Excerpt

Excerpt

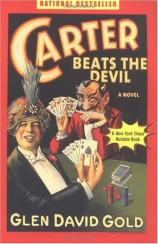

Carter Beats the Devil

Read a Review![]() The

The

most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the

fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true

science. Whoever does not know it and can no longer wonder, no

longer marvel, is as good as dead, and his eyes are dimmed.

--Albert EinsteinOn

Friday, August third, 1923, the morning after President

Harding’s death, reporters followed the widow, the Vice

President, and Charles Carter, the magician. At first, Carter made

the pronouncements he thought necessary: "A fine man, to be sorely

missed," and "it throws the country into a great crisis from which

we shall all pull through together, showing the strong stuff of

which we Americans are made." When pressed, he confirmed some

details of his performance the night before, which had been the

President’s last public appearance, but as per his proviso

that details of his third act never be revealed, he made no comment

on the show’s bizarre finale.Because the coroner’s office could not explain exactly

how the President had died, and rumors were already starting, the

men from Hearst wanted quite desperately to confirm what happened

in the finale, when Carter beat the Devil.That

afternoon, a reporter disguised himself as a delivery man and

interrupted Carter’s close-up practice; the magician’s

more sardonic tendencies, unfortunately, came out. "At the time the

President met his maker, I was in a straitjacket, upside-down over

a steaming pit of carbolic acid. In response to your as-yet-unasked

query, yes, I do have an alibi."He

was almost immediately to regret his impatience. The next day over

breakfast he saw the headline in the Examiner: "Carter the Great

Denies Role in Harding Death." Below was an article including, for

the first time, an eyewitness first-person narrative from an

anonymous audience member who all too helpfully described the

entire show, including the third act. He could not confirm whether,

in fact, President Harding had survived until the final curtain.

After a breathless account of what Carter had done to the

President, the editors reflected on Lincoln’s assassination

at Ford’s Theater fifty-eight years beforehand, then made a

pallid call for restraint, for letting the wheels of justice

prevail.Carter, a sober man, knew he might be lynched. At once, he

ordered his servants to pack his steamer trunks for a six

months’ voyage. He booked a train from San Francisco to Los

Angeles, then transit on the Hercules, an ocean liner bound from

Los Angeles to Athens. He instructed his press agent to tell all

callers that he was seeking inspiration from the priestess at

Delphi, and would return at Christmastime.Carter was chauffeured from his Pacific Heights mansion to the

train station downtown, where a crowd of photographers jostled each

other to shoot pictures of him. As he boarded the Los Angeles-bound

train, he made no comment other than to turn up the collar of his

fur-lined coat, which he hardly needed in the August

heat.By

the time the train arrived in Los Angeles, Secret Service agents

were posted at all exits. They had just received authorization to

detain Mr. Charles Carter. But this posed an unexpected challenge.

Though they saw several pieces of Carter’s luggage leaving

the train, Carter himself was nowhere to be found. His servants

were halted, and his bags opened and searched right on the

platform, but law enforcement concluded that Carter had slipped

away.Passengers boarding the were given the professional bug-eye by

agents who’d received copies, by teletype transmission, of

Carter’s publicity photograph. Since these images featured

him in a silk floral turban, with devils drawn onto his shoulders,

and his face thrown into moodily orchestrated shadows, they also

received careful descriptions of what Charles Carter actually

looked like: thirty-five years old, black hair, blue eyes, Roman

nose, pale, almost delicate skin, and a slender build that allowed,

it was said, exceptionally agile movement. Informants could not say

for certain whether Carter was the type of magician who was a

master of disguise; San Francisco’s law enforcement was of

the opinion that he was not. He was, they thought, the type who

specialized in dematerialization. This did not set the

agents’ minds at ease, and when every passenger had been

examined, they were no closer to catching their man than they had

been on the train. He had not stowed away with the crew, nor with

the luggage -- both had been examined minutely.Finally, the agents concluded he had been scared off by the

attention. The Hercules was allowed to sail, and as soon as it

cleared the breakwater, the harbormaster saw through his binoculars

the unmistakable form of Charles Carter, in bowler hat and

chinchilla coat, sipping champagne and waving adieu from the aft

deck.Authorities on board and at every port along the way were

alerted to Carter’s presence, but even the most optimistic

federal agent suspected the magician would never be

found.This

was hardly the Secret Service’s first disaster, only the most

recent. Morale among all government bodies had plummeted during the

twenty-nine months of the Harding administration. As one scandal

followed another, it became apparent that in stark contrast to

President Wilson, Harding tolerated corruption. In short, the whole

government to a man realized that only bastards got

ahead.For

Agent Jack Griffin, this philosophy was no adjustment

whatsoever.On

the evening of Carter’s performance for President Harding,

Griffin had been told to report to the Curran Theatre. Though his

duties -- "analyze local grounds for all malicious forces" --

sounded important, he knew he was superfluous. The Curran was

undoubtedly secure: magicians took extraordinary precautions

against competitors’ stealing their secrets. Furthermore, a

follow-up detail would double-check the entrances, exits, and the

President’s seats. Nonetheless, Griffin would make a thorough

report; after a twenty-year cycle of probations and remedial

duties, he remained determined to show he couldn’t be broken

by lame assignments.The

Curran, a monstrous and drafty theatre, had just been refurbished

to accommodate pageants, top-flight entertainments, and prestigious

motion pictures. The orchestra pit had been expanded to seat one

hundred musicians and a projection room had been added in the back

balcony. The old Victorian motifs -- a ceiling mural of

pre-Raphaelite seraphim, for instance -- had been co-joined with

Egyptian themes. The walls now rippled with hieroglyphs and the

apron of the stage was flanked by huge plaster sphinxes whose eyes

glowed in the dark.Since Harding was coming to San Francisco as a stop on his

Voyage of Understanding, an effort to refocus his tired

administration, he would likely come onstage during the evening,

perhaps even volunteer in one of Carter’s illusions. Thus

Griffin was to determine which act might be most dignified for the

President.He

came to the Curran in the late afternoon, while workmen were

testing filaments and maneuvering black draperies into their

places. He interviewed Carter’s chief effects builder, a

stooped old man named Ledocq, a Belgian who wore both a belt and

suspenders, and who frequently scratched just above his ear,

threatening to dislodge his yarmulke. Griffin wrote in his notes

"Jew."Ledocq wouldn’t let Griffin examine any of the illusions

onstage, but he described the effects in detail: the show opened

with "Metempsychosis," in which a suit of armor came to life and

chased one of Carter’s hapless assistants around the stage.

(As this seemed like tomfoolery to him, Griffin noted that Harding

should probably not participate in this.) "The Enchanted Cottage"

was a series of quick changes, dematerializations, and

reappearances culminating in "A Night in Old China," an enthralling

display of fire-juggling, fire-eating, and fireworks. (Griffin

wrote "sounds dangerous -- doubtful" in his notes.) Next, Carter

placed a subject, usually an attractive young woman whom he

selected from the audience, into an ordinary wooden chair, which

rose above the stage without apparent assistance. He asked the

subject humorous questions, keeping the audience enthralled while

he pulled out a pistol, loaded it, and carefully shot the woman

point-blank -- the chair fell to the ground, but the subject

disappeared into the ether. ("Absolutely not!" Griffin wrote,

underlining this notation.)After the intermission was a levitation, psychical mind

reading, and prediction routine with Carter’s associate,

Madame Zorah. ("Possible," Griffin wrote, "but won’t it hurt

Px Harding’s credibility?") He asked, "What else is

there?"Ledocq scratched above his ear and squinted at Griffin. "Well,

there’s not a lot left then. There’s the Vanishing

Elephant trick.""Would the President be in danger from the

elephant?""Mmmm. No." Ledocq smiled. "But I can’t imagine a

Republican being happy making an elephant disappear."Griffin crossed out the Vanishing Elephant. "Isn’t there

a third act?""There is. There is. It’s hard to explain.""To

tell you the truth," Griffin sighed, "I don’t really care

about every detail of every trick. Should the President be

involved?"Ledocq laughed, a dry cackle. "Believe me, you don’t want

your boss anywhere near the stage when Carter beats the

Devil."An

hour later, at the Palace Hotel, Griffin produced his full report,

typing it on his Remington portable and inking in the places where

the keys hadn’t come down hard enough to make duplicates. He

went to the Mint to turn it in, and returned to his room. Twice, he

picked up the phone and asked the operator if there were any calls

for him. There weren’t.Just

before the performance that night, the Bureau Chief met in the

lobby with eighteen agents, including Griffin, to pass out programs

and set up a duty roster for the evening. The Chief announced that

the President would indeed go on stage -- as a volunteer in the

third act. When Griffin objected, he was told -- lectured,

actually, for the senior agents all knew about Griffin -- that

there would be no arguments. The President and Carter had met and

concluded that the most effective use of the President’s time

would be in a trick called -- Griffin mouthed the words as they

were announced -- "Carter Beats the Devil."Griffin, still objecting, was dismissed, and was sent to stand

at the back of the theatre, where he cursed under his breath until

the lights dimmed, when he began to make small, coarse gestures

toward the Bureau Chief and the other Kentucky insiders, who sat in

the eight-dollar seats.The

curtains opened to a spectacularly cluttered set meant to represent

Carter the Great’s study. A lackey bemoaned the

audience’s presence. "Eight o’clock already, the show

is starting, and the master’s room isn’t ready yet.

He’ll have my hide for sure."The

lackey dusted everywhere, with huge clouds choking him when he blew

across the top of an ancient book. Most of the audience laughed,

but not Griffin. He felt a lot of sympathy for the poor guy

onstage. In his haste to clean everything, the lackey knocked over

a suit of armor, which fell to the stage in a dozen pieces,

empty.When

he put it back together again, and returned to cleaning, the suit

of armor snuck up on him and kicked his backside. The audience

roared. Griffin looked at them sourly, thinking, Sophisticates.

What kind of a guy used all his smoke and mirrors to make fun of a

poor egg just doing his job?A

sting of violins, then Elgar’s "Pomp and

Circumstance,"Charles Carter

appeared in his white tie, tails, and trademark damask turban, to

tremendous applause. The suit of armor froze. Carter lectured

his servant about the shabby way his study looked, and asked why

the suit of armor was standing in the middle of the floor. Trying

to explain that the armor had just attacked him, the lackey gave it

a shove. It toppled in pieces, empty, to the stage. No amount of

pleading could convince Carter that his servant was anything but

unreliable.Griffin whispered, "Brother, I believe you."Two

hours later, the curtain went up on the third act. The Examiner of

the next morning would say that "the enthralled audience had

already watched in amazement as a dozen illusions, each more

magnificent than the last, unfolded before their very eyes. The

President himself was heard to say, ‘the show could finish

now and still be a thrilling spectacle.’"Here

the initial newspaper account ended, following Carter’s

request -- printed on the programs and on broadsides posted at the

theatre entrance -- that the third act remain a secret.The

act began on a barren stage. Carter entered and announced that as

he had proven himself to be the greatest sorcerer the world had

ever known, there was no reason to continue his performance, and he

was prepared to send the crowd home unless a greater wizard than he

should appear. Then there was a flash of lightning, a plume of dark

smoke, and the infernal reek of pure brimstone: rotten eggs and

gunpowder. The Devil himself had arrived on stage.The

Devil, in black tights, red cape, close-fitting mask, and a cowl

capped with two sharp horns, issued a challenge to Carter: each of

them would perform illusions, and only the greater sorcerer would

leave the stage alive. As soon as Carter agreed, the Devil produced

a newspaper, and pulled a rabbit from it. Carter responded by

hurling into a floating water basin four eggs, which, the moment

they hit the water, became ducklings. The Devil caused a woman to

levitate; Carter made her disappear. The Devil caused her to

reappear as an old hag. With a great magnesium flash, Carter had

her consumed by flames.Then

the pair began doing tricks independently of each other, at

opposite ends of the stage. While the Devil ushered forth a

floating tambourine, a trumpet, and a violin, which played a

disembodied but creditable rendition of Night on Bald Mountain,

Carter cast a rod and reel into the audience, catching live bass

from midair. The Devil did him one better, sawing a woman in half

and separating her without the casket in place. Carter made hand

shadows of animals on the wall that came to life and galloped

across the stage.The

Devil drew a pistol, loaded it, and fired it at Carter, who

deflected the bullet with a silver tea tray. Carter drew his own

pistol, and fired at the Devil, who caught the projectile in his

teeth.They

brought out two white-bearded, turbaned "Hindu yoga men," each of

whom had a hole drilled through his stomach so that a stage light

could shine through. The Devil thrust his fist into and all the way

through one man, making a fist behind him. Carter bade the other

drink a glass of water, and he caught in a wine goblet the flow

that came from his stomach, as if from a spigot.Then

cannons rolled onto stage, and Carter and the Devil urged their

Hindus into the cannons, each of them aimed skyward so that the

projectiles’ paths would intersect. Then BANG went the

cannons, and out flew the yoga men -- when they collided over the

audience’s head, a burst of lilies rained upon the cheering

crowd.Carter cried that this was enough, that the contest had to be

settled as if between gentlemen. He proposed a game of poker, high

hand declared the winner. When the Devil assented, Carter broke

from the program to approach the footlights. He asked if there were

a volunteer, a special volunteer who could be an impartial and

upright arbiter of this contest. A spotlight found President

Harding, who, with a good-natured wave, acknowledged the

audience’s demand for him to be the judge.Griffin’s eyes were pinwheeling like he’d been

through an artillery barrage. With each volcanic burst of mayhem,

he’d assured himself it was just an optical illusion, that

the President wouldn’t actually be exposed to harm. But

there’d been fire, guns, knives, and, he could barely

consider it, cannons. Harding walked down the aisle, shaking hands

along the way, and flashing his shy but winning smile.Onstage, it was obvious what a big man Harding was, standing

several inches taller, and wider, than Carter. He looked genuinely

pleased to be of service.Carter, Harding, and the Devil retired to the poker table,

where a deck of oversized cards awaited them. Harding gamely tried

to shuffle the huge cards -- the deck was the size of a newspaper

-- until one of Carter’s assistants took over the duty. As

the game progressed, the Devil cheated outrageously: for instance,

a giant mirror floated over Carter’s left shoulder until

Harding pointed it out, whereupon it vanished.Carter had been presenting his evening of magic at the Curran

for two weeks. Each night had ended the same way: he would present

a seemingly unbeatable hand, over which the Devil would then, by

cheating, triumph. Carter would stand, knocking over his chair,

saying the game between gentlemen was over, and the Devil was no

gentleman, sir, and he would wave a scimitar at the Devil. The

Devil would ride an uncoiling rope like an elevator cable up to the

rafters, out of the audience’s sight. A moment later, Carter,

scimitar clenched between his teeth, would conjure his own rope and

follow. And then, with a chorus of offstage shrieks and moans,

Carter would quite vividly, and bloodily, show the audience what it

meant to truly beat the Devil.Carter’s programs advertised the presence of a nurse

should anyone in the audience faint while he took his

revenge.This

night, as a courtesy, Carter offered that President Harding play a

third hand in their contest. Just barely getting hold of his giant

cards, the President joined the game. When it came time to present

their hands, Carter had four aces and a ten. The Devil had four

kings and a nine. The audience cheered: Carter had beaten the

Devil."Mister President," Carter cried, "pray tell, show us your

hand!"A

rather sheepish Harding turned his cards toward the crowd: A royal

flush! Further applause from the audience until Carter hushed

them."Sir, may I ask how you have a royal flush when all four kings

and all four aces have already been spoken for?" Before Harding

could reply, Carter continued: "This game between gentlemen is

over, and you, sir, are no gentleman!"Carter and the Devil each drew scimitars, and brought them

crashing down on the card table, which collapsed. Harding fell back

in his chair, and, uprighting himself, dashed to a rope that was

uncoiling toward the rafters. Harding rose with it. Carter and the

Devil, on their own ropes, followed.In

the back of the theatre, Griffin frantically looked for fellow

agents to confirm what he thought he’d seen. During the past

two weeks of the trip, President Harding had been stooped as if

carrying a ferryload of baggage. In Portland, he’d canceled

his speeches and stayed in bed. The sudden acrobatics -- where had

a fifty-seven-year-old man found the energy?The

whole audience was just as unsure -- the lighting was brilliant in

some places, poor in others, causing figures to blur and focus

within the same second. It forced the mind to stall as it processed

what the eye could have seen. This was a crucial element of what

was to come. For though the visual details fringed upon the

impressionistic, the acoustics were ruthlessly exact: as the

audience clambered for more, there came the sound of scimitars

being put to use.Then, with a thump, the first limb fell to the

stage.The

crowd’s cheers faded to murmurs, which took a moment to fade

away. An unholy silence filled the Curran. Had that been something

covered in black wool? Bent at the -- the knee? Had that been the

hard slap of black rubber heel? A woman’s voice finally broke

the stillness. "His leg!" she shrieked. "The President’s

leg!"The

one leg was followed by the other, then an arm, part of the

body’s trunk, part of the torso; soon the stage was raining

body parts hitting the boards in wet clumps. Griffin unholstered

his Colt and took careful steps forward, telling himself this was

just a magic trick, and not the joke of a madman: to invite the

President onstage, and kill him in front of his wife, the Service,

newspaper reporters, and an audience of one thousand paying

spectators.Chaos took the audience; some were standing and calling out to

their neighbors, others were comforting women about to faint. Just

then, the voice of Carter came from somewhere over the stage.

"Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you the head of state." And then,

falling from a great height, a vision of grey, matted hair, and a

blur of jowls atop a jagged gash, President Harding’s head

tumbled down to the stage apron, striking it with a muted

smack.Screams filled the air. Some brave audience members rushed past

Griffin, toward the stage, but everyone halted in their tracks when

a deep, echoing roar filled the theatre, and a lion catapulted from

the wings onto the apron, where he gorged himself on the

corpse’s remains."He

is all right! I know he must be all right," an hysterical Mrs.

Harding wailed above the din.Suddenly, a single shot rang out. The echo reported across the

theatre. Carter strode from the wings to the midpoint of the stage,

a pith helmet drawn down over his turban. He carried a rifle. The

lion now lay on its side, limbs twitching."Ladies and Gentlemen, if I may have your indulgence for one

last moment." Carter spoke with gravitas, utter restraint, as if he

were the only calm man in the house. Using a handheld electric saw,

he carved up the lion’s belly, and pried it open, and out

stepped President Harding, who positively radiated good health.

Griffin sat down in the aisle, gripping his chest and shaking his

head.As

the crowd gradually realized that they had witnessed an illusion,

the applause grew in intensity to a solid wave of admiration for

Carter’s wizardry, and especially Harding’s good

sportsmanship. It ended in a standing ovation. In the midst of it,

Harding stepped to the footlights and called out to his wife,

"I’m fit, Duchess, I’m fit and ready to go

fishing!"Two

hours later, he was dead.Four

days later, Monday, August sixth, Harding’s remains were on

their way to their final resting place in Marion, Ohio. At the same

time, the Hercules, still under surveillance for signs of Charles

Carter, was in a storm south of the tropic of Cancer. At noon on

that day, Jack Griffin and a superior, Colonel Edmund Starling,

ferried from San Francisco to Oakland. They took a cab to Hilgirt

Circle, at the top of Lake Merritt, where some of the wealthier

families had relocated after the great earthquake. One Hilgirt

Circle was a salmon-colored Mediterranean villa that rambled up the

steep slope of China Hill. There were seven stories, each recessed

above the last, like steps. Whereas its neighbors were hooded Arts

and Crafts fortresses, One Hilgirt Circle was a rococo circus of

archways, terra-cotta putti, gargoyles, and trellises strung with

passion vines. Its builder couldn’t be accused of

restraint.Griffin looked at the one hundred stairs leading to the villa

entrance with dismay, then hitched his trousers over his paunch and

struggled up until short of breath. He had recently started a

program of exercise, but this was a bit much. Starling, thirteen

years younger, went at a brisk trot.Starling was handsome and gracious, a golden boy, one of the

Kentucky insiders, quickly promoted and used to having his opinions

acknowledged. He arose each morning at five to read a chapter of

the Bible, exercise with Bureau Chief Foster, and eat a tidy

breakfast before attacking that day’s work. When enthusiastic

about life (all too often, Griffin thought,) he whistled the tunes

of Stephen Foster. The hardest part for Griffin to bear was

Starling’s relentless, honest humility. Griffin hated himself

for hating him.Reaching the top landing of Hilgirt Circle, the agents had a

magnificent view of the lake, downtown Oakland, and, behind a milky

veil of fog, the San Francisco skyline, which Griffin pretended to

appreciate while he rested.Starling whistled. "Oh, for my rifle at this

instant.""You

think we’re gonna need it?""No,

Mr. Griffin. The mallards on the lake. And I think I see some

canvasbacks, though that would be peculiar, this time of

year."Griffin nodded, dying to look knowledgeable, or intelligent, or

something besides useless around the Colonel. He’d had a

rough few days (guilt, depression, a fistfight, a vow to redeem

himself) and had spent hours researching Charles Carter’s

shadowy past. He had reported his suspicions -- he had many

suspicions -- to Starling, who had said nothing except, "Good

work," which could have meant anything.Out

came Starling’s watch. "If I’m not mistaken, at this

very moment, the Hercules is approaching the Panama Canal, in heavy

seas. This should be most interesting."Then

Griffin knocked at the door of One Hilgirt Circle. It was answered,

almost instantly, by Charles Carter.Carter was still in his stocking feet and wore black trousers

and a shirt to which no collar was yet attached. He looked amused

to see them. Glancing back into his foyer, he then stepped out into

the day, pulling the door closed behind him.Griffin said, "Good morning. Charles Carter?""Yes?""Agents Griffin and Starling of the Secret Service." Griffin

handed Carter his badge. Carter held it in his left hand. Griffin

pointed at Carter’s right hand, which was still extended

backward, keeping the door shut. "Are you concealing anyone or

anything inside?""I’m just trying to keep the cat from getting

out.""Okay. We’d like to ask you some questions about events

of August second.""Certainly.""May

we come in?"Carter frowned. "I don’t think that’s such a good

idea."Griffin looked toward Starling, who gave a nod; obviously, they

had caught the magician up to no good. Griffin continued, "Mr.

Carter, please step aside."Carter ushered the agents past him.Carter’s foyer led to a three-bedroom pied-á-terre

with fireplaces in the parlor and dining room. Since he had

collected curios and Orientalia from every corner of the globe

during his five world tours, it was a room where -- save for one

pressing detail -- the eye hardly knew what to consider first.

There were aboriginal sculptures, magic rain sticks from Sumatra,

geodes on dusty silver stands, and more of the same, but, most

important, Griffin put his hand on the butt of his pistol, for he

saw, sitting on a large Persian rug that covered most of the front

room, an enormous African lion. The lion’s shoulders were

dropping to the floor, ready to pounce. Griffin touched

Starling’s shoulder, and Starling, too, stared at it without

saying a word. Griffin could see its stomach flutter as it

breathed, its tail thumping against the carpet."I

said I didn’t want to let the cat out," Carter

said.Griffin swallowed. "Does that thing bite?""Well," Carter said thoughtfully, "if he does, go limp.

It’s less fun for him that way, and he’ll drop you

sooner or later.""Mr.

Carter," Starling said in his slow Kentucky drawl, "I would

appreciate you locking your pet in a side room for just a few

minutes.""Certainly. Baby, come." Carter whistled between his teeth,

clicked his tongue, and Baby reluctantly looked away from the

agents and followed his master out of the room."Jesus wept," Griffin sighed. He straightened his tie. "Why

does everything have to be so difficult?""There are other occupations, Mr. Griffin."A

moment later, Carter returned, a silk robe around his shoulders.

"May I offer you something to drink?"Starling asked, "Are you going to make it yourself?"Carter’s pale blue eyes flickered, and then, tightening

the cinch around his robe, he bowed. "Yes, Mr. Starling, I’ve

had to squeeze my own oranges for the last few days."Griffin looked back and forth between them with

confusion.Carter continued, "Bishop has always wanted to see Greece. He

sketches, you know. Landmarks and such."Griffin tried to catch Starling’s eye. Bishop? Bishop

who? Once again, Griffin had been passed by.Starling looked for a good spot to sit on a seven-foot leather

couch that was occupied by open volumes of the 1911

Encyclopædia Brittanica. "Mr. Griffin, please make a note:

it’s Alexander Bishop, Carter’s servant, who’s on

the boat." Then, to Carter, "The chinchilla coat was a nice

touch.""He’s always liked it. I am quite serious, would you like

refreshments?""No,

thank you, sir.""But

you, Mr. Griffin, I’m sure you’re game for a muffin or

two." Carter gestured grandly toward the kitchen as if eggs, bacon,

and a raft of toast might dance out on his command. Griffin glared

at him.Starling, looking as comfortable as if he’d been sitting

on fine leather couches for years, glanced at his notepad. "Mr.

Carter, did you speak to the late President alone on the night of

his death?""I

did."Starling asked, "What did you talk about?""Before the performance, we met backstage with the Secret

Service in attendance, and then alone for, what, five minutes

perhaps. I described the various illusions. He wanted to be in the

final act. That was all.""How

was his demeanor?""He

seemed depressed at first.""Did

you ask what was wrong?""In

my years on tour I’ve learned that with the powerful,

it’s wise not to ask such questions.""Was

there anything at all unusual about your conversation?""Only that . . . I’m unsure how to describe it, but his

mood was weary. Yet, when I told him his duties onstage would

involve being torn to pieces and fed to wild animals, he brightened

considerably." Carter shook his head. "That defies reason,

don’t you think?"Starling cleared his throat. "Actually, sir, the President had

been under some stress.""For

a stocky man, he seemed fragile."Starling looked past Carter, to an ukiyo-e woodcut of a Kabuki

player. "Did he happen to mention a woman named Nan

Britton?""He

did not.""A

woman named Carrie Phillips?""He

did not.""Did

he mention anyone else?"Carter looked to the ceiling. "He mentioned my elephant,

approvingly, his dogs, also approvingly, my lion, with some lesser

approval, and though we covered the animal kingdom, I believe that

no one human was mentioned." Carter smiled like a child finishing a

piano recital.Griffin snarled, "Look, Carter, this might be a game to you,

but the President’s death is a matter of national

security.""How

did the President die, exactly?"A

glance between the agents, then Starling spoke. "The cause is

undetermined. Three physicians say brain apoplexy, but no autopsy

was performed."Carter asked, "Why not?"Griffin said, "We’re asking the questions here. It might

have something to do with an exhausted man being forced to do

acrobatics up and down a rope all night long."Carter’s face cleared. "Mr. Griffin, this isn’t a

game to me. I’m able to make a living because I don’t

explain how my effects are performed. But if it helps you: from the

moment the President left the card table, his stunts were performed

by one of my men in disguise. The President hid until after I gave

Baby the signal to play dead. There was no exertion on the

President’s part, and I had nothing to do with his death, I

assure you.""Then why’d you run away, Carter?" asked

Griffin."But, as you know, I didn’t. The feint with the Hercules

was to keep the general public from stringing me up. I thought the

Secret Service would find me. And so you have," he concluded

warmly, like they’d made him proud. "Is there more to this

interrogation?""We’ll tell you when it’s over, pal." Griffin

squinted menacingly at Carter, but saw that Starling was already

folding up his notebook. "Okay," Griffin said, deflating,

"it’s over." He pointed at Carter. "Keep yourself available.

We might have more questions."Carter nodded, as if admitting that into every life a little

rain must fall, which made Griffin want to pop him one.Carter showed the two agents to the door. Griffin began to take

the stairs back down. When he got to the first landing, he heard,

behind him, the Colonel asking if he wouldn’t mind waiting.

Griffin paused. He looked back up fifty or so feet of staircase,

where his superior and the suspect stood and watched him in turn.

He patted his hand against the railing, feeling the vibrations

pinging back and forth, and then, resigning himself to a life out

of earshot, he looked at the view of the lake.At

first, Starling said nothing to Carter. He simply let a few moments

play out in silence. "I wish I knew more about gardens."There were flowers in tiered planters on either side of the

stairs, and trellises of jasmine and honeysuckle. Carter indicated

a few stalks that were growing almost as high as his fingertips.

"This is Thai basil, and that was supposed to be cilantro, but

it’s turned to coriander. Whenever I’m overseas, I pick

up a few herbs. It makes my cook happy.""The

photograph in your drawing room, is that your wife?""She

was my wife. I’m a widower." He said this flatly."I’m sorry." Starling massaged a mint leaf and brought

his fingertips to his nose, closing his eyes.Carter spoke. "Was the President in trouble?""That depends," Starling said, opening his eyes again. "Is

there anything else I should know?"Carter shrugged. "I had but five minutes with the President."

He watched a pelican fly in a lazy circle by the lake. "Being a

magician is an odd thing. I’ve met presidents, kings, prime

ministers, and a few despots. Most of them want to know how I do my

tricks, or to show me a card trick they learned, as a child, and I

have to smile and say, ‘Oh, how nice.’ Still,

it’s not a bad profession if you can get away from all the

bickering among your peers about who created what

illusion."Starling had very small eyes. When they fixed on something, a

person, for instance, it was like positioning two steel ball

bearings. "I see. You put on a thrilling show yourself,

sir.""Thank you.""Now, I’m just an admirer here, and I hope this question

isn’t rude, but have I seen some of those tricks

before?""Those effects? Not the way I do them, no.""So

you are the creator of all of those tricks."Carter found something interesting to look at, over Colonel

Starling’s shoulder: a very, very large sunflower.Starling continued: "Because Thurston -- I’ve had the

pleasure of seeing Thurston -- does that trick with the ropes as

well. Doesn’t he? And I saw Goldin several years ago, and he

had two Hindu yoga men, as well. Is there any part of your act

--""No,

there isn’t," Carter replied briskly. "The fact of the matter

is, Colonel Starling, there are few illusions that are truly

original. It’s a matter of presentation."Starling said nothing; saying nothing often led to

gold."In

other words, I didn’t invent sugar or flour, but I bake a

mean apple pie.""So

you’re just as respected in the business for the quality of

your presentation as the magicians who actually create illusions,"

Starling said sincerely, as if looking for confirmation.Carter folded his arms, and a smile spread to his eyes, which

twinkled. "At some point this stopped being about President

Harding.""My

fault. I’m intrigued by all forms of misdirection." Starling

reached into his vest pocket, then withdrew his business card,

which he looked at for a moment before handing to Carter. "If you

think of anything else --""I’ll call you."Starling joined Griffin. They walked several steps before

Starling turned around. "Oh, Mr. Carter?""Yes?""Did

the President say anything about a secret?""A

secret? What sort of secret?""A

few people told us that in his last weeks, the late President asked

them . . ." Starling opened a notepad, and read, "‘What would

you do if you knew an awful secret?’"Carter blinked. His eyes flashed in excitement. "How dramatic.

What on earth could that be?""We’ll find out. Thank you."Carter watched them walk all the way down the stairs to their

cab, which had waited for them. A half mile away, the pelican above

the lake had been joined by a half dozen others. The day was

turning out calm and fair, giving Carter a perfect excuse to visit

his friend Borax, or to stroll in the park, or to take coffee and

dessert at one of the Italian cafés downtown. For now, he

watched the Secret Service agents depart, their cab lurching down

Grand Avenue in traffic. There were a dozen houses under

construction in Adams Point, and so Carter watched the cab

alongside panel trucks owned by carpenters and plumbers and

bricklayers until it turned a corner and vanished.And

then he tore Starling’s card into pieces and scattered them

across the stairs.With

age, the world falls into two camps: those who have seen much of

the world, and those who have seen too much. Charles Carter was a

young man, just thirty-five, but at some point after his

wife’s death, he had seen too much. Every six months or so he

tried to retire, a futile gesture, as he knew nothing except how to

be a magician. But a magician who has lost the spark of life is not

a careful magician, and is not a magician for long. Ledocq had

chastised him so often Carter could do the lectures himself,

including digressions in French and Yiddish. "Make a commitment,

Charlie. Go with life or go with death, but quit the kvetching.

Don’t keep us all in suspense."Sometimes, Carter walked in the military cemetery in the

Presidio. After the Spanish-American War, if a soldier were a

suicide, his tombstone was engraved with an angel whose face was

tucked under his left wing. But in less enlightened times, there

was no headstone: suicides were simply buried face-down.Six

nights a week, sometimes twice a night, Carter gave the illusion of

cheating death. The great irony, in his eyes, was that he did not

wish to cheat it. He spent the occasional hour imagining himself

face-down for eternity. Since the war, he had learned how to

recognize a whole class of comrades, men who had seen too much:

even at parties, they had a certain hollowing around the eyes, as

if a glance in the mirror would show them only a fool having a good

time. The most telling trait was the attempted smile, a smile aware

of being borrowed.An

hour before the final Curran Theatre show, he had been supervising

the final placement of the props, smiling his half smile when

called upon to be friendly. Suddenly a retinue of Secret Service

agents appeared, all exceptionally clean-looking young men in a

uniform Carter committed to memory: deep blue wool jackets, black

trousers, and highly polished shoes, a human shell around President

Harding.The

President was still beloved by most of the country. Word had only

just begun to trickle down from Washington that the administration

was in trouble. Harding had made no secret of his intent to hire

people whom he liked. And he liked people who flattered him. He

innocently told the Washington press corps, "I’m glad

I’m not a woman. I’d always be pregnant, for I cannot

say no."Though significantly overweight, with a high stomach that

seemed to pressure his breastbone, Harding was still an impressive

man, olive-skinned and with wiry grey hair, caterpillar eyebrows,

and the sculpted nose of a Roman senator. Yet in a glance, shrewd

men noted his legendary weak nature: his several chins, too-wet

mouth, and his gentle, eager eyes. More than one person who saw him

during his last week on earth commented on his apparent

deterioration. Even if they did not know of the extraordinary

pressure he was under, they could see it reflected in his

slack-skinned complexion.Carter, who frequently had to size up a man in an instant, saw

something more dismal. He remembered an unfortunate creature

he’d seen in New Zealand: a parrot that had evolved with no

natural enemies. Happy, colorful, it had lost the ability to fly

and instead walked on the ground, fat and waddling slowly, with no

sense that anyone could mean it ill. When humans arrived and shot

into a flock of them, the survivors would stand still, confused and

trusting that a mistake had been made, actually letting people pick

them up and dash their brains out against the ground.Harding approached Carter with his right hand extended. "I am

so very, very pleased to meet you, sir.""Mr.

President." When they shook hands, Harding jumped back shocked: he

now held a bouquet of tuberoses."For

Mrs. Harding," Carter said softly.Harding looked around, as if checking with his company to see

whether it was dignified to show delight. Then he cried, "Yes,

these are the Duchess’s favorites. Wonderful! You’re

quite good. Isn’t he good?"They

were a standard gift from Carter to potentates, fresh flowers --

from his own garden, if possible, and in midsummer, his tuberoses

were beautiful and fragrant."Now," said Harding, "I’m supposed to talk with you

man-to-man about my perhaps going onstage tonight. I have an

idea.""Yes?""You

might not know this, but when I was a boy, I did a lot of magic

tricks.""No!""Let

me tell you a couple I know pretty well," the President said

slyly.Carter fixed a smile on his face. While Harding spoke, he

focused on his ability to hold his breath and listen to his own

heartbeat. As soon as Harding finished, Carter said, "Let us think

about that."Harding leaned in close, whispering. "I understand you have an

elephant tonight. Do you think I could see him?"Carter hesitated. "I can take you. But not your aides.

She’s in a small space, and a crowd would frighten

her."Harding turned to a pair of Secret Service agents, who shook

their heads -- no, they would not let him out of their sight.

Harding’s lower lip went out. "There, you see, Carter? So

much for being a great man." He wagged his finger at the agents.

"Now, listen here, I’m going to see the elephant. Take me to

him, Carter."Puffed up like he’d negotiated a tariff, Harding passed

through a curtain Carter pulled back. The two men walked side by

side down a narrow corridor toward the rear wall of the backstage

area.They

passed the solitary figure of Ledocq, who nodded politely at

Harding, and made sure Carter saw him tapping on his watch. "Not

much time, Charlie.""Thank you.""You

have your wallet?"Carter touched his trouser pocket. "Yes.""Good. Always take your wallet onstage."Harding produced a hearty chuckle. He seemed uncomfortable with

silence, so, as he and Carter continued walking, he admitted he had

never seen an elephant up close, though at his recent trip to

Yellowstone, he had hand-fed gingersnaps to a black bear and her

cub. He was elaborating on his poorly scheduled trip to a llama

farm when Carter drew back a tall velvet curtain."My

God." They were in a small but high-ceilinged area closed off from

the rest of the theatre with screens and soundproofing. There were

two cages: one for the elephant, one for the lion. There were no

handlers. The animals were quite alone. The elephant, eating hay,

stomped twice on the floor when she saw Carter, who rubbed her

trunk in response. She was wearing a jeweled headdress and sequins

glittered by her eyes in the half-light. Harding cast but a brief

glance at Baby, the lion, before approaching the elephant’s

cage. "Is it safe?""Oh

yes. Here." Carter handed the President a peanut. With

deliberation, Harding showed the peanut to the elephant, who took

it with her trunk and put it into her mouth."It

tickled when she touched my palm. Do you have more

peanuts?"Carter handed Harding a whole bag, which Harding had to keep

away from the elephant’s probing trunk."What is her name?""I

call her Tug.""I

like her. She’s very quiet. You always think of elephants

trumpeting and stampeding and so forth. But you don’t act

naughty, do you, Tug?" Harding touched Tug’s trunk as it

found more peanuts. "Do you always need to keep her chained

up?""Luckily, no. Tug lives on a farm about a hundred miles south.

When we go on tour, she is cramped up, but not much more so than

the rest of us."Harding brought his eye near Tug’s, so they could look at

each other. "I wish she could always be on her farm.""Have you met Baby?"Harding shrugged. "Not much of a cat man. Allergic, you know. I

have a dog.""Of

course. Laddie Boy."Harding beamed, looking surprised. "You know him?" Then his

face fell. "How foolish of me. Mr. Carter, for a moment I forgot I

was President." He fell silent, and directed himself to feeding the

rest of the bag of peanuts to Tug. When he spoke again, it was to

mutter, "I’ve been counting dogs these last few minutes.

I’ve owned many dogs. People are so cruel to dogs,

aren’t they? When I was a lad, I had Jumbo, who was a great

big Irish setter. He was poisoned. And then Hub, a pug. Someone

poisoned him, I’m sure it was the boy next door, who never

liked him. Laddie Boy is lucky, if anyone poisoned him, it would be

national headlines. Quite a scandal." Tug’s trunk ran against

his hands, which he held forth, palms out. "Sorry, sweetheart, all

gone. You’ve eaten all the peanuts.""Mr.

President, we should discuss what part of the act you might appear

in.""Mmm? I was just thinking how tremendous it would be to have a

pet elephant. It would be like a dream, wouldn’t it? If I had

an elephant, I would walk him down to the shops on F Street, and,

Lord, imagine the expression on the grocer’s face when the

Duchess went for her produce!" Harding tilted his head toward the

rafters. Even in the dimness, his face looked ravaged. "A pet

elephant!" He smiled as if cheerful, and in that moment, Carter saw

that the President of the United States had that awful, borrowed

smile of a man who has seen too much."Mr.

President --""I

have a sister in Burma. She’s a missionary. One of the

natives had an elephant who was old and dying. He tried to run off

and die alone. I think the keeper couldn’t bear that, so he

put his elephant in a cage. As long as the elephant could see his

keeper by his side, he was calm, but if he left even for a moment,

he became distraught. And when the elephant’s eyesight

failed, he would feel for the keeper with his trunk. That’s

how he finally died, you know, with his trunk wrapped around his

best friend’s hand."Harding stood away from the cage, turning his back and bringing

his big hands over his face. His shoulders quaked, and the

floorboards creaked as he shifted his weight. Carter was aware of

motorcars passing outside, people laughing over dinner, bankers and

factory workers and phone operators and ditchdiggers and chorus

girls and attorneys speeding right now through their lives, gay and

so very far beyond the four walls of this soundproof

stage.Harding faced him. He sniffed, bringing his voice under

control. "Carter, if you knew of a great and terrible secret, would

you for the good of the country expose it or bury it?"Carter could see dire need in Harding’s face. It lit him

up like electricity. As was Carter’s way since Sarah had

died, he withdrew. He looked at his sleeve, inspecting his jacket

for flaws. "I don’t know if I’m qualified to answer

such a question.""Please just tell me what to do."He

brought his stage voice into play. It was like a stiff arm holding

Harding at a careful distance. "You are asking a professional

magician. One of my oaths is to never reveal a secret.

Intellectually --""Oh,

hang ‘intellectually.’ This is not a secret like how a

trick works. It is concealed to harm, not to entertain.""Then perhaps you already know the answer, Mr.

President."Harding put both hands to his face and moaned through them. "I

wish this trip were over. I wish I weren’t so burdened by

this all. I wish, I wish . . ."And

here, for Carter, the ice cracked. Behind his sangfroid voice, he

had the soul of someone who truly wanted to help. He had a glimmer

of how he might best serve the President. He said, slowly, "I know

of a way you might take your mind off this problem. Do you know of

the Grand Guignol theatre in France?"Harding shook his head, face buried in his fleshy

hands."In

any case, I know which part of my act you might enjoy the most."

Carter smiled his half-smile. "It involves being butchered with

knives and eaten by a wild animal."Harding let his hands down a little, and peeked his face around

them. It was very quiet for just a moment, and then the two men,

president and magician, began a discussion. As time was short, they

couldn’t speak at length, but they did manage to speak in

depth.Harding’s body lay in its closed casket in the lobby of

the Palace Hotel on Friday, August third. There was some

embarrassment at first, as the only American flag anyone could find

to drape over it was the one that had flown in front of the Palace

since 1913, and weathering and soot made it a shabby tribute

indeed. Eventually, a new flag was found, and wreaths from local,

national, and world leaders began to arrive, and by dusk, the lobby

was overflowing with floral arrangements, so the hotel had to start

stacking them outside the front door. By the next morning, there

were flowers, singly, or in bouquets, or in expensive vases lining

the entire block. It was said that to breathe deeply by the Palace

Hotel was to smell heaven, and for several weeks in downtown San

Francisco, when foggy, the faint, sweet aroma of roses came in

hints, then vanished.The

train that had carried Harding through his now abandoned Voyage of

Understanding was converted to a funeral train. Black bunting

draped down the sides of the locomotive and the three cars. The

casket was placed just above the level of the windows so all of the

pedestrians who stood by the platform at Third and Townsend could

take off their hats and have a final moment with Harding’s

remains.Soon, Harding would become the most reviled of American

politicians, his name synonymous with the worst kind of fraud and

egotism, but for now, as the train left the platform, boys ran

after it, trying to touch the side panels, to tag the Presidential

Seal, to get a souvenir of his passing.The

plan had been to fly across the rails at full speed, to arrive in

Washington, D.C., for official mourning, then to have the remains

interred in Marion, Ohio, Harding’s birthplace. But even

before the train reached the city limits of San Francisco, it

became apparent that America would not let him go so fast. Crowds

lined the tracks, holding candles, calling out to the Widow

Harding, singing "Nearer My God to Thee," and the Duchess ordered

the train to slow down so everyone might see the coffin, touch the

train, wave to her, so she might hear the hymn again and

again.As

news of the train spread around the country, families who lived far

from the tracks drove all night in all weather to reach them, so

they, too, could watch it passing. An eighty-six-year-old man in

Illinois told everyone he knew that five presidents had died since

he was born, and this was his last chance to see such a

thing.Soon

boys began putting wheatback pennies on the tracks, retrieving

shiny flattened ellipses once the train had passed over them.

Someone discovered that putting two tenpenny nails in an X would

fuse them together like a Spanish cross, and word spread by

telephone and radio and telegraph, and in every town, while farmers

changed into their Sunday best, and miners scrubbed their faces and

washed their hair, and church choirs lined up on either side of the

tracks and rehearsed "Nearer My God to Thee," hardware store owners

ran barrels of their nails to the tracks, to make more

crosses.But

before the train had even left California, it traveled through

Carmel, where it crossed a railway trestle over the Borges Gorge.

The engineer blew the whistle, and on a hilltop not so far away,

Tug the elephant answered briefly before returning to search her

favorite eucalyptus tree for celery and oranges and other treats

Carter had hidden there.Excerpted from CARTER BEATS THE DEVIL © Copyright 2001 by

Glen David Gold. Reprinted with permission by Hyperion. All rights

reserved.

Carter Beats the Devil

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 496 pages

- Publisher: Hyperion

- ISBN-10: 0786886323

- ISBN-13: 9780786886326