Excerpt

Excerpt

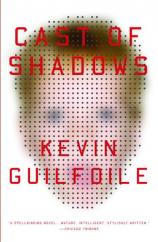

Cast Of Shadows

Davis Moore is a fertility doctor in Chicago specializing in reproductive cloning. When his daughter is raped and murdered by an unknown assailant, he entertains a monstrous thought...

The detective was polite each morning when he called, and Davis feigned patience each morning when the detective, after small talk, confessed to having no leads. Well, not zero leads, exactly: A profile had been made of the attacker. The police believed he was white and fair-skinned. They had some general idea about his size, based on the placement of the bruises and the force exerted on her arm, breaking it in two, but that ruled out only the unusually short and the freakishly tall. They did not think he was obese, according to their reconstruction of the rape itself. He may or may not have been someone Anna Kat knew--probably not, because if she had been expecting someone that night she might have told somebody, but then again, who can say?

The Medical Examiner said the injuries were consistent with rape, but could not comment on whether the District Attorney would include sexual assault along with the murder charge when police apprehended a suspect. When Davis expressed outrage after that information had appeared in the paper, the detective settled him down and assured him that when a beaten, broken, strangled girl has fresh semen inside her, that's a rape in the cops' book no matter what the M.E. says and then he apologized for putting it that way, for being so goddamn insensitive, and then Davis had to reassure the detective. That's all right. He didn't want them to be sensitive. He wanted the police to be as angry and raw as he was. The detective understood that the Moores wanted a resolution. "We know you want closure, Dr. Moore, and so do we," he said. "Some of these cases take time."

Often, the police told the Moores, a friend of the victim will think aloud during questioning, "It's probably nothing, you know, but there's this strange guy who was always hanging around..." This time, none of Anna Kat's friends could offer even a cynical theory. Fingerprints were too plentiful to be useful ("It's the Gap," the detective said. "Everyone in town has had their palms on that countertop") and they were sure the perpetrator had worn gloves anyway, by the thickness of the bruises on her wrists and neck. Daniel Kinney, Anna Kat's off-again boyfriend, was questioned three times. He was appropriately distraught and cooperative, submitting to a blood test and bringing his parents, but never a lawyer.

Blonde hairs were found at the scene and police determined they belonged to the killer by comparing the DNA to his semen. With no suspect sharing those same microscopic markers, however, the evidence was an answer to an unasked question. A proof without hypothesis. Before or during the rape, she had been beaten. During or possibly after the rape, she had been strangled. One arm and both legs were broken. Seven hundred and forty nine dollars were missing from a pair of registers and there might have been some clothes gone from the racks (the embarrassed store manager wasn't sure about that, inventory being something of a mess, but it's possible that a few pocket tees were taken. Extra Large. The police noted this in their profile).

Northwood panicked for a few weeks. The bakery, True Value, Coffee Nook, fruit stand, two ice cream parlors, six restaurants, three hairdressers, and two dozen or so other shops, including the Gap, of course (but not the White Hen), began closing at sundown. More spouses met their partners at the train, their cars in long queues parallel to the tracks each night. The cops put in for overtime, and the town borrowed officers from Glencoe. If you were under 18, you were home before curfew. The Chicago and Milwaukee TV stations made camp for awhile on Main Street (news producers determined that Oak Street, where the Gap shared the block with a carpet store, parking lot, and funeral home, didn't provide enough "visual interest" and chose to shoot stand-ups around the corner where there was more pedestrian traffic and overall "quaintness"), but there turns out to be a limit to the number of nights you can report that there is, as yet, nothing to report, and TV crews disappeared as a group the day a Northwestern basketball player collapsed and died of an aneurysm during practice.

The old routine returned in time. By spring, Anna Kat might not have been forgotten--what with the softball team wearing the "AK" patch, the special appointment of Debbie Fuller to fill the vacancy of Student Council Secretary, and the three-page, full-color yearbook dedication all keeping her top of mind around campus--but Northwood became unafraid again. A horrible alien had killed on its streets; Northwood had been shattered, and the people made repairs. The town grieved and, like the alien, moved on.

***

Eighteen months after the murder, the detective told Davis (still calling twice a week) that he could pick up Anna Kat's things. This doesn't mean were giving up, he said. We have the evidence photographed, the DNA scanned. Phone ahead and we'll have them ready. Like a pizza, Davis thought.

"I don't want to see them," Jackie said. You don't have to, he told her.

"Will you burn the clothes?" He promised he would.

"Will they ever find him, Dave?" He shook his head, shrugged, and shook his head again.

He imagined a big room with rows of shelves holding boxes of carpet fibers and photos and handwriting samples and taped confessions, evidence enough to convict half the North Shore of something or other. He thought there would be a window and, behind it, a chunky and gray flatfoot who would spin a clipboard in front of him and bark, "Shine heah. By numbah fouwa." Instead, he sat at the detective's desk and the parcel was brought to him with condolences, wrapped in brown paper and tied with fraying twine.

He took it to his office at the clinic, closed the door, and cut the string with a pair of long-handled stainless-steel surgical scissors. The brown postal paper flattened into a square in the center of his desk and he put his hands on top of the pile of clothes, folded but unwashed. He picked up her blouse and examined the dried stains, both blood and the other kind. Her jeans had been knifed and torn from her body, ripped from the zipper through the crotch and halfway down the seams. Her panties were torn. Watch, ring, earrings, gold chain (broken), anklet. There were shoes, black and low-heeled, which they must have found near the body. With a shudder, Davis remembered those bare, mannequin feet.

There was something else, too.

Inside one of the shoes: a small plastic vial, rubber-stoppered and sealed with tape. A narrow sticker ran down the side with Anna Kat's name and a bar code and the letters "UNSUB" written in blue marker, along with numbers and notations Davis couldn't decipher. UNSUB, he knew, stood for "unidentified subject" which was the closest thing he had to a name for his enemy.

He recognized the contents, however, even in such a small quantity.

It was the milky-white fuel of his practice, swabbed and suctioned from inside his daughter's body. A portion had been tested, no doubt--DNA mapped--and the excess stored here with the rest of the meager evidence. Surely they didn't intend this to be mixed up in Anna Kat's possessions. This stuff, for certain, did not belong to her.

He planned for a moment on returning to the police station and erupting at the detective. "This is why you haven't found him! He's still out there while you fumble around your desk, wrapping up tubes of rapist left-behind and handing them out to the fathers of dead girls like Secret Santa presents!"

The stuff in this tube, ordinarily in his workday so benign, had been a bludgeon used to attack his daughter, and his stomach could not have been more knotted if Davis had discovered a knife used to slit her throat. He had often thought of sperm and eggs--so carefully carted about the clinic, stored and cooled in antiseptic canisters--as being like plutonium: with power to be finessed and harnessed. The stuff in this tube, though, was weapons grade, and the monster that had wielded it remained smug and carefree.

There was more. A plastic bag with several short, blonde hairs torn out by the roots. These were also labeled UNSUB, presumably by a lab technician who had matched the DNA from the follicles to genetic markers in the semen. There were enough hairs to give Davis hope that AK had at least inflicted some pain, that she had ripped these from his scrotum with a violent yank of her fist.

Rubbing the baggie between his fingers, Davis conjured a diabolical thought. And once the thought had been invented, once his contemplation had made such an awful thing possible, he understood his choices were not between acting and doing nothing, but acting and intervening. By even imagining it, Davis had set the process in motion. Toppled the first domino.

He opened a heavy drawer in his credenza and tucked the vial and the plastic bag into the narrow space between the letter-sized hanging folders and the back wall of the cabinet.

In his head, the dominoes fell away from him, out of reach, collapsing into divergent branches with an accelerated tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-tap.

***

Justin Finn, nine pounds, six ounces, was born on March 2 of the following year. Davis monitored the pregnancy with special care and everything had gone almost as described in Martha's worn copy of What to Expect When You're Expecting. There was a scary moment, in month six, when the child was thought to be having seizures, but they never recurred. It was the only time between fertilization and birth that Davis thought he might be exposed. Baby Justin showed no evidence of brain damage or epilepsy, and after the Finns took their happy family home, they sent Davis a box of cigars and a bottle of 25-year-old Macallan.

The house on Stone fell into predictable measures of hostility and calm. Davis and Jackie were frequently cruel to one another, but never violent. They were often kind, but never loving. An appointment was made with a counselor but the day came and went and they both pretended it had slipped their minds.

"I'll reschedule it," said Jackie.

"I'll do it," said Davis, generously relieving her of responsibility when the phone call was never made.

In the third month of the Finn pregnancy, Jackie had left to spend time with her sister in Seattle. "Just for a visit,"she said. Davis wondered if it were possible their marriage could end this way, without a declaration, but with Joan on a holiday from which she never returned. He didn't always send the things she asked for--clothes and shoes, mostly--and she hardly ever asked for them twice. Jackie continued to fill the prescriptions he sent each month along with a generous check.

In Jackie's absence, Davis avoided social, or even casual, conversation with Joan Burton. It had been fine for him to admire Dr. Burton, even to fantasize about her when he could be certain nothing would happen. Throughout his marriage, especially when Anna Kat was alive, Davis knew he was no more likely to enter into an affair than he was apt to find himself training for a moon mission, or playing fiddle in a bluegrass band. He wasn't a cheater, therefore it was not possible that he could cheat. With Jackie away and their marriage undergoing an unstated dissolution, he could no longer say a relationship with Joan was impossible. He feared the moment, perhaps during a weekday lunch at Rossini's, when their pupils might fix and the dominoes in his head would start toppling again: tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-tap.

Jackie returned just before Christmas as if that had been her intention all along. She and Davis fell back into their marriage of few words. Davis restarted the small talk with Joan, even buying her a weekday lunch at Rossini's.

Anna Kat had been dead for three years.