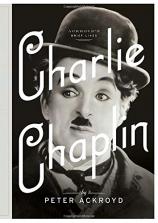

Charlie Chaplin: A Brief Life

Review

Charlie Chaplin: A Brief Life

He was the most famous man in the world, so famous that, as Peter Ackroyd writes in this engaging biography, “Marcel Proust for a time trimmed his moustache in the Chaplin style.” By 1915, Charlie Chaplin had perfected a character that is one of the most enduring and recognizable in the history of cinema: the Little Tramp, with his bowler hat, the too-small jacket fastened by a safety pin, and the “duck waddle” that Chaplin based on the movements of a man who minded horses for the customers of a South London public house in Chaplin’s youth. His fame and appeal were worldwide. Ghanaians would pack theaters and shout, “Charlee!”, the only word they knew in English, when he appeared on screen. Japanese filmgoers called him Professor Alcohol, because they loved his impression of the “funny drunk.”

Chaplin is also one of the most written-about film directors. The bibliography Ackroyd includes in CHARLIE CHAPLIN contains 84 books about the artist, including Chaplin’s MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY, in which, by all accounts, Chaplin glossed over, omitted or distorted salient facts about his life. You’d think that, given the availability of so many fine biographies, there would be no need for another. Whether it’s needed or not, this book is a fine addition to the literature of a man who, as Ackroyd beautifully puts it, “had the inestimable advantage of being an instinctive artist in the preliminary years of a new art.”

"[T]his book is a fine addition to the literature of a man who, as Ackroyd beautifully puts it, 'had the inestimable advantage of being an instinctive artist in the preliminary years of a new art.'"

Charles Chaplin was born in South London in 1889. His mother, Hannah, a music hall performer who went by the stage name Lily Harley, was unfaithful to her husband. Chaplin was never quite sure who his father was, but Charles Chaplin Sr., Hannah’s husband at the time, gave the boy and his older brother, Sydney, his surname, if not his love and attention.

Ackroyd does a nice job of evoking the South London of Chaplin’s childhood. He writes of the hat-making and leather-tanning shops; the smells of vinegar, smoke and dog dung; and the gin palaces and brothels that were as much a part of Chaplin’s boyhood as his parents’ alcoholism and the strict discipline of the “thoroughly Victorian” Hanwell school he and his brother were forced to attend.

Chaplin’s escape from this oppression began when, at age nine, he joined a troupe called The Eight Lancashire Boys. However, his career stalled for years after this stint until, when Chaplin was 14, a theatrical agency cast him as a pageboy in a national tour of Sherlock Holmes. He received good reviews, and soon he was working for Fred Karno, a theater impresario who taught him the secrets of the art of slapstick. Among them, “Keep it wistful… When you knock a man down, kiss him on the head.”

The challenge a biographer faces is to come up with fresh insights into his subject. Most film aficionados know the trajectory of Chaplin’s life and career: many marriages; a womanizing streak; the brilliant films (first with Mack Sennett, then with Essanay Studios, Mutual, First National, and finally with United Artists, which Chaplin founded with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and D.W. Griffith). But Ackroyd meets the challenge. He writes that First National employees could tell Chaplin’s mood each morning by the color of suit he wore. Chaplin didn’t mind if a microphone accidentally appeared in a shot because he believed “that film was there simply to record his performance.” More chillingly, Ackroyd notes that this most sentimental of directors could be violent and misogynistic. Of the short subject Laughing Gas, Ackroyd writes, “[Chaplin] engages a female patient in what another period might describe as sexual assault,” behavior that Chaplin replicated off-screen.

CHARLIE CHAPLIN would have been better if it had been less linear. Ackroyd takes us from one event in Chaplin’s life to the next with relatively little synthesis. The narrative feels rushed at times, as if Ackroyd was trying to cram all the salient details of Chaplin’s life into a short book. And he occasionally makes dubious claims, such as, “All popular comedy, from the commedia dell’arte to the contemporary pantomime, is homoerotic,” although it’s fair to point out that many of Chaplin’s gestures --- his hands on crossed knees, his eyelashes batting at other men --- could be interpreted as an outdated use of supposedly effeminate behavior to get a laugh. Despite these minor lapses, however, this is a well-written biography that will entertain Chaplin’s many fans.

Reviewed by Michael Magras on October 31, 2014

Charlie Chaplin: A Brief Life

- Publication Date: October 28, 2014

- Genres: Biography, Entertainment, Nonfiction, Performing Arts, Television

- Hardcover: 304 pages

- Publisher: Nan A. Talese

- ISBN-10: 0385537379

- ISBN-13: 9780385537377