Excerpt

Excerpt

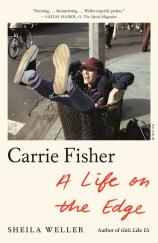

Carrie Fisher: A Life on the Edge

INTRODUCTION

FAMOUS FOR SIMPLY BEING HERSELF

On December 23, 2016—right before her favorite holiday (for a long time, she had a year-round Christmas tree in her house)—as the day was just starting in London, Carrie Fisher boarded United Flight 935 at Heathrow Airport. The plane was scheduled to leave London at 9:20 a.m. and arrive in L.A. at 12:40 p.m. (local times). With Fisher was her constant companion, Gary, the baby French bulldog she’d adopted from a New York shelter a few years earlier. She took Gary everywhere: to talk shows (interviewers happily gave him his own director’s chair), to restaurant dinners, and now to his own seat in the first-class cabin of this plane. The damaged, not-very-housebroken mutt, whose hot-pink tongue invariably hung sideways out of his mouth (“It matches my sweater,” she once told an interviewer, pointing to her own hot-pink top), was like her canine twin. They were sweet survivors together: he, of a puppyhood of neglect; she, of several things. First, she’d survived a Hollywood childhood of glamour, popping flashbulbs, and headline-making scandal when the marriage of her parents, Hollywood’s sweethearts Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher, blew apart under the spell of the gorgeous, just-widowed Elizabeth Taylor, with whom Eddie fell in love. Then Fisher survived early, sudden, international mega-fame—at age twenty, in 1977—as Princess Leia, the arch-voiced galaxy-far-away heroine in that flowing white gown and those funny hair buns. Despite Leia’s storybook royalty; her silky, almost-parody-of-feminine clothing; and a touching, repeated plea—“Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi, you’re my only hope”—made all the more plaintive because she uttered it as a hologram miniature, she was the fiercest hero of them all: ironic, tart, yet positive, and already a Resistance leader who could deal with her own survival while her twin brother, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), was still a mere farm boy and her later love Han Solo (Harrison Ford) was a cynical gun for hire. She was the only girl warrior among the boys, and she could hold her own better than they could. If second-wave feminism had a science fiction stand-in, it was the Princess Leia created by Carrie Fisher.

As Fisher and Gary settled into their plane seats for the long flight home to Los Angeles, if Fisher had wanted to use the hours in the sky to mull her accomplishments, she had plenty about which to feel satisfied.

More seriously than surviving huge early fame, Fisher was a survivor of inherited drug addiction and of major bipolar disorder—the latter an incurable, biologically rooted mental illness that causes changes in the way one’s brain processes the chemicals the body naturally produces. Fisher’s version—the more serious bipolar one versus bipolar two—could come on unpredictably, and for her, enduring it was like living “with a war story.” She talked about both of these problems so frankly and so helpfully to others that in the early years of the twenty-first century “she completely kicked the stigma of bipolar disorder to the curb,” says Joanne Doan, the editor of bp Magazine. Expert after expert would gratefully agree: nobody took the shame out of bipolar disorder the way Carrie Fisher did.

Of course there was more, much more. Fisher had a brilliant, sage honesty and madcap personality—a crazy joyousness—pretty much unequaled in Hollywood. During the three-year run of her self-written one-woman show Wishful Drinking—her autobiographical late-career tour de force—she started sprinkling the audience, and her friends, with glitter. Actual glitter. She did it backstage at the Oscars; she did it at restaurants. She became such a glitter aficionado she had special glitter-holding pockets sewn into her coat. Many years earlier, on her honeymoon with Paul Simon, she’d brought the bridesmaids who traveled to the Nile with them silly fairy costumes to camp up their visits to the ancient catacombs. Her house, tastefully decorated though it was with antiques and folk art, was also chockablock with felicitousness: the tiles in the kitchen were embossed with linoleum images of Prozac bottles; one of her bathrooms contained a piano (didn’t all bathrooms have pianos?), and a series of what she called “ugly children portraits” hung over her bed.

Her bons mots were epic. During an Equal Rights Amendment march in the 1980s with her friend the screenwriter Patricia Resnick, Fisher had wisecracked of a small weight gain, “I’m carrying water for Whitney Houston.” When she first dated Paul Simon—who was almost as short as her five feet one—she’d remarked, “Don’t stand next to me at a party. They’ll think we’re salt and pepper shakers.” When, with her fluent French, she had saved her friend, the world-famous security expert Gavin de Becker, from the Hotel George V concierge’s outrage because Gavin had made off with the bathrobe from his room, she eyed the straight-arrow boy she’d known in high school and said, “I didn’t know you were a thief.” Pause. “Now that I do, I’ll take you traveling with me more often.” When, late in the first decade of the twenty-first century, men started weight and age shaming her on social media, she bounced back with “You’ve just hurt one of my three feelings.” When her father, Eddie Fisher, wrote of his dislike for her mother, Debbie Reynolds, in his second memoir and falsely accused Debbie of being a lesbian, Carrie, hurt and angry, nevertheless riposted, “My mother is not a lesbian.” Pause. “She’s just a really, really bad heterosexual.” Most recently, when, six weeks before she boarded this plane, it was revealed that the presidential candidate Donald Trump, whom she despised, ogled only beautiful women, she tweeted, “Finally, a good reason to want to be ugly.”

It wasn’t just snappy wisecracks that were her forte; she was good at substantive aphorisms. She knew from the up-and-down (including the very down) career moments of her parents that “celebrity is just obscurity biding its time.” And she warned about the toxic nature of competitive Hollywood. “Resentment,” she liked to say, “is like drinking poison and waiting for the other person to die.” Fisher’s main maxim for her complicated life was “If my life wasn’t funny it would just be true, and that is unacceptable.” It had to be funny, and she made it so.

Fisher was gifted with a quicksilver tongue. “She is the smartest person I know,” many of her friends said about her. “Charisma” is an easy word to throw around, but she possessed it. In her book The Princess Diarist, she wrote that as a girl she had longed “to be so wildly popular” that she could “explode on your night sky like fireworks at midnight on New Year’s Eve in Hong Kong.” Many would say that Carrie Fisher had achieved this goal. She was “irresistible,” said Albert Brooks; her friend Richard Dreyfuss called her a subject of “worship” among their friends. “I am a very good friend,” she once told Charlie Rose, in a way that didn’t sound conceited, because she’d been brutally frank about so much else. She was a “loyal, alert, fierce, vulnerable friend,” she’d said. “I can go the distance with people.”

“Vulnerable?” Charlie Rose asked, beaming at her easy wit. “Everyone told me I would love you.”

“Unfortunately, yes,” she’d answered, adding, with tart self-knowledge, “I can do wrong better than anyone.”

The night before she’d boarded the plane for L.A., she’d had dinner with another one of her best friends, the author Salman Rushdie, and Fisher’s newer and younger friend, the Irish actress and producer Sharon Horgan, whose wacky-bitchy mother-in-law she played on the TV series Catastrophe. She and Sharon and their co-star Rob Delaney (who played Sharon’s husband) had just filmed one of the final episodes of the third season of their jubilantly profane comedy about a hapless marriage.

The three—Rushdie, Horgan, and Fisher—had had a good restaurant dinner, full of laughter, while Gary the dog farted, Horgan recalled. Says Rushdie, who’d had a twenty-year friendship with Fisher and cared deeply for her (and sometimes worried about her, as did many of her friends), “She seemed hale and healthy, and she ate heartily. She’d bought a house in Chelsea, which seemed to lift her spirits.” Fisher, a gift giver of wit and thoughtful specificity (and an opinionated matchmaker of Rushdie with women), handed the writer a tiny chocolatier’s box over the dinner table. He opened it, and “there were a pair of … chocolate tits!” He laughed, of course, and vowed to devour the luscious breasts slowly over the following nights. (He never would; they’re still in his freezer.) Fisher gave Horgan a lovely antique pin. No one gave presents like Carrie Fisher.

After the dinner, Fisher returned to her hotel for a good night’s sleep before her flight. She had packed a lot into the previous two months: she’d filmed her part in a glamorous sci-fi movie called Wonderwell in Italy and zipped over to London to shoot several episodes of Catastrophe while buying the house in Chelsea. She’d also flown to L.A. and back for a few-weeks-late sixtieth birthday party that her mother, Debbie, had insisted be a big deal, including inviting Brownie and Girl Scout troop alumnae as well as all of Fisher’s close celebrity friends. Fisher worried deeply about her eighty-four-year-old mother’s health; Debbie had suffered two strokes in 2016. But Reynolds was, like her famous movie character, unsinkable: insistent on never slowing down. This workaholism had been passed on to her daughter.

The weeks before, Fisher had also been busy promoting The Princess Diarist, which disclosed the secret affair she’d had with Harrison Ford while filming the first Star Wars and the intense vulnerability she had felt at nineteen. It was her seventh book and, like all the others, a bestseller. She hadn’t been feeling particularly well. “She’d lost some spring in her step” during November, Sharon Horgan had noticed. In fact, she was almost ill enough to cancel a TV show hosted by one of her many English best friends, Graham Norton, to promote the book, but she had decided—just as her mother would have—that the show had to go on, so she went through with it.

* * *

The plane took off, arched over the Atlantic Ocean, nipped the lower tip of Greenland, entered Canada, and zoomed over Montana, Idaho, and Nevada, approaching California.

During the eleven-hour flight, two young performers, a comedian named Brad Gage and his girlfriend, the YouTube personality Anna Akana, happened to be seated near Fisher and Gary. Huge fans (Anna had just read The Princess Diarist), they were amazed at their luck. Fisher slept for much of the flight, but as the plane began descending toward LAX, at thirty thousand feet, she woke abruptly and started violently throwing up. She said she couldn’t breathe. For decades, she had worried about sleep apnea—a serious sleeping disorder where breathing can stop, dangerously. Now here it was.

Passengers who were nurses rushed to her side and administered CPR.

“Don’t know how to process it but Carrie Fisher stopped breathing on the flight home,” Akana tweeted. “Hope she’s gonna be OK.” Akana has a large Twitter following. This was the first news anyone, even Fisher’s family, heard about the emergency. “I’m in complete shock,” Gage tweeted, backing up the account.

Not long before the scheduled landing, Fisher went into severe cardiac arrest. The pilot radioed and “coordinated [for] medical personnel” to meet them at the gate. The pilot told air traffic control, “We have some passengers, nurses assisting the passenger, we have an unresponsive passenger.”

According to a log from the Los Angeles Fire Department website, documenting real-time emergencies, at 12:11 p.m. a fire department truck full of paramedics rushed over to gate 74, waiting for the flight’s arrival. When the flight did arrive at 12:25 (two minutes before its revised and sped-up scheduled arrival), the paramedics “provided advanced life support and aggressively treated and transported the patient to the local hospital”—UCLA Medical Center’s intensive care unit.

It wasn’t long until all the major websites lit up with versions of this shocking headline: “Carrie Fisher Suffers Massive Heart Attack on Plane.”

Copyright © 2019 by Sheila Weller

Carrie Fisher: A Life on the Edge

- Genres: Biography, Nonfiction

- paperback: 432 pages

- Publisher: Picador

- ISBN-10: 1250758254

- ISBN-13: 9781250758255