Excerpt

Excerpt

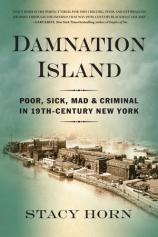

Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad, and Criminal in 19th-Century New York

Workers for the Edison Electric Illuminating Company had spent more than a year ripping up the streets of lower Manhattan. The miles of cable that now lay unseen somewhere beneath their feet were making some people nervous. Two weeks before the new lamps were to be lit for the first time, the New York Times ran a story about horses that had been shocked on one of the blocks within the electrified grid. Absurd, Edison Electric responded. The conductors were buried two feet underneath the street, and encased in an iron pipe a quarter of an inch in diameter. Even if the pipe broke, the current would “scatter through the earth” rendering it utterly harmless. Anything could have spooked those horses.

The first test of electric light distributed via a central power station in New York City would go ahead as planned, on September 4, 1882.

On Monday afternoon at 3 p.m. the switch was thrown. Four-hundred lamps for eighty-five initial customers came to life, powered by six 27-ton, exuberantly named dynamos (today called generators). One of those customers was the New York Times. A grateful reporter wrote about working that night by light as “bright as day . . . without a particle of flicker, and with scarcely any heat to make the head ache.” The new lights also lit up their rooms without the nauseating smell of the gaslights that electricity replaced. That December, a vice president of Edison’s company wrapped his family’s Christmas tree with eighty red, white, and blue light bulbs, and placed it on a revolving pine box. As the tree turned, the tiny lights went off and on, creating a “continuous twinkling of dancing colors” for his lucky children, and neighbors who strolled by for a peek inside. Everything, “all the lights and the fantastic tree itself with its starry fruit,” which “kept going by the slight electric current brought from the main office on a filmy wire,” so delighted a Detroit Post and Tribune reporter who was in New York that he could “hardly imagine anything prettier.”

The city itself became a fantastic display as Edison and his competitors raced to illuminate all the streets. An editor visiting from London described the sight: “The effect of the light in the squares of the Empire City can scarcely be described, so weird and so beautiful is it.” What some had feared, he saw as magical. “Enormous standards, rising far above the trees, are erected in the centre of each square. From these standards the light is thrown down upon the trees in such a way as to give them a fairy-like aspect . . . the shadows they cast on the pavement below appear very like living objects.”

As time went on, more and more outdoor lamps lit up Manhattan, and by 1884 the “bright, white moonlight effect” could be seen for miles around, a glow that illuminated the city every evening, like a brilliant cloud.

That same year, the City of New York sent tens of thousands of people to Blackwell’s Island, a narrow, two-mile-long strip in the East River where they’d built a “Lunatic Asylum,” an “Almshouse for the Poor,” two penal institutions, and over half a dozen hospitals for different classes of inmates. For those who caught an evening glimpse the night before being ferried across, it might have felt like they were being carried away from a radiant future that they would never inhabit. Instead, they were transported into the dank, nauseating, gas- and kerosene-lit past of Blackwell’s Island, where they would be swallowed up—the enchanted, incandescent island of Manhattan in fact lost to many of them forever.

Those sent to the prisons, or even the Lunatic Asylum, could at least entertain a hope of one day getting out, assuming they weren’t committed during a cholera outbreak which could kill them, or housed with a murderous inmate, who might do the same. But a great number of them, especially the unfortunates sent to the Almshouse, were generally too old or their bodies too broken to hope they would ever return to the bright city again. Their prospect for recovery had been judged so unlikely that someone had written Future Doubtful, or worse, Permanently Dependent, on their application for relief. For them, the Almshouse would be their last stop before death, dissection, and a burial in the potter’s field.

Initial planners for Blackwell’s would have been mortified at how wretched and deadly conditions there had become. When the island was bought by the city for $32,500 in 1828 (they would end up paying $20,000 more to settle a lawsuit), their goal was to relieve the crowded conditions at Manhattan’s Bellevue, which in addition to being a hospital was also the location of the city’s Penitentiary, the Lunatic Asylum, an Almshouse for the poor, and the Workhouse, a prison for people convicted of minor crimes. As the city had grown, so had the number of the poor, the lunatic, and the criminal, all of whom had to be treated somewhere when they got sick.

“Why have we not establishments worthy of our city?” an expert they would consult later asked, summing up just what legislators had been thinking at the time. Their idea was to move the sick, mad, and punishable away from the general population and into the more humane, stress-free, and healthful environment of this lush, pastoral island, thick with fruit trees, where they could be classified according to their affliction or crime, installed in their respective institutions, controlled, and finally reformed. The inmates would get all the benefits of modern science and a chance at a future, and except for the employees of the institutions, no one need be troubled about their existence ever again. The island also conveniently had stone quarries that could serve the dual purpose of providing the city with the materials for the buildings, and the prisoners and the poor with a useful occupation: breaking, blasting, and preparing rocks.

Everyone was in high spirits on that promising day when the cornerstone of the first institution was laid. John Stanford, the city’s prison chaplain, thanked God for teaching America “how to season justice with mercy,” and a confident Mayor William Paulding Jr. told the assembled crowd of guests that their state-of-the-art establishment would “prove an honor to our city.” What could be more restorative for the unfortunates of the burgeoning metropolis, it was reasoned, than the peaceful, verdant island in the East River, tucked safely away from vice and crime between two swiftly running channels, surrounded by picturesque sailboats, ferries, and steamers, and the wooded reaches of upper Manhattan and Queens behind them?

Blackwell’s Island was an extension of everything the New World offered, poured into 147 acres. Even the marginalized and maligned would have it better here and nothing less than the latest scientific methods would be employed to give them a chance to turn their lives around. On the Island everyone would be tended to in brand-new institutions with pioneering facilities. Whether they were consigned there for humane punishment, healing or relief, this was America, and here in America we were going to do everything better. The mayor and his fellow dignitaries crossed the river back to Manhattan satisfied that they’d put the largest city of the expanding young country firmly on the path of enlightened reform.

Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad, and Criminal in 19th-Century New York

- Genres: History, Nonfiction

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Algonquin Books

- ISBN-10: 1616209356

- ISBN-13: 9781616209353