to call him Father, but the boy remembers the parents who brought him up. Neither understands the other’s language, which makes communication between them very awkward, especially since part of Bengler’s plan is to display Daniel as an oddity in his show.

They seem to be traveling endlessly as they make their way back to Sweden, and when the two reach Lund, a farmhand stands frozen in his steps upon seeing Daniel. He keeps repeating, “What is this?” “His name is Daniel,” replied Bengler. “He’s a foreigner on a visit to our country.” The farmhand wants to know if Daniel is some kind of animal: “I’ve never seen anything like it,” he said. “I’ve seen dwarfs and giant women and Siamese twins at fairs. But not this.” “He’s here so that we can look at him,” said Bengler. “Human beings are made in different forms. But they are all the same inside.”

Bengler is a strange man who is very inward-thinking. He is solipsistic, which makes life more difficult for Daniel, who lives an active inner life planning to get back to the Kalahari Desert --- the polar opposite of the cold forests of Sweden. Daniel hears the story of Christ walking on water and sees a wooden crucifix hanging in a church. In his head he believes that these (Swedes) are more primitive than he had imagined. Daniel plans to learn to walk on water and make his way back to the desert. He sneaks out at night and goes to the local wharf to practice. Bengler is furious when he discovers that Daniel is leaving their crummy hotel room and wandering the night. Thus he ties him up and keeps part of the rope around his own hand. While it seems that Bengler might be trying to “humanize” Daniel, readers will be on to his game early in their relationship.

When Bengler realizes that he will not be able to make a living showing off his bugs and the coal black boy, he abandons him to a middle-aged couple who doesn’t have any children. Again Daniel is transplanted, abandoned and winds up with strangers who have no idea how to communicate with him or deal with him to make his life easier. This takes him further away from the water, and he plans constantly how he can get back to the sea and learn to walk upon it.

But here he meets Senna, a retarded girl who tells him she’s crazy. They become friends of sorts, and the two outcasts get along to a certain extent. Slowly Daniel learns to speak Swedish and is able to communicate and understand enough to get by. Senna is the first person he thinks he can trust. They want to run away together, but “life happens.”

DANIEL is a jarring book that provokes readers to remember that racist prejudices are not just a 20th- or 21st-century phenomenon. In the book’s epilogue, the narrative jumps forward to 1995, and we are told about a man who is searching for information about Daniel and Bengler. He meets a tribe of nomads and tells them the story of Daniel and his tribulations in Sweden. They cannot help him with any information, but they seem to know the story from beginning to end as if it has been part of their consciousness for 120 years.

In the afterword, Mankell writes: “This is a novel …[and] does not necessarily depict what actually happened.” The twists and turns in this almost mystical story prove the truth of those words.

Reviewed by Barbara Lipkien Gershenbaum on October 3, 2011